The Most Infamous Russian Revolutionary Manifesto of the Nineteenth Century

“The Revolutionary Catechism”, by Sergey Nechayev

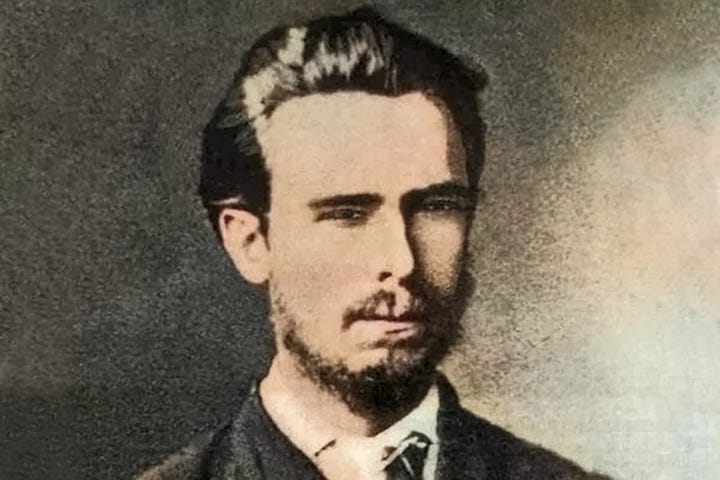

Below is a translation of the 1869 manifesto, “The Revolutionary Catechism”,1 by Sergey Nechayev, a Russian Jacobin and the most notorious representative of the Nihilist current within the Russian terrorist-revolutionary movement. The manifesto had some input—the extent of which is debated—from Mikhail Bakunin, the leader of the Russian Anarchists.

The Revolutionary Catechism

The Attitude of the Revolutionary Toward Himself

§1. The revolutionary is a doomed man. He has no personal interests, no business affairs, no feelings, no attachments, no property, not even a name. Everything in him is absorbed by one single, exceptional interest, one single thought, one single passion: the revolution.2

§2. He [i.e., the revolutionary], in the depths of his being, not only in words but in deed, has broken every tie with the civil order and with the whole cultured world, and with all of its laws, proprieties, commonly accepted conventions, and the morality of this world. He is a merciless enemy of all of this, and if he continues to live within it, it is only in order to destroy it the more surely.3

§3. The revolutionary despises all dogmatism and has renounced peaceful Science, leaving it for future generations. He knows only one Science: the Science of destruction. For this, and only for this, he now studies mechanics, physics, chemistry, and if need be medicine. For this he studies day and night the living Science of people, characters, circumstances, and all the conditions of the present social structure, in all possible strata. The aim is one—the most rapid and most certain destruction of this filthy order.4

§4. He despises public opinion. He despises and hates, in all its impulses and manifestations, the present public morality. Morality for him is everything that contributes to the triumph of the revolution. Immoral and criminal is everything that hinders it.

§5. The revolutionary is a doomed man, merciless toward the State and, in general, toward the whole of estate-educated society, and he must expect no mercy from them for himself. Between them and him there exists, whether in secret or in the open, a continuous and irreconcilable war to the death. Every day he must be ready for death. He must train himself to endure torture.

The Attitude of the Revolutionary Toward His Comrades in the Revolution

§6. Harsh toward himself, he must be harsh toward others as well. All the tender, enervating feelings of kinship, friendship, love, gratitude, and even honour must be crushed in him by the single cold passion of the revolutionary cause. For him there exists only one pleasure, one consolation, one reward, and one satisfaction—the success of the revolution. Day and night he must have one thought, one goal—merciless destruction. Striving cold-bloodedly and tirelessly toward this goal, he must always be ready both to destroy himself and to destroy with his own hands everything in the way of its attainment.5

§7. The nature of the true revolutionary excludes all romanticism, sentimentality, emotional enthusiasm, and infatuation. It excludes even personal hatred and vengeance. Revolutionary passion, having become in him a constant condition at every moment of the day, must be joined with cold calculation. Always and everywhere he must obey not that to which his personal inclinations urge him, but that which the cause of the revolution prescribes to him.

§8. The only friend or beloved for the revolutionary is someone who has shown themselves in deed to be dedicated to the same revolutionary work as he is. The measure of friendship, devotion, and other obligations toward such a comrade is determined solely by the degree of his practical usefulness in the cause of all-destructive revolution.

§9. As for solidarity among revolutionaries, there is nothing even to say. In this fact lies the whole strength of the revolutionary cause. Comrades-revolutionaries standing on an equal level of revolutionary understanding and passion, must, insofar as possible, discuss all major matters together and decide them unanimously. In carrying out a plan thus decided, each must, insofar as possible, rely upon himself. In the execution of destructive acts, each must act alone, and resort to the advice and help of comrades only when this is necessary for success.

§10. Each comrade must have at hand several revolutionaries of the second and third ranks, that is, not completely initiated. He must look upon them as part of the common revolutionary capital placed at his disposal. He must spend his share of the capital economically, always striving to extract from it the greatest possible benefit. He must also look upon himself as capital destined to be expended for the triumph of the revolutionary cause, however he cannot dispose of such capital alone, without the consent of the whole comradeship of the fully initiated.

