Remembering Entebbe: When Israel Fought Back Against the Soviet “Anti-Zionist” War

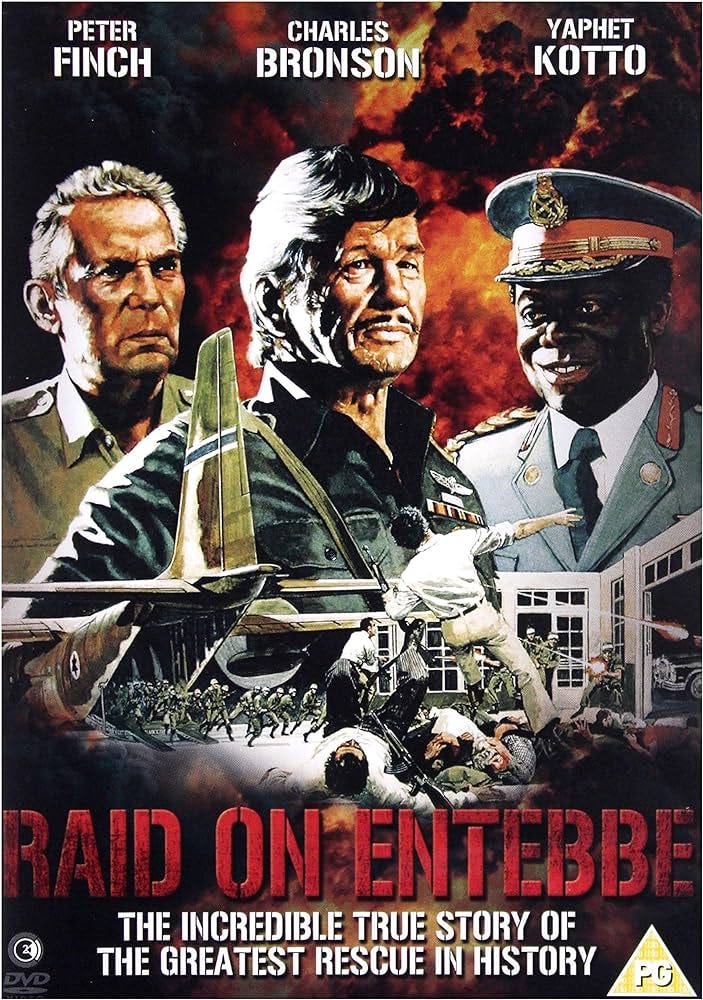

Film Review of ‘Raid on Entebbe’ (1977)

Raid on Entebbe (1977), a television movie for NBC, was released within six months of the July 1976 Israeli rescue mission for the hostages held in Uganda. The film covers the decision-making process and implementation of one of the most iconic military operations in history. Indeed, the film—one of three made in the 1970s about the raid—is part of what made Entebbe so iconic, and helped build the reputation for daring and efficacy that attaches to Israel’s military and intelligence services to this day.

THE HIJACKING

The film begins at the airport in Athens on Sunday, 27 June 1976, where Air France Flight 139, which has just departed from Israel, has called in to pick up passengers on its way to Paris. One advantage of the film being made so close in time is that it preserves the atmospherics of the 1970s: the garish decor, how people spoke, and how they looked, notably the long hair for men and the outrageous collars and moustaches.

Shortly after take-off from Greece, four terrorists carrying guns and grenades hijack the plane, announcing themselves as representing the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), specifically its “Che Guevara Group, Gaza Brigade”.

A disadvantage of the film being made so close in time is that it is rather unclear on who exactly the terrorists are, and this is not simply because information was covert at the time that has since become available, though this is a factor.

Other than the initial announcement that the PFLP has done this by one of the Palestinian hijackers, and a few references to two of the hijackers being German, the only other real context given is the other Palestinian on the plane explaining to passengers over the intercom:

You are in the hands of an international revolutionary movement. We have done this to punish the French who sold Mirage aircraft and a nuclear reactor to the fascist Israelis, and to avenge the murder of innocent Palestinians throughout the world by the bloodthirsty imperialist State of Israel.

WADI HADDAD

The name Wadi Haddad is never mentioned in the film, yet he was the mastermind, as Israel’s government knew from the first moments. Given that the film’s whole narrative lens alternates between the hostages and the Israeli Cabinet, this is no small failing.

The Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) had been formed in May 1964, under the guidance of Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Egypt, bringing together the various Palestinian factions under the leadership of Yasser Arafat and his FATAH group with the mission to eliminate Israel.1 After Israel defeated the second attempt at her annihilation in a generation in the Six-Day War of June 1967, George Habash, a Greek Orthodox Christian by birth and a Communist and Arab nationalist by ideology, formed the PFLP, a merger of several Marxist-Leninist factions. The PFLP, backed by the Ba’th Party regime in Syria, joined the PLO in 1968, becoming the PLO’s second-largest faction, and has remained there, despite various periods of tension as the PFLP has tried to outflank FATAH in its rejectionist “purity”.

