The Myth of the “American Coup” in Chile

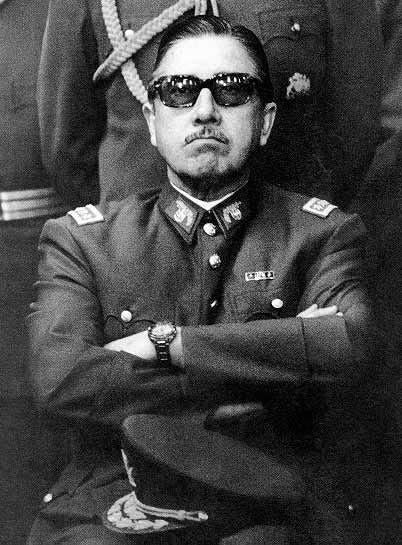

This month marks fifty years since the military coup in Chile that removed the Leftist president, Salvador Allende, and replaced his government with a military junta led by General Augusto Pinochet. Jeremy Corbyn was speaking for much of his generation and for many others on the Western Left—the global Left, come to that—when he marked the occasion by referring to a “U.S.-backed coup”. Few events of the Cold War have such resonance in the present day: for Corbyn and many others, the 1973 Chilean coup is the archetypal instance of ruthless American “imperialism” and hypocrisy, betraying professed U.S. values to support the brutal overthrow of an idealistic, democratically-elected leader. It is perhaps unsurprising that a belief so central to Corbyn’s being has such a tenuous relationship with reality.

THE 1970 ELECTION IN CHILE

Chile had been theoretically democratic since the 1830s, shortly after its foundations, and progressively became more so in practice. After a political collapse in 1891 and a series of military rulers in the 1920s and 1930s, Chile had been set on a course of stability and representative politics that eluded many of its neighbours. This “exceptionalism”, specifically the military’s non-intervention in politics, was a source of pride to Chileans. What began the strain in Chilean politics was the establishment of the Soviet bridgehead in Cuba in 1959 under Fidel Castro. Still, Chile’s representative civilian government had not been shattered, as so many in the Western Hemisphere had been by the wave of Communist subversion and the reaction to it. The conservative elite that had dominated through the 1940s and 1950s was exhausted, but the Christian Democrats who won the 1964 election—led by President Eduardo Frei Montalva (r. 1964-70)—adapted, taking a more reformist posture, including on the knottiest question of all: land reform. Though Frei was immensely popular in the country at large, his triangulation had contributed to the already worsening polarisation of the political elite by breaking his tacit alliance with the Right and taking away the issues on which the hard-Left hoped to build Revolution. The fears on each side were expressed in ever-more aggressive forms and fed on each other—a vicious cycle that eroded the traditional civility and consensus that had grounded Chilean politics. It was in this context that a radical like Salvador Allende could make such headway by 1970.

In the campaign for the 4 September 1970 Chilean elections, the CIA had provided funds and support for anti-Allende messaging—highlighting that he was a Marxist aligned with the Soviet Union and particularly Moscow’s Cuban colony—but had refrained from any more direct interference to support either of his opponents. International Telephone and Telegraph (ITT) did provide funds to Allende’s opponents, and in Leftist and Third Worldist folklore this would be taken as proof of a “banana republic” policy, with U.S. policy directed by U.S. corporations, but the operational connection between U.S. State policy and U.S. private interests was weaker in Chile than it had been in Guatemala in 1954, where CIA Director Allen Dulles owning shares in the United Fruit Company was held up as the key to all mythologies.

Allende, in contact with the KGB since the early 1950s and a Soviet asset since 1961, received the full backing that Moscow could offer in the 1970 election: lavish personal funds (Allende’s KGB case officer Svyatoslav Kuznetsov handed him $50,000 in cash at one point); at least $750,000 ($6 million in 2020s money) for Allende’s party and propaganda apparatus, sent directly from the Soviet Union and through Fidel Castro’s Cuba; and a carefully targeted bribe of $18,000 by the KGB to keep a Left-wing Senator from standing in the race, which would have split the Leftist vote. Since Allende won with 36.6% of the vote and the next-closest candidate, the Rightist independent Jorge Alessandri, received 35.3%s—a difference of about 40,000 votes—it is probable that the KGB intervention was decisive in Allende’s victory. Moscow Centre regarded the triumph of Allende (codenamed LEADER) as the greatest Communist success in Latin America, “second only” to their Cuban Revolution.