§11. When a comrade gets into trouble, in deciding the question of whether to save him or not, the revolutionary must be guided not by any personal feelings, but only by [considerations of] the usefulness to the revolutionary cause. Therefore, he must weigh, on the one hand, the usefulness brought by the comrade, and, on the other, the expenditure of revolutionary forces needed for his deliverance; and the decision must be made according to which side carries more weight.6

The Attitude of the Revolutionary Toward Society

§12. A new member, who has proven himself not in word but in deed, can only be accepted by a unanimous decision of the comrades.

§13. The revolutionary enters the world of the State, the estate-bound classes, and so-called civilisation, and lives there only with the aim of its complete and rapid destruction. He is not a revolutionary if he feels compassion for anything in this world. There should be no hesitation before destroying a status, relationship, or any person belonging to this world. He must hate everything and everyone equally. So much the worse for him if he has in this world any family, friends, or love relationships; he is not a revolutionary if they can stay his hand.7

§14. For the purpose of merciless destruction, the revolutionary may, and often must, live within society, pretending to be not at all what he is. Revolutionaries must penetrate everywhere, into all the higher- and middle-classes, into the merchant’s shop, into the church, into the house of the barin [nobleman, lord, master], into the bureaucracy, the military, the literary world, the Third Section [secret police], and even into the Winter Palace [of the Tsar].

§15. This filthy social order must be divided up into several categories. The first category is those immediately condemned to death. The comrades should compile a list that ranks those so condemned by their relative harmfulness to the success of the revolutionary cause, and eliminate those at the top of the list before those lower down.

§16. In drawing up such a list, and establishing the above-mentioned order [for assassinations], one must not be guided by an individual’s personal villainy, nor even by the hatred he arouses in the comradeship or among the people. This villainy and this hatred may even be useful in part, helping to arouse a popular revolt. One must be guided by the measure of benefit that will result to the revolutionary cause from his death. Thus, those who are especially dangerous to the revolutionary organisation must be destroyed first, along with those whose sudden and violent death will strike the greatest fear into the government, depriving it of intelligent and energetic actors, and undermining its strength.8

§17. The second category consists of people whose lives are spared only temporarily, so that they may continue with atrocious acts that drive the people into the inevitable revolt.9

§18. To the third category belongs the multitude of high-placed beasts, people not distinguished by any special intelligence or energy, but who, by virtue of their status, enjoy wealth, connections, influence, and power. They must be exploited in every possible manner; ensnared, confused, and, as far as possible, made into our slaves by seizing their filthy secrets [to use for blackmail]. Their power, influence, connections, wealth, and strength will thus become an inexhaustible treasury and a powerful [source of] assistance for various revolutionary undertakings.10

§19. The fourth category consists of ambitious men of the State and liberals of various shades. With them one may [initially] conspire according to their [ideological] programs, giving the appearance that one blindly follows them, while working to bring them under one’s power, mastering all their secrets and compromising them to the utmost, making it impossible for them to turn back [even after they realise they have been deceived], and then using them to foment turmoil in the State.

§20. The fifth category is the doctrinaires, conspirators, and revolutionaries who prattle idly in [talking] circles or on paper. They must be unceasingly pushed and pulled forward, into practical, reckless declarations, which will result in the majority being destroyed without a trace and a few being forged into genuine revolutionaries.

§21. The sixth category, women, is important. They should be divided into three main types. Some—the empty-headed, irrational, and soulless—may be used as the third and fourth categories of men are. Others—the ardent, devoted, and capable, but not ours, because they have not yet worked themselves out to the true non-sloganeering and factual revolutionary understanding—should be used as men of the fifth category. Finally, women who are completely ours, that is, fully initiated and having wholly accepted our program, they are our comrades. We must look upon them as our most precious treasure, without whose help we cannot manage.

The Attitude of the Comradeship Toward the People11

§22. The comradeship has no other aim except the complete liberation and happiness of the people, that is, of the manual-labouring folk. But, being convinced that this liberation and the attainment of this happiness is possible only by the means of an all-destructive popular revolution, the comradeship will use all its forces and means to contribute to the intensification and spread of the people’s miseries and evils until their patience is exhausted and they are impelled to a mass revolt.

§23. By popular revolution, the comradeship means not a regulated movement according to the classical Western model—a movement which, always stopping with respect before property [rights] and the traditions of the social orders of so-called civilisation and morality, has up to the present been everywhere limited to the overthrow of one political form to replace it with another, and has sought to create a so-called Revolutionary State. The only salvation for the people is a revolution that destroys every kind of statehood down to its roots, exterminating all State traditions, orders, and classes in Russia.

