Reduced, But Rebuilding: United Nations Reports on Islamic State and Al-Qaeda

The United Nations Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team released its latest report on the Islamic State (IS) and Al-Qaeda on 11 July. The Monitoring Team, which releases reports every six months, notes that the issues that have recently “preoccupied” it are “the spread of terrorism in Africa and the implications of the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan”, and these “remain unresolved and continue to represent major concerns”. But in first half of 2022, “the most dynamic developments” have taken place in IS’s “core area”, i.e. Iraq and Syria. The report says that the threat from IS and Al-Qaeda “remains relatively low in non-conflict zones”, such as Europe, but the “threat remains high” in “areas directly affected by conflict or neighbouring it”, specifically “Africa, Central and South Asia, and the Levant”. IS “poses the more immediate threat in this regard, although some regard Al-Qaeda as the more dangerous group in the longer term.” IS also has the legacy of the human networks that directed the foreign fighter flows to Iraq and Syria as a “major potential threat multiplier”.

AL-QAEDA

Unquestionably, the most important finding of the Monitoring Team is that Al-Qaeda’s emir, Ayman al-Zawahiri, is “confirmed to be alive and communicating freely”. There were reports in late 2020 that Al-Zawahiri had died. It is no surprise that “Al-Zawahiri’s apparent increased comfort and ability to communicate has coincided with the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan and the consolidation of power of key Al-Qaeda allies within their de facto administration.”

“Al-Qaeda is not viewed as posing an immediate international threat from its safe haven in Afghanistan”, says the Monitoring Team, since it “does not currently wish to cause the Taliban international difficulty or embarrassment” and “because it lacks an external operational capability”. This is interesting because, while Al-Qaeda has clearly reoriented over the last decade, strategically and ideologically, to a more localist focus in the Muslim world—and it is surely true that the devastating toll America’s retribution for 9/11 inflicted on the organisation has influenced this decision to avoid direct collisions with the U.S. where possible—questions have remained about whether Al-Qaeda could restart its war with the “far enemy” if it wanted to. The Monitoring Team suggests it could not.

That said, the report goes on to say that Al-Qaeda wants to recapture leadership of the jihadist movement from IS and Al-Qaeda’s “propaganda is now better developed” for this competition. The report is likely alluding to the ‘I Told You So’ narrative Al-Qaeda can use after the destruction of IS’s caliphate. Depending on events, Al-Qaeda “may ultimately become a greater source of directed threat”, the report notes.

Pressure on Al-Qaeda’s leadership has “eased”, according to the Monitoring Team, and the “international context is favourable to Al-Qaeda”. The report discusses the Hittin Committee, presumably named for the battle in 1187 where Muslim forces led by Saladin al-Ayyubi shattered the Latin States that had been formed after the First Crusade had recovered Jerusalem for Christendom a century earlier. The Hittin Committee is the body that coordinates Al-Qaeda’s global leadership. The report says that Africa has been prioritised over Yemen by the Committee, and names the Al-Qaeda officials next in line after Al-Zawahiri as:

Muhammad Saladin Zaydan (Sayf al-Adel): an Egyptian national, Al-Qaeda’s deputy based in Iran. Zaydan was the head of Al-Qaeda’s military council, but it is possible he has been replaced by Faysal al-Khalidi (Abu Hamza al-Khalidi), identified, when sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury in 2016, as Al-Qaeda’s “Military Commission Chief”, who inter alia acted as liaison between Al-Qaeda and the Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP) or “Pakistani Taliban”.

Muhammad Abbatay (Abd al-Rahman al-Maghrebi): a Moroccan national, the “general manager” of Al-Qaeda, a son-in-law of Al-Zawahiri’s, also based in Iran, though it seems semi-frequently travelling back and forth to Pakistan. Abbatay is simultaneously one of Al-Qaeda’s senior media officials.

Yazid Mebrak (Abu Ubayda Yusuf al-Anabi): an Algerian national in charge of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) since Abd al-Malek Drukdel (Abu Musab Abd al-Wadud) was killed in June 2020.

Ahmed Umar (Ahmed Diriye or Abu Ubayda): the leader of Al-Qaeda’s branch in Somalia, Al-Shabab, since 2014.

The report hardly needs to spell out that the needless catastrophe of permitting a Taliban victory in Afghanistan has been a “motivating factor” for jihadists. The Monitoring Team attempts to distinguish between the Taliban and Al-Qaeda, but even in their own description the distinction collapses in on itself. “Al-Qaeda leadership reportedly plays an advisory role with the Taliban, and the groups remain close”, says the report. Al-Qaeda’s presence in Afghanistan is apparently heaviest in the south and east, yet the report notes that its operatives have spread out west, as far as Farah and Herat, and there are at least intentions to “establish a position” in the north. The report says on the one hand that Al-Qaeda, while it obviously “enjoys greater freedom in Afghanistan under Taliban rule”, has “confine[d] itself to advising and supporting the de facto authorities”, but then notes that fighters from Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS)—the AQC presence in, and members from, Bangladesh, Burma, India, and Pakistan—“are represented at the individual level among Taliban combat units”. Forces that interwoven are not separate in any sense that matters. Another case is Jamaat Ansarullah, a unit “closely associated with Al-Qaeda”, which the Taliban was able to order deployed on the borders with Tajikistan in the autumn of 2021 after Dushanbe displeased them.

The report touches on Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP) or the “Pakistani” Taliban, noting that it “constitutes the largest component of foreign terrorist fighters in Afghanistan (between 3,000 and 4,000)” and had entered into a nominal ceasefire with the Pakistani state on 3 June that was “brokered” by the Taliban. The report does not get into it, but the TTP is intriguing mostly because of the disputation about what it actually is. There is no doubt TTP is entangled with Al-Qaeda and formally pledged to the “Afghan” Taliban leader; rather than a hostile element for the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), it looks like just one more of its instruments, though with the complication of IS infiltration in recent years.

AL-QAEDA IN YEMEN

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) “remains the most important Al-Qaeda affiliate for the dissemination of propaganda”, says the Monitoring Team, and “poses a persistent threat in Yemen, across the region and abroad, where the group aspires to revive an international operational capability”. Despite the loss of its overall military commander, Salih bin Salim bin Ubayd Abolan (Abu Umayr al-Hadhrami), in January 2022, AQAP “maintains strongholds” in Marib, Abyan, and Shabwa, “where most leaders and fighters are located”, with a smaller presence in Hadramawt, Mahra, and Jawf. Most AQAP members are Yemenis, according to the report, “supplemented by small numbers of foreign terrorist fighters”. AQAP also replenishes the ranks by freeing its operatives from prisons, the report notes, most recently in Hadramawt in April. Jihadist prison-breaks are a long-standing problem in Yemen.