It is not anomalous that the CIA’s interference in Chile’s 1970 election is invariably cited, yet the KGB’s much more important intervention—and Allende’s deep, long-standing relationship with Soviet intelligence—is frequently omitted. No account of developing countries in the Cold War will fail to mention the activities of the CIA, but both popular perceptions and major scholarly works—on the histories of those countries and on Soviet foreign policy in the “Third World”—routinely leave out the role of the KGB entirely. A significant reason for this is that the KGB—as the lynchpin of a totalitarian system—was able to keep its actions covert, while the CIA, answerable to a democratic society increasingly obsessed with official transparency since the 1970s, has had its most sensitive secrets aired for all the world, not by an enemy service but by investigators in the U.S. government. “The result has been a curiously lopsided history of the secret Cold War in the developing world,” writes intelligence historian Christopher Andrew, “the intelligence equivalent of the sound of one hand clapping.”

The CIA, having failed in stopping Allende winning the election, now set about trying to prevent him taking office on 3 November 1970.

Since the election itself did not formally choose the president—it was up to the Chilean Congress to choose the president from among the two candidates who received the most votes—the Agency’s “Track I” was to try to have the Chilean Legislature reject Allende’s bid to become president. There was a strong norm that the Congress selected the candidate who won the elections, but the Allende situation was highly unusual: with Chile’s polarisation over the preceding decade and Allende’s obvious Soviet connections, including his frequent trips to Havana in the 1960s, there was widespread doubt Allende would adhere to the constitution. The attempt was basically, as Mark Falcoff explains, for a constitutional coup to circumvent Chile’s ban on presidents serving consecutive terms: the idea was that the Congress would vote for Alessandri as president, and he would, after formally serving as president for a number of days, resign and call new elections in which the popular outgoing President Frei could stand against Allende. This failed.

It was clear even before 24 October 1970, when the Congress certified Allende’s election, that the Congressmen—including most of the Christian Democrats, a party trending considerably to the Left of where it had been and where Frei was—had accepted Allende’s pledge that he would govern according to the law. It should be said in the Chilean elite’s defence that even at this moment, when significant numbers of them were indulging the headiness surrounding Allende, sight was not lost of their constitutional duties. The pledge Allende was compelled to sign as a condition of being granted the presidency, the Statute of Democratic Guarantees, was incorporated into the constitution. It was clearly written with the Cuban example in mind; it was especially focused on preventing a Castro-style takeover of the trades unions. It bound “Allende publicly and explicitly to … the maintenance of the norms of pluralistic constitutional democracy”, and it set out—in that indirect language that is traditional of Latin American politics—the penalties for failure, insisting on the “independence” of the Armed Forces and the military’s non-interference in politics so long as the constitution was respected. The political potency of this manoeuvre would be demonstrated in due course.

At this time, however, Allende signed the Statute of Democratic Guarantees as what he called a “tactical need”, believing it was a paper promise that could be easily ignored, and the U.S. assumed the same. The CIA therefore moved to “Track II”: trying to prevent Allende taking office by force. The CIA’s desire for the Chilean military to stage a coup d’état ran into the fact that it was an institution that in its culture and identity rejected such things. That said, while neither side seriously saw their deliverance or demise as likely to come at the hands of the army through the tumult of the 1960s, there were signs that military discipline was fraying. As the Chilean military been out of politics for forty years, it did not have the sway of its counterparts in Latin America to secure large budgets for itself by the implicit threat that it would take what it wanted if the politicians did not deliver. The resentment over military pay had led to a brief—and non-violent—insurrection (El Tacnazo) in October 1969, led by General Roberto Viaux. The “Tacna Agreement” ended the disturbances within twenty-four hours: the government conceded to the main demands, upgrading the pay of army personnel and increasing the defence budget, and the military conceded the retirement of its senior leaders, Viaux included. It was as a result of this insurrection that General René Schneider was made Commander-in-Chief of the Army.

Schneider very publicly committed to keeping the military out of politics in May 1970, laying down the so-called “Schneider Doctrine”. Schneider did indeed have high-minded reasons for this, as a constitutional officer, and stuck to his position against enormous pressure: he was receiving “almost daily representations by retired officers, politicians, and businessmen begging him to ‘save the country’ either by supporting a constitutional coup or by some other means”. Schneider had more earthy motives, too: he thought the politicians had driven the country into a mess and were now trying to dodge the responsibility for it by handing everything over to the Army. “We are not so stupid” as to fall for it, Schneider told his deputy.

