Did the Qur’an Exist Before Muhammad?

The most basic questions about the Qur’an’s origins remain contested. Where and when the Qur’an comes from, how it was formulated, when and how it was first written down, even what language it was in: nobody knows.1 As to who conceived and/or compiled it, if the Qur’an text is viewed on its own terms, liberated from the weight of an Islamic Tradition that dates at the earliest from the late eighth century—150 and more years after the Ishmaelite Arabs overran Byzantium’s eastern provinces and conquered Persia—one would scarcely know it was related to someone called Muhammad at all.2

The date of Qur’anic codification—when it was arranged into the extant Book—is of particular salience because such a context would constrain the possible answers to other questions. To simplify massively, Qur’an scholars divide into two camps.

First, there are those who believe there was a “Ur-Qur’an” produced in some form during Muhammad’s mission (c. 610-32/4), which was the basis for the variant editions that circulated for a relatively brief time thereafter, before the text was stabilised and a uniform recension imposed.3 The Tradition itself tells of seven ahruf (forms) in use until 653 AD, when the Caliph Uthman settled on one standard version and burned the rest.4

Second, there are those—notably John Wansbrough—who believe the search for a “Ur-Qur’an” is pointless because there never was one: the “canonical” Qur’an was synthesised from disparate materials in “the community” as part of the great exegetical project of the ninth century in Abbasid Baghdad.

The scholarly consensus favours the early-codification theory at the present time, but the Wansbrough thesis retains adherents,5 and in any case consensus does not mean much in Qur’anic Studies: the field is working with such bare shreds of evidence that many of the current theories for the Qur’an’s origins have no scholarly adherents beyond the scholar who came up with them, and when there was a broad consensus, before the 1970s, it was a false consensus that put too much weight on the Tradition.6 Moreover, the strongest hard evidence against Wansbrough’s position presents significant challenges to the early-codification school, too.

It is clear that material much older than Muhammad is woven throughout the Qur’an.

Take the reprobated “people of the trench” (or “ditch” or “pit”), who reportedly burned “believers” in a “trench” and were consigned to Hell as punishment (Sura 85:4-10). The meaning of this has led to much debate. One line of analysis seeks to map this episode onto historical events. A leading contender is the massacre of Christians at Najran in the early sixth century by the ruler of the Jewish Himyar Kingdom in what is now Yemen. But it is equally as likely this explanation is a case of, so to say, right church, wrong pew—that there was enough memory to identify the Jewish element, but not enough to remember how it fit in.

The “Dead Sea Scrolls”, a collection of enigmatic Jewish manuscripts of a kind that appeared from time to time in the wilderness beyond the Land of Israel, described Hell as “the Trench”, to whose fires the damned were consigned at the End of Days. Is this ayat in Sura al-Buruj drawing on the Dead Sea Scrolls? It is possible from the timeline. The Scrolls—according to the carbon dating—were written between 351 and 203 BC. But whether their journey between that time and their rediscovery in the 1940s-50s included spending time in the hands of the people who created the Qur’an, we can never know for sure.7

The Qur’anic story of Jesus’ non-crucifixion (4:157-58) is of more certain provenance: it comes from the Gospel of Basilides, a gnostic tract that the Church Fathers—Origen, Irenaeus, and Hippolytus—condemned back in the second century, nearly half-a-millennium before Muhammad’s revelations.

The fact that the Qur’an so often seems, as Tom Holland once put it, like “a Jurassic Park of [Jewish and Christian] theologies”,8 is at least explicable within the framework of a Muhammad-centric narrative of the Qur’an’s creation: whatever the method of acquisition of the texts, and whatever the reason they were revived from the amber, a scenario can be imagined where a Biblically-enthused Arab in the Levant who believes himself to be a Prophet brings these elements together in the early seventh century.

Where things get really perplexing is the carbon dating of the earliest Qur’ans.

The “Birmingham Qur’an”, two pieces of parchment found in Egypt in the 1920s, have been dated to 568-645 AD, thus potentially two years before Tradition says Muhammad was even born and forty years before he started receiving Qur’anic revelations in 610, and between a decade and nearly a century before Uthman’s recension in 653. At first sight, the dating appears to put paid to the Tradition around the Uthmanic codex, and bring into question Muhammad’s authorship of the Qur’an in any form, whether as the vehicle of angelic revelations or by more temporal means. But then, perhaps these dates apply to the parchment, not the ink. As so often in Qur’anic Studies, data is thrown up that seems to yield solid ground—and then gives way again on examination. It is difficult to know what to make of this, if anything.

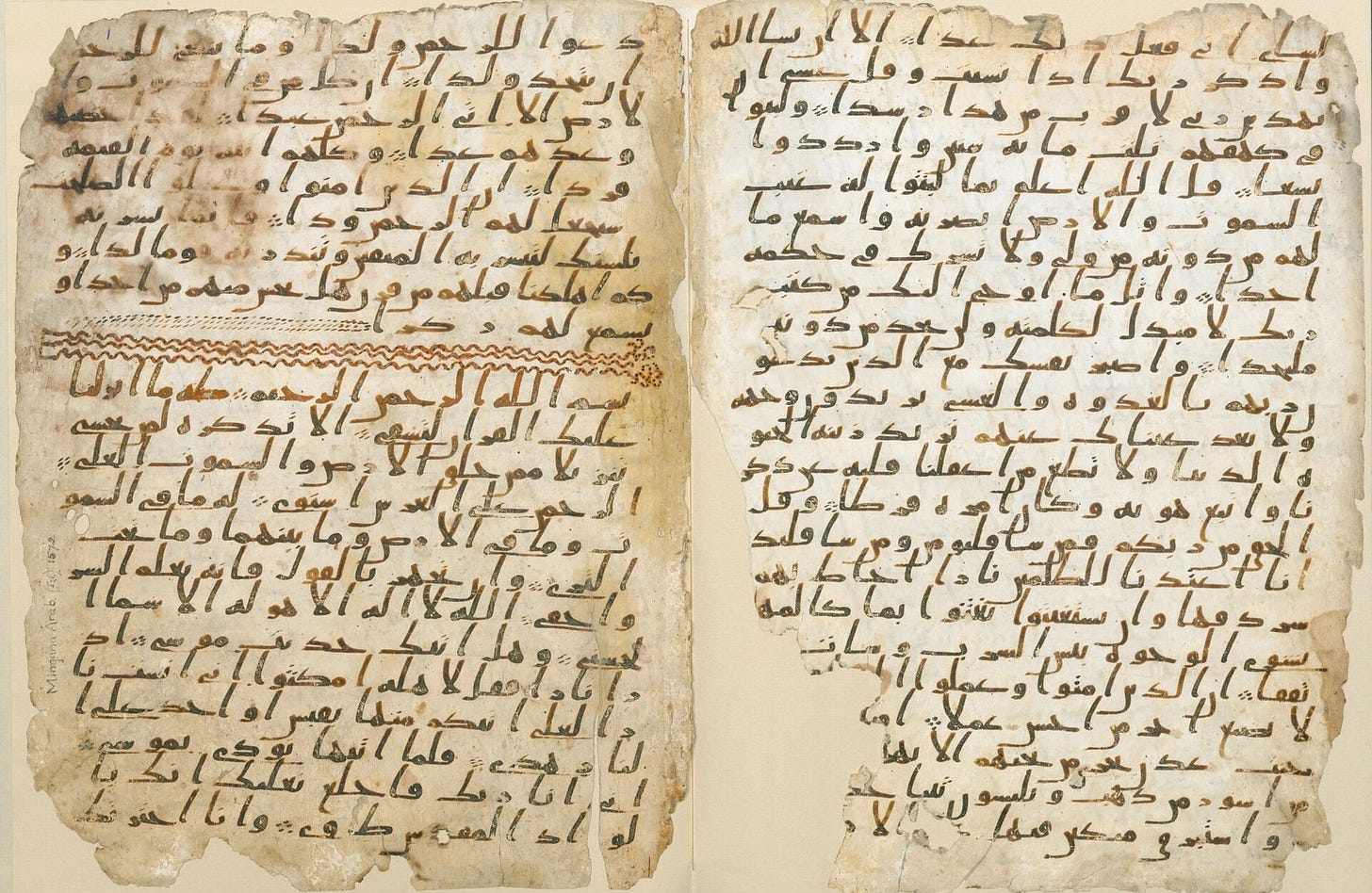

More difficult still is the so-called Sanaa Qur’an, discovered in the ceiling of the Great Mosque of Sanaa during renovations in 1972-73. The manuscript is a palimpsest—the “upper” layer of visible text has a “lower” layer of (original) text that has been written over. Three sets of Western scholars have studied the Sanaa palimpsest, but there have been interruptions in access and other hindrances from the Yemeni government, which was not best-pleased when Gerd Puin, one of the first to work on the documents, said publicly that they demonstrated the Qur’an “is a kind of cocktail of texts that were not all understood even at the time of Muhammad. Many of them may even be a hundred years older”, that is dating to the first decades of the sixth century.

In 2012, part of the lower Sanaa text was published and in 2015 Gabriel Said Reynolds was able to summarise the state of play. Fragments of the Sanaa manuscript have been dated to 543-643 and 433-599. As Reynolds notes, the latter dating, in particular, was so early that some Qur’an scholars considered it an obvious error. That could be, or not, but there seems little doubt this is the most ancient known Qur’an, and its contents raise a number of questions. The Sanaa Qur’an varies from the “canonical” Qur’an in its wording, and the “skeleton”, i.e. the structure of the suras, differs in ways not previously seen.

Given, as Reynolds notes, that “[b]oth the lower text of the Sanaa palimpsest and the text of the Birmingham manuscript include certain features—such as dividers between suras, and certain dashes to distinguish consonants—which may represent a later stage of writing”, it means yet older Qur’an manuscripts might be discovered.

On the one hand, this would seem to lay to rest Wansbrough’s late-codification theory. On the other hand, the implication is that the “Ur-Qur’an” was fully written down and codified long before the advent of the Ishmaelite Empire in the 630s-40s, albeit with some subsequent edits, which would necessitate a recalibration of the main lines of inquiry in Qur’anic Studies since, inter alia, it would radically expand the range of answers to the question of Muhammad’s relationship to the Qur’an, and it would pose challenges to the historiography that uses the Qur’an as source material about the Ishmaelite community in the pre-conquest phase.

Ultimately, the hyper-early-codification theory falls into the same no-man’s land as many other theories of the Qur’an’s origins: enough extant evidence against it to doubt it, not enough evidence to refute it, and enough evidence in its favour that it remains alive as a possibility.

NOTES

Fred Donner, ‘The Qur’an in Recent Scholarship: Challenges and Desiderata’, in, Gabriel Said Reynolds [ed.] (2007), The Qur’an in its Historical Context, p. 29.

Muhammad is mentioned by name just four times in the Qur’an: 3:144, 33:40, 47:2, and 48:29.

The early-codification camp is deeply divided within itself about the dates and methods of codification. For example, Angelika Neuwirth’s view of the Qur’an as a rhetorical performance that circulated only in oral form during the Prophet’s lifetime, necessarily meaning there was some fluidity to sura order and wordage for the later compilers to sort through, radically conflicts with John Burton’s contention that the Qur’an was collected and written during the Prophet’s lifetime, with the disputes emerging after his death and then being composed.

The most common version of the Tradition is that the Qur’an was largely in oral circulation when Muhammad died in June 632, with some hafiz who had memorised the whole thing, and the Prophet’s Companions (Sahaba) and others keeping parts of the Qur’an either in their minds or written on palm leaves, animal skins, and camel bones. After the Battle of Yamama in December 632, so many huffaz were killed that the first Caliph, Abu Bakr (r. 632-34), asked Zayd ibn Thabit, himself a hafiz and the personal scribe of the Prophet, to gather the fragments and write a whole manuscript so the Word of God would not be lost. The seven variants after this are cast by Tradition as essentially regional dialects, all equally valid, and Uthman (r. 644-56) as a light copy editor who harmonised the text twenty years later.

There is an immediate problem here because all these dates originate in biographies of the Prophet produced two centuries later. There is, for instance, evidence from outside the Tradition that Muhammad was still alive at least as late as 634, and how that is to be squared with the conventional dates for Abu Bakr’s reign is a question with as many answers as there are scholars. But even if we stick to the Tradition, the problems are legion.

For a start, the Tradition is clear that most of the caliphal troops at Yamama were recent converts, not learned believers. Then there are the flatly contradictory stories in Islamic historiography. According to one narrative, the gathering of the Qur’anic text on leaves and leather had begun during Muhammad’s life, and Abu Bakr merely sorted the assemblage. By another narrative, the gathering only took place during Uthman’s reign. See: Michael Cook (2000), The Koran; A Very Short Introduction, p. 121.

Andrew Rippin, who left us in 2016, took a view similar to Wansbrough’s. The most prominent living adherent of the Wansbrough school is probably Gerald Hawting.

Donner, ‘The Qur’an in Recent Scholarship’, The Qur’an in its Historical Context, p. 43.

Tom Holland (2012), In the Shadow of the Shadow of the Sword: The Battle for Global Empire and the End of the Ancient World, p. 318.

The quote is from a Rest is History podcast about Muhammad (46:10), 3 June 2021.

I was ready to believe Wansborough when I started studying the western academic discourse into the Qur'an. However, I came away convinced that he is wrong. The text is consistent with one composer, someone familiar with "street preaching" of Jews and Christians but not read into the bible, who is subtly altering their story over time, as their relationship to actual communities of Jews and Christians changes. Radiocarbon dating tells us the age of the paper or ink, not the age of the text. There's also the argument about the Hadith, but I won't bore you: the bottom line is they ought to be older too if the Qur'an was older.