The Lost World of the Titanic

Book Review of ‘A Night to Remember’, the Classic Story of the Disaster

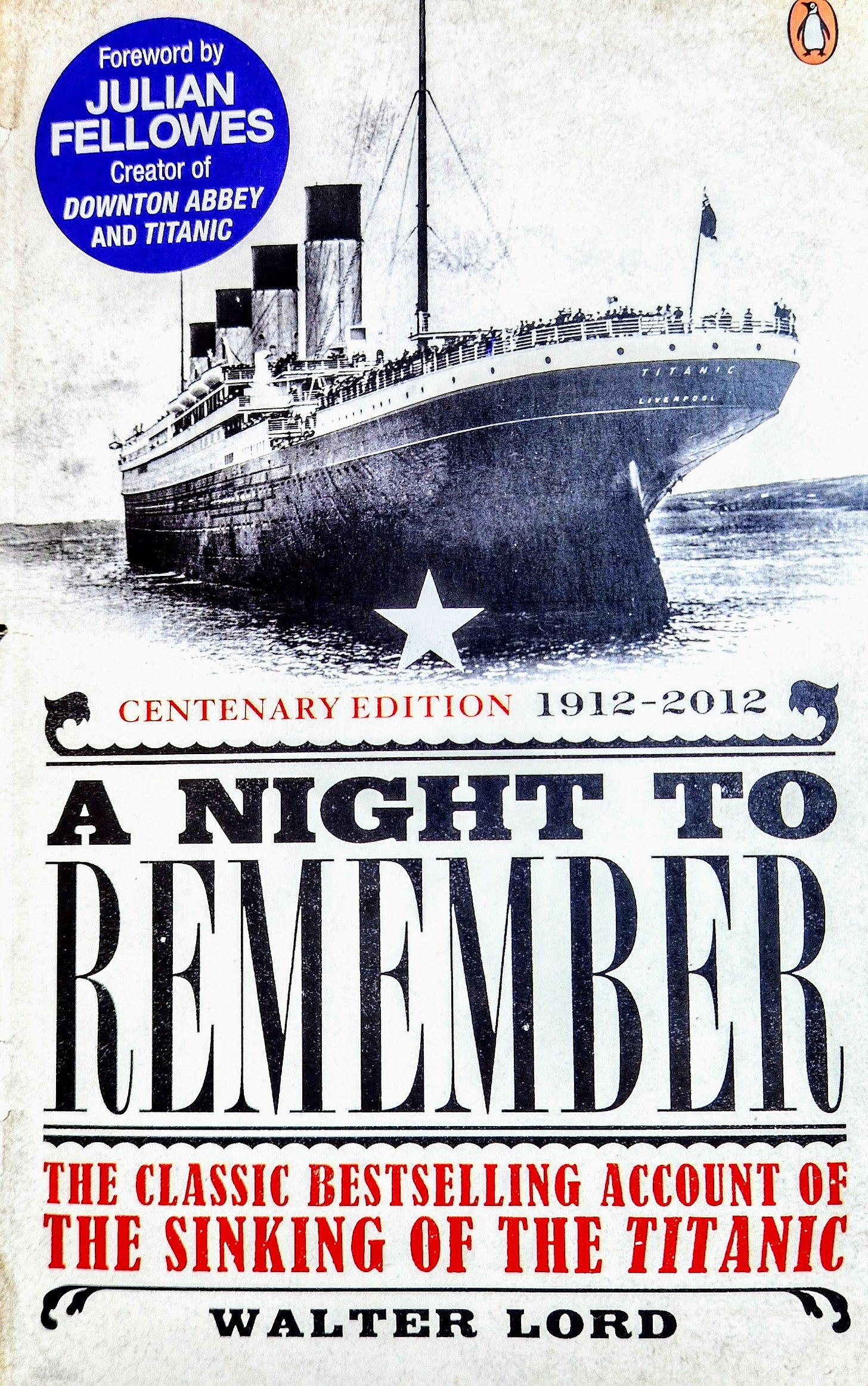

Last month, The Rest is History podcast had a wonderful series on RMS Titanic, from the context of its construction, the make-up of the passengers on-board, the events of the night of 14-15 April 1912 when it sank, and the reaction to the disaster in Britain and the United States. The series sent me back to the Titanic story really for the first time since a minor childhood obsession with it, developed in the aftermath of James Cameron’s film, which, despite the 1990s feeling eternally fixed as a decade ago, was in fact more than a quarter-century ago. The main source for so much of the Titanic story, including the film, is A Night to Remember (1955), by Walter Lord, an American author.

A WELL-TIMED BOOK

In the introduction to the 2012 edition of Lord’s book, released for the centenary of the Titanic disaster, Brian Lavery, the British naval historian who serves as Curator Emeritus at the National Maritime Museum, notes that the status and endurance of A Night to Remember as essentially the canonical text on the subject owes much to it being published at “just the right moment”.

1955 was ten years after the conclusion of the two-part World War that had spanned thirty years. In societies where many men were familiar with the military, having experienced combat and conscription—and with the great cause having been safely won—there was scope to dwell on things other than the nobility and the horror. As Lavery points out, veterans could appreciate films like Private’s Progress (1956), which focused on the absurdities of military service. In the broader population, the decade of memoirs and war films had reached something of a saturation point, and, among the young who had not lived through the war, an active reaction against what they saw as a parental fixation was beginning.1 There was a public appetite for stories of heroism that did not involve the military.

Logistically, Lord wrote when many of those who lived through that night were still around and when enough time had elapsed for survivors’ guilt and other factors to have abated sufficiently that they would talk to him. In writing mostly using witness testimony, Lord told the story from various perspectives, not just from the vantage point of elites, making the book more accessible to a reading public that was becoming truly a mass-audience. In a similar way, the increasingly wide access to television and videos in the 1950s hugely contributed to Lord’s success, making the 1958 movie derived from the book available to a vast audience.

There was some haughty commentary about the book being “popular history”, and what would come to be called “social history”, from traditionalist academics, but if anything this reinforced Lord’s confidence in his project. In responding to criticisms about his methods—specifically Lord’s failure to use the then-new invention of the tape recorder or even to take notes during interviews—Lord’s explanation, that this was to avoid intimidating witnesses reliving traumatic experiences, played into the populist identification with him as a man concerned for those usually ignored by a hidebound Establishment.

That said, while Lord benefited from modernist social trends—the exhaustion with war stories and the spread of Marxist-inflected class resentments—his motives in writing were rather nostalgic, as Lavery explains. Lord loved the old ocean liners, which he had travelled on as a boy, including the Titanic’s sister-ship, Olympic, and Lord’s presentation of the Titanic story appeals to nostalgia openly. Lord was conjuring up, as he writes directly, the “steady, orderly, civilized life” that had existed in 1912, before the disorder of modern life set in and confidence was replaced by uncertainty. “Before the Titanic, all was quiet”, writes Lord. “Afterwards, all was tumult”.2

In the same way, Lord capitalised on technology in both directions, on the advent of mass-ownership of television and on the eclipse of the liners, as airplanes became the more practical means of traversing the Atlantic. Lord was inviting readers to a (by implication, better) world before the latter development.

Subsequent to Lord’s book, there would be two further spikes in interest in the Titanic, the second after the discovery of the wreck in 1985 and the third after Cameron’s film in 1997.3 Both, however, relied on the foundations Lord had set down in the 1950s. In Lavery’s words: without A Night to Remember, “it is likely that the Titanic would be almost forgotten now”.

THE TITANIC STORY

Lord’s book opens with the Titanic look-outs, Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee, spotting the iceberg about half-a-minute before the ship struck it at 23:40 on Sunday, 14 April 1912. The first half of the book is taken up with the drama of the next two-and-a-half hours before the Titanic sinks. Along the way, we meet a large cast of characters, crew and passengers, from first-class to third-class.

One of the key passages in Lord’s book that has endured is his description of the meeting between the Titanic’s architect Thomas Andrews, ship’s Captain Edward Smith, and Bruce Ismay, the managing director of White Star Line, the company that owned the Titanic, after they had conducted a survey below decks, where a three-hundred foot gash has been torn into the starboard side of the hull. Lord writes:

Andrews quietly explained. The Titanic could float with any two of her sixteen watertight compartments flooded. She could float with any three of her first five compartments flooded. She could even float with all of her first four compartments gone. But no matter how they sliced it, she could not float with all of her first five compartments full. The bulkhead between the fifth and sixth compartments went only as high as E Deck. If the first five compartments were flooded, the bow would sink so low that water in the fifth compartment must overflow into the sixth. When this was full, it would overflow into the seventh, and so on. It was a mathematical certainty, pure and simple. There was no way out.

Captain Smith instructs the senior officers to organise an evacuation, famously ordering that it be women and children first.

Lord here explains the crucial difficulty: the absolute priority was to avoid a panic, so there was to be, “No bells or sirens. No general alarm.” The crew would let stand the idea that the Captain was being overly cautious, that loading up the lifeboats was “a matter of form”, as Eloise Smith, a first-class passenger, was told by her husband. But how, then, to convince women who resisted—especially those with children—of the necessity of getting into the lifeboats on such a bitterly cold night, if there was nothing to worry about and everyone would be returning to the ship in a couple of hours? This would be a factor particularly with third-class passengers, who were already the most hesitant about splitting up their (generally larger) families and leaving behind luggage that was in many cases virtually everything they owned, and could not be easily replaced.

As important in how events played out, there was an ambiguity in the Captain’s order: First Officer William Murdoch, the commander of the evacuation on the starboard side, interpreted it to mean women and children first, but allowed men to fill up lifeboat spaces if there were no women and children around, while Second Officer Charles Lightoller on the port side interpreted the order as women and children only, reasoning that to allow any men on the lifeboats before the women and children had departed risked incentivising men to hinder their evacuation, or at worst to start the kind of panicked disorders that were the main thing the crew were trying to avoid. It was Lightoller’s enforcement of this version of the order that led to lifeboats being launched with empty seats, an understandably controversial decision in a predicament where there were only enough lifeboats for 1,178 people, about half of the 2,200 people (1,300 passengers and 900 crew) on board.

Passengers “stood calmly on the boat deck”, Lord writes, and the eight-man band led by the Lincolnshire-born violinist Wallace Hartley assembled to play ragtime music to soothe the crowd. About 00:40 on 15 April 1912, the first lifeboat was launched, on Murdoch’s side. When Lifeboat 5, the second launched, departed a couple of minutes later, also from the starboard, Ismay was trying to help, but was rebuked by Fifth Officer Harold Lowe for getting in the way: at that point, many thought it would be “the most dramatic thing” all evening. Andrews, meanwhile, was “everywhere, helping everyone”, encouraging people into the lifeboats by whatever means he thought best-suited their character: some were corralled by jokes about the need to go through the motions; others were told his honest view that the ship would be underwater in little more than an hour.

The sense of unreality at this time is captured in Lord’s description of Quartermaster George Rowe, who was still on watch at the back of the boat and totally unaware what was happening. Rowe rang the bridge to enquire about the commotion he could see, and only then was it realised “he had been overlooked”: Rowe was told to come at once and “bring some rockets”. Roughly simultaneously, at 00:45, the Titanic became the first ocean liner to send an SOS signal, and the first distress rocket was launched, the beginning of the end of illusions on board that the Titanic was not in serious trouble. There was a vessel close enough to see the rockets, a British steamship, SS Californian, and there was some attempt at contact via Morse light. Tragically, the Californian, which could have rescued everyone, never responded. Lord gives a lot of detail about the missteps that led to this.

The heartbreaking scenes of tremendous bravery, as husbands separated from wives, now began. Walter Douglas, a first-class passenger, a businessman inter alia involved in food—one of his companies became the Archer Daniels Midland Company (ADM)—put his wife in a lifeboat, and when she begged him to join her, responded, “No, I must be a gentleman”. Another American in first-class, Alexander Compton, sharply admonished his mother not to be “foolish” and to get into the lifeboat with his sister: “I’ll look out for myself”.

Eloise Smith vigorously protested leaving her husband, Lucian Smith, an American coal magnate, and she even accosted Captain Smith about it. “Never mind, Captain, about that”, said Lucian, leading his wife away, “I’ll see she gets in the boat”:

Turning to his wife, [Lucian] spoke very slowly: “I never expected to ask you to obey, but this is one time you must. It is only a matter of form to have women and children first. The ship is thoroughly equipped and everyone on her will be saved.” Mrs. Smith asked him if he was being completely truthful. Mr. Smith gave a firm, decisive, “Yes.” So they kissed good-bye, and as the boat dropped to the sea, he called from the deck, “Keep your hands in your pockets; it is very cold weather.”

Mrs. Smith was in Lifeboat 6, launched from the port side at 1:10 by Lightoller, which contained some well-known to 1910s high society, including the American writer and feminist Helen Churchill Candee, and English suffragettes Edith Bowerman and her mother Edith Chibnal, as well as a Denver millionaire socialite, “the unsinkable Molly Brown”, possibly the most famous Titanic passenger even now.

Harvey Collier, a British passenger in second-class, who ran a grocery shop and worked as a verger and bell-ringer at Saint Mary’s Church in Bishopstoke down in Hampshire, had been enticed to emigrate to America by friends reporting back their excellent fortune after establishing a fruit farm in Idaho. At the crucial moment, Lord narrates, Mrs. Collyer had violently resisted efforts by the crew to put her in a lifeboat. Harvey remonstrated with her, “Go, Lottie! For God’s sake, be brave and go! I’ll get a seat in another boat!” He knew, of course, that was not true.

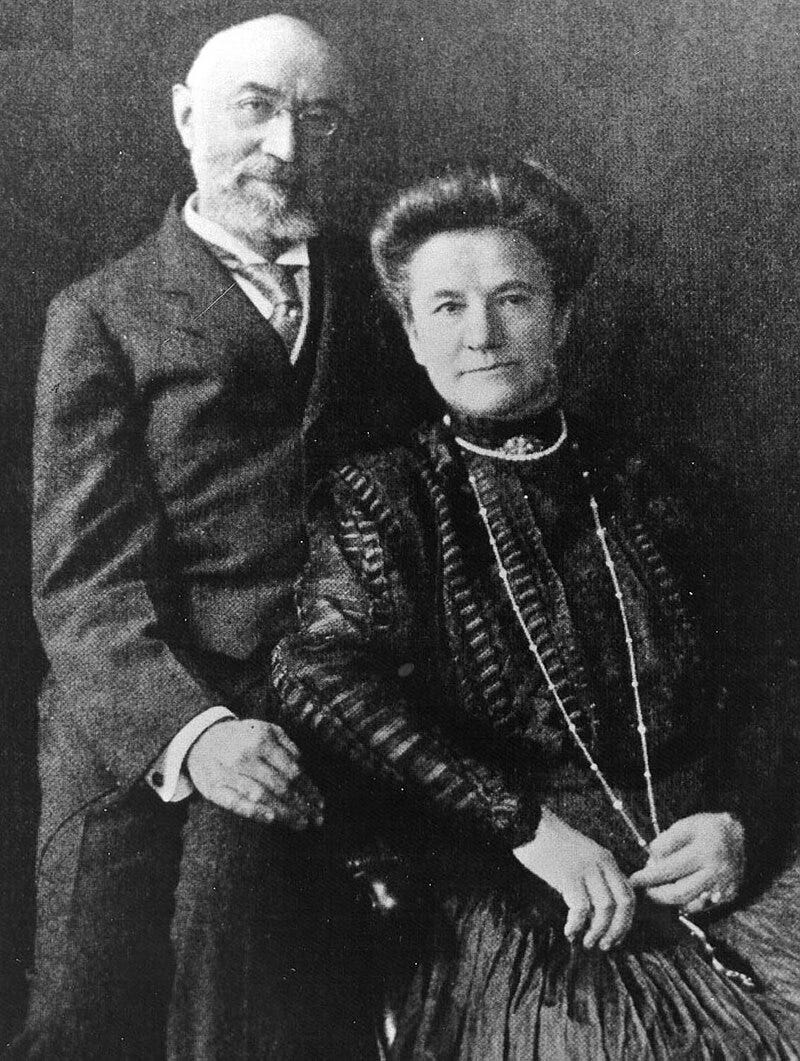

One of the most moving stories was that of Isidor Straus, a 67-year-old German-born American Jew and former member of the U.S. House of Representatives (January 1894 to March 1895), among other things, who was not separated from his wife, Ida. Straus was told, “I’m sure nobody would object to an old gentleman like you getting in”, Lord records, but Straus would not have it: “I will not go before the other men”. Hearing this, Ida Straus got out of a lifeboat and rejected Isidor’s efforts to persuade her to get back in. “We have lived together for many years”, said Ida. “Where you go, I go.” (Isa gave her place to one of her maids and gave the maid her coat, telling her, “You’re going to need this more than I will.”) The Strauses “then … sat down together on a pair of deck chairs”, Lord writes, and waited for the end. The heroism of Straus, in particular, was to become important to American Jewry, battling at that time against stereotypes that Jews were unmartial and somewhat cowardly.4

Millionaire Benjamin Guggenheim, another American Jewish businessman of German descent, was not on board with his wife, but a lady of doubtless similar distinction, a 25-year-old singer from Paris named Léontine Aubart. When the crunch came, however, it was to Mrs. Guggenheim that thoughts turned: “Guggenheim had a … message [he passed to a steward]: ‘If anything should happen to me, tell my wife I’ve done my best in doing my duty.’ … [H]e and his valet [Victor Giglio] now stood resplendent in evening clothes. ‘We’ve dressed in our best,’ he explained, ‘and are prepared to go down like gentlemen’.” The steward Guggenheim gave the message to, James Etches, later testified that Guggenheim had been very helpful in getting others into the boats.

“It was all so urgent—and yet so calm”, Lord notes of this part of the night. All the same, just before 1:00, Chief Officer Henry Wilde asked Lightoller where the firearms were kept. Lightoller led Wilde, Captain Smith, and Murdoch to the locker containing the weapons. Wilde pressed a pistol into Lightoller’s hand, saying: “You may need it”. Murdoch was given one, too, a detail to which we will return. The evidence does point to some disorder shortly thereafter.

An anecdote not included in Lord’s book is one of the last reasonably certain sightings of Captain Smith, during the lowering of Lifeboat 8, which launched from the port side at 1:00. With some of the men getting a bit rowdy and pushing forward towards the boat, Smith bellowed: “Behave yourselves like men! Look at all of these women [inclining towards Lifeboat 8]. See how splendid they are. Can’t you behave like men?”5 It worked and everything settled down, at least for half-hour or so.

A story Lord does include is that Lowe, the Welsh officer commanding Lifeboat 14, launched at 1:25 on the port side, fired shots in the air and threatened to shoot a young man who tried to stowaway on the boat. The man got back on the Titanic, and the men simmered down, but by the time Murdoch was launching Lifeboat 15 at 1:41 he was having to brandish his firearm and shout: “Stand back! Stand back! It’s women first.” There can be no doubt that panic was spreading by this time, but these serious efforts by men to force their way onto the lifeboats do seem to have been reasonably small-scale and isolated. Lord reports that, to the end, more than a dozen “first-class men worked with the crew, loading the last boats”, for example.

The last of the sixteen main lifeboats was launched at 1:50 and by 2:05 two of the smaller collapsible boats had been launched, the last of them with Ismay in. The crew was still struggling with the two collapsibles when the ship went down; washed into the sea, they would ultimately save a number of lives.

Another iconic scene usually included in retellings of the Titanic story is the last sighting of Andrews, and that originates with Lord:

The smoking room was not completely empty. When a steward looked in at 2:10, he was surprised to see Thomas Andrews standing all alone in the room. Andrews’ life belt lay carelessly across the green cloth top of a card table. His arms were folded over his chest; his look was stunned; all his drive and energy were gone. A moment of awed silence, and the steward timidly broke in: “Aren’t you going to have a try for it, Mr. Andrews?” There was no answer, not even a trace that he heard. The builder of the Titanic merely stared aft. On the mahogany-panelled wall facing him hung a large painting called ‘The Approach of the New World’.

Outside the smoking room, on the deck, “the band still played”, writes Lord. This is probably the most iconic part of the Titanic story—the detail, along with women-and-children-first, known to everybody. By this point, the band had switched from ragtime to hymns. In our cynical times, it is easy to be derisive about this—the very phrase “and the band played on” has become a way to dismiss something as futile—but those eight men really did play on to the very end that night, making no attempt to save themselves so they could provide some small comfort to other people facing imminent death.

With the bow submerged around 2:10, the stern was lifted out of the water. As people on deck were no longer able to stand without grabbing onto something, the band was finally silent. The electrics also gave way at this time, leaving only the moonlight. And then the first funnel collapsed, toppling into the water and killing God-knows how many people.

Ironically, the funnel collapse saved Lightoller’s life, in two senses. Seeing that the game was up, Lightoller jumped overboard just before the funnel fell, but he got trapped by the suction against some grating and it seemed he would drown there, but the impact of the funnel shook loose an air bubble that pushed him to the surface. According to Lord, the splash of the funnel had also thrown Collapsible Boat B far enough from the Titanic that it was not dragged down with the ship, and made it distant enough from the desperate mass of people in the water that it was not overwhelmed. Two-dozen men made it to Collapsible B, which, though upturned, provided safety from the freezing water. Lightoller directed the men for three hours in adjusting their weight and so on to prevent the boat going under.

The uneasy situation of the Titanic, with its stern in the air, was ended at 2:17. The hull broke in two, and the falling stern killed many more people. As the front half sank beneath the waves, it pulled the back perpendicular in the water. The front then broke clean away and plummeted to the seabed. The stern remained floating for about thirty seconds, before sinking straight down at high speed at 2:20.

The temperature in the Atlantic Ocean was minus two degrees Celsius. Most people in the water were dead from hypothermia within twenty minutes. One lifeboat went back, Number 14 commanded by Lowe, after transferring its passengers to other lifeboats. But, as Lord outlines, a horrible calculation had to be made about when: “Lowe waited for the swimmers to thin out enough to make the expedition safe”. As Lowe later told the U.S. Senate investigative committee, he delayed until the screams in the water had “quieted down”: “It would not have been wise or safe for me to have gone there before, because the whole lot of us would have been swamped and then nobody would have been saved.” Lowe’s logic was not controversial at the moment: Molly Brown’s attempted mutiny to have Lifeboat 6 go back is remembered precisely because it was so exceptional. Even so, just four people were pulled out of the water, one of whom soon died,6 and Lord argues that Howe misjudged how long the journey back to the people in the water took, so his arrival after 3:00 was later than intended and he saved fewer people than he might have.

When it was all over, about 700 people (500 passengers and 200 crewmen) were saved and 1,500 people (800 passengers and 700 crewmen) were dead.

The second half of Lord’s book is taken up with the aftermath. The waiting in the lifeboats, where frayed nerves led to some bickering. The arrival of RMS Carpathia—the only ship to respond to the Titanic’s distress call—at the site of the sinking at 4:00. The process of transferring people from the lifeboats to the Carpathia, and the belated arrival of the Californian. The end of the search for survivors and Carpathia Captain Arthur Rostron asking Ismay if they should hold a Christian service before leaving. Ismay “agreed”: he was so shell-shocked and full of opiates at that point, “anything Rostron wanted was all right with him”. It is here that there occurs possibly the most arresting line in Lord’s book: “While they murmured their prayers, the Carpathia steamed slowly over the Titanic’s grave.”

Lord documents the way the early press coverage—saying there had been no casualties—soon gave way to sheer fantasy as the rumour-mill made clear there had been some casualties, but, as “Rostron had no truck with newsmen” and kept the Carpathia’s communications strictly for official work and messages to the families of Titanic survivors, there was no confirmation of the scale of the disaster until the Carpathia arrived in New York about 21:30 on Thursday, 18 April 1912. Lord makes only sporadic references to the post-disaster investigations in Britain and America,7 and the reforms implemented, including diverting ocean traffic to the south, out of the ice fields, and the requirement to carry enough lifeboats for everybody on board.8

A NIGHT TO REMEMBER SEVEN DECADES ON

A Night to Remember is quite a strange book. Part of this is doubtless because it is an early example of social history in the modern sense, which would come into vogue properly in the 1960s and has matured in the decades since.9 Thus, Lord had no model to work from, probably explaining the slightly odd pacing and structure, though there is no doubt the book synthesises the various viewpoints it is told from remarkably smoothly and it is an easy read.

Where the book is open to criticism is as a work of history. An obvious problem is that there are no footnotes, making verification difficult. The lack of interview recordings or contemporaneous notes meant Lord had no transcripts or summaries that could have been referred to anyway. This is part of a broader problem of Lord’s handling of sources. It is not that Lord is slipshod with facts, exactly—in a strict sense, his errors (names, dates, etc.) are few and minor—but his deployment of facts is, well, strange.

In some cases, Lord will skate over some notoriously contested incident without even flagging up that it is contested. It is understandable that in a narrative or popular history, an author will make choices and tell the story they find most plausible. This is what a reader of such works wants and disrupting the flow with “on the one hand, on the other” every few sentences derails the project. It can even be added that sometimes narrative historiography is a better way of getting at the truth than the more academic style.10 One way to square this circle would be to elucidate the controversies in footnotes where Lord explained why he comes down where he does, allowing those readers with a deeper interest make up their own minds. Maddeningly, however, in other cases, where Lord takes the opposite route and does show his working, he makes it apparent from his own evidence that the conclusion he has reached is unlikely to be the correct one.

A couple of examples:

Several eyewitnesses on the Titanic reported that First Officer Murdoch, during the closing scenes after 2:00, shot himself, possibly after shooting several men trying to storm one of the collapsible lifeboats. Second Officer Lightoller said this was untrue. There is, though, good evidence to suggest somebody in the crew shot themselves shortly before the end, and, unlike the disinterested passengers who identified Murdoch, Lightoller had a clear motive to spare Murdoch’s widow any further pain by saying her husband was swept out to sea, rather than committed suicide. So, a very murky episode. Lord deals with this by referring to “First Officer Murdoch committing suicide” in a list of “engaging tales born these first few days” after the disaster. Lord is completely correct that “legends” began to grow around the Titanic immediately after she sank, and that many of these could be traced back to passengers speaking to the press—either giving over-excitable accounts or having their words rendered as such by the journalists in search of good copy. But the Murdoch story is more complicated than that and should not have been grouped in with, for example, the various dubious accounts of Captain Smith’s last moments.

Or take the story about Andrews being seen “stunned” in the smoking room at 2:10. From Lord’s account, one would have no inkling that there was any contest here, and the scene shows up again and again in cinematic representations of the Titanic tragedy. However, Lord reports this story from “a steward”, and once the reader knows that steward was John Stewart,11 and that Stewart probably departed on Lifeboat 15,12 which launched at 1:41, questions have to be asked, especially when Stewart’s account is set against that of multiple other survivors attesting to seeing Andrews on the deck, continuing to load people onto boats up to the last.13 There is a way of reconciling Stewart’s version of events with the other evidence, if he was wrong about the timing. Stewart could have seen Andrews earlier, taking a break, and in fact it does not seem Stewart directly mentioned a time. The other obvious answer is that Stewart invented the story. A further option is that Lord had good reason to think Stewart saw Andrews at 2:10: he really should have explained why, if so.

There is also an issue with another Andrews story told by Lord: when Andrews tells Captain Smith and Ismay that it is a “mathematical certainty” the ship will sink in at most two hours. Admittedly, that phrase is not in quotation marks in Lord’s account, but it has been in virtually every representation ever since, including as part of one of the best scenes in the 1997 film. Here, the issue really is more a straightforward abuse of sources. The glaring problem is that Andrews and Smith were dead, as was Ismay by the time Lord was researching. So where did this story come from? Lord does not say. One critic of Lord’s noted that he had a tendency to connect “his patchwork of countless testimonies by means of fictitious little scenes and dialogues”.14 What has made the story stick is that it is so dramatic, and that a meeting of this kind must have taken place, but, rather than explain the inferential evidence for what was said, Lord constructs a novelistic scene.

The last song played by the band is generally agreed to have been, “Nearer, My God, To Thee”. As Lord notes, “many survivors” testify to this, and “there’s no reason to doubt their sincerity”. Yet in the book, Lord writes flatly that “Autumn” was playing as the Titanic entered her death throes, and in his final chapter—‘Facts About the Titanic’—Lord explains that this claim came from Junior Wireless Operator Harold Bride, whose account “somehow stands out”. There are arguments Lord could have made against the consensus,15 but it is just weird to rest his verdict on an unexplained preference for the story of single witness who is contradicted by so many others.

Lord concludes the book with a myth-busting section, but within it he gives credence to one of the enduring myths: that a man dressed as a woman in order to escape. Lord even names him: Daniel Buckley, an Irishman in third class. The myth in Lord’s telling is that the cross-dressing culprit was one of the prominent men of the day from first-class. Reversing some of the bottom-up class warfare Lord has waged earlier in the book, he finishes by waging it from the top-down: “He was only a poor, frightened Irish lad, and nobody was interested.” The reality is that Buckley did jump into a lifeboat and a kindly lady hid him under some clothing—and Lord says so! But Lord does not seem to see a distinction between Buckley having “freely acknowledged that he wore a woman’s shawl over his head” to hide from the crew, and the legend of a man dressing as a woman to waltz past Lightoller or Murdoch. Again, many readers will immediately spot that Lord’s evidence contradicts Lord’s claim.

The very last paragraph of Lord’s book reads:

The answer to all these Titanic riddles will never be known for certain. The best that can be done is to weigh the evidence carefully and give an honest opinion. Some will still disagree, and they may be right. It is a rash man indeed who would set himself up as final arbiter on all that happened the incredible night the Titanic went down.

Fair enough—in principle. It just feels like a bit of a cop-out after what Lord does in practice.

On the point of myths, if one, so to say, pulls the camera back a bit, and examines not the details in A Night to Remember, but some of the broader narrative themes, Lord really does start to look more like a purveyor of myths than a foe. Two very tenacious myths about the Titanic are that Ismay behaved contemptibly on board that night, and that gross discrimination against third-class passengers was responsible for dooming so many of them.

Lord, to his credit, does not recycle the myth—which appears in Cameron’s film—that Ismay was responsible for the crash by pushing Captain Smith to break speed-limits to grab headlines by arriving in New York early, and Lord is generally less polemical about Ismay than motion-picture adaptations—including of Lord’s own book—would be. But Lord does sow the seeds. Ismay is described as a chameleon, playing at being crewman and passenger, depending on what benefited him more at any moment. Having taken on the mantle of crewman to help load the boats, Lord writes, “Then came another switch. At the very last moment [Ismay] suddenly climbed into [Collapsible] Boat C.” It was this act of self-preservation for which Ismay would never be forgiven in his own time; it compared too unfavourably with the stories of the Strauses and Guggenheim and Captain Smith bravely going down with the ship, and the sense Ismay had taken advantage of his position as director only made it worse.16 Lord at least does not imply that Ismay killed somebody else by taking that seat. As is pointed out in The Rest is History series, which deals very well with the reputational assault on Ismay, there were six empty places in that lifeboat. The other little x-factors that always make Ismay such a wretched figure on stage and screen—his carpet slippers and dithering on the Carpathia—are included, though.

Lord gets himself quite heated about the treatment of third-class passengers, noting that the gates from third-class up to the deck were not opened until 00:30 and arguing the crew left them to fend for themselves. “No one seemed to care about third class”, Lord declares. Superficially, this can seem to be confirmed in the fatality figures:

When the statistics are broken out a bit further, however, what becomes clear is that the overwhelming dividing line in who lived and died was sex, not class. 74% of female passengers on the Titanic and 51% of children survived; only 18% of the men did.17 More third-class women, absolutely and relatively, survived than first-class men.

There were problems in getting third-class passengers to the lifeboats, but these were not wilfully inflicted by the White Star crew. Lord omits to mention that the very existence of the gates separating all classes of passengers from each other were not a White Star imposition; they were a disease-control regulation imposed by U.S. immigration. Nor was the fifty-minute delay in opening the third-class gates deliberate discrimination: it was an oversight in a moment of crisis. The gates were open before the first lifeboat was launched—before the crew remembered to inform one of their own, Quartermaster Rowe, about what was happening, if it comes to that—and many of the factors that hindered the third-class passengers’ escape arose from the features and values of the third-class passengers themselves, as Lord explains in some detail, making his high dudgeon about the neglect of the third-class passengers all the more bizarre.

As Lord documents: the biggest single issue was that the third-class quarters were simply furthest away from the deck; third-class passengers did get lost in the maze of the corridors, though efforts by the crew to guide them—and to fetch people from their rooms—ameliorated this; and the resistance of third-class women to taking often young children out in the boats was particularly acute, partly because they were wary of separating from older male children (of whom they tended to have more) and their husbands, partly because many third-class passengers did not speak English. This was an especial problem in the earlier phase, when the crew’s message was that getting into the lifeboats was out of an abundance of caution. The language barrier was bad enough; add in mixed messages and cultural differences that meant non-verbal cues were more difficult to pick up, and it created a serious problem. There are many stories—Lord records some of them—of third-class passengers getting to the deck, then going back inside because of the cold or because they came to understand they were expected to leave without family members.

Where Lord most emphatically succeeds, perhaps unsurprisingly given his personal history and motives in writing the book, is in summoning up the “lost world” where the Titanic was built and sank. There were the prejudices of that world: on both sides of the Atlantic, the commentary was unanimous that the Anglo-Saxon race had come out of this very well,18 often with remarks explicitly drawing out the implication that other races would have handled things less well, and the demanding cultural expectations damned men like Ismay. For the subjects of the British Empire nothing—absolutely nothing—could capture and hold public imagination like a really solid heroic catastrophe. Captain Robert Scott, in failing nobly and perishing in the Antarctic—just two weeks before the Titanic went down, incidentally—was immortalised in British memory in a way the successful Edmund Hillary could never hope to be,19 and this dynamic held when it came to the military.20 Unembarrassed talk about (white) “race” in the Anglosphere had been buried under the rubble in 1945, and good riddance:

But along with the prejudices, some nobler instincts also were lost [from the time of the Titanic]. Men would go on being brave, but never again would they be brave in quite the same way. These men on the Titanic had a touch—there was something about Ben Guggenheim changing to evening dress, about Howard Case flicking his cigarette as he waved to Mrs. Graham … Today nobody could carry off these little gestures of chivalry, but they did that night.

An air of noblesse oblige has vanished too. … Overriding everything else, the Titanic also marked the end of a general feeling of confidence. … For 100 years the Western world had been at peace. For 100 years technology had steadily improved. For 100 years the benefits of peace and industry seemed to be filtering satisfactorily through society. In retrospect, there may seem less grounds for confidence, but at the time most articulate people felt life was all right. … Never again would they be quite so sure of themselves.

In technology especially, the disaster was a terrible blow. … But it went beyond that. If this supreme achievement was so terribly fragile, what about everything else? If wealth meant so little on this cold April night, did it mean so much the rest of the year? Scores of ministers preached that the Titanic was a heaven-sent lesson to awaken people from their complacency, to punish them for top-heavy faith in material progress. If it was a lesson, it worked—people have never been sure of anything since. The unending sequence of disillusionment that has followed can’t be blamed on the Titanic, but she was the first jar. … That is why, to anybody who lived at the time, the Titanic more than any other single event marks the end of the old days, and the beginning of a new, uneasy era.

From the moment it happened, the story of the sinking of the Titanic became a metaphor, a canvas on which people projected their moral and political predispositions: it served equally the clergymen hostile to the hubris and greed of modern industry, and the patriotic poets “comparing Anglo-Saxon sangfroid with the excitable gibberings of lesser breeds”.21 Lord does not go in for any of this, and it is one of the strongest aspects of the book. As set out above, Lord renders moral judgments about players involved in the Titanic story, but the book is a chronicle of events: Lord does not engage in a search for “meaning” in the actual story, as so many have.

What Lord does do is another venerable tradition in Titanic historiography: to present the sinking as the closing of a chapter of history. What makes Lord unusual is drawing the line between the old world and the new so sharply around the Titanic disaster itself—as marking that divide “more than any other single event”. The more common tendency, in both historiography and popular memory, is to see the Titanic sinking as a harbinger of the First World War, which began two years later, tore apart the world of the Long Nineteenth Century, and ushered in a conflict that did not really end until the Soviet Union was dissolved in 1991. The Great War is neither mentioned nor alluded to in A Night to Remember. While Lord might be mistaken about the exact timeline—an author can be forgiven for over-hyping his subject—he is nonetheless onto something in seeing the Titanic disaster as an instructive window onto a world that did not know it was deep into twilight.

The Titanic story allows one to see what the civilisation of the early 1910s Anglosphere looked like when “tested to its foundations”, as Winston Churchill remarked at the time.22 Humans facing death are creatures stripped to their core: what really matters to them, what they really believe, is on show at such a moment. And in 1912, the answer for Britons and Americans was duty, honour, authority, and self-restraint. This was a world where the archetypes of Great Men shaped the moral imagination of millions, and the quest for Imperial glory was coupled with an understanding of the responsibilities that imposed on them. All men knew the code they were expected to follow and most of them were determined to abide by it. The women-and-children-first order was mere fortification: it was the path of least social resistance to die honourably, to smile as the lifeboats sailed away and maintain equanimity as the end approached. Underwriting it all was a profound Christian certitude, in the duties the powerful owed to those who were weaker and in the life to come. Some will find the thought of such a world unsettling, even repellent; others will mourn its passing. In either case, Lord was right about what it was, and that it has gone.

REFERENCES

This dynamic was even more obvious a decade later. A significant element of the Sixties “counter-culture”—very much including the “anti-war” movement—was a literally childish rebellion, a reaction from the Baby Boomers who grew up in the 1950s against the world of their parents, which “the war” had physically conditioned and socially structured as homogenous and staid. The Second World War also continued to play a domineering role in private conversation and political debate. The Suez enterprise in 1956, for example, was justified by Prime Minister Anthony Eden as an application of the wartime lessons—pre-empting the rise of an Arab Hitler in the form of Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser. Many people in their early twenties by the 1960s were simply sick of hearing about the war, and this became a theme from the icons of “youth culture” in the era, notably from music bands like The Beatles. See: Patrick Dillon (2011), The Story of Britain from the Norman Conquest to the European Union, p. 329.

It is always easy to sneer at nostalgic presentations. It can be (fairly) pointed out that in the United States in 1912, the country was racked by horrendously violent labour relations and the situation for black Americans was entering its post-Reconstruction nadir, and in Britain there was major social turbulence from the Suffragettes and the Home Rule crisis in Ireland, both of which eventuated in domestic terrorism and the latter of which might have pushed the country into civil war. It is also true that in 1955, especially in America, there was more wealth, more equally distributed, than ever before, but this was accompanied by the devastation of two global conflicts, the Soviet nuclear threat overhanging everything, the enslavement of half of Europe and much of Asia, worldwide Communist subversion, and the crumbling of the Christian moral consensus. It is not difficult to see why so many people, if offered the choice, would have preferred the problems of 1912 to the problems of 1955.

One might argue for a fourth spike in “Titanicmania” in 2012, judging by the quantity of books produced for the centenary.

American rabbi Dr. Samuel Schulman said: “Isidor Straus … was a man with a great intellect, a sensitive conscience, a great heart, a loyal son of his people, and a loyal American—a great man. … Isidor Straus was a great Jew. … In the past we, as Jews, have been able to say the Jews are great philanthropists. Now when we are asked, ‘Can a Jew die bravely?’ there is an answer written in the annals of time.”

Judith B. Geller (1998), Titanic: Women and Children First, p. 41. Unfortunately, the story—which is reflected in the inscription on Captain Smith’s tombstone—that he restored order by shouting, “Be British, boys. Be British!”, does not seem to be true.

Four is the figure Lord gives for the men rescued from the sea by Lifeboat 14, and this number is often repeated. Three of the men are known for certain: William Hoyt, an American in first-class, who died soon afterwards; a Chinese passenger from third-class (Lord mistakenly says “a Japanese steerage passenger”), Fang Lang, who (Lord is right about this) “had lashed himself to a door”, the inspiration for how “Rose” (Kate Winslet) survives in the 1997 film; and Harold Phillimore, a Briton in second-class. (Lord also makes an error in naming the third man as steward John Stewart.) There is uncertainty about who—or whether—there was a fourth man rescued by Lifeboat 14. Some accounts remember only three; some suggest it was four, but two of them died. The latter is not implausible. Hoyt’s prominence—in every sense: he was a very large gentleman—ensured that he was recognised. It is conceivable someone from second- or third-class who was pulled aboard and perished would have joined the nameless fatalities. The records outside first-class are such that we still cannot be sure exactly how many passengers were on the Titanic, let alone identify them all.

Lord mentions perhaps the most infamous exchange in the American investigation, where Senator William Alden Smith, a Republican from Michigan, asked, “Do you know what an iceberg is composed of?” And Lowe replied: “Ice, I suppose, sir”. Lord correctly fixes on this moment as representative of the Senate’s conduct, but bizarrely seems to take it as evidence of the Senate’s thoroughness, rather than a demonstration that the U.S. “inquiry” was a grandstanding exercise of sheer populism and demagogy. The issue might be one of simple national pride, because Lord presents the British investigation—whose findings about the disaster and recommendations for reform have held up rather well—as a whitewash.

The regulations on lifeboats were first tested with RMS Empress of Ireland, a British-built, Canadian-operated ship that was struck in thick fog on 29 May 1914 at the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River in Canada by the SS Storstad, a Norwegian collier (bulk ship). The Empress of Ireland had nearly 1,500 people on board (420 crew and 1,057 passengers) when it was hit, and there was lifeboat space for every one of them, but there was no time to load them as the ship foundered in fourteen minutes. 1,012 people died. The British investigation into the Empress of Ireland was led by Viscount Mersey, John Bigham, who had led the British Titanic investigation and would later lead the inquiry after a German submarine sank the RMS Lusitania on 7 May 1915, killing 1,200 people. (The Storstad was also destroyed by a German U-boat during the Great War, torpedoed in the Atlantic, fifty miles off the southern coast of Ireland, on 8 March 1917.)

Tangential, but a really superb recent example of social history is The Restless Republic: Britain Without a Crown (2022), by Anna Keay.

An example of a book where writing a narrative history was superior to the academic alternative was Tom Holland’s In the Shadow of the Sword (2012) about the origins of Islam. The format, telling the story of how the world of Late Antiquity became the world of Islam, meant there was no way to hide knotty issues behind a smokescreen of source criticism and general academese: Holland gives the reader his best assessment of what was happening at each juncture, flagging up in the text where the evidence is particularly complicated or thin, and documenting in the endnotes the contours of (and the participants in) the debates on other matters, so the reader can go off on their own to dig into these issues.

Shan Bullock (2012), Thomas Andrews: Shipbuilder of the Titanic: Centenary Edition, p. 9.

W. B. Bartlett (2010), Titanic: 9 Hours to Hell: The Survivors’ Story, p. 53.

“ … on the Boat Deck, Thomas Andrews was still hard at work. At around 2:10 a.m., well after Stewart had seen him during his quiet moment of reflection in the First Class Smoking Lounge, he was sighted tossing deck chairs overboard to aid the ‘unfortunates’ who were likely to end up struggling in the water. He was next spied carrying a lifebelt, apparently on his way to the Bridge.” See: Tad Fitch, Bill Wormstedt, J. Kent Layton (2012), On a Sea of Glass: The Life and Loss of the RMS Titanic.

Linda Maria Koldau (2012), The Titanic on Film: Myth versus Truth, p. 24.

It is reported that passengers sang “Nearer, My God, To Thee” as the steamer SS Valencia sank in January 1906 off British Columbia. Some of the Titanic passengers must have known about this: one can see a plausible argument that the Valencia story has blurred with confused memories amid the stress of that night in 1912.

The other prominent man to was suffer reputationally as Ismay did was Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon, an internationally famous fencer, who, along with his wife, Lucy, a lingerie tycoon, boarded Lifeboat 1, launched at 1:05 AM by Murdoch. Like Ismay, the general sense that Duff-Gordon had let the side down was added to by further stories that made the unarguable fact that he had lived seem even worse. In Duff-Gordon’s case, there was the fact the lifeboat had only twelve people in it and had a capacity of forty. The reason for this was nothing to do with Duff-Gordon: Murdoch was trying to get this small lifeboat away to clear space for the larger ones behind it. And then there was the accusation that Duff-Gordon had paid a bribe to save himself, which was a garbled misunderstanding of Duff-Gordon having given each of the crewmen on Lifeboat 1 £5 (£715 in today’s money). As Lord explains, this had come about when Duff-Gordon was talking to a fellow passenger about losing his property aboard the Titanic, but being able to replace it easily, and one of the crewmen had tetchily remarked something to the effect of, ‘Alright for some’. Duff-Gordon thereupon said he would pay each of them £5 so they could replace the belongings and equipment they had lost on the ship.

Absolute figures are: 296 out of 402 women survived (74%); 56 out of 109 children (51%); and 146 out of 805 men (18%).

Immediately after the Titanic disaster, Winston Churchill, then-First Lord of the Admiralty, neatly encapsulated British public opinion in a letter to his wife, Clementine, who was convalescing in Paris: “I cannot help feeling proud of our race and its traditions as proved by this event. Boatloads of women and children tossing on the sea safe and sound—and the rest, silence. Honour to their memory. In spite of all the inequalities and artificialities of our modern life, at the bottom—tested to its foundations, our civilisation is humane, Christian, and absolutely democratic. How differently Imperial Rome or Ancient Greece would have settled the problem. The swells and potentates would have gone off with their concubines and pet slaves and soldier guards, and … whoever could bribe the crew would have had the preference and the rest could go to hell. But such ethics could neither build Titanics with science nor lose them with honour.” See: Andrew Roberts (2018), Churchill: Walking with Destiny, p. 166.

Hillary was, of course, a New Zealander, but that technicality got rather lost in the celebratory British coverage of his conquest of Everest in 1953.

In 1941, in ‘England Your England’, a brilliant essay on the British character, George Orwell wrote that for foreigners British anti-militarism looked like “sheer hypocrisy”, given that the British had “absorbed a quarter of the earth and held on to it by means of a huge navy”. Of course this was hypocrisy. At the same time, the British dislike of standing armies was quite genuine and a “sound instinct. A navy employs comparatively few people, and it is an external weapon which cannot affect home politics directly.” There must have been officers in the British army who longed to rule a junta, but there were less of them and the British would not stand for swaggering antics from men in uniform: a British military parade is a “formalised walk” and if anyone tried goose-stepping “people in the street would laugh”.

Orwell went on: “In England all the boasting and flag-wagging, the ‘Rule Britannia’ stuff, is done by small minorities. The patriotism of the common people is not vocal or even conscious. They do not retain among their historical memories the name of a single military victory. English literature, like other literatures, is full of battle-poems, but it is worth noticing that the ones that have won for themselves a kind of popularity are always a tale of disasters and retreats. There is no popular poem about Trafalgar or Waterloo, for instance. … The most stirring battle-poem in English is about a brigade of cavalry which charged in the wrong direction.”

Orwell was referring to Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s, “The Charge of the Light Brigade”, about the October 1854 battle in the Crimean War—and he was perfectly correct that more British hearts were stirred by this fiasco than ever gave a damn about the acquisition of India. Before that, in 1842, there had been the retreat from Kabul, which provoked a similar reaction, and later, in 1885, the murder of General Charles Gordon in Khartoum by the Mahdists became the most sensational public cause—one of the few times the British population remembered they had an Empire. These were what moved the British, and it is what damned Ismay in British eyes: he had refused to play the part of General Gordon, willingly dying honourably at his post. The exceptions—the popularly celebrated British victories, over the Spanish Armada and the Nazis—prove the rule: these were defensive triumphs over the odds on the knife-edge of national extinction. And even here a qualification is needed about the Anti-Nazi War: the most celebrated episode of that combat to this day is the Dunkirk evacuation in 1940, a strategic calamity that saw Britain thrown off the European Continent and left vulnerable to a Nazi invasion—all of which only bolsters the heroic memory of the “little ships” that rescued British soldiers from the jaws of the Nazi war machine.

It is interesting that there is a direct link between the Titanic and Dunkirk: Lightoller sailed in his personal yacht, the Sundowner, over to France to recover British servicemen.

The phrase is Tom Holland’s, excellently summing up on The Rest is History (22:25) how much of the British and American press reacted to the loss of the Titanic.

Roberts, Churchill, p. 166.