Thus, Schneider was the primary obstacle to the CIA’s “Track II” and his removal was the Agency’s immediate tactical goal in late 1970 after “Track I” collapsed. The CIA’s Operation FUBELT was ostensibly meant to kidnap Schneider and—in one of those too-clever-by-half Agency flourishes—blame it on Allende’s supporters. After Schneider was abducted, he would be “secretly flown to Argentina; the military would announce that he had ‘disappeared,’ blaming Allende supporters who would then be arrested; President Eduardo Frei would be forced into exile, Congress dissolved, and a new military junta installed in power.” President Richard Nixon appears to have thought Frei’s exile would be brief and the junta would invite him back to compete in elections that restored civilian rule, though Nixon’s view of what would happen after the coup was hazy and far less of a priority for him that simply having an anybody-but-Allende government in Santiago.

Viaux approached the CIA in early October 1970, telling them he was having insurrectionary thoughts again. The Agency was not impressed by Viaux—they considered him a bit “far out” and it was not very encouraging that a senior officer said he needed foreign arms to execute a coup—but the CIA was not exactly spoiled for choice in its options. American money was transferred to Viaux and his “false flaggers”, but by mid-October the U.S. had lost faith in Viaux.

Viaux was incapable of a coup and a failed attempt by him would eliminate the possibility of a successful coup in the future and risk “unfortunate repercussions, in Chile and internationally”, National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger and Thomas Karamessines, the head of the CIA’s Directorate of Operations, the Agency’s covert action wing, concluded in a meeting on 15 October 1970. The “decision to de-fuse the Viaux coup plot, at least temporarily”, in the Kissinger-Karamessines meeting was relayed to the CIA, with the instruction that “the Agency must get a message to Viaux warning him against any precipitate action”. The Agency was to “continue keeping the pressure on every Allende weak spot in sight” and Viaux was to be reassured that he was not being dropped (“Preserve your assets. We will stay in touch. … You will continue to have our support.”), but the coup plot was to be paused “until such time as new marching orders are given”.

In a telephone conversation with Nixon later on 15 October, Kissinger said: “I saw Karamessines today. That looks hopeless. I turned it off. Nothing would be worse than an abortive coup” [italics added]. Nixon replied: “Just tell him to do nothing.”

In the best traditions of the CIA, catastrophe ensued. Viaux ignored the explicit U.S. instructions to cease-and-desist; two abduction efforts against Schneider, on 19 and 20 October, failed; the third attempt, on 22 October, ended with Schneider being mortally wounded (he died on 25 October); and Allende was sworn in, riding a wave of patriotic sentiment from Chileans who, whatever they thought of Allende personally, resented the effort to derail Chile’s constitutional processes.

This fact pattern means the U.S. certainly has some culpability for Schneider’s death, but it refutes the oft-made accusation that the U.S. intentionally murdered Schneider. The only way the accusation can be kept alive is by distorting the documentary record to claim that Kissinger was lying about calling a halt to the coup attempt on 15 October and distorting the context to portray Kissinger as micro-managing the CIA operations in Chile in September-October 1970. The reality, as Falcoff describes, is quite otherwise: “during September and October 1970 … the telephone record reveals a Kissinger preoccupied with … Vietnam, a Soviet submarine base in Cuba, the [Dawson’s Field] Black September plane hijacking, Nixon’s planned visit to Europe and to the Sixth Fleet, the defense budget, and the Pugwash conference on U.S.-Soviet relations, but with Chile only slightly. Thereafter, there is nothing at all [about Chile] until June 1973, when he and Nixon discuss a failed military revolt against Allende, and then no further references until after Pinochet’s assumption of power”.

Some grist for the mill of blaming the U.S. for deliberately assassinating Schneider is provided by the CIA’s self-satisfied reaction. On 23 October, for example, after Shneider had been shot but while he was still alive, the Agency suggested all was proceeding according to its design. “[A] coup climate exists in Chile”, CIA analysis maintained, at the very moment Chileans were rallying around Schneider’s replacement as Chief of Staff, General Carlos Prats, in insisting the constitutional process play out. Another factor that sustains the accusation is the clear evidence that after Viaux’s crew were put on ice, the CIA station in Santiago continued looking for “Track II” options, and thought they had found one. When the details are examined, however, it becomes apparent that the accusation is without merit.

