The Communist Massacre of the Russian Royal Family

In June 1918, about half-a-year after the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia, the regime began to murder the members of the deposed Royal Family, the Romanovs, as well as those people from the old Court who remained loyal. By January 1919, eighteen Romanovs and at least eleven non-Romanovs from among the Imperial entourage had been murdered.

THE FIRST ASSASSINATION

Shortly after midnight on 13 June 1918, the younger brother of Tsar Nicholas II (r. 1894-1917), Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich, 39, became the first Romanov victim of the Bolsheviks, murdered with his secretary, Nicholas Johnson, a British citizen.

The Tsar had tried to give Mikhail the crown after he abdicated in March 1917, but Mikhail refused and thereafter displayed a total lack of interest in politics, not unlike the Tsar himself who made no effort to reclaim his throne. The Bolshevik leader, Vladimir Lenin, had ordered Mikhail sent into internal exile in Perm in March 1918, where he was placed under a relatively lenient, if heavily surveilled, form of house arrest in the Korolev Hotel.1

In the last half-hour or so of 12 June, five armed men arrived in Mikhail’s room and ordered him to come with them. Mikhail refused and asked for credentials, insisting on seeing the head of the local Cheka (secret police). Little did Mikhail know that it was exactly this man, Gavril Miasnikov, who had been ordered by Lenin to kill the Grand Duke. Miasnikov, a long-time professional terrorist-revolutionary and also the chairman of the Motovilikha Soviet, had put together the hit team that now stood before Mikhail. There were threats to force Mikhail into compliance, but Mikhail eventually went peacefully after one of the men whispered something to him or to Johnson. While it is not known for certain what was said, it seems Mikhail—and Johnson, who insisted on going with him—were under the impression they were being rescued by monarchists.2

Mikhail and Johnson were driven out of town into a forest and shot to death. Exactly who fired the fatal shots and how is disputed. The two men were probably shot in the back after being told to get out of the car; this was the standard Chekist practice. The bodies were burned in a nearby smelting furnace.3

Having taken Mikhail and Johnson under a false flag, the Bolshevik deceptions now continued: rumours were spread that Mikhail had escaped and/or been “abducted” by “White Guardists”. Lenin took the unusual step on 18 June of giving a personal interview to the liberal paper Nashe Slovo, which was as critical of the Bolsheviks as anyone dared be and shunned by the regime for this reason, saying he could not confirm reports of Mikhail’s escape—and was also unsure if the fallen Tsar was alive or dead, a distinctly strange thing to say unprompted. The likelihood is that this elaborate disinformation campaign, like the murder of Mikhail itself, was a testing of the waters of domestic and international opinion for what was to come.4 The Bolsheviks had decided to make an end of the Emperor and his family.

THE MURDER OF THE TSAR AND HIS FAMILY

The anti-Bolshevik Volunteer Army (“the Whites”5) in the south had survived the Ice March in the Kuban and was now joined by the Cossacks, who had had a taste of Red Terror. In the east, the Czech Legion had erupted in mutiny and in short order cleared the Bolsheviks from most of Siberia, leaving space for the nucleus of an anti-Bolshevik government to take hold. There was a sense of threat to the Bolsheviks in the summer of 1918, of that there can be no doubt, and for good reason. As the “White” armies closed in around the Bolshevik regime, the Allies had begun landings at the ports (intended to secure munitions from the Germans, but the Bolsheviks were sure this was an “imperialist” conspiracy against them), and powerful voices among the Bolsheviks’ German sponsors were expressing buyers’ remorse.6

The Bolsheviks were frightened that if the Tsar fell into the hands of the “Whites”, he could serve as a rallying point for the nation. There had been indifference when the Tsar abdicated in March 1917. A year later, when hopes about an alternative had given way to the concrete reality of what that was—savage repression, official theft, and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which was outright treason in the view of most Russians—popular sentiment in favour of the monarchy was detectably surging.7

There was also opportunity, however. Had the Bolsheviks wanted to move the Imperial Family to Moscow, they could have done so; their own officials moved back and forth easily enough with large cargos from Ekaterinburg, where the Royal Family were imprisoned in Ipatiev House.8 The reality was that in the chaos, the Bolsheviks could make the statement in blood they had long contemplated.9