One Member State says that AQAP runs itself through a series of committees, with Sa’ad bin Atef al-Awlaki overseeing the military committee and other leaders controlling the “security, legal, medical, and media committees”, though “[t]he finance committee has been disbanded owing to leadership losses”. AQAP makes its money from “kidnapping for ransom, looting and robbery, in addition to remittances from overseas relatives of AQAP members”, according to the report. In terms of its offensive capacity, as well as the Hadramawt jailbreak, AQAP is alleged to be working on “maritime operations” and has undertaken “small-scale operations” against Iran’s Ansarallah (Huthis), “primarily” in Bayda and Marib.

But here is where it gets very interesting: “one Member State reported collaboration between AQAP and Houthi forces, with the latter sheltering some AQAP members and releasing prisoners in return for AQAP undertaking proxy terrorist operations and providing operational training to certain Houthi fighters.”

It had been known for many years that AQAP had a problem with (particularly Saudi) spies, something AQAP openly admitted in late 2018. A year later, AQAP offered a public amnesty for spies who confessed and repented. Less well-known is that Al-Qaeda in Yemen has had a cooperative relationship with the Huthis back to the 1990s, when Al-Qaeda forged its relations more broadly with the Iranian theocracy; their mutual hatred of Saudi Arabia was and is a binding agent. Dr. Elisabeth Kendall pointed out two years ago that there is ample evidence—visible in outline if not in detail—of states, specifically Iran, manipulating and even fabricating jihadist operations under the AQAP label, which at this stage “has started to lose meaning”—complicating the Monitoring Team’s estimate that AQAP has “a few thousand fighters”. (It is a similar story with IS in Yemen: see below).

What is happening with AQAP is not an isolated phenomenon. Al-Qaeda’s designation as a “non-state” actor was always a bit blurry, given its role in Sudan up to 1996 and its attachment to Pakistan’s Taliban in Afghanistan after that. At the present time, states probably have more influence and even control over Al-Qaeda than ever before. This is particularly true of the affiliates, whether it is the ab initio questions about Algeria’s secret police in West Africa or the Iranian inroads in Somalia.

For all of AQAP’s problems—leadership decapitation, infiltration, fragmentation—the Monitoring Team reports that its strategy of exploiting the conflict to gain local acceptance is still working: it has been able to “embed with local tribes and thereby gain supporters”. And AQAP has been buoyed by the Taliban-Qaeda takeover in Afghanistan, which imparted to jihadists the lesson that setbacks can be overcome; all that is needed is patience.

AL-QAEDA IN WEST AFRICA

The main Al-Qaeda fighting force in West Africa is the conglomerate known as Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimeen (JNIM), led by Iyad ag Ghaly, which operates “a large-scale insurgency in parts of Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso”. JNIM was created to assist Al-Qaeda in navigating the ethnic and linguistic barriers as AQIM, a mostly Algerian organisation, pushed southwards into non-Arab areas. JNIM’s leader answers directly to AQIM leader Yazid Mebrak, who is, the Monitoring Team explains, the “strategic link” to Al-Qaeda Central (AQC) and “promotes JNIM strategy within the Hittin Committee”.

Ag Ghaly’s two primary deputies are Amadou Koufa, once the leader of the “Macina Liberation Front” and now a battalion commander within JNIM, helping the group spread out from Macina to the north, south, and east of Mali’s capital Bamako, and Sidan Ag Hitta (Asidan Ag Hitta or Abu Qarwani), who is based in the Kidal area and “plays a key logistical and operational role” in JNIM, says the report. Hitta is a relative of Drukdel’s and was “involved in the transfer of AQIM from Algeria to Mali”. The emir of Timbuktu, Talha Al-Libi, “supports JNIM logistically”, and the emir of Menaka, Faknane Ag Taki, is “more involved in the campaign against ISGS in the Ansongo-Menaka wildlife reserve”. ISGS is the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, which was rebranded as Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP) in March.

External networks feed into Mali’s troubles. Al-Qaeda’s presence in Libya, centred on the cities of Awbari and Sabha in the centre and south-west, are “home to the main terrorist structures” in the country, and from that base, “rely[ing] on its tribal platforms”, Al-Qaeda has been able to “send reinforcements to northern Mali”, the Monitoring Team documents. But the primary exacerbating factors are domestic. Mali has been racked with political instability: it was a military coup in March 2012 that allowed the north of the country to fall under AQIM control, an experiment in jihadist governance only rolled back by French intervention in January 2013, and further army takeovers in August 2020 and May 2021 have done nothing to help the situation.

AQIM has taken advantage of the January 2022 military coup in Burkina Faso, expanding into the country “along route nationale 18”, with “support” from Ansarul Islam (AUI), “most” of which has now joined JNIM, according to the Monitoring Team. AUI’s old emir, Jafar Dicko (Abdoul Salam Dicko or Amadou Boucary), remains as its unit leader, though he now operates, by the account of one Member State at least, “directly under the command of Mebrak”. Another piece of the connective tissue in Burkina Faso is senior JNIM operative Sekou Muslimu, who “ensures liaison” with AUI.

In addition, “JNIM recruits from Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, and Togo are trained in Burkina Faso prior to being redeployed to their countries of origin”, the report notes, meaning Al-Qaeda is, rather than drawing fighters into one theatre, spreading its tentacles through more states in West Africa.

The Monitoring Team makes claims for counter-terrorism successes in the French Operation BARKHANE, which works with the Sahelian governments to suppress jihadism. It points to the elimination of Yahia Djouadi (Abu Yahia al-Jazairi or Yahia Abu Amar), once the AQIM emir of post-Qaddafi Libya, north of Timbuktu in February 2022, and the killing of Samir al-Bourhan, a legacy jihadist from the Algerian war in the 1990s, in April. There have been scores of Al-Qaeda jihadists killed in Burkina Faso, some in Mali, and even groups in Benin. But the report points to concerns: France began its troop withdrawal in February, which is planned to be completed this year, and there are already signs this “may jeopardize past counterterrorism efforts”. JNIM and ISGS/ISSP “agreed to a joint ceasefire in the last week of May 2022 to focus their efforts against Malian forces” In the shadow of Afghanistan, this is alarming.