The more hopeful “Track II” option the CIA had alighted on was General Camilo Valenzuela, the head of the Santiago garrison. It was arranged to send “three submachine guns and some tear-gas canisters and gas masks … through the U.S. diplomatic pouch” to Chile and they were handed to intermediaries for Valenzuela at 2 a.m. on 22 October. By the time Valenzuela received the munitions, Schneider had already been shot—again, by a team acting against an express CIA instruction to stop their activities, however naïve it was to hope that such an instruction would be heeded. The Church Committee, the 1975 investigation into U.S. intelligence activities led Senators who were aggressively hostile to the CIA and the Nixon administration, underlined the point, concluding that Schneider was killed “by conspirators other than those to whom the CIA had provided weapons earlier in the day” and the guns used “were, in all probability, not those supplied by the CIA”.

The continued support the CIA promised Viaux came to nothing: he was soon arrested and played no further part in Chilean politics, being sentenced to a lengthy prison term from which he was only released after Pinochet took power. The machine guns sent to Valenzuela were “returned unused” and he also faded from the picture. Politically, Schneider’s heroic status and Prats’ firm constitutionalism had discredited Right-wing schemes, in the military and beyond, for a coup—the precise opposite of the CIA’s intentions. What would revive such thinking was the experience of Allende’s regime.

THE ALLENDE REGIME

Allende’s was a “totalitarian project”, as former President Frei called it, which has been rescued from the opprobrium that usually attaches to such projects by the fact it was terminated before completion and by the great propagandistic skill with which the myth-image of Allende’s martyrdom was cultivated by his Soviet sponsors in the years after his death.

The U.S. actions in 1970 have created confusion, some of it honest and some of it wilful, about the coup that actually did bring down Allende in 1973. Almost invariably when somebody presents a “smoking gun” of U.S. complicity in the 1973 coup, it transpires to be a document or transcript from 1970. Five days after Allende was toppled in September 1973, Kissinger said in a telephone call with Nixon, “We didn’t do it”, and that is the plain truth. The U.S. did not plan the 1973 coup and was not even aware of the plot. The most that can be said is what Kissinger added in that call: that the U.S. “created the conditions as great as possible”. In reality, even this is overstating the case. Chileans acted in 1973 for Chilean reasons in response to conditions created by Chileans, but, whether self-flagellating or boasting, American officials can struggle with the idea events occur in the world without their involvement.

The argument that the U.S. “created the conditions” for the 1973 coup centres on claims the U.S. took steps to damage the Chilean economy—and the evidence adduced consists of documents and statements from U.S. officials in 1970. Ten days after Allende’s election in 1970, Nixon was recorded saying that he would “make the economy scream”. This quotation is infamous in circles where the Chilean coup is the archetype of U.S. Imperial abuses. On 16 October, after the Viaux coup was paused but the general “Track II” policy continued, the CIA headquarters cabled the station in Santiago, “We are to continue to generate maximum pressure toward this end”. Soon after Allende took office in November 1970, Nixon determined that the U.S.’s “public posture” would be “correct but cool, to avoid giving the Allende government a basis on which to rally domestic and international support for consolidation of the regime”, and in the background the U.S. would “seek to maximize pressures on the Allende government to prevent its consolidation and limit its ability to implement policies contrary to U.S. and hemisphere interests.”

This all sounds minatory, but the rhetoric far outstripped the policy. For instance, Nixon wanted to “bring maximum feasible influence to bear in international financial institutions to limit credit or other financing assistance to Chile”. As it turned out, the maximum feasible influence was not much: Chile under Allende received over $100 million ($800 million in today’s money) from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

“The documentary evidence is … unambiguous”, Falcoff summarises, “the most serious charge that can be levied against the Nixon administration is that it contemplated economic sanctions against Chile at a time when Allende had yet to lay a hand on American investments in the country and was still making payments on Chile’s debts. But even that envisaged policy was never truly implemented.” As just a few examples: in July 1971, Allende expropriated American copper holdings and the Hickenlooper Amendment was not invoked; Chile defaulted on its debts to the U.S. in November 1971, but it did not stop agreed loans being sent; humanitarian aid was never cut off; and U.S. aid to the Chilean military tripled from 1970-73, which considerably assisted Allende in consolidating his regime by relieving pressure on the civilian budget and drawing the military leadership, Prats in particular, closer to being co-opted by the president.