The version of the story that the PFLP tells is that Haddad was to Habash within the PFLP what Habash was to Arafat within the PLO—an internal irritant, whose excessive radicalism in defiance of the leadership brought negative consequences. This narrative tends to point to the Dawson’s Field hijackings in September 1970 as the breaking point. After the PFLP landed four hijacked planes in Jordan, leading to an international crisis and then a PLO uprising in Jordan, the result would be remembered as “Black September”: the Jordanian monarchy pitilessly suppressed the rebellion and expelled the PLO to Lebanon—where they soon plunged that country into civil war, too. It is said that Haddad was thrown out of the PFLP at some point in the early 1970s—various dates are given—and went into business on his own, based in Iraq under the patronage of the Ba’th Party regime there, a rival of its Syrian sister that was not yet totally controlled by Saddam Husayn. In this telling, Haddad’s “Special Operations Group” (SOG) continuing to claim attacks in the name of the PFLP was deceptive.

The problem is: there is no evidence Haddad was ever expelled from the PFLP. The story seems to have been designed to give not only Habash, but more importantly the PLO “deniability”. Arafat had appeared before the United Nations with his “olive branch” in November 1974, beginning the process of his legitimisation in the international system. Brazen antisemitic atrocities were (and are) core to the PLO’s identity, but public association with same was unhelpful. Haddad was not the only instance of this kind of thing. Arafat had his own personal secret terrorism unit, Black September, infamous for the gruesome massacre of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics in September 1972.

Perhaps all of this was a bit complicated for a hastily put-together film, and the question of Haddad’s ultimate loyalty would surely have been botched on the then-available evidence, but, in a film about Haddad’s most audacious action, it is not really defensible that none of this was presented and he was not even mentioned, especially when the film runs over two hours.

THE SOVIET OMISSION

There is another layer to Haddad’s ultimate loyalty that certainly would not have made it into the film: Haddad was a KGB agent and had been since 1970, thus the PFLP’s terrorism, including the Entebbe hijacking, was functionally under Moscow Centre’s control. Nor was this an aberration. The architects of the Munich Massacre were the KGB’s men or as good as. It is a remarkable fact that the Soviets were behind probably the two most infamous terrorist episodes against Israel, Munich and Entebbe.

The film rather drops the ball in not dwelling on Munich. There is one passing reference, when someone in the Israeli Cabinet cautions that they “don’t want another Munich”. But really it is Munich that sets up the whole dilemma for the Israeli government over Entebbe that the film focuses on because while Israel had a general no-negotiations-with-terrorists policy, it had been raised to an ironclad State doctrine under Prime Minister Golda Meir (r. 1969-74) and upheld in the most difficult circumstances. Meir had refused to negotiate over Munich and unleashed Operation WRATH OF GOD—still ongoing at the time of Entebbe—to hunt down those responsible for the atrocity, setting a precedent the Israeli leadership could not easily break in 1976.

Similarly, while the writers could not have known the PFLP acted at the Soviets’ behest, they are not off-the-hook for leaving out this aspect, since the Palestinian terrorists’ Soviet orientation was undisguised, both at the level of the PLO, which was visibly close to Moscow, and the PFLP was a straight-out Moscow-line Communist outfit, as were their German collaborators, Wilfried Böse (played by Horst Buchholz) and Brigitte Kuhlmann, founding members Revolutionäre Zellen (“Revolutionary Cells” or RZ), one of the Soviet-underwritten “urban guerrilla” groups of the era.

The Soviets waged an undeclared war against Israel from shortly after the Jewish State’s refoundation, once it became clear the Israelis would not be an outpost of anti-Westernism and Stalin got lost in his antisemitic mania. Stalin died in 1953, but antisemitism—always referred to as “anti-Zionism”—remained central to the KGB’s understanding of the world for the remainder of its existence.

The war against “Zionism” had been a factor in the Soviet near-colonisation of Egypt in the 1950s and 1960s.2 With Nasser’s regime in disarray after the 1967 defeat, and the KGB—by then virtually running Soviet foreign policy—believing it could win the Cold War in the “Third World” , the Soviets took a more direct hand. The Soviets, having played a role in creating the PLO and continuing to broadly guide it,3 had largely dealt with the PLO at one step remove via Nasser. After Nasser’s death in 1970, the intermediary role would be played by the tightly Moscow-controlled Eastern Bloc KGB clones, as it usually was in Soviet dealings with its terrorist assets. The Soviets interfaced with the anti-Israel terrorists significantly via the Stasi, which had little difficulty modifying the expression of its antisemitism from Nazi-era biological racism into progressive “anti-Zionism”. The Soviets put the PLO to use, in combination with Moscow’s Syrian ally, creating a PLO-run ecosystem in the Syrian-occupied areas of Lebanon that exported terrorism against Jews and the West all around the world.