A curious omission from the report is the role of Russia in pushing the negative trends in West Africa, with its escalating deployment of troops—usually flagged as part of the “Wagner Group”, a nominal private military company that is a front for Russian military intelligence (GU, formerly GRU)—and deepening relationships with the region’s military and intelligence structures, whether they overtly control the governments or not.

Russia’s fingerprints were all over the 2021 Malian coup, and since then all subtlety has been set aside as the Russians take over French positions in the country and the junta tries to hurry along the French exit. There was every indication from the beginning that something similar happened in Burkina Faso earlier this year. This Russian template has been played out, or is underway, elsewhere in Africa: in Sudan, the Central African Republic, parts of Libya, Madagascar, and Mozambique. In all of these cases, Russia follows the old Soviet model of sending military and intelligence “advisers” and ever-increasing numbers of troops, removing figures who get in their way, and colonising African states from the inside-out.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February, France’s “independent” policy—one far more friendly to Moscow than the rest of NATO—has been on full display, and has been repaid by Russian ruler Vladimir Putin repeatedly humiliating French President Emmanuel Macron. This is a repeat of what happened in Africa over the last few years, where France tried to share security responsibilities in its Imperial sphere with Russia, and the Russians subverted the French at every turn. The result is not only humiliation for Paris, but disaster for West Africa: as has been demonstrated in Ukraine, the Russian military is a hollow structure, and cannot bear the weight of the tasks set for it.

A final note in the report about Al-Qaeda in West Africa is Ansaru—formally, Jama’atu Ansarul Muslimina fi Biladis Sudan (Vanguards for the Protection of Muslims in Black Africa)—which on 31 December 2021 pledged allegiance to JNIM, creating “significant concern” for Nigeria, “especially as its area of operations could blend with those of serious crime groups and some former Boko Haram operatives in the States of Kaduna, Katsina, Niger and Zamfara”. (The status of “Boko Haram” within the Islamic State is clarified below.)

AL-QAEDA IN SOMALIA

Al-Qaeda’s Somali branch, Harakat al-Shabab al-Mujahideen, carried out “some of largest attacks … in recent years … in early 2022”. Al-Shabab has between 7,000 and 12,000 fighters and “generates millions of dollars of revenue from its taxation of all aspects of the Somali economy”. Al-Shabab’s total annual revenue is between $50 million and $100 million, by the Monitoring Team’s estimate, with about one-quarter spent on weapons and explosives and some money channelled “directly” to AQC, according to “one Member State”.

AL-QAEDA IN SYRIA

Al-Qaeda’s presence in Syria is confined to the north of the country, concentrated in Idlib province, which is under “near total control by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)”, which was once the overt Al-Qaeda’s branch in the country known as Jabhat al-Nusra and has since 2016 claimed to disaffiliate from AQC. The Monitoring Team describes HTS, led by veteran jihadist Ahmad al-Shara (Abu Muhammad al-Jolani), as the “predominant terrorist group in Idlib with some 10,000 fighters”, including 300 Russian nationals.

Within Idlib, there is also Tandheem Hurras al-Deen, the declared Syrian Al-Qaeda branch since February 2018, which is led by Samir Hijazi (Faruq al-Suri or Abu Hammam al-Suri), who was part of the Al-Qaeda cell that included the founder of the Islamic State movement, Ahmad al-Khalayleh (Abu Musab al-Zarqawi), which moved to Saddam Husayn’s Baghdad in early 2002, a year before the invasion. After that, Hijazi was involved in jihadist activity in the Levant, sometimes being imprisoned but always seeming to be released quickly by Bashar al-Asad’s regime and its allies, until the rebellion erupted in Syria in 2011, when he was released for the final time. Hijazi is said by one Member State to have been appointed to the Hittin Committee in 2020 or 2021, and “some” Hurras “members were also reportedly instructed to travel to Afghanistan but were unable or unwilling to do so”. Hurras “is estimated to retain a few thousand fighters, some with aspirations to attack the West”.

In terms of the relationship between HTS and Hurras/Al-Qaeda, the U.N. report is rather vague. It cryptically refers to Hurras as “the other Al-Qaeda-affiliated group” in Idlib, strongly implying that the Member States believe HTS remains affiliated with Al-Qaeda, despite its claims to have broken away six years ago. The only additional information given is that “HTS continues to seek to portray itself as opposed to international terrorism”, and to that end “regularly conducts hostile operations” against Hurras, though even that is qualified since HTS has released “a few” Hurras prisoners it has taken, ostensibly “on condition that they not carry out [foreign terrorist] attacks”.

The relationship between HTS and Hurras/Al-Qaeda is, by its nature, covert and complex, and thus it is contested—by participants, as well as observers. The Monitoring Team explains that the Islamic State has reinfiltrated Idlib and now uses the area as a “strategic location”, something that had become apparent after the last two caliphs were killed there, in October 2019 and February 2022. A further part of the picture in Idlib—entirely unmentioned by the report—is HTS’s de facto alignment with Turkey, and the Turkish influence over Idlib through its military outposts and economic leverage, amongst other things. With so many actors packed in so close together and such potentially wide divergence between public and private intentions, Idlib is an unusually murky situation: I recently tried to, if not untangle this, then lay out the options for how this all fits together.

One indirect way the Monitoring Team comments on HTS’s relationship with Al-Qaeda is in its brief discussion of the Eastern Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM), also known as the Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP).

There is an immediate controversy here because some scholars, notably Sean R. Roberts, have argued that ETIM never really existed, that ETIM’s designation by the U.S. as a foreign terrorist organisation (FTO) in 2002 was a political move to gain China’s cooperation in the Global War on Terror and non-veto at the U.N. Security Council over the “second resolution” on Iraq, and that the TIP is a separate phenomenon entirely, its claims to be the inheritors of ETIM notwithstanding, originating in 2008 with a video threatening the Olympics in Peking. When the State Department de-listed ETIM as an FTO in 2020 it did so “because, for more than a decade, there has been no credible evidence that ETIM continues to exist”, appearing to support Roberts’ framing.