The economic ruin that afflicted Chile by 1973 was a result of Allende’s policies, not U.S. sanctions. Allende came into office at the head of Unidad Popular, a “popular front” coalition that had the Soviets’ “fraternal” Communist Party as one of its leading elements and contained the Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR), a terrorist-revolutionary outfit devoted to Lenin’s example, one of whose leaders was Allende’s nephew. “Our aim in Marxist socialism, total and scientific”, Allende told a stenographer in 1971, and to that end the paramilitary squads of the parties in his coalition directed the revolutionary workers’ committees (cordones industriales) in often-violent seizures of factories and farms across the country, inevitably bringing the enterprises to a near-halt, collapsing productivity, wages, and foreign investment, while creating a food shortage. The constant harassing of small businesses and other operators made goods Chileans had taken for granted unavailable—not that most people could have easily afforded them by late 1972. The unchecked printing of currency sent inflation through the roof: inflation hit nearly 80% in 1972, reached 350% by 1973, and stood at over 1,000% by August 1973. Chilean truckers went on strike in October 1972, infuriated at the extortionate freight rates they were being charged when they could not even access spare parts, and the strike spread to other sectors, notably shopkeepers, with threats that engineers, doctors, and other professionals would join in. Allende’s effort to dismantle or co-opt the independent trades unions was shown to be seriously incomplete, and the whole economy was virtually paralysed.

The economic disaster was accompanied by escalating political repression. The Soviets maintained regular contact with Allende once he was in power, notably doing this through his old KGB handler Kuznetsov, not the Soviet ambassador. Allende was officially a Soviet confidential contact, not an agent, but he was regularly paid by the Soviets—in just October 1971, he was given $30,000—and Allende did as directed by Moscow. (The details of Allende’s subordination to Moscow were revealed in the Mitrokhin Archive after the Cold War was over, but it was hardly a secret in real-time: Allende identified the Soviet Union as Chile’s “Big Brother” in a speech to the Kremlin in December 1972 and publicly said his views were “identical” to those of the Soviet Communist leaders.) The KGB’s consistent advice was for Allende to rely more heavily on the security apparatus in governing, to bring Soviet “advisers” into the military-intelligence system, and to tighten Chile’s links with Castro’s Cuba. Allende accepted all of these things. It was black-beret Cuban troops and Cuban-trained militiamen from Allende’s Socialist Party (PS) that formed the Praetorian Guards, the “Group of Personal Friends” (GAP or Grupo de Amigos Personales), for Allende and his family.

Revolutionary mobs, sometimes in the form of Communist-led trades unions, were unleashed on businesses and universities where anti-Allende sentiment was strong. Using the cover of nationalisation, Allende moved to bring the non-Marxist radio stations and newspapers under State control by eliminating the sources of funding for the independent media. The U.S. continued a flow of money, amounting to at least $6 million (nearly $50 million today), to opposition parties and the press. Those so inclined will take this as proof of the indictment that the U.S. was behind the destabilisation of Allende’s government, but the reality is it helped keep some semblance of Chilean pluralism operating.

The Soviets pushed Allende during his entire reign to implement more repression and Allende obliged them, though the Centre never thought it was enough. In reorganising the intelligence services, particularly the Servicio de Investigaciones secret police, Allende told his Soviet handler in February 1973 he was “very much counting on Soviet assistance”. The Soviets helped the Servicio acquire the capabilities to intimidate Allende’s enemies and it “gained a reputation for turning the cellars at its headquarters into torture chambers”. The factional disputes for control of the Servicio, however, between PS cadres and the Communists, damaged its efficacy as an intelligence-gathering agency. Allende’s efforts to infiltrate the military and purge “reactionary” elements if anything provoked the outcome it was supposed to forestall. The Soviets had been pessimistic about Allende’s prospects for survival since 1972—the truckers’ strike had been an alarming display of opposition—and in the spring of 1973, during a visit to the First Chief Directorate (FCD) headquarters at Yasenevo, the KGB chief Yuri Andropov said he was sure Allende was doomed. The Centre saw this as self-inflicted, because of Allende’s chronic economic mismanagement and his failure to transform Chile into a totalitarian State fast enough; the after-action reports would particularly blame the latter aspect for Allende’s downfall.