§24. The comradeship, therefore, does not intend to impose upon the people any kind of organisation from above. The future organisation will without doubt be worked out from the popular movement and life. But that is the task of future generations. Our task is fervent, total, universal, and merciless destruction.12

§25. Therefore, in drawing close to the people, we must before all else unite with those elements of popular life which, since the foundation of Muscovite State power, have never ceased to protest, not in word but in deed, against everything that directly or indirectly connected with the State: against the nobility, against the bureaucracy, against the priests, against the guild world, and against the kulak parasites. Let us unite with this daring brigand world, the sole genuine revolutionaries in Russia.13

§26. To weld this world [of brigands] into one unconquerable, all-destructive force—this is [the purpose of] our entire organisation, conspiracy, and task.14

NOTES

Can also be translated as “Catechism of a Revolutionary”, from “Katekhizis revolutsionera” (Катехизис революционера).

The phrase “doomed man” comes from “chelovek obrechennyi” (человек обреченный), which can also be translated as “condemned” or “sentenced” man. The sense is of fatalism, a man already fated for destruction and given over to death.

The phrase translated as “cultured world” is “obrazovannym mirom” (образованным миром), the first word potentially translatable as “civilised”, “refined”, or “educated”, and the second as “milieu” or “sphere”. The reference is to the literate strata of Russian society.

The word translated as “dogmatism” is “doktrinerstvo” (доктринерство), which can be rendered “doctrinairism”. The idea is Nechayev despising the devotion to abstract and pedantic theory; his call is to action, by any means that are effective.

The phrase translated as “peaceful Science”, from “mirnaya nauka” (мирная наука), could also be given as the “Science of peace” or “peaceful scholarship”.

It was a core Narodnik concept, handed down from Nikolay Chernyshevsky, that art and literature, Science and scholarship, have no intrinsic value; to study them for their own sake is to waste time and resources that should be devoted to bringing about the revolution. The revolutionaries saw books and other cultural products merely as vehicles toward revolution; they were only useful if they were didactic propaganda. On this as so much else, Nechayev was a wholly faithful son of Narodism, a product of the mainstream Russian revolutionary tradition, whose only crime, as Fyodor Dostoyevsky pointed out at the time, was to put before the intelligentsia in plain words what they all yearned for.

“Harsh” is translated from “surovyi” (суровый), which could also be given as “severe”, “strict”, or “austere”.

The word given as “feelings” could also be translated as “emotion” or “sentiment”: it comes from “chuvstvami” (чувствами). “Usefulness” comes from “polza” (польза), and “benefit” or “advantage” would work.

The word translated as “compassion” is “zhal” (жаль), which could also be translated as “pity”, “sorrow”, or “regret”.

The word translated as “villainy” is “zlodeistvo” (злодейство), which could also be rendered “wickedness” or “wrongdoing”.

The word translated as “revolt” is “bunt” (бунт), thus “rebellion”, “insurrection”, or “uprising” would work. It could also be given in certain contexts as “riot”, since the connotation is of a spontaneous, chaotic, and violent upheaval.

“Beasts” could also be translated as “brutes”: it comes from “skotov” (скотов), literally “cattle” or “livestock”. The word translated as “status”, “polozheniye” (положение), could also be given as “position”.

The word translated as “comradeship” is “tovarishchestvo” (товарищество), which could also be rendered “fellowship” or “association”. The connotation is of a “collective”—another possible translation—that is bound together in a common purpose. “Group” is possible as a shorthand translation, but it is a bit inexact, conveying both more (in terms of organisational structure) and less (in terms of ideological devotion) than “tovarishchestvo” intends. “Society” is also possible in the sense of a secret society, but it has the same drawback as “group” in conveying an institutional formality “tovarishchestvo” does not. There is the additional problem in the context of Nechayev’s writing that it risks confusion over his Society and the society (общество, obshchestvo) he wishes to destroy.

“The people”—the idolised object in whose name the terrorist-revolutionaries operated—comes from “narod” (народ), which is roughly equivalent in Russian to “volk” in German. “Narod” had less of a racial connotation, though such associations were not absent, but it served the same political function as the touchstone of identity and moral authority for a collective that saw itself as victimised, with the corollary legitimisation of extreme violence against categories of people defined as enemies, whether internal polluters or external oppressors. It should be emphasised here that the collective using “narod” in this way was the Russian intelligentsia and the terrorists it produced: “the people” of the Russian revolutionary imagination bore little resemblance to the mass of people as they were in Russia, and the actual people never had much connection with the revolutionaries.

The word translated as “fervent” is “strastnoye” (страстное), which can also be translated as “zealous”, “ardent”, or “passionate”.

The phrase translated as “daring brigand world” is “likhoi razboinichii mir” (лихой разбойничий мир). “World” in this context is in the sense of “milieu” or “community”, or more loosely “(societal) layer”. “Daring” could be given as “bold” or “adventurous”; “dangerous” is fine; and “violent” or “wicked” could work depending on the situation.

The word translated as “brigand” is more exactly “robber” (in the highwayman sense), but it is derived from the word for “brigand” or “bandit” (разбойник) and in the context of this manifesto—with this section clearly influenced by Bakunin, who had rested his hopes of revolution on outlaws for twenty-plus years—“brigand” seems most appropriate.

The word translated as “unconquerable” is nepobedimyi (непобедимый), which could also be translated as “invincible”.