The Bolsheviks initially tried another deception operation, sending letters to the ex-Tsar, beginning on 19 or 20 June 1918, which claimed to be from supporters with an escape plan. The idea was to have the Imperial Family climb out of a window late at night, after which they would have been “disappeared”. The first hitch in this plan was that the Emperor insisted that the loyal staff who had stayed with them must also be rescued; since the Bolsheviks needed these staff as the witnesses to the “disappearance”, this was an issue. For reasons unclear, the planned “rescue” by the Cheka never took place, despite the Family waiting up all night by the window in the master bedroom of Ipatiev House on 26-27 June. Nicholas transmitted a note to his non-existent would-be-saviour the next day to the effect he was not prepared to escape; the Emperor had resisted all scheming since being deposed, and his one attempt to dabble in such things convinced him this was an error.10

The last letter, in the first week of July, was signed ostensibly by Prince Vasily Dolgorukov and Count Ilya Tatischev, Generals in the Imperial Army and devoted monarchists who had insisted on accompanying the Family from their first house arrest in Tsarskoye Selo to Tobolsk when they had been sent there by the Provisional Government in August 1917, and stayed on when Lenin had the Family deported to Ekaterinburg in late April 1918. Proving that the letters were provocations, Dolgorukov and Tatischev had been arrested before early July 1918,11 and on 10 July the two men were shot by a Chekist death squad in the Ivanovskoye Cemetery in Ekaterinburg. The Bolshevik who fired the fatal shots was the 23-year-old Grigory Nikulin, a participant in the murder of the Tsar and his family.12

Before moving against the Imperial Family, the Bolsheviks had carried out two further murders. The move to Ekaterinburg initially split the Romanovs up for a month: Nicholas, Empress Alexandra, and one of their daughters, 19-year-old Maria, arrived at Ipatiev House on 30 April 1918; the other four children—Olga (22-years-old), Tatiana (21), Anastasia (17), and Alexei (13)—arrived on 23 May, having remained with Alexei, who could not be moved because he had a haemophilia attack. The four Romanov children were transferred from Tobolsk to Ekaterinburg on a steamer by their carers, Baltic sailors Klimenty Nagorny and Ivan Sednev. Nagorny was particularly devoted to Alexei, and became one of the Tsesarevich’s few friends, since everyone else was excluded by the protective bubble imposed around Alexei because of his haemophilia. Having voluntarily stayed with the Imperial Family, on 24 May the sailors were made to sign a receipt affirming they wished “to continue to serve under the former Tsar Nicholas Romanov”. In effect they had signed their own death warrant. At Ipatiev House, Nagorny and Sednev worked to protect the Family from the abuse and harassment of the Red Guards, among other things scrubbing the obscene graffiti off the walls. It was Nagorny’s objection to a Bolshevik soldier stealing “the little gold chain from which the holy images hung over the sick bed of the Tsesarevich” that led to his and Sednev’s arrest on 28 May, just five days after their arrival in Ekaterinburg. On 28 June, Nagorny and Sednev were taken to a wooded area near the railway station and shot in the back for “betraying the cause of the Revolution”, i.e. remaining loyal to the Romanovs. Their decaying, unburied bodies were recovered by the “Whites” a month later and buried in the local churchyard.

At 1:30 on 17 July 1918, the Bolshevik guards had Dr. Eugene Botkin, the Romanovs’ physician, wake the Emperor, telling him that disturbances in the city meant the Family had to be moved—for their safety. At 2:15, the Imperial Family was gathered in the basement, and the leader of the Bolshevik killer squad, Yakov Yurovsky, read out a pseudo-legal death sentence to the Emperor, who retained the composure he had since his abdication. Yurovsky shot Nicholas in the chest at point-blank range. The Tsarina was then shot in the head. Over the next ten minutes, a frenzied, drunken massacre was carried out of the five children. Particularly horrific was the fate of Alexei, butchered by Pyotr Ermakov, before Yurovsky shot the boy in the head. The four domestic staff—Botkin, lady-in-waiting Anna Demidova, footman Alexei Trupp, and cook Ivan Kharitonov—were also slaughtered, as was Tatiana’s bulldog, Ortino (or Ortipo).13