The Leftward-trending Christian Democrats had been intoxicated by Allende’s victory and tried to cooperate with him. On the one hand, the devastation of the country had discredited the Christian Democrat leaders who had pushed this course, and on the other hand, the party had been subjected to relentless political warfare from Allende, trying to create a schism and if possible collapse to eliminate one of the major remaining loci of independent political power. At the parliamentary elections of March 1973, the Christian Democrats did the unthinkable and went into coalition with the conservative National Party; this alliance won 87 seats (58%). The Allende coalition lost its majority, slipping to 63 seats (42%).

Emboldened by their electoral boost, the democratic opposition made a last-ditch effort to rein-in Allende through constitutional mechanisms. It proved hopeless: the mechanisms had been eroded too far, and Allende’s ruling clique, instead of retrenching after a democratic rebuke, became more overt in its extremism after the spring of 1973. Oscar Waiss, an intimate friend of Allende’s, the director of the government gazette (Diario Oficial), bluntly confessed in exile a few years later: “The moment had come to throw away all legalistic fetishism”. Allende tried, said Waiss, to make a clean sweep of the military leadership, the Supreme Court, the broader Judiciary, independent political offices, and the media—“the whole pack of counterrevolutionary journalistic hounds”, as he put it. It was in reaction to this brazen totalitarianizing process that by the summer of 1973, Allende’s government was declared an outlaw by the other branches of the State.

Allende had ceased recognising checks on his authority and was ruling in an autocratic, arbitrary manner using decrees. The Chilean Supreme Court had protested this practice numerous times through 1972, documenting Allende’s serial defiance of the law, both in refusing to implement judicial rulings he did not like (often to protect criminals who were political allies) and actively ordering illegal actions (such as the violent seizure of private property). In late May 1973, the Supreme Court issued an official statement noting that Allende’s “decided obstinacy in rebelling against” the law had moved Chile from a “crisis of state under the rule of Law” to a “breakdown of the legal order”. Allende tried to refute this, but the Supreme Court issued a second ruling on 25 June 1973 that simply said Allende had obliterated the separation of powers, subordinating the Judiciary to the Executive.

Less than two weeks later, on 8 July 1973, Eduardo Frei, the president of the Senate since the March elections, Luis Pareto, the president of the Chamber of Deputies, issued a joint declaration saying that under the “ideological … scheme that the nation’s majority rejects”, Chile had been brought to “the worst political, economic, social, and moral crisis that its history has known”, where “neither the laws nor institutions are respected and have been mocked openly”.

Frei’s leading role in rescuing Chile from going the way of Cuba was “as unpredictable as it was extraordinary”, José Piñera explains. Critics had lambasted Frei as the “Chilean Kerensky”. Frei had courted the Left, spent his life avoiding the label “anti-Communist”, and his last term as President had in so many ways prepared the ground for Allende. When the moment came, however, Frei was nothing like Kerensky: he recognised where the danger came from, was willing to make common cause with conservatives and the military to prevent it, and stayed in his country to lead the resistance to socialist totalitarianism, knowing the immense risk to his life, a risk concretised no later than June 1971 when Leftist terrorists assassinated his political heir, Edmundo Perez.

The Chilean predicament—deprived of constitutional remedies by a widely detested, Soviet-dependent socialist despotism that had used democratic means to take power then plunged the country into a chaotic maelstrom of economic collapse and political violence—led to comparisons with 1930s Spain. Many Chileans believed the country was on the brink of civil war. This prospect was not a deterrent to Allende and his lieutenants. The Foreign Minister, Socialist Party ideologue Clodomiro Almeyda, had raised the Spanish spectre before Allende took office—and meant it positively, as the route by which the Revolution would succeed in Chile. Almeyda’s specific historical analogy was inapposite—the Nationalist rebellion had, after all, prevailed over the Bolshevized Spanish Republic—but the socialist belief that civil war offered a revolutionary short-cut was entrenched because that is what Lenin did. Allende had been strongly influenced in thinking along these lines by Castro, who could claim to have followed Lenin’s winning formula, according to Chilean historian Claudio Veliz, a personal friend of Allende’s. Castro’s last letter to Allende in late July 1973 contained advice on how to win the impending civil war and promises of Cuban help.