Roberts is obviously quite correct that nothing said by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) should be believed and it seems entirely possible that, pre-2001, there was no group that called itself ETIM and the CCP used “ETIM” as a catch-all term for Uyghur dissidents to delegitimise them as “terrorists” by associating them with a group of Uyghurs around Hasan Mahsum (Abu Muhammad al-Turkestani or Ashan Sumut) who had forged links with Al-Qaeda in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan in 1997. More contestable is Roberts’ argument that not only was Mahsum’s relationship with Usama bin Laden tactical, since Mahsum was “a religious nationalist” focused solely on Xinjiang who “was neither a Salafist nor a proponent of global jihadism”—similar arguments have been used to distance TIP in Syria from “proper” jihadists—but “[t]here is no evidence that [Mahsum’s] group ever instigated violence inside China or anywhere in the world.” By Roberts’ reckoning, whatever could be called ETIM died with Mahsum in Pakistan in 2003 and even the TIP after 2008—“prolific internet video makers”, as he derisively refers to them—have never “orchestrated violence inside China”. Where Roberts is incontestable is that CCP claims of international terrorists operating in Xinjiang have provided a pretext for genocidal repression against the Uyghurs.

ETIM’s existence before 2001, its relationship with Al-Qaeda, whether it (or TIP) was involved in violence in China, and the extent and causes of that violence—resulting from concerted terrorist activity or solely as a reaction to state repression of peaceful political activity as Uyghurs grew more assertive in the wake of the Soviet collapse—are issues where consensus is elusive, not least because the available data is so meagre and politicised. What is less controversial is that TIP does exist now and has a significant presence in Afghanistan, where the CCP has gone after it with help from its Pakistani dependency, and Syria. In both places, TIP is indistinguishable from Al-Qaeda.

In the Monitoring Team report of July 2020—which, incidentally, recorded that Hurras “coordinates military activity” with HTS—the TIP was noted to be one of the factions of foreigners from which HTS is “composed”. TIP was said to be attempting travel from Syria, via Iran, to Afghanistan where the TIP “collaborates … with the Islamic Jihad Group, Lashkar-e-Islam and TTP [the ‘Pakistani’ Taliban]”, meaning the TIP functioned as a component of the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) network led by the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. Other evidence indicates the same thing. The TIP’s emir after Mahsum, Abd al-Haq al-Turkestani (whose real name might be Memetiming Memeti), has been identified as a member of Al-Qaeda’s executive committee since 2005; has been deeply involved with the Haqqani Network, a key node in the ISI network; and, since Pakistan’s jihadists reconquered Afghanistan in August 2021, Abd al-Haq has publicly appeared alongside senior Taliban-Qaeda regime officials. And this month’s report makes the same point in a different way. The Monitoring Team documents the TIP’s presence in Baghlan province in the far northeast of Afghanistan, in the border zone with Tajikistan and China, at the Taliban’s behest, and its “continuing [efforts] to strengthen its relations with TTP and Jamaat Ansarullah”, including on military training, while “seeking to embed itself in Afghanistan through various means, including marriage”.

In terms of Syria, this month’s report estimates the TIP has “between 1,000 and 2,000 fighters” in Idlib and says “[t]he group is closely allied with HTS in carrying out terrorist operations”. This is slightly different to the wording of the 2020 report that had the TIP as a component of HTS; it is unclear if this is intended to signify an empirical change in the TIP’s status. In either event, the fact remains that HTS is to the present working tightly with an Al-Qaeda group. The TIP in Syria is said to be “commanded by Kaiwusair”, about whom nothing is known except that he uses the kunya Abu Umar and seems to have replaced Ibrahim Mansur after he defected and was arrested in Turkey in September 2021.

THE ISLAMIC STATE

The “most dynamic developments” among jihadists in January-June 2022 was with IS at the Centre, specifically Syria, the report says. The most significant action was the massive jailbreak at Al-Sinaa prison in the Ghwayran area of Hasaka city, a ten-day siege at the end of January 2022. The Monitoring Team argues that the Sinaa prison break was of “dubious operational benefit to [IS] but a great propaganda success”, reinforcing IS’s propaganda about its announced “Breaking the Walls” campaign. “[M]ore jailbreak attempts should be expected, particularly in the Syrian Arab Republic”, says the report.

IS initially claimed that it had freed 800 jihadists from Al-Sinaa, though it did not repeat this claim in the write-up in Al-Naba. The Monitoring Team writes:

Most Member States estimate that between 100 and 300 fighters fled to the Badiya desert or crossed the border to Iraq. The number of fugitives is offset by the number of casualties the group took in executing the attack, limiting the net impact of the operation. No senior [IS] leader reportedly managed to escape.

Some analysts, while agreeing that about 300 IS jihadists escaped, have disputed that no senior IS officials were freed from Al-Sinaa, reporting that four leadership figures got out, including Abu Dujana al-Iraqi (an Iraqi) and Abu Hamza Sharqiyah (a Syrian).

In Iraq, the Monitoring Team says that “counter-terrorism pressure has produced arrests and enhanced law and order” in places, and the capture of Sami Jassim al-Jaburi (Haji Hamid)—the IS “finance minister”, who “served simultaneously in two additional positions”, as the caliph’s overall deputy and as a member of IS’s executive body, the Delegated Committee—has “disrupted the group, especially its finances”, with his roles now divided up between several people. But “active [IS] cells remain in the desert and remote areas” and insurgent-terrorist attacks have been ongoing “with strategic intent, in particular targeting infrastructure and agriculture”, notably in Diyala, Salahuddin, and Kirkuk. There was a particular escalation after the IS spokesman announced during Ramadan (in April) a global revenge campaign for the caliph being killed in February. By the evidence from one Member State, “recent attacks in these areas may be [carried out by] escapees from detention facilities” in Syria.

IS’s activity at the Centre “continued to inspire attacks in the wider region”, the report says, notably the attack in Israel on 27 March, and IS is working on “reviving its external operational capability” around the world, that is to say its ability to conduct international terrorism, but for the moment “its reach … remains limited”.

IS’s caliph, Amir Muhammad al-Mawla (Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi al-Qurayshi), was killed in northern Syria on 3 February, and six weeks later his successor, Abu al-Hassan al-Hashemi al-Qurayshi, was announced. Though IS has “suffered a rapid succession of leadership losses since October 2019”, when the then-caliph Ibrahim al-Badri (Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi) was killed, these have had an “as yet unknown impact on its operational health”—and the rest of the report suggests that these leadership losses have not impacted IS’s rebuilding.