What makes the film’s neglect of the Soviet role less forgivable is that Moscow’s war against Israel was not all in the shadows. Alongside the kinetic war against Israel through terrorist cut-outs, the KGB ran more active measures against “Zionism” than any other target, save the Main Adversary (America), and by the mid-1970s this covert political warfare had a very public dimension. Less than a year before the Entebbe raid, in November 1975, the Soviets had directed the United Nations General Assembly to pass the “Zionism is racism” resolution, putting the Jewish national liberation movement in the same category as “colonialism”, “foreign occupation”, and “apartheid”.

It might have been thought unwise for the Soviets to bring up foreign occupation and colonisation while its Empire encompassed half of Europe and many other colonial outposts in Africa and Latin America, not to mention this being a half-decade after the crushing of Czechoslovakia, but such considerations never mattered at the United Nations, which did not regard its decolonisation mission as applicable to areas under Communist rule. Just to make doubly sure, the Soviets had suborned the U.N. Secretary General Kurt Waldheim, a Nazi war criminal whose history was still secret from all-but the KGB in 1975. (Whether Waldheim would have needed any prompting to assist in delegitimising Israel is open to doubt, but the Soviets took no chances.)

If the language of the Soviets and their PFLP terrorists—“fascist Israelis”, “bloodthirsty imperialist State of Israel”, “colonialism”, “apartheid”—sounds similar to the political warfare being waged against Israel in the U.N.’s court system at the present time, it should: this Soviet active measures campaign in the 1970s to portray Israel as racist and genocidal—the “real Nazis” of our time—is the origins of it, and the current vanguard of the effort at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) is an old Soviet terrorist group.

THE HOSTAGES ARRIVE IN IDI AMIN’S UGANDA

Underlining the strange lacuna around the Soviet “anti-Zionism” campaign, when the “Zionism is racism” resolution was being “debated”, one of the most virulent and unhinged speakers in its favour was Uganda’s tyrant, Idi Amin, whose racism had extended to a wholesale expulsion of Indians from Uganda a few years earlier. Amin (played by Yaphet Kotto) is a central figure in the film because it was to his country—Entebbe is a town in south-central Uganda—that the PFLP took Air France Flight 139, after a stopover in Libya, ruled by another close Soviet ally, Colonel Muammar al-Qaddafi, to refuel and pick up three more PFLP operatives. (Qaddafi’s Libya was one of the PFLP’s home bases. The other was South Yemen, the only fully Communist State in the Arab world.)

The hijacked plane landed at Entebbe on 28 June 1976 and the Ugandan army helped herd the 248 passengers and twelve crew into an abandoned airport terminal. As shown in the film, Amin visited the hostages virtually every day and kept using the word, “Shalom”, which was initially something of a comfort to the many Israeli and Jewish hostages, until it dawned on them that Amin was quite, quite mad.

Ms. Kuhlmann is shown telling the passengers that the PFLP’s demands are for a ransom payment and the release of 53 “revolutionary heroes” imprisoned in France, West Germany, Switzerland, and forty of them in Israel, with a deadline of Thursday, 1 July, or else the plane and all the hostages will be “eliminated”. The Cabinet meetings accurately portray Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin (Peter Finch), leader of the Left-wing Labour Party, being prepared to negotiate on the point through the French, while many members of his Cabinet protest at the principle of negotiating with terrorists and the particulars of releasing terrorist murderers.

The key moment of the Entebbe saga, showing the nature of the Palestinian terrorists (and Amin), came on 29 June when those hostages with Israeli passports and those who were visibly Jewish were separated from the others, moved into a separate room, created by the Ugandan troops knocking through a wall. One Israeli dual citizen escaped detection because he was travelling on a French passport, another dual citizen identified herself, and a couple of very brave non-Jews insisted on going with the Jews.

Raid on Entebbe does include a section where the hostages talk about the fact that these Communist camp guards are no different to the Nazis of thirty years earlier, but the film misses an opportunity by omitting a genuine incident. During the real-life segregation of Jews, one of the Israeli hostages pointedly showed the concentration camp number tattooed on his arm to Böse, who indignantly replied: “I’m no Nazi! I am an idealist.” So he was, and so were the Nazis, of course. Those young Germans moved by the “Baader-Meinhof complex”—the belief that West Germany’s democracy was a thin veneer over Nazi foundations (not in itself wholly untrue) and this justified their hysterical violence—never could see the irony that they were the nearest thing Germany in the 1970s had to an Einsatzgruppen.