Avoiding civil war was a core intention of the Chamber of Deputies resolution issued on 22 August 1973, passed by 81 votes to 47, which was the crucial event in setting the stage for the military coup. The resolution declared that the Allende government had abolished the “Law-Abiding State”, annexing to itself the powers of the Judiciary and the Legislature; violated the Statute of Democratic Guarantees, adherence to which was the condition for accepting Allende as president; engaged in systematic human rights abuses, including using illegal militias to terrorise citizens and suppress their rights of expression; and aimed to refashion the country into a Marxist totalitarian system. The resolution went on to remind the ministers overseeing military institutions, many of whom were military officers, that their loyalty was to the constitution not the current president, and directed them to request that the Chilean Armed Forces put “an immediate end” to the official lawlessness that had overtaken Chile.

Everyone understood what this meant. On 24 August, Allende released a letter to the nation saying that what the parliament had done “is ask for a coup d’état”. Piñera notes that Allende was quite correct—and entirely to blame. It was Allende who had wilfully removed juridical options in Chile, and he would now face the consequences.

THE ENDGAME

When Kissinger met Ambassador Nathaniel Davis on 8 September 1973 and Davis said, “the odds are in favour of a coup, though I can’t give you any time frame”, he was expressing the conventional wisdom known to any child in Chile at that time. What is clear is that Davis, nor any other U.S. official, knew any specifics of what was coming in Chile. If the notion of Kissinger micromanaging CIA operations in Chile in September-October 1970 is a misrepresentation, it is an outright lie about September 1973, when Kissinger was inter alia managing Vietnam after the fake “peace” agreement, dealing with a mounting Middle East crisis that would become the Yom Kippur War, and preparing for his own Congressional confirmation hearings as Secretary of State. Kissinger begins the conversation with Davis by saying, “Tell me how things are going in Chile”, and it is clear from the transcript Kissinger really knows little beyond the broad outlines. Davis tells him events are moving quickly and he had given “firm instructions to everybody on the staff … that we are not to involve ourselves in any way”: “Our biggest problem is to keep from getting caught in the middle.”

Even the Church Committee, which tried to put the darkest possible spin on the CIA’s actions in 1973, conceded flatly that the “CIA did not instigate the coup that ended Allende’s government”. The most the Committee could do was say the Agency “was aware of coup-plotting by the military”—which was not classified information: the gossip on the streets of Santiago spoke of nothing else for months before September—and by not sending a forceful, explicit signal of discouragement, the Agency had “probably appeared” to give approval.

There had been a warning shot for Allende on 29 June 1973, when the extreme-Right Patria y Libertad movement had gathered a small cabal of soldiers to launch a coup attempt. The Soviets had discovered the plot and helped Allende organise the swift crushing of the uprising, which looked good in the KGB reports to the Centre, but was not all that impressive. The operational security of the plotters was abysmal and the whole episode was vaguely farcical; the tanks driving towards the presidential compound stopped at the traffic lights. What was noticed by General Pinochet, an apparent Allende loyalist who had become Commander-in-Chief of the Army when Prats resigned the day after the Chamber of Deputies resolution, was that Allende’s radio appeal for “the people” to “pour into the centre of the city” to defend the Workers’ State had fallen flat; there was no popular will to defend Allende’s government. A further important element of Allende’s radio address was that it was his first public admission that he had Left-wing paramilitary groups at his disposal. The context of the admission—the coup attempt—was somewhat lost. As Frei recalled later, it had long been an open secret that “the Marxists, with the knowledge and approval of Salvador Allende, had brought into Chile innumerable arsenals of weapons”, and what many heard in Allende’s public reference was a threat to use them to stay in power.

Allende’s incompetence was not selective; it extended even to his personal safety. Despite the June putsch warning, the ubiquitous rumours in Santiago of coup plots after that, and the KGB’s repeated, direct warnings to Allende of military conspiracies against him, he did nothing to shore-up his position. When Pinochet and the other officers initiated their coup against Allende on 11 September 1973, Allende had about sixty of his Cuban-trained GAP and a half-dozen Servicio officers to protect him in the La Moneda presidential offices. Once Allende realised he could not hold off the military, he decided not to even try to incite popular action against the putschists. This was likely in part because Allende understood after what happened in June that the population would not answer such a call, but there was a genuine desire to avoid needless bloodshed, too, and considerable bravery in Allende’s decision to die alone at his post rather than accept the offer of a way out.