“Despite leadership attrition, Member States observed no significant change of direction for the group or its operations in the core conflict zone”, says the report, and IS “remains a resilient and persistent threat”. IS is estimated to retain between 6,000 and 10,000 fighters spread between Iraq and Syria, “concentrated mostly in rural areas”, the deserts where IS has always implemented its recovery. IS has “mounted other sporadic attacks” in northern and eastern Syria—in southern Hasaka, and in Deir Ezzor, southern Raqqa, and the adjacent deserts of eastern Homs—and in southern Syria, in the province of Suwayda and in southwestern Deraa. “Member States believe [IS] has resumed its training activities that had been previously curtailed, especially in the Badiya desert”, the Monitoring Team reports. There has been “infrequent activity in Damascus”.

In terms of who Abu al-Hassan is, back in March this newsletter noted that the names circulating as credible candidates included three Iraqi nationals: Bashar Khattab Ghazal al-Sumaidai (Haji Zayd); the brother of the caliph killed in 2019, Juma Awad al-Badri; and Ahmed Hamed Hussain al-Ithawi (or Abu Muslim al-Ithawi). The Monitoring Team says that Al-Sumaidai is “cited [by Member States] as the most likely candidate” and Juma al-Badri is noted as a candidate. While Al-Ithawi was not mentioned in the report, “Another Iraqi candidate cited by some Member States as a potential leader was the head of the [IS] general directorate of provinces, known as Abd al-Raouf al-Muhajir.” Still, the Monitoring Team says that Abu al-Hassan’s “identity is not yet established”, and there is no clarification available on the Turkish claim in May 2022 to have arrested Abu al-Hassan in Istanbul.

The Monitoring Team touches on the issue of Abu Hamza al-Qurayshi, the IS spokesman since October 2019, who was announced dead at the same time IS admitted Al-Mawla was deceased. IS was decidedly vague about how, when, and where Abu Hamza was killed. The report writes that Abu Hamza “was killed, according to one Member State, in November 2021 in an airstrike in Aleppo Governorate.” This is plausible on the basis of known facts: Abu Hamza’s last speech was in October 2020, and a number of very senior IS officials have been killed in the Turkish-dominated areas of northern Syria.

THE ISLAMIC STATE’S STRUCTURE

Though IS “maintains two distinct organizational structures” at the Centre, one for Iraq and one for Syria, according to the report, where the “office of the general directorate of provinces” that manages Syria is known as “Al-Sham office”, the Monitoring Team nonetheless makes clear—sometimes despite itself—that the Islamic State is a unitary organisation with a single ultimate command structure all across the world.

Somewhat underlining the point, “Al-Faruq office”, established in Turkey to manage the parts of the IS network in the Caucasus, Russian, and “parts of Eastern Europe”, was “effectively closed down” by the Turkish government arresting “key” officials within it, after which Al-Faruq office and the IS network on Turkish soil was taken over by Al-Sham office. This is the fluid structure of a single entity with delineated responsibilities for individuals and departments in different countries, not a collection of independent groups with hard borders between them.

In Syria, one “strategic location” for IS is Idlib province in the northwest, “despite its near total control by” Al-Qaeda-derived HTS, the presence of the overt Al-Qaeda branch Hurras al-Deen, and the significant Turkish influence. The report does not dwell on how and why IS has found haven in Idlib, but a detailed discussion of this matter can be found here.

IS has adapted to the loss of its territorial caliphate, putting in place “structures … to sustain the group’s global capability and reputation”. The report documents that the nine IS wilayats (provinces) outside Syraq continue to develop, albeit at “uneven speeds in different locations”, and all are connected firmly to the Centre. IS is “organizing and directing [the foreign branches’] human and other resources”. IS has about $25 million in reserves, some estimate double that, mostly stored in Iraq, according to the Monitoring Team, and the “funding flows to global affiliates remains resilient … All transactions involving affiliates are directed by [IS’s] leadership”. IS in Afghanistan continues to receive regular funds and the Karrar office that handles Africa (see below) is said to have found South Africa to be of “emerging importance” in facilitating transfers.

IS established its regional offices outside Syraq “during the period 2017-2019”, as the group officially initiated its transition from state back to insurgency (a process that had been openly signalled and put into practice before that), as part of the preparations “to maintain its global presence following the defeat of the territorial ‘caliphate’,” says the report. IS has had “varying degrees of success” in establishing these offices.

The “most vigorous and best-established” of IS’s structures set up at the Centre to oversee the wilayats are:

Al-Siddiq office in Afghanistan, which “covers South Asia and, according to some Member States, Central Asia”;

Al-Karrar office in Somalia, which also covers Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC); and

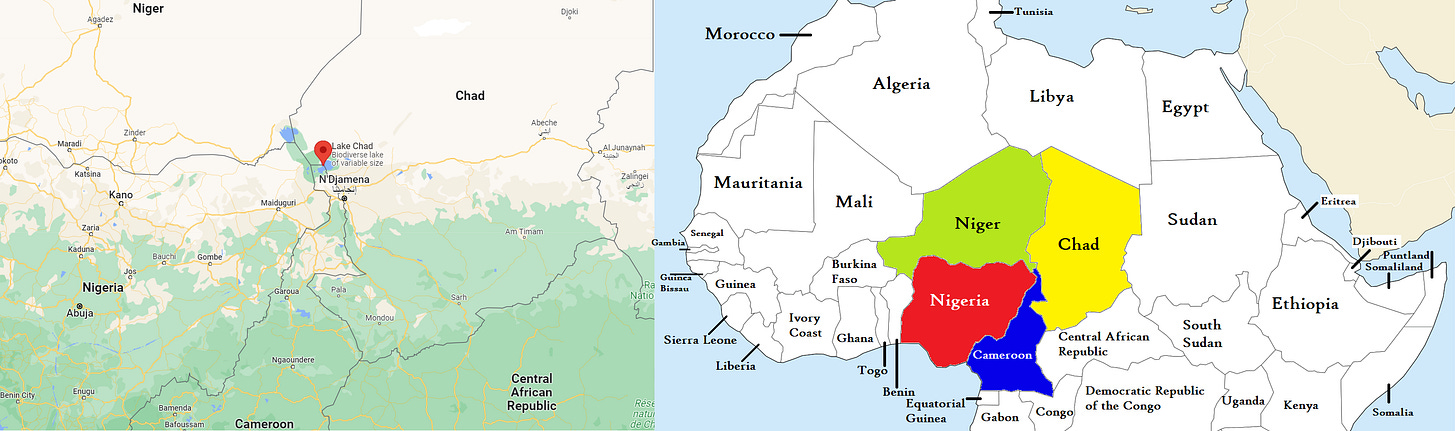

Al-Furqan office in the Lake Chad basin, where the borders of Niger, Chad, Cameroon, and Nigeria converge. The Furqan office covers these states in North Africa and the broader western Sahel, overseeing ISGS/ISSP.

IS’s other “three regional networks are low-functioning or moribund”, says the Monitoring Team, and these are:

Al-Anfal office in Libya, which covered “parts of northern Africa and the Sahel”;

The Umm al-Qura office “based in Yemen and … responsible for the Arabian Peninsula”; and

The Zu al-Nurayn office in the Sinai Peninsula “responsible for Egypt and the Sudan”.

As the Monitoring Team points out, “It is notable that two of the three most dynamic [IS] networks are in Africa, which is also the location of some of Al-Qaeda’s most dangerous affiliates.” IS has, in its weekly newsletter, Al-Naba, consistently highlighted its progress in Africa, particularly its war with Al-Qaeda and Christianity, for some time.

The same is true of the other most dynamic hub, Afghanistan, where IS had run a parallel state-to-insurgency transition as it lost leaders and its territorial holdings in the east of the country, and was spotlighting its “spectacular” terrorist atrocities and the growing capacity of its guerrilla operations—it was in Afghanistan that IS’s ongoing global “Breaking the Walls” campaign to free jihadist prisoners began in August 2020—long before the massacre at the Kabul airport during the NATO withdrawal and the escalation that has followed with Pakistan’s jihadists once again controlling the country.

ISLAMIC STATE IN MOZAMBIQUE

IS’s branch in Mozambique, previously known as Ahlu-Sunnah Wa-Jama (ASWJ) and called “Al-Shabab” by locals (not to be confused with Al-Qaeda’s Somali branch), has experienced “disruption in the leadership … following the deployment of regional forces”, the report says, and this has brought “a chaotic proliferation of smaller-scale violent attacks in remote villages throughout Cabo Delgado Province”. IS is “regrouping into smaller, more mobile groups”, and carrying out “[c]onstant attacks on villages, killings, beheadings, abductions, looting and the destruction of property [that] have caused a mass displacement” of about 80,000 people in the north of the country.

IS is led in Mozambique by Abu Yaseer Hassan (Abu Qasim), a Tanzanian national, and is estimated to have “between 200 and 400 active fighters”, after 100 jihadists were killed over the last six months by the “regional forces” deployed there—the unknown number of troops from the sixteen-state Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the 1,000 troops from Rwanda. It is not mentioned in the report that the deployment of these African troops came after Mozambique tried to rely on Russia for help against IS and the deployment of “Wagner” troops ended in a humiliating defeat. ISCAP’s operations in Mozambique are “led by Mozambicans who have extensive knowledge of the terrain” and the foreign fighters in the group are mostly from Kenya and Tanzania, with smaller numbers from the DRC, Somalia, and Uganda. IS-Mozambique uses Swahili as a common language, which “makes it easy for foreign terrorist fighters to communicate with one another and to assimilate”. The Tanzanians in the ranks have assisted IS’s escalation of cross-border attacks from Mozambique into Tanzania.

The Monitoring Team says IS-Mozambique “lost considerable momentum in April and May” 2022, partly because of “inclement weather” and partly in response to the Mozambican government’s offer of amnesty to those who laid down arms. Another signal of the adverse state of the group was IS-Mozambique releasing a number of hostages and the extreme state of malnourishment they were in—the group is struggling to feed its own members and could not afford to feed the hostages.

There is a very strange part to the Monitoring Team’s section on IS in Mozambique. The report mentions that IS has “recently referred to ASWJ as a separate affiliate”, referring without explaining to the restructure in May when IS-Mozambique was separated out from the Islamic State’s Central African Province (ISCAP), and then goes on to say that, despite IS-Mozambique issuing a bay’a (oath of allegiance) video to Abu al-Hassan on 1 April 2022, “regional Member States continue to be of the view that there is no clear evidence of ‘command and control orders’ from [IS] over ASWJ.” There is no context added—no mention of IS-Mozambique’s self-evident development, in media and battlefield tactics, along the well-established lines of an IS wilayat—which is either a gross oversight or means the report agrees with this view. Eight years after the creation of IS’s wilayat model, this is flabbergasting.

ISLAMIC STATE IN THE CONGO

What makes the Monitoring Team’s ambiguity over whether IS-Mozambique is “really” IS all the more baffling is that we have just been through this with the other component (now the sole component) of ISCAP, a Ugandan-origin group operating in the Congo that was once known as the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF). It took until late 2021 for it to be broadly admitted in the analytical community that ADF was in fact IS. ADF, which might well have gone over to IS as early as 2016 in secret and almost certainly had by April 2018, was publicly shown in a November 2018 U.S. sanctions notification to be receiving material support from IS Centre, and this was expanded in greater detail in March 2021 to identify IS’s presence in central and southern Africa. In between, in 2019, ADF publicly declared its bay’a to IS. Yet, well into 2021, detailed articles on the flow of IS personnel and money from the Centre to ADF, and the effect this had had in “dramatically improving training, tactics, and propaganda”, would insist on ignoring their own evidence to frame the issue ambiguously, saying IS was “giving the impression” it controlled ADF and “us[ing] them for propaganda purposes”.

The report at least avoids any misinformation about the former ADF branch led by Seka Musa Baluku being a part of IS since this was announced in July 2019. It was at this point that some ADF members split off, rejecting Baluku’s authority, and formed a unit loyal to Jamil Mukulu that was led by Benjamin Kisokeranio until his arrest in January 2022. Baluku released a video in April 2022 as part of the bay’at campaign for Abu al-Hassan and his ISCAP has seen a “significant uptick” in foreign fighter recruits from Kenya, Tanzania, and Somalia. The other major foreign contingents in ISCAP are from Rwanda and Burundi. ISCAP carried out four bombings in Uganda in October and November 2021, showing its capacity in that country, where “business owners” are among its “key sources” of finance. “Ugandan and Kenyan expatriates also generate wealth in countries such as South Africa, and launder proceeds” to ISCAP, the report notes. Alongside these local sources of funding, multiple ISCAP operatives have been arrested over the last six months while trying to travel to Syria, suggesting the group remains firmly entrenched in the Islamic State’s global network that provides training and resources to its various fronts as required.

