Can We Ever Know How Many People Were Killed in Rwanda?

In 2020, David A. Armstrong II, Christian Davenport, and Allan Stam published an article in the academic Journal of Genocide Research, “Casualty Estimates in the Rwandan Genocide”. Though the paper did attempt to come up with an estimate, the number was not the point. The purpose of the article was to show how these estimates have been generated since 1994—and why none of them should be trusted.

The authors begin by noting that “state-of-the-art statistical tools require named, overlapping lists of victims, location, time and information about event type”. There is nothing of that kind for Rwanda. What we have, instead, are “incomplete surveys of (often) unidentified victims which have different spatio-temporal scopes and behavioural focus”. Put more simply, the sources for counting the death toll in Rwanda are demographic comparisons and interviews with witnesses, survivors and perpetrators.

Interviews can potentially be useful for piecing together what happened at an individual site on one day, but even a large survey of a Rwandan prefecture (province or state) asking people about lost family and neighbours introduces an incredible amount of noise into the statistics.

While the incentives for perpetrators to be deceptive in interviews are obvious, the incentives for survivors are no less apparent, especially in the years after 1994 when such stories are being told in the context of Paul Kagame’s stiflingly despotic Rwandan government having made speech that deviates in any way from the official narrative a crime under the laws against “genocide ideology” that can carry a life sentence. People making, or wishing to keep open the possibility of, asylum claims to try to escape the Kagame regime likewise have incentives to shade their stories.

But make the heroic assumption that data gathered from survivors is not polluted by wilful deception: the frailty of human memory and finding a representative sample—even for a prefecture, let alone if results from one area are going to be generalised to a national estimate—mean the confidence in any resultant estimate should be low.

The authors highlight six sources of data:

African Rights, an NGO founded in 1993, produced a report in September 1994, Rwanda: Death, Despair and Defiance, compiling “all available eyewitness accounts” and in its 1995 second edition reached previously inaccessible prefectures. Purporting to cover the whole country, it documented about 130,000 fatalities.

Human Rights Watch released, Leave None to Tell the Story, in 1999, again mostly from oral accounts: of Rwandans on all sides, diplomats, and United Nations officials. HRW’s intention was overtly activist—to “educate” and “bolster public support” for the trials of the accused genocidaires—but it ostensibly also gathered data from the whole of Rwanda. It documented about 40,500 fatalities.

IBUKA (“REMEMBER”), a Tutsi advocacy group formed in late 1995, undertook the “Kibuye Dictionary Project” from 1996 to 1999 that tried to identify all the victims in that prefecture and the circumstances of their deaths. Over 25,500 fatalities were listed.

The Ministry of Higher Education, Scientific Research, and Culture—a Cabinet Ministry of the Rwandan government—gathered data, in collaboration with other ministries, from November 1995 to January 1996 in a project called, “The Commission for the Memorial of the Genocide and Massacre in Rwanda”. The nationwide survey recorded approximately 755,500 fatalities.

The Ministry of Youth, Culture, and Sport was deputised—for reasons best-known to the Rwandan government—to identify and excavate mass-graves. Other ministries helped, including Defence. Forensic evidence was gathered and the country-wide project was completed the same year it was initiated: 1995. Nearly 823,500 fatalities were reported.

The Ministry of Local Administration and Department of Information and Social Affairs began, in 2000, an effort to count and name the victims of the 1994 killings, with the goal of discovering the most impacted zones for the purposes of deciding on aid allocations. Survivors and neighbours of the dead—or, in practice, missing—were interviewed and the 2002 report, “The Counting of Genocide Victims”, estimated nearly 940,000 fatalities.

The authors explain their methodology in using these sources thusly:

We approached this topic as a measurement problem. In this paradigm, a latent construct (i.e. the actual casualty figure) produces observed, error-laden indicators (our data sources). We then use the similarities in the relationships among the indicators to derive estimates … We use Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulation with essentially uninformative priors (i.e. where no source is privileged relative to others) to estimate the model. … We exclude the IBUKA data from the model because the patterns at the commune aggregate level are negatively related to those produced by other indicators.