“Surely this will be the last opportunity for me to address you”, Allende began his last speech on the radio. Blaming “foreign capital, imperialism, together with the [force of] reaction” for having “created the climate in which the Armed Forces broke their tradition”, Allende signed off: “Surely Radio Magallanes will be silenced, and the calm metal of my voice will no longer reach you. It does not matter. You will continue hearing it. I will always be next to you. At least my memory will be that of a man of dignity who was loyal to his country. … Long live Chile! Long live the people! Long live the workers! These are my last words, and I am certain that my sacrifice will not be in vain”.

Allende killed himself with an AK-47 presented to him by Castro, but Castro announced that Pinochet’s men had mown down Allende in cold blood and this was to become an article of faith in much of the world—still is in places. Combined with the bravery and drama of the last stand, the Allende cult was already beginning within days. For the global Left, there had been nothing like it since Ernesto “Che” Guevera, Castro’s murderous Argentine deputy, had been killed in Bolivia in 1967. The Soviets promoted the Allende sainthood cult, and managed to get a secondary cult going around Luis Corvalán, the Chilean Communist Party leader, who was imprisoned soon after the Pinochet takeover.

Pinochet’s regime killed or “disappeared” about 3,000 people and arbitrarily imprisoned 27,000, torturing many, during its seventeen years in power. Given Pinochet’s prior reputation as a colourless functionary and the Chilean military’s apolitical record, the ferocity with which the Communist movement, the broader Left, and ultimately all overt dissent was suppressed was shocking. This, the Allende cult, and anti-Americanism were among the factors that meant Soviet active measures—especially forged documents “showing” links between Pinochet’s secret police and the CIA—were pushing at an open door with much of the world’s press, including liberal outlets in the United States itself. In 1976, at the height of the Khmer Rouge’s “Killing Fields” that exterminated 1.5 million Cambodians out of a population of 7.5 million, The New York Times had four articles on the abuses of human rights in Cambodia and sixty-six on the same subject in Chile.

The unexpected savagery of Pinochet’s regime was a gift to the KGB in another way: it helped to erase from memory what Allende had actually done and why he had fallen. How far democracy had already been demolished, the misery in Chile on the eve of the coup, and the quiet yearning among much of the populace for an end to be made of the government was buried. By stepping in before Allende completed his Revolution—before the GULAGs, the mass-crimes, and potentially a civil war—Pinochet allowed Allende’s memory to feed on the afterglow of the Chilean constitutional order he had destroyed. The aura of constitutionality still clings to Allende, despite his regime trampling the constitution, because he came to power through elections. Pinochet’s blatant transgression of constitutionality denies him any claim to legitimacy.

Post has been updated with details about the Statute of Democratic Guarantees, Frei, and the 22 August 1973 Chamber of Deputies resolution.

Ah yes, the invariable game of generals on thrones that comes with supression of communists in the Cold War. Prior to the events of 1973 the words "Jakarta is coming" appeared as grafitti around Santiago. In fact the CIA had distributed what might be called a "playbook" of methods developed by Indonesians in their genocide (or politicide) of +500,000 communists in 1966-67. I studied the historiography of that episode and see many parallels with the Chilean example. No one knew which way Suharto would go; in fact, his communist friends in the general staff thought he was their pal right up to the end. He had attended the wedding of Colonel Untung, a former subordinate who started the botched 30 September coup. Both the UK and the CIA (with Australian help) "created the conditions" by creating a friendly media environment (radio, largely) for Suharto across the archipelago. Indeed, the UK may be held more responsible for creating those conditions through the defeat of Sukarno's forces in Malaysia. Both powers even facilitated events later by providing secure radio communications. However, neither the US nor the UK had foreknowledge of the events of 30 September. Benedict Anderson even suggests that the communist officers who launched the failed coup did so after staying up all night conducting divinatory mystic rituals. No intelligence agency could ever see such a chain of events coming. Rather, the art of covert operations in such situations is agile reaction to events. Suharto made a private agreement with the UK to withdraw troops from Kalimantan within 48 hours, but that still came after events that MI6 could neither foresee nor control. The CIA set out to learn from the Indonesians and pass on their lessons, they did not start the events or invent the methods.