The bodies were stripped, robbed, the girls’ bodies molested, and they were all thrown down an abandoned gold mine near the village of Kiptiaki, ten miles north of Ekaterinburg. The Four Brothers mine, known now as Ganina Yama, transpired to be too shallow, and the Bolsheviks could not afford for the bodies to be discovered and become objects of worship, as martyrs so often did in Russian Orthodoxy. In the early morning of 19 July, the Bolsheviks returned, carrying vast quantities of sulphuric acid and kerosine, to dig up the bodies to throw down a deeper mineshaft, but the truck got stuck in the mud heading towards Moscow. Yurovsky and his gang settled for burying them in a shallow grave nearby, after pouring acid on their faces to disfigure and disguise them.14

THE SECOND MASSACRE OF JULY 1918

Twenty-four hours after the massacre of the Imperial Family, in the early hours of 18 July 1918, ninety miles north in Alapayevsk, the Bolsheviks murdered eight more people, six of them Romanovs. The two women and six men, sleeping at the Napolnaya School that served as their prison, were told they were being moved as the “White” Armies approached. The Bolsheviks even staged an attack on the school by men dressed as “White Guardists”.15 This lie soon unravelled, and, unlike the Tsar and his children, everyone in Alapayevsk knew as they were being led into the forest on horse-drawn carts that they were being taken to their deaths.16

Grand Duchess Elisabeth Feodorovna (“Ella”) was the older sister of the Tsarina. She had been married to Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, the slain Tsar’s uncle.17 After Sergei was murdered by terrorist-revolutionaries in February 1905, Elisabeth had founded and joined the Marfo-Mariinsky Convent. On this night, it was this defenceless woman, dressed in her nun’s habit, that the Bolsheviks attacked first, bludgeoning her with the butts of their rifles and then throwing her down a mineshaft, along with a Sister from her convent, Varvara Yakovleva. The Bolshevik killers, led by Vasily Ryabov, then threw the six men in, too.18

The six men were:

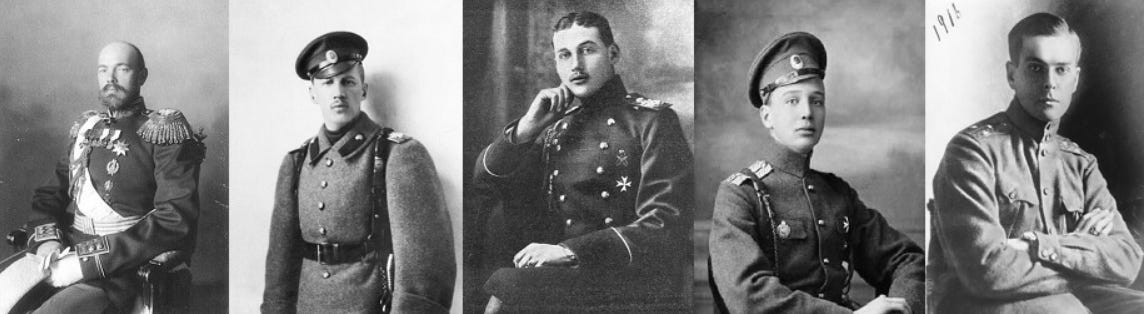

Princes Ioann Konstantinovich (32), Konstantin Konstantinovich (28), and Igor Konstantinovich (24), three brothers who had served in the Army during the Great War. Ioann and Igor had been especially decorated for service, and Igor particularly badly wounded by German gas. They were sons of Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, a grandson of Nicholas I, who had nine children before he died of illness in June 1915.19 Konstantin Konstantinovich had been very friendly with Elisabeth.

Prince Vladimir Paley, a 21-year-old20 cousin of the three Princes, the son of Grand Duke Pavel Alexandrovich, another uncle of Nicholas II’s. Paley was a talented poet, which got him into some trouble with the Provisional Government when he wrote one against Minister-President Alexander Kerensky.

Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich, 48, a cousin of Nicholas II.21 Sergei Mikhailovich had been the head of artillery during the Great War and worked closely with the Emperor once he took personal charge at the Stavka, but Sergei was disliked by the Empress and since she—and Grigori Rasputin—had the commanding influence on personnel decisions by the end, Sergei was unable to have much impact on war policy.

Sergei Mikhailovich’s secretary, Fyodor Remez, was the final victim.

It is known that Sergei Mikhailovich had tried to resist the Bolsheviks until they shot him in the arm. The traditional story thereafter is that the eight victims were thrown into the mineshaft in Verkhnyaya Sinyachikha in the hope that they would drown and when they did not, and began singing an Orthodox hymn, “Save Lord, Your People”, the Bolsheviks threw in grenades, which also did not work, finally resorting to filling the shaft with burning wood and suffocating the victims with the smoke.22

However, later evidence from the site and forensics casts doubt on this. It was a fifty-foot drop, for one thing. There does not seem to have been much water at the bottom. From the position of Elisabeth’s body, it seems she was very likely dead before she was thrown down. Sergei was shot in the head before he was dumped in the mineshaft. The other Romanov bodies all showed trauma marks to the head that were probably fatal. It is possible Yakovleva survived for a short time, and Remez certainly did survive the fall—his body was found “along the track which transported the coal to the engine room”, where he had evidently crawled before dying. The Bolsheviks had wanted the Romanovs dead; they were much less attentive with the other two.

AN ANTI-MONARCHIST MASSACRE WITH NO ROYALS

The Bolsheviks massacred ten people on 4 September 1918 in the forests around Perm, close to where Grand Duke Mikhail and his secretary were murdered. The two known victims are Ekaterina Schneider (“Trina”), the elderly Russian language tutor to the Tsarina, and Countess Anastasia Hendrikova (“Nastenka”), the 31-year-old maid of honour to the Tsarina. Both women had insisted on making the journey from Tobolsk to Ekaterinburg, but when they arrived they were separated and put in Perm Prison, alongside Dolgorukov, among others. The other eight victims of this atrocity had also been inmates at the prison; it is unclear if they had ties to the fallen Court.

There would have been an eleventh victim had Aleksei Volkov, the Tsar’s former valet, not realised what was going on as the group was being led into the forest and fled through the trees, a daring thing for a man of nearly sixty. Despite the Bolsheviks firing after him, Volkov survived. Volkov joined the resistance and managed to escape when it was defeated, eventually settling in Scandinavia, where he died in 1929.

THE FINAL MASSACRE

The Bolsheviks killed the final four Romanovs, all of them Grand Dukes in their fifties, on 28 January 1919, at the Peter and Paul Fortress in Petrograd (Saint Petersburg).

The four were:

The Tsar’s uncle, Grand Duke Pavel Alexandrovich.23 Pavel’s son, Prince Vladimir Paley, was among those cut down alongside Elisabeth in Alapayevsk on 18 July.

Grand Duke George Mikhailovich and Grand Duke Nicholas Mikhailovich (“Bimbo”), cousins of Nicholas II, who had already lost a brother to the Bolsheviks, Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich, killed in the Alapayevsk massacre.24

Grand Duke Dmitri Konstantinovich, a first cousin of the three brother Princes massacred in Alapayevsk,25 was also a paternal great uncle of Britain’s Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, who died last year.

The four Grand Dukes were arrested in July 1918 and were supposed to have been exiled from the old capital (Lenin moved the capital from Petrograd to Moscow in March 1918). But they were transferred to the Peter and Paul Fortress in August 1918 and stayed there. The context for the murder of the four Grand Dukes was the official—that is, the publicly declared—onset of the Red Terror.26