The technical maths involved in developing the model is explained in the paper for those interested. For our purposes, it is enough to know the results:

Each of the accepted five sources can be used to generate a total death toll on their own. The lower confidence interval on the smallest tally is 42,000 and the higher confidence interval on the largest tally is about 1.5 million. These are surely, respectively, an underestimate and an overestimate.

Averaging the five sources gives an estimate of estimate “of just over 580,000 with an 80 per cent credible interval ranging from just over 500,000 to roughly 687,000”.

If the average is weighted “by the amount of available information in each source”, the figure becomes “730,000 (650,000, 845,000; 80 per cent credible interval).”

These figures are below the “over one million” figure that is often given for Rwanda’s nightmare in 1994, though the weighted average approaches the 800,000 that is another frequently cited figure. The authors make clear, however, that this is rather beside the point: “the exercise … highlights some fundamental truths about trying to derive casualty estimates from secondary sources—the most common way that this is done”.

First, “there are many arbitrary decisions required to generate casualty estimates”. Death tolls arrived at via some form of statistical process—or better yet, modelling—have the aura of Science about them; many interpret these outcomes as a just-the-facts enterprise. But it is interpretation all the way down. The authors are happy that their exclusion of the IBUKA data is defensible, but as they note their view is hardly unchallengeable, and if the IBUKA data is included it increases the averages by about 100,000 and also increases the uncertainty intervals.

Further, it is not included in this section of the paper, but alluded to earlier: the choice to focus on the actions of the Interahamwe and other government-aligned forces in the period April-July 1994 is not a neutral one.

One can set aside the terrible violence against Tutsis during the Hutu Revolution (1959-61) and the Tutsi reprisals in the first years of independence after 1962. By all means exclude, too, the massacres over the next decade, mostly against Tutsis but not exclusively. Including this history risks stretching the definition of “context” past breaking point. The extensive persecution of Tutsis under Juvenal Habyarimana (r. 1973-94), whose assassination was the trigger for the descent into darkness in 1994, is important to keep in mind if history is the matter at hand, but not especially relevant to the maths problem before us.

What is not so easily severed from the death toll calculation for 1994 is the ethnic civil war that began in 1990. The civil war is not just the context in which the wave of atrocities in April-July 1994 occurred; those atrocities are an inseparable part of the war. The Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) invaded Rwanda from Uganda in October 1990. Kagame took over the RPF after some early setbacks, waged an insurgency through 1991 and 1992, then managed to occupy the north of the country in early 1993. The Arusha Accords in August 1993 paused the fighting and were supposed to lead to a power-sharing government. The peace process stalled, came under tremendous pressure after Tutsi officers assassinated the Hutu president of neighbouring Burundi in October 1993 and launched pogroms that sent waves of Hutu refugees with horror stories into Rwanda, and then dissolved with Habyarimana’s murder. Whether the RPF or the “Hutu Power” faction were responsible for killing Habyarimana remains uncertain, but both went back to war. Over the next three months, the Hutu Power forces warred against the “enemy within” and the RPF undertook its methodical conquest of the Rwandan State, committing terrible crimes against Hutu civilians and anybody else in its way.

Nor is it so easy to ignore the aftermath. The Rwandan government forces and about two million Hutus fled before the RPF advance and gathered in refugee camps in the border zone in eastern Congo. The war continued. Cities like Goma became nerve-centres of a brutal cross-border insurgency bent on a Hutu restoration and Kagame repaid the area in kind with indiscriminate punitive raids. In late 1996, Kagame outright invaded the Congo, his troops slaughtering tens and maybe hundreds of thousands of Hutus of all nationalities as they moved towards Kinshasa. By May 1997, General Mobutu had been deposed and a Kagame-aligned ruler installed in the Congo—only for him to try to break free of Kagame’s tutelage a year later. The Congo collapsed into the “African World War”, faintly structured around pro- and anti-Rwanda allegiances, but in the event it was a war of all against all within the Congo that lasted five years and drew in nearly every State in southern Africa and some from beyond. Millions perished, including virtually whole peoples like the Bambuti pygmies, who were enslaved, raped, murdered, and cannibalised—usually in that order because of a belief consuming their flesh conferred magical powers.

Now, looking at this sequence of events: Where do you draw the line?