ISLAMIC STATE IN WEST AFRICA

The Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP) was formed out of Jama’atu Ahlis-Sunna Lidda’Awati Wal-Jihad (JASDJ), better known as “Boko Haram”, in March 2015, but in August 2016 IS tried to remove the ISWAP leader, Abubakar Shekau, and appoint Habib Yusuf (Abu Musab al-Barnawi) in his place, leading to a schism. The larger ISWAP would be based around Lake Chad basin in north-east Nigeria and Shekau’s rump Boko Haram was based to the south in the Sambisa Forest, which is where the contest between the two was finally settled in May 2021 with Shekau’s death. The Monitoring Team says that Shekau’s faction has been “weakened by the transfer to ISWAP or surrender to the Nigerian Government of most of its fighters”. There report has no clarity on what has happened to Yusuf, who was himself removed as ISWAP emir in March 2019, and replaced by Ba Idrisa (Abu Abdullah ibn Umar al-Barnawi): “While some Member States reported [Yusuf] dead, others declared him active as the head of the Al-Furqan office.” There is good reason to think Yusuf is dead. The Nigerian army claimed in October 2021 to have killed the then-current ISWAP leader, Malam Bako; the report is silent on this. The intra-jihadist fighting and ISWAP’s leadership turnover has not brought much respite to Nigeria or Niger, however: “Violence remains endemic” with persistent “kidnappings for ransom and attacks on civilian and military targets”.

The Monitoring Team mentions that the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), which was announced in May 2015 and subsumed under ISWAP in March 2019, was once again made into an “autonomous [IS] province” in March 2022, but does not mention the new name: the Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP). The report is also silent on the leadership situation in ISSP/ISGS: the last emir, Lehbib Yumani (Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi), was killed by the French on or around 17 August 2021, which was announced by Paris a month later and confirmed by IS (albeit in passing) in October 2021. Mostly based in Mali and Niger, ISSP/ISGS has been pushed into the border area between the two states under pressure for JNIM, according to the report, and after fighting with “Dawsahak Tuaregs and local armed groups in Mali who rejected [IS’s] atrocities and extortion”, ISSP has “struggled” to maintain its foothold in the tri-border area further west in Mali, where the frontiers of Mali and Niger meet with Burkina Faso. Still, ISSP did launch a “campaign to create a second safe haven east of Menaka” in “late May” 2022.

ISLAMIC STATE IN AFGHANISTAN

The Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) has been led since May 2020 by Sanaullah Ghafari (Shahab al-Muhajir): the report does not add any clarity on whether Ghafari is an Iraqi, as some speculated. The report continues: “Other leadership figures are reported by one Member State to include Mawlawi Rajab Salahuddin (alias Mawlawi Hanas) as deputy, Sultan Aziz Azzam (spokesperson), Abu Mohsin (head of finance), Qari Shahadat (head of training), Qari Saleh (head of intelligence) and Qari Fateh (head of military operations).” The leader of Al-Siddiq office is Tamim al-Kurdi (Abu Ahmed al-Madani), unsurprisingly an operative IS sent from the Centre: “He was appointed by the [IS] general directorate of provinces and arrived in Afghanistan in 2020”. Along with the money IS sends from the Centre, there are efforts to send soldiers to ISKP: so far, Member States have “not yet observed significant flows of fighters from the [IS] core conflict zone to Afghanistan”, but that has more to do with logistical challenges and in time they will likely be overcome.

The Monitoring Team notes that ISKP has been at work—following the model of Libya and elsewhere—in trying to peel away jihadists from other groups, notably “attracting disaffected Taliban fighters”, and, by the evidence from one state, Uyghur militants from the TIP. ISKP has clearly escalated its activity since the fall of Kabul and the report says its “aims” have been to “undermine the credibility of Taliban security forces by demonstrating their inability to control the borders, and to attract new recruits from the region”. At this, ISKP appears to be succeeding: ISKP has spread into northern and eastern Afghanistan, has fired rockets into Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, and by all accounts has more Central Asian recruits now than it did a year ago.

Most importantly, the Monitoring Team writes: “It is unclear whether [ISKP] can regain lost territory in eastern Afghanistan”, but if they do “it may prove difficult for the Taliban to reverse such gains. According to one Member State, [ISKP] would then be positioned to develop a global threat capability from Afghanistan.” The Taliban, even when supported directly by the U.S., struggled appallingly against ISKP’s statelet in Afghanistan. The unravelling of ISKP’s territorial holdings had more to do with an internal strategic decision—not dissimilar to, and indeed roughly concurrent with, a decision made at the Centre to transition back to insurgency. There was never any reason to think the Taliban could contain ISKP, no matter how much support Pakistan, Iran, Russia, and China give them.

One of the most interesting parts of the report is evidence of ISKP funding coming from the Islamic State in Somalia (ISS). ISS, based in Puntland, has been “depleted” by Al-Qaeda’s Al-Shabab and now has no more than 280 members, but its leader, Abdul Qadir Mumin, a dual Somali-British citizen, oversees Al-Karrar office, which “one Member State” says has responsibility for Somalia, Mozambique, and DRC, and “acts as a financial hub”, distributing IS funds to its provinces. ISS collects money by extorting the shipping industry and populations (what it calls “taxes”), then sends some of this cash to ISKP: “One Member State reports that the Al-Karrar office facilitates the flow of funds to Afghanistan by way of Yemen, with a potential link to Kenya; while another asserts that the money is transferred using a cell in the United Kingdom.”

ISLAMIC STATE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

The consensus of Member States is that the IS threat in Southeast Asia has “largely receded”, with the notable exception of the southern Philippines where the former Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG), now the Islamic State East Asia Province (ISEAP), has about 200 fighters, led by Abu Zacharia (Jer Mimbantas or Faharudin Hadji Satar), who still mount “small-scale attacks”. The Philippine government’s very success, however, may be creating a new problem as ISEAP is pushed over the border into “parts of Malaysia”.

ISLAMIC STATE IN NORTH AFRICA

Islamic State Sinai Province, the former Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis (ABM) in Egypt, has concentrated around Rafah city and continued carrying out terrorist attacks. Overall, though, “the assessment of Member States is that the group is declining in strength. This is attributed to successful counter-terrorism operations by Egyptian forces as well as a concerted effort by the Egyptian Government in the Sinai area to address underlying grievances among local communities, including among Bedouin tribes”. The report says that “one Member State” (presumably Egypt) said IS-Sinai has “approximately 500 fighters”, based mostly in northern Sinai.

The Islamic State in Libya (ISL) “retains fewer than 100 fighters”, according to “one Member State”, and the Monitoring Team says ISL has been “weakened by leadership losses” and the U.S. raids in Sabha and Bani. While “some Member States have concluded … [ISL] is confined to southern Libya”, the group has sought to “reactivate its logistical nodes in the northern part of the country, in particular in Bani Walid and near the Tunisian border in Sabratah”, inter alia to allow it to replenish the ranks by bringing in foreign fighters, and, even in the south, ISL has continued to be able to carry out attacks in the examined period and has “established a new approach … to disperse and move in small groups to evade detection”. This reconstitution in the southern deserts was predictable after ISL lost its territorial holdings. ISL also does not seem to be completely isolated in southern Libya: it “may have established a link” with operatives in “the Sahel, Somalia, and the Sudan”; multiple IS operatives from Libya have been arrested in Morocco, some of them seeking to get to Afghanistan; one state reports that ISL has created a pipeline running in both directions with ISWAP in the Lake Chad basin; and another state reports that ISL “seeks to recruit migrants from neighbouring countries”.

ISLAMIC STATE IN YEMEN

The Islamic State in Yemen (ISY) has “battlefield experience [which] suggests that they remain a potential threat, but a lack of resources and leadership would inhibit any resurgence in the near term”, says the Monitoring Team. “The value of Yemen to [IS] may reside in the presence of the Umm al-Qura office of the general directorate of provinces and facilitation and financial links across the Red Sea to the Al-Karrar office in Somalia.” There are indications from one Member State that ISY has found some purchase in the local population, having “assimilated into various tribal forces in the country and been reintegrated into the overall Yemeni conflict.” Nonetheless, ISY “is considered to be overshadowed in Yemen by AQAP”: ISY has “not conducted any recent attacks” and “is on a downward trajectory”. This is to say the least of it.

As outlined above in the AQAP section, discerning who is doing what, why, and for whom is extremely difficult in the Yemeni context where allegiances are fluid and even the firmly committed actors cannot always be sure whose “grand design” they are involved in. Where the report at least inclines at the evidence that AQAP is being manipulated by states, there is no mention of this factor when it comes to ISY, where the evidence is probably stronger. The re-emergence of ISY in mid-2018, after it had been severely degraded by U.S. airstrikes, was a strange piece of business, as Dr. Kendall documented in great detail. During the 2018-20 period, ISY ceased attacks on the Huthis, the local manifestation of the Iranian Revolution, and instead “maniacally focused on provoking AQAP into open conflict”, writes Kendall, which succeeded: “both ISY and AQAP focused almost exclusively on killing each other.” There were some strong indicators that ISY was collaborating with the Huthis/Iran, and circumstantial evidence that “parts of both ISY and AQAP have been instrumentalized by regional rivals”, concluded Kendall.

JIHADIST TERRORISM IN EUROPE

The Monitoring Team has the threat level from IS and Al-Qaeda “remaining moderate” in Europe, which seems reasonable, but the rest of what it has to say in the section is questionable. IS and Al-Qaeda have “limited resources”, the report says, and since the elimination of the caliphate have been “reduced primarily to issuing appeals to sympathizers to resume attacks in Europe”. The report says “aspiring attackers are mainly autonomous, with operational and ideological independence from global terrorist organizations” and says recent IS attacks in Europe were “inspired” by the group “without material logistical or economic support”, chalking them up “primarily [to] individuals with mental health problems”. The Monitoring Team adds that “lone actor” (or “lone wolf”) attacks have “declined”, something that is not that surprising since the entire category is highly dubious in conception. There is something quite absurd in the contention that the recent prosecutions of “The Beatles” and the Bataclan killers have “deterred potential recruits” to organisations that have suicide built into their primary modes of attack.

The premises on which the Monitoring Team’s analysis proceeds are at variance with what is known about how IS and Al-Qaeda conduct external operations. The system of terrorism guides IS put in place has weathered the destruction of its lead operatives and had become untethered from the caliphate project long before the end: that infrastructure remains; whether it expands, time will tell. As mentioned, “lone wolf” terrorism is essentially a myth in general and demonstrably so with IS. Even on the Qaeda side of things, where foreign attacks have been de-emphasised for some time, the shooting at the Naval Air Station in Pensacola in December 2019 was directed by Al-Qaeda, not “inspired” by them.

The report is on firmer ground about the abysmally run prison systems for jihadists in Britain and Europe, specifically France, Belgium, and Spain—the most affected states on the Continent—where “radicalisation” in prisons in rampant and short sentences mean these people get out quickly, increasingly frequently after they have displayed false compliance with “deradicalization” programs. Likewise, the risk that “the flow of refugees arriving in Europe could mask travel by terrorists” is well-attested by available evidence, and the “database interoperability among European Union member States” is less a “critical gap” than a perpetual fantasy. The report sees “little evidence of systematic cooperation between transnational criminal networks in Europe and terrorist groups”, but the creation of sleeper cells, particularly by IS, is visible in the arrests—especially in Kosovo and involving Kosovar Albanians, interestingly.

IS in Libya has been able to move funds to networks in Spain and Italy, the Monitoring Team documents, and money has been moved by Al-Qaeda operatives between Idlib and Spain. The hawala system has, of course, been useful for these financial transfers, and according to the report Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies can finally claim a real-world use in moving and laundering funds for IS and Al-Qaeda. IS is even reported to be “providing tutorials on how to open digital asset wallets and make transactions using cryptocurrencies.”

The final point the Monitoring Team makes is about the highly dangerous situation in the Syrian camps, where the situation “grew more precarious and challenging during the reporting period”. One state estimated that there are 120,000 individuals in eleven camps and twenty prison facilities in Syria, one-quarter of them under-12. IS continues its “cubs of the caliphate” program to recruit children. 10,000 foreign fighters, many of them European, are held by the SDF/PKK. Al-Hawl is the most notorious camp: “some women” there are “considered among the most extreme [IS] members”. There have been assassinations in the camp and money flows freely from and to IS operatives outside the wire. $1,500 is enough to secure false documents and assistance in being smuggled out. With IS once again focused on “Breaking the Walls”, the jihadi proselytism within the camps, and the extreme reluctance on the part of states whose nationals are in the camps to take them back, there is not only no solution in sight; there is no sign of measures to prevent a bad situation getting worse.

Post has been updated.