On 17 August 1918, Moisei Uritsky, the Cheka chief in Petrograd, who had resigned over Brest-Litovsk and re-joined the Central Committee after the Czech mutiny two months later, was assassinated by a young military cadet Leonid Kannegisser,27 and two weeks later, on 30 August, Fanya Kaplan,28 a member of the Leftist anti-Bolshevik Socialist-Revolutionaries (SRs), had tried to kill Lenin himself, seriously wounding him with two bullets during a factory visit in Moscow. In response, on 2 September, the de jure Bolshevik head of state Yakov Sverdlov,29 issued “The Red Terror Order”, which was published in official regime newspapers, and on 5 September this was added to by a decree from the Council of People’s Commissars, the Bolshevik regime’s executive body known by its acronym “Sovnarkom”, “to isolate the class enemies in concentration camps”, to “shoot to death every person close to” organisations resisting Bolshevik rule, and to publish all names of those killed.30

In Severnaya Kommuna (Northern Commune), on 6 September 1918, the Bolsheviks published a list of the hostages the regime held who would be slaughtered if any further senior Bolsheviks were killed; the Grand Dukes’ names were at the top of the list, despite them having no connection with the SRs or anyone else engaged in the struggle against the Communists.31 All the same, it was a clear indicator that the four men were in the sights of the Bolshevik death squads.

As Peter and Paul Fortress massacre took place after the issuance of the Red Terror Order, it is the one that most closely resembles a “normal” revolutionary atrocity: the Bolsheviks issued a public notice about their deed. That said, the killings were distinctly unusual in at least two senses.

First, the killings were not even nominally carried out for “crimes against the people” or other domestic motivations revolutionaries usually cite when eliminating the members of the old order. The stated reason for killing the Grand Dukes was as revenge for the deaths of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, German Communists who led a revolt in Berlin against the Weimar government and were killed on 15 January 1919 after the Freikorps suppressed it.32 The Bolsheviks did not see themselves or their Revolution as Russian; it was a global movement that happened to have established its first toehold in Russia. There was no patriotism in Lenin, not even deep down: his whole program was to smash Russia to pieces so he had tabula rasa to implant his Revolution, which would then be taken to the world.33

Second, while one could describe the process by which the Grand Dukes were put to death as a “firing squad”, it was, as with all Chekist operations, the work of a “gallery of fanatics and alcoholics in a chamber of horrors”.34

The Peter and Paul Fortress massacre was, once again, carried out in the early hours, just after midnight 27-28 January. The prisoners were woken, made to remove their shirts, and taken out into the courtyard. Nicholas Mikhailovich was carrying his Persian cat and would hold onto it until the end.35 Pavel was so ill he had to be carried on his stretcher into the grounds of the Fortress; he was shot first, while on his stretcher, and dumped in the open pit the Bolsheviks had dug in front of the Cathedral, which already contained thirteen bodies.36

Seeing this, the other three began to pray as they were ordered to stand before the pit. Dmitri is supposed to have said, “forgive them; for they know not what they do” [Luke 23:34]. Dmitri was extremely pious and completely unhypocritical about it; unlike most Grand Dukes, he never had a mistress, for example. After his military career, Dmitri lived a quiet and frugal life, devoting much of his income to the building and upkeep of churches. Dmitri never held a political role and, by 1919, he was totally blind in one eye and the other was not much better. Merely being helpless and innocent of any intent against the Soviet regime never saved anybody from the Communists, though, and Dmitri was mown down with the other three into the ditch.37

THE FATE OF THE SURVIVING ROMANOVS

At the time of the Bolshevik coup in November 1917, there were fifty-two Romanovs in Russia.38 A few of the other thirty-four had managed to get to safety abroad by late 1918, before half of them were rescued in a single British rescue mission in early 1919.

Dmitri Konstantinovich’s nephew, Prince Gabriel Konstantinovich—brother of Ioann, Konstantin, and Igor, killed in Alapayevsk—was probably the luckiest of all, beneficiary of that rarest of things: an act of mercy from Lenin. Imprisoned with his uncle and the other Grand Dukes at the Peter and Paul Fortress, Gabriel’s wife happened to be friendly with the wife of the writer Maxim Gorky, and Gorky lobbied Lenin directly to let Gabriel go, which, amazingly, Lenin did. In the nick of time, Gabriel was able to flee via Finland and Germany to Paris.39

Around the same time, in December 1918, Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna the Younger, a cousin of Nicholas II (and of Britain’s Prince Philip),40 managed to escape into Romania, where she was related to the King by marriage. Maria had worked—as most of the Romanov women had—as a nurse during the Great War, before needing to lie low after the fall of the Tsar. Maria escaped with her husband, Sergei Putyatin, a minor Prince she had married in late 1917; his brother, Alexander Putyatin; and her son, Prince Roman Sergeievich Putyatin, whose baptism ten days after his birth took place in Petrograd hours after, a thousand miles to the east, Maria’s half-brother, Prince Vladimir Paley, and her aunt, Grand Duchess Elisabeth, had been done to death in Alapayevsk.