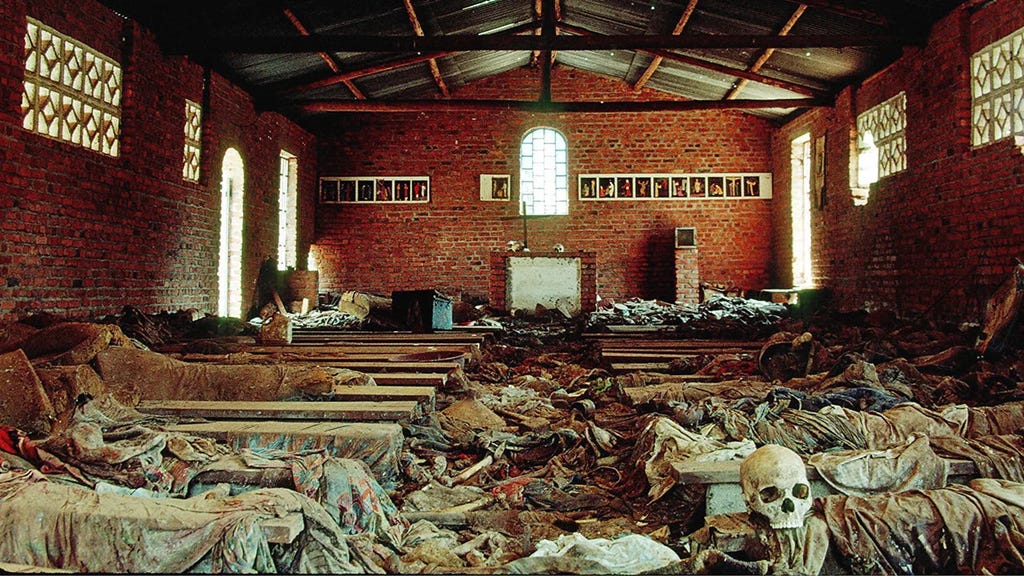

Restricting things to April-July 1994 in Rwanda invites the question: Why count Rwandans killed by the Interahamwe and not by the RPF? As one of the authors has explained elsewhere, the view many have of Rwanda’s carnage—just in those hundred days—as being almost solely a story of Tutsi suffering, with maybe ten percent of the victims being Hutus, is simply wrong. The scale of the RPF’s crimes were much greater than that. Even the Interahamwe’s victims were significantly Hutus, whether it was Hutus mown down and burned alive when the death squads indiscriminately attacked terrified civilians of all ethnicities gathered in municipal buildings and churches, or the death lists for Hutu oppositionists sent out by the military caste that took over after Habyarimana was dead.

As it happens, the death tolls for the April-July 1994 period, especially those arrived at using demographic surveys, usually in fact include Rwandans killed by all perpetrators, even if the results are presented otherwise by the Kagame government and its sympathisers. That goes for the ministry surveys and, therefore, the averages in the Armstrong et al. paper. Trying to isolate the Rwandan genocide figure from this top-line fatality total—even if it was accurate—is a separate and daunting task, the utility of which comes into question.

An alternative is to stick to Rwandan territory, but tally from 1990 to 1994. Or maybe count from 1990 through the border skirmishes of 1994-96 and the First Congo War (1996-97) with its Rwandan-centric nature, but exclude the mess of the Second Congo War. The option of including the whole lot in Rwanda and the Congo up to 2003 might make the most historic sense, treating the sequential events as the integrated crisis they were, but dealing with all that as “the Rwandan genocide” is a strain on lexicography apart from anything else.

People will differ and that is fine. The point is just to recognise that the choice of time and space is interpretive, and the utility of any quantitative conclusions limited to that extent.

The second element the authors highlight is that any calculation “require[s] the researcher to either imply or express belief about the veracity of different sources”:

By either choosing to use a single source or aggregate multiple sources, researchers are making a statement about their belief in the utility of each measure. Not making an explicit choice (i.e. just using a single source or averaging across all sources with equal weight) is itself a statement of faith—specifically, that all sources are equally reliable. In any event, this exercise has failed to remove us from the situation where our conclusions about what happened are based on our prior beliefs about the reliability of the data.