As the Israeli military tries to put together a rescue plan, Rabin buys time—and keeps his options open—by continuing to negotiate through France. Rabin was also able to shore-up the home front, getting the support of Menachem Begin (David Opatoshu), the leader of the Right-wing Likud opposition, for a raid.

On 30 June, 48 women, children, and elderly non-Jewish hostages are released, and Amin basks in the glare of the international press as a “peace-maker”.

The Israeli government is shown—true to reality—as being initially slightly unsure of what Amin’s role is. This was partly because, as alluded to (Israel “broke with Uganda”), Israel had close relations with Amin for his first year in power (1971-72) within the framework of its “doctrine of the periphery”, at a time when Amin was ostentatiously pro-Western and particularly pro-British. The Israelis had helped train Amin’s security forces and MOSSAD had been given tacit free-run in Uganda. Amin’s turn to funding from Libya and “advisors” from the Soviet Union and the Captive Nations downgraded these links, and the expulsion of the Indians in the late summer of 1972 terminated them. The other part was that Israel had difficulty conceiving of a State using its national army to directly and publicly support international terrorism.

To try to get some clarity, as seen in the film, Israel got retired Israel Defence Force (IDF) officer Baruch Bar-Lev, an old personal friend of Amin’s, to speak on the telephone with Amin. It quickly became clear Amin was in fact a willing collaborator with the terrorists. Bar-Lev tried to dissuade Amin from this course, telling Amin he was the ruler, he had the power to free the hostages, and he could win acclaim for himself as a statesman, maybe even the Nobel Peace Prize, if he did so. Amin obviously did not go for that, but Amin was persuaded to extend the deadline from 1 July to noon on Sunday, 4 July, allowing him to attend an African Union summit—he was the chairman at the time and was handing over to Mauritius—where he could receive further adulation from the “anti-imperialist” servants of Soviet imperialism.

As well as confirming that Amin did have control over the situation, making the Ugandan military legitimate targets during the raid, the additional time Bar-Lev’s calls bought proved crucial for the Israeli military: they were able to solidify their plan by inter alia debriefing the hostages who had been released, gathering intelligence on the layout of the facility where the captives were held that was used to build a partial model of it, and getting an idea of how many guards there were and what they were armed with.

The additional time also allowed Israel to diplomatically secure the cooperation of Kenya, something shown in the movie. The Haddad element is again missing, though. Haddad—guided by his KGB handlers—was the “best strategist in the terrorist world”. In addition to the meticulous intelligence-gathering and other preparations that went into hijacking Air France Flight 139, Haddad had carefully selected the Soviet-friendly regimes that would provide the logistical assistance, Libya and Uganda, because they were so far out of Israel’s reach. The Soviets had been aware of the Western influence in Kenya—and saw Red China’s influence in Tanzania—which is why Moscow moved into Uganda as a counter-weight. But the Soviets had not banked on Kenya being prepared to risk retribution from Amin and the Palestinians by semi-publicly cooperating with Israel.4 The Kenyans might not have been prepared to shoulder the risk without the efforts of the British SIS/MI6 to convince Nairobi their interests would be served by helping Israel.5

The remaining 100 non-Jewish hostages were released on 1 July. The twelve-member crew, led by Captain Michel Bacos (Eddie Constantine), very decently and courageously refused to leave when offered the chance, staying behind with the 94 Jewish hostages.

THE ENTEBBE RAID

By this point, the balance of risk had shifted for Israel. The political and security cost of releasing terrorists was extreme, and the military had completed the plans for Operation THUNDERBOLT, as the Entebbe raid was officially known. If the PFLP had agreed to move the hostages-for-terrorists exchange point to a more neutral venue like Tunis, where Israel did not have the additional burden of risk in flying into an environment wholly controlled by her enemies, it might have complicated deliberations in the Israeli Cabinet. As it was, the PFLP’s intransigence sealed their fate.

At about 14:00 Israeli time on 3 July, the 100 or so Israeli operatives seconded for the THUNDERBOLT operation took off from Israel. The flight to Entebbe, more than 2,500 miles away, would take seven hours. Prime Minister Rabin had given the go-ahead on his own authority to make the mission possible, but he still had to get Cabinet approval; if there was not unanimity, he would have aborted the mission. The suspense over this decision forms an important part of the third quarter of the film, with some slight comic relief when Israeli Air Force (IAF) commander Major General Benny Peled (John Saxon) insists on being the one to relay this decision to the team, and Brig. Gen. Dan Shomron (Charles Bronson) announces it over the Tannoy on his plane, to an anticlimactic reception as most of the soldiers are asleep.

The Israeli operation in Entebbe relied on the element of surprise. The Israelis had set out on Shabbos (3 July was a Saturday), something the PFLP could not have expected. The Israeli troops would land at Entebbe in four C-130 Hercules transport planes, which would fly low to avoid Ugandan radar systems, under cover of darkness. A detachment of about thirty special forces operatives from the elite Sayeret Matkal, led by Lt. Col. Yonatan “Yoni” Netanyahu (Stephen Macht), were to disembark from the planes and drive up to the old terminal where the hostages were held in a motorcade led by a black Mercedes of the kind Amin used.6 Theoretically, within two or three minutes of the vehicles leaving the Hercules, Sayeret Matkal would commence storming the terminal, taking advantage of the confusion, and killing the terrorists and any Ugandan soldiers present. The paramount concern was eliminating the terrorists guarding the hostages, since it was understood that they would begin murdering the hostages as soon as they realised a rescue mission was underway. The other Israeli paratroopers and soldiers were to follow behind, securing the control tower, destroying Uganda’s Soviet-supplied air force on the ground, and creating a perimeter to hold off any Ugandan reinforcements that were mobilised to allow enough time to get the hostages onto the transport plane and away.

The mission had two additional aircraft, Boeing 707s, one of which was an airborne hospital that waited in Nairobi to link up with the main team when they stopped to refuel on the way home, and the other circled over Entebbe as a command and control station led by General Yekutiel Adam, the Deputy Chief of Staff of the IDF and the overall commander of THUNDERBOLT. Raid on Entebbe accurately shows the Boeings in their roles, but Adam is not a character in the film for some reason.

The Israeli planes landed in Entebbe at 23:01 on 3 July Israeli time (a minute after midnight on 4 July Uganda time), just thirty seconds behind schedule. The film also takes a slight liberty with how the mission unfolded. In reality, the element of surprise was nearly lost because the two Ugandan soldiers standing sentry immediately recognised the lead car was not Amin’s—the tyrant had recently swapped his black Mercedes for a white one, and this piece of intelligence had eluded the MOSSAD. The two Ugandans were shot dead with silenced weapons, but one of the Sayeret Matkal operatives in the two Land Rovers following the Mercedes thought they were still alive and fired on them with an unsuppressed weapon. The film leaves out the intelligence error over the white Mercedes and the unsuppressed fire, doubtless to make the story smoother, and since it did not affect things—the Israelis were able to enter the terminal without the terrorists having any warning—this is not unreasonable.

Sayeret Matkal burst into the old terminal, shouting in Hebrew and English, “Everybody down! We are Israeli soldiers!” The four terrorists in the room with the hostages, including the two Germans, were killed, though not without difficulty, as the film captures: because the terrorists were dressed in civilian clothing, they hid among the hostages and used them as human shields. Three hostages were killed in the cross-fire and about ten of them injured. What is not shown in the film is that the three “off-duty” terrorists in the adjacent hall tried something similar, acting calmly when approached by the Israelis, who were unsure if they were civilians until one of them threw a grenade. By the time the fourth Hercules landed—the empty one for the hostages—six minutes after the first, all the PFLP guards were dead and the Israelis had control of the hostages. Evacuating the hostages began soon afterwards and the Ugandan MiG fighter jets were destroyed to prevent them being used to follow the Israelis and kill the hostages in the air.

The Ugandan army did respond, as expected. Between the soldiers who tried to pierce the Israeli perimeter at the airfield and those present at the gates and in the watchtower, 40-odd Ugandans were killed. Five Israeli soldiers were wounded in the raid and it was a Ugandan soldier who inflicted the sole fatality on Israeli forces: Yoni Netanyahu was shot in the back during the final stages of the evacuation by a Ugandan soldier in the watchtower who had, unnoticed by the Israelis, survived the initial barrage. In Netanyahu’s honour, Operation THUNDERBOLT was retrospectively renamed Operation YONATAN (Mivtsa Yonatan).

58 minutes after landing at Entebbe, the Israelis had departed, landing in Israel to a euphoric celebration.

AFTERMATH

Raid on Entebbe was never going to win any Oscars, but it is entertaining as an action flick—it does not feel like a 135-minute movie—and it is reasonably historically accurate, with the obvious exception of the Soviet lacuna, which cannot be judged too harshly given that most journalistic and scholarly accounts of the Entebbe raid downplay the Soviet superintendence.