Maria’s younger brother, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, survived because he was not in Russia when the revolution broke out: he had been banished for his involvement in the murder of Rasputin in December 1916. Dmitri spent a few months in Britain before joining his sister, with whom he had always been close, in Paris,41 where his affair with fashion designer Coco Chanel became something of an international sensation.

Also in December 1918, Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich, the brother-in-law of the last Tsar, managed to leave Russia, and also headed to France, where he arrived in late January 1919, hoping to convince the Allies to maintain an interest in Russia even though the Great War was over; he was to be disappointed.42

The British, feeling justly guilty about the way they left the Tsar and his family to the Bolsheviks, decided in early April 1919 to prevent the same fate befalling the rest of the Romanovs, specifically Nicholas II’s mother, the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna. Maria had been the Princess Dagmar of Denmark before she married Alexander III, and was the sister of British Queen Mother. HMS Marlborough arrived at Yalta 7 April 1919; when it left on 11 April, it carried seventeen Romanovs into permanent exile.43 There was Grand Duke Nikolay Nikolayevich (“Nikolasha”), Nicholas II’s cousin,44 who had been the Imperial Army’s commander-in-chief before Nicholas took over in September 1915. Nikolay’s wife, Princess Anastasia (“Stana”) of Montenegro was on board, as was her sister, Princess Militsa, and her husband (Nikolay’s younger brother), Grand Duke Peter Nikolayevich. The Montenegrin sisters had been branded “the Black Crows”, blamed by many Royalists for introducing Rasputin to the Court.45 There was the Nicholas II’s sister, Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna, whose husband, Alexander Mikhailovich, had already left Russia to make his appeal to the Allies in Paris. Xenia had with her five of her six sons. And there was Prince Felix Yusupov, the lead conspirator in the Rasputin murder, along with his wife, Princess Irina Alexandrovna (the only niece of Nicholas II), and his parents, Felix’s mother, Princess Zinaida Yusupova, and his father, Count Felix Yusupov. Another three-dozen Russians were taken to safety aboard the Marlborough, a total of about fifty.46

Some refused to get aboard the Marlborough. One was Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, Nicholas II’s other sister, who moved for a while to “White”-held territory in the Caucasus, before deciding to leave just before the Novorossiysk disaster in the spring of 1920. Olga joined her mother in Denmark in April 1920.47

Another who did not board the Marlborough, perhaps because she could not due to ill-health, was Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna the Elder (“Miechen”), a German Princess whose husband until his death in 1909 was one of Nicholas II’s uncles.48 Remaining with Miechen was one her sons, Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich, a first cousin of Nicholas II.

Andrei and his brother, Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich, had been arrested by the Bolsheviks in early August 1918 and sent down to Pyatigorsk, where they were placed under house arrest in a hotel, along with Andrei’s aide-de-camp, Feodor Von Kube. The brothers escaped,49 and with Von Kube fled into the mountains, where they hid until by a stroke of fortune they were picked up by the “Whites”, in the form of Andrei Shkuro’s Kuban Cossack unit, which was nominally under the authority of General Anton Denikin’s Volunteer Army.50 Reunited with their mother at Anapa in the autumn of 1918, Miechen prevented her sons joining the Volunteers—all of the Romanovs considered it wrong for them to be involved in the civil war—even as she hoped the “Whites” would prevail. Boris and the last of his mistresses, Zinaida Rashevskaya, quit Russia in March 1919, and Miechen and Andrei finally took a boat out in February 1920, a month before the evacuation of Novorossiysk, which signalled the final strategic defeat of the “White” cause.51 Miechen did not last long in exile, dying in France in September 1920.