The third element is Rwanda-specific—about the communes and the data needed to calculate daily and weekly death tolls, which does not exist—and the fourth, related to the second, is another general factor: transparency about the data underlying these estimates.

The authors have been criticised—they do not put it this bluntly, but mostly because of their findings, which complicate the Kagame government’s public messaging and the foundations of its legitimacy, inside Rwanda and in the West. This criticism, however, has presented itself as being about their methods. The authors thus raise this fourth point as something of a rebuttal, but it is of much wider import. “Our approach is consistent with a growing body of social science research … that seeks to disaggregate conflict processes within largescale territorial units”, the authors note, adding:

[W]ithin our research we have consistently strived to be transparent—a practice not often followed and/or respected by others in the field. At any point in time within our project, researchers could access the raw material that we collected, the code used to generate estimates and make decisions about what they wanted to trust or not trust.

Catty, yes. But fair.

As the paper documents, “no one has said that the various Ministry reports issued by the Rwandan government were flawed”. Indeed, they all “received a significant amount of praise”, and the authors made use of them on the basis of this consensus—even translating them into English so that a wider pool of scholars could access them and use them to check the authors’ work if they wished. Some said Human Rights Watch “might not have uniformly well-covered the entire country” and the Kibuye data from IBUKA was acknowledged as suffering “from a few limitations but nothing at all that impugned the whole effort”. The outstanding exception is African Rights, one of whose founders revealed comparatively recently “issues” with the NGO that do cast doubt on its entire output.

Similarly, the authors have always “provided estimates of the error”, which they correctly point out “deviat[es] from the majority of practices within all of the media and most of the scholarship reported over time.” So attacking the authors for their sourcing is disingenuous—if it is confined to them alone. “What would have been a reasonable critique to make of our project was that the underlying source material was fundamentally flawed”, the authors write. Which gets to the nub of things.

The conclusion one takes away from the paper is:

Given all of the caveats and choices that are required (some of which cannot be justified statistically), we have always felt that the most defensible position is that no clear casualty figure emerges.

More than thirty years after the meltdown in Rwanda—which took place in the full glare of the 24/7 media cycle and has been a topic of relentless fascination for the reading public, generating ongoing coverage over the decades and an exhaustive body of academic literature—we simply do not know how many people were killed that year. And if that raw total remains out of reach, the chances of ever disaggregating the numbers for who killed who are remoter still.

For regular readers, this will not be a surprise. A few months ago, I explained in some depth the processes that produce most wartime casualty figures: they almost always come from one of the combatants, are generated with political intent, and are frequently just made up, but they are “sticky”, in part because lots of people in influential positions gain an interest—often for the best of motives, though not always—in perpetuating them. That article was framed around the claim that twenty-seven million Soviet citizens were killed in the Anti-Nazi War. We can be sure that number is false, and not sure of much else. We can have reasonable confidence that the number is too high, but even there one falls into the trap of the propagandists who authored the number by “anchoring” estimates to a figure that should never have existed.

Rwanda’s great counterpart as a media war in the 1990s was Bosnia, where we did eventually get a decent ballpark casualty estimate, one significantly lower than the figure conjured up by the Muslim government, and including many more of that government’s victims than anybody in real-time admitted existed. That said, knowledge of the lower casualty finding has been somewhat suppressed by a ferocious information campaign from the Muslim government and its supporters, and the exact ethno-religious breakdown of the Bosnia fatalities remains genuinely contested. More to the point, even if the lower estimate had cut-through broadly, by the time it was discovered in the 2000s it was too late to offset Sarajevo’s use of the higher number for political warfare.

An obvious implication of the inability of scholars to uncover credible fatality totals for historic wars as extensively studied as the Second World War, Rwanda, and Bosnia is that honest people should have as their operating assumption that death tolls given for ongoing wars are fabricated, all the more so when the undisguised source is one of the combatants.

There is another conclusion Armstrong et al. come to, which is not without contemporary relevance: “From the beginning, we have maintained that the type of information necessary to make the determination of genocide [in Rwanda] was near impossible to acquire (i.e. the intent of all perpetrators and the actual or perceived identification of all of those who died).” This is a subject of its own that will be taken up at some point in the future.