In the final tally, 102 out of 106 hostages were rescued. Of the four who did not make it out, three were killed in the crossfire, as mentioned, and the other was Dora Bloch, who had quite a prominent role in the film, played by Sylvia Sidney. A Jewish woman born Dora Feinberg in Jaffa in 1901, in what was then-the Ottoman Empire, Feinberg became Mrs. Bloch in 1925 after marrying a Jewish soldier in the British Army during the Mandate era and thereby gained British citizenship, which she retained after the recreation of Israel. In July 1976, Bloch, a 75-year-old widow, was travelling to New York for her son’s wedding. As Bloch spoke Hebrew, English, Arabic, and German (as well as Russian and Italian), she served an important role during the crisis as a translator. At some point, Bloch was transferred to Mulago Hospital in Kampala after she choked on some food, and she received treatment for leg ulcers while there. The closing credits of the film note that the British Consul had visited Mrs. Bloch in hospital, but when he visited the day after the raid she had disappeared, never to be seen again.

Despite Amin’s claim that Bloch had been returned to the old terminal before the raid, there was never much doubt about the outline of what had happened to Bloch. Amin was humiliated and looked for defenceless targets to revenge himself. A British cable at the time said: “They may have seized on the only available Jew on whom to extract their revenge.” After persistent lies from the Amin regime, on 28 July 1976 Britain severed diplomatic relations with Amin’s Uganda, a first with a Commonwealth State, and only restored them after he was gone.

Several hundred Kenyans were massacred in the week or so after the raid as part of Amin’s revenge, and thousands more fled Uganda. Amin considered militarily attacking Kenya, but the damage Israel had done to his fighter jets prevented him doing so. In May 1978, Amin’s intelligence services were almost certainly behind the bomb on the plane that killed Bruce MacKenzie, the Scottish-born Kenyan Agriculture Minister, who was feted in Israel. (MacKenzie, close to Britain’s SIS and MOSSAD, had been a key figure in convincing Nairobi to cooperate with Operation THUNDERBOLT.) In the end, Amin did start a war with one of his neighbours, Tanzania, in October 1978, and not even the Soviet “advisers” and their deputised legions—troops sent by Col. Qaddafi and the PLO—could save him. In April 1979, Amin fled his capital to Saudi Arabia, where he remained an embarrassing guest until he died in August 2003.

With Amin’s downfall, the full story about Dora Bloch could be discovered: she had been dragged from her hospital bed in the hours after the raid by two soldiers acting on Amin’s orders and shot dead. Mrs. Bloch’s face was then badly burned to try to obscure her identity—her leg ulcers were part of what made identifying her possible in the end—and her body was dumped in the boot of a car with Ugandan intelligence plates, which was left near a sugar plantation twenty miles from Kampala. Bloch’s body was recovered and transferred to Israel for burial in late 1979.

If dealing with Amin, the second-most responsible man for the Entebbe situation, was something that had to be left to an act of God—or the Tanzanian army, anyway—Israel was able to take into its own hands the settling of accounts with the prime mover, Wadi Haddad. Arafat’s international charm offensive gave him a stature that, in the judgment of Israeli intelligence, made it too politically costly to kill him. Haddad moved to the top of the list and in early January 1978 the MOSSAD agent in Haddad’s inner circle, known only by the codename SADNESS, “switched Haddad’s toothpaste for an identical tube containing a lethal toxin”. Over the next few weeks, the toxin built up in Haddad’s system, and by March 1978 Haddad was seriously ill. The doctors in Saddam’s Baghdad suspected poison, but had no idea what it was. Showing the falsity of the claim that Haddad had been “expelled” from the PFLP/PLO,7 Haddad called on Arafat and Arafat contacted his Stasi friends to have Haddad transferred to one of the hospitals that catered to the Communist elite, and thus actually worked, in East Germany. Haddad’s aides packed some belongings for him, “including a tube of the deadly toothpaste.” After ten days of bafflement for the medical staff of the “German Democratic Republic”, on 29 March 1978 Haddad died, reportedly having spent the whole time in excruciating pain, alleviated only by sedatives.

On the Israeli side, this phase of Rabin’s political career was drawing to a close. Some of the problems related to Rabin’s government specifically, notably a series of corruption scandals. But in many ways Rabin drew the short straw: he was made to pay for the accumulated failings of thirty years of Labour hegemony. Israel had gone the furthest towards socialism of any country outside the Soviet Empire and really as far as it was possible to go under a constitutional system. (Only Britain at the time could be compared with Israel’s socialist experiment.) Menachem Begin’s Likud made populist hay out of the economic stagnation and politicised inequalities this form of egalitarianism creates. Another aspect of this was Begin’s appeal to the Mizrahim, the Jews from Arab countries subject to various forms of discrimination by the Ashkenazi elite.8 The failings of the 1973 Yom Kippur War were also still fresh in mind. The success of Entebbe could not outweigh these issues. In March 1977, Labour was defeated for the first time in an election. Begin became Prime Minister and set a course for a more open economy (the same path Britain would follow under Margaret Thatcher two years later), though did not radically change foreign policy and much to the surprise of many in the security establishment soon signed Israel’s first peace agreement with an Arab State, Egypt, handing back the Sinai that had been captured in the defensive war of 1967.

Rabin returned to the premiership in 1992 and led the peace camp as Israel embarked on the Oslo process, (in)famously shaking hands with Arafat on the White House lawn in September 1993. Rabin succeeded in signing Israel’s second Arab peace accord, with Jordan, more a formalisation of reality than a breakthrough, but there it was, and then Rabin was assassinated by a Jewish zealot in November 1995. The Israeli Left and many outside Israel regard this as the moment the two-State “solution” was doomed, but this misunderstands the conflict—putting the onus on Israel—in a way Rabin himself never did. At the time of his death it was already clear Arafat had not changed; the escalating campaign of suicide bombings was a testament to that. A half-decade later, Arafat and his suicide bombers would kill Oslo, as well as 1,000 Israelis and the Israeli Left.

The major beneficiary of these changes has been Benjamin Netanyahu, who perhaps would not be where he is now if his brother had not perished at Entebbe. If Netanyahu’s success can in a sense be traced back to Entebbe, so can his impending political demise. The Israeli reputation for military-intelligence competence, which is not some ephemeral public-relations gimmick but a deadly serious aspect of the Jewish State’s security, was greatly enhanced by the Entebbe raid and has been grievously wounded by the 7 October pogrom, which Netanyahu is blamed for failing to prevent. Netanyahu’s plan to keep HAMAS quiet by facilitating the transfer of suitcases full of Qatari cash and his distraction with self-indulgent ideological projects like trying to reform the Israeli judiciary, done in such a way as to inflame societal polarisation and chaos, not to mention keeping himself in power by bringing incompetent lunatics into the government, have, to say the least, tarnished his image as “Mr. Security”. Most Israelis—including many on the Right—are waiting for the first opportunity to eject Netanyahu from office.

For those outside Israel, the resonance the Entebbe raid retains is partly because the drama of an underdog (tiny Israel) going into the lion’s den with no margin for error is simply a great story, told in numerous films and books, and military heroism is always a best-seller, no matter how much we are supposed to have progressed beyond admiring such things. There is, though, a distinctly non-“timeless” element that perhaps subconsciously has given Entebbe a special durability. Operation THUNDERBOLT took place at a moment in the mid-1970s when the West was at its lowest ebb: demoralised and devoid of self-confidence; racked with internal dysfunction as the social democratic consensus broke down, hastened by the “oil shock”; humiliated in Vietnam; and engaged in the ludicrous farce of détente, which in practice meant the West ceased resisting the global onslaught of Soviet Communism, notably by repeatedly giving in to its terrorists. Israel’s actions at Entebbe were, so to say, a bolt in this darkness; an act of stark moral clarity that recalled the West to its own values and traditions, a reminder that even small States should—and could, if they had the will—fight and destroy those we once called hostis humani generis, the enemies of all mankind, rather than bargaining with them.

NOTES

An interesting detail: the PLO’s founding “National Charter” phrased its determination to destroy Israel by claiming that “Palestine with the boundaries it had during the British Mandate is an indivisible territorial unit”, and all of it belongs to the Arabs. It might seem odd that the PLO should insist on an “imperialist” definition as the foundation of its cause, but it had no choice. After the destruction of Israel by the Romans in 135 AD, in the wake of the Bar Kokhba revolt, the zone was renamed “Palestina” or “Syria Palestina” to try to obliterate its Jewish identity. The territory of the former Judean principality—with regularly shifting administrative boundaries—became a subdivision in larger entities, a pattern that continued after the coming of Islam: “it was only with the British Mandate that, apart from the brief and obviously unsuitable interval of the Crusades, Palestine reappeared on the stage of history as a separate political entity”.

The Soviets played a key role in initiating the 1967 Egyptian-led Arab war against Israel by feeding Nasser false intelligence about Israeli preparations to attack Syria, a State with an Egyptian security guarantee.

The PLO’s “National Covenant” was drafted in Moscow under Soviet guidance by Ahmad Shuqayri, whose relationship with the KGB was close, even if he was not an official agent. Shuqayri was the first Chairman of the PLO, and resigned in the aftermath of the Six-Day War, briefly being replaced by Yahya Hammuda, before Arafat formally took over in February 1969.

The Kenyan government of Jomo Kenyatta (r. 1964-78) had covertly cooperated with Israel shortly before Entebbe. Haddad—with extensive assistance from the KGB, including the supply of Strela surface-to-air missiles—had planned to shoot down an Israeli plane, El Al Flight LY512, as it landed in Nairobi on 25 January 1976 with 150 mostly Jewish passengers on board. Haddad had picked two German Red Army Faction (RAF or Baader-Meinhof Gang) operatives, Thomas Reuter and Brigitte Schulz, training at the PFLP camps in South Yemen to act as spotters at the Nairobi airport, relaying to three Palestinians outside when the plane was coming in to land. Unfortunately for the PFLP, the MOSSAD had an agent in the PFLP near Haddad, codenamed SADNESS, and the Israelis worked with Kenya to secretly apprehend the “Nairobi five” before they could carry out their massacre. Kenya refused to keep the prisoners and Israel rejected the other option put to them by Kenyatta’s government: “take them to the desert and feed them to the hyenas for lunch”. The five PFLP operatives were, instead, transferred to a secret prison in southern Tel Aviv.

This was to be a factor in decision-making around Entebbe: the “Nairobi five” were among the 53 prisoners Haddad demanded be released—he could not be sure where they had “disappeared” to, but he (correctly) guessed Israel had something to do with it—and this created a serious dilemma, because those prisoners would be able to cause serious political damage to Israel, by disclosing an operation most of the world would see as illegitimate and Kenya’s assistance, which had been granted on the strict condition it remain covert, thus causing a crisis in Israeli-Kenyan relations.

Israel ultimately admitted to holding Reuter and Schulz in March 1977, after protests from the West German government, and the duo were sentenced to ten years in prison after pleading guilty at a non-public trial in September 1979. Israel released them in December 1980.

In fairness to the Soviets, it would have been difficult to predict a British helping hand to Israel. British-Israeli relations were—despite episodic cooperation, as over Suez or Entebbe—rather testy in many ways until after the turn of the millennium. A lot of this related to the circumstances of Israel’s rebirth in the late 1940s. On the one side, there was the shameful British evasion of Imperial responsibility in scuttling from the Mandate, after having essentially tried to revoke the Balfour Declaration, and then proving somewhat worse than neutralist in the war Israel had to fight in the shadow of the Holocaust against five invading Arab armies. On the other side, the Zionist terrorist campaign—particularly the King David Hotel bombing in July 1946—had left bitter memories in London, made all the worse when former Irgun commanders started attaining the Israeli premiership in the late 1970s. On top of that, the perennially “realist” orientation of the British Foreign Office made Israel seem an irritant, when set against hundreds of millions of Arabs with oil. This was the background to the British arms embargo on Israel after the 1982 invasion of Lebanon, which was not lifted until after the onset of the Oslo peace process in 1994. The power of the “Arabists” in the British establishment—and the “dual loyalties” trope of antisemitism—meant there was a virtual ban on Jews in senior security positions until Malcolm Rifkind became Foreign Secretary in the 1990s.

The question was raised at Cabinet by the commanders of THUNDERBOLT what they were to do if they encountered Amin himself during the raid. Rabin responded: “If he interferes, the orders are to kill him”. Foreign Minister Yigal Allon added, “Even if he doesn’t interfere.”

Major General Amos Gilad, a long-time prominent military-intelligence figure in Israel, put it this way to Ronen Bergman for his 2018 book, Rise and Kill First: The Secret History of Israel’s Targeted Assassinations (pp. 270-271): “He [Arafat] had two deputies for running terror operations, Abu Jihad [Khalil al-Wazir] and Abu Iyad [Salah Khalaf]”—both of them very close to the KGB, let it be noted—“but, except in one attack, you won’t find any direct connection to Arafat. … Abu Jihad got directives in principle, and he did the rest on his own. Arafat didn’t want reports, didn’t take part in planning meetings, didn’t okay operations.” Khalaf ran “Black September” for Arafat, the PLO unit behind the Munich atrocity, among other things.

While “Ashkenazi” and “Mizrahi” are the usual descriptors for this faultline in Israel, as Bernard Lewis pointed out a more accurate description would be the Jews of Christendom and the Jews of Islamdom.

I continuously appreciate how you're actually willing to look into all the sides of any conflict. To degrees I didn't know were possible. It gives me a lot to learn from in my own research. I didn't know people like you under the age of forty still existed in the Anglosphere, Kyle. It seems as though we do everything possible to ensure against such folk's existence.