The most prominent of Miechen’s sons, Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich, had briefly hung around in Russia after the “February Revolution” in the hopes that he would be named Regent of the Tsar’s office by the Provisional Government. When it became clear this would not happen, and that Kirill might be in some danger of arrest, he fled abroad to Finland in June 1917 with his wife, Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna.52

The Romanovs who managed to escape took their place among a million-and-a-half Russians driven from their homeland by the Bolsheviks. Until the mid-1920s, the military component—the remnants of the “White” Army under Denikin’s replacement, General Pyotr Wrangel—stayed in Jugoslavija,53 but by the numbers the main émigré centre in Europe was always France, specifically Paris. Significant though smaller numbers settled in Britain and the United States. There were isolated Russian “colonies” dotted around the Continent, in places like Germany, but they were—contrary to some myths—insignificant in scale and in the impact they had on émigré politics. The Bolsheviks, ever-paranoid, heavily surveilled and infiltrated the émigré population from early on, taking advantage of their yearning to get home by running deception operations like SINDIKAT and TRUST to lure their leaders and other daring types to their deaths in the Soviet Union with the mirage of underground resistance movements.54 By the end of the 1930s, these “White” plots were finished. In their desperation, some émigrés saw Hitler’s tanks in 1941 as the way back, though Denikin—who had actually fought the Bolsheviks, virtually alone when the world decided it had no interest in his cause—told them long before Operation BARBAROSSA began that such a thing was evil and treasonous.55 Fantastical conspiracies for removing the Bolsheviks and returning to Russia would torment the émigrés right to the end of the Cold War, as would the Soviet secret police.

INVESTIGATIONS

Ekaterinburg fell to the Czechs on 25 July 1918 and the Russians who came in with them immediately made for Ipatiev House. Finding it empty and in disarray, since it had been ransacked and looted by the Bolsheviks after the massacre,56 an inquiry began, but six months slipped away before proper work began. In January 1919, the Supreme Ruler of the of the All-Russian Government (“Directory”) headquartered in Omsk, Admiral Alexander Kolchak, appointed his chief-of-staff Mikhail Diterikhs to undertake an investigation into what happened to the Imperial Family. Diterikhs, who would later lead the final pocket of “White” resistance—begun in 1922, long after the civil was over, and destroyed in June 1923—was unqualified for the position, and, in February 1919, Kolchak replaced him with Nikolai Sokolov, a lawyer from Siberia, who worked under Diterikhs’ oversight.57

By the time Sokolov began his work, the bodies from Alapayevsk had already been found (in October 1918) and the bodies of Hendrikova and Schneider in Perm soon would be (in May 1919). The bodies of little Alexei and his sister, Maria, were only found in 2007; the rest of the Imperial Family were only located, at long last, in 2020. The final resting place of the Tsar’s brother, Mikhail, and his trusty British secretary, remains a mystery.

The Sokolov Commission interviewed the available witnesses—the Tsesarevich’s English tutor Charles Sydney Gibbes, who became an Orthodox monk after returning home to Britain, and the boy’s French tutor, Pierre Gilliard, as well as Gilliard’s wife, the governess for one of the Tsar’s daughters (Anastasia), Alexandra Tegleva—and examined the available massacre sites. Sokolov discovered Ganina Yama, where the Imperial Family had initially been dumped: he found the Romanov property the Bolsheviks had not felt worth looting, like spectacles and corsets, as well as a finger, believed to be the Tsarina’s, severed so the Bolsheviks could steal a ring, plus Botkin’s false teeth, and the corpse of Anastasia’s Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Jemmy,58 which Yurovsky’s gang had not bothered to move from the bottom of the mine shaft.59 Sokolov and the “Whites” had to abandon Ekaterinburg on 15 July 1919, so he never had time to find the burial site on the Koptyaki Road.60

The Bolsheviks continued to officially claim that the Tsarina and the children were still alive until 1926, and only admitted what they had really done at that point because Sokolov’s findings, the evidence he had gathered at the scene and testimony from witnesses, had been published as a book in France in 1924,61 and parts were then translated into other European languages and circulated. Sokolov’s account was, in all essentials, correct, and it was the only real information available about what had happened at Ekaterinburg for over a century—even the Bolshevik account drew on Sokolov’s work.62 The tragic thing for Sokolov was that the monarchist émigrés wanted to believe the lie, so they ostracised him. The most prominent surviving Romanovs, the Dowager Empress and Nikolasha, refused even to meet Sokolov, who died alone and impoverished in November 1924.63

A NOTE ON THE JEWISH QUESTION

There was an immense symbolism in what the Bolsheviks did to the fallen Tsar and his children; it foreshadowed the formal onset of the Red Terror and it took to a popular audience the notion that governments with utopian projects for the betterment of mankind had a moral duty to eliminate people who had committed no crime, but who were, simply by their existence, in the way.64 Hitler would become the Bolsheviks’ most infamous imitator. In the scales of the Bolshevik slaughter, however, the Romanovs were a drop in the ocean, and the reaction inside Russia largely reflected this.65 The most important practical impact was supercharging an antisemitic trend that identified Jews with the Bolsheviks.

One of the lead architects of the massacre (Sverdlov) and its lead implementer (Yurovsky) were Jewish,66 and the Bolshevik regime highlighted their role.67 Sverdlov became a cultic, saint-like figure in Bolshevik propaganda—Ekaterinburg was even renamed Sverdlovsk in his honour—and an account of the atrocity was put out under Yurovsky’s name. This was against a backdrop where the “Judeo-Bolshevik” conspiracy theory had gained some purchase: some of the most visible senior officials in the Bolshevik regime were Jews,68 and in the Cheka—the institution by which most had personally experienced the regime—there was a disproportionate number of Jews.69

It should be noted that the “Whites” did not, contrary to legend, have antisemitism as a pillar of their ideology: there were Jewish members of the movement from the very beginning and the “White” political leadership was mostly Kadets, one of the few pre-revolutionary liberal parties that had made Jewish equality one of its defining issues.70 Nor, as is commonly believed, had the Tsarist government produced and disseminated The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,71 which had very minimal reach in pre-1917 Russia—not that this particularly bears on the “Whites”, since the leadership and declared political program was the restoration of the elected Constituent Assembly the Bolsheviks had disbanded, not the monarchy.72

Antisemitism was widespread among the Russian population, though, and the massacre of the Imperial Family contributed to a politicised inflammation of it. It was in this atmosphere that the most intense wave of pogroms took place from mid-1919 to early 1920, many of them by nominal “White” units, especially in Ukraine. Denikin and Kolchak issued repeated public orders demanding the protection of Jews, but the “White Army” was not an army in a conventional sense and their practical authority over the various armed formations was patchy.73 As such, the “White Terror” not only was not but could not be a systematic phenomenon, and simply cannot be compared, in quantity or quality, to the Bolshevik Terror.74

The most visible case where the massacre of the Imperial Family radicalised a “White” commander was Diterikhs, who had overseen the investigation in 1919. By the time Diterikhs led his Vladivostok-based uprising in 1922-23, he was as close as any “White” General would get to the Bolshevik propaganda image of the “Whites”, modelling his regime on a medieval Orthodox polity, and in his memoirs afterwards he reported as fact the most lurid rumours about the ritual murder of the Romanovs and stressed at every turn his conviction that Jews were responsible.75

For people whose world had come crashing down around them, such a seismic event must have a cosmic significance and in a Christian culture the figure of cosmic evil is the Jew.76 Such an idea is, in a paradoxical sense, a form of solace: it gives order and meaning to the world, a much more satisfying explanation for the Bolshevik triumph than the chaotic confluence of events that had actually brought it about: the domestic confusion that led to the Tsar’s abdication, the intelligentsia’s inability to free itself from its fatal attraction to terrorist-revolutionaries that collapsed the Provisional Government, the machinations of the German Foreign Ministry,77 the Allied refusal to see the Bolsheviks per se as a danger, and the lack of effective communications between Denikin and Kolchak.

LENIN’S RESPONSIBILITY

The Bolsheviks admitted to killing the Tsar two days after it happened: Sverdlov gave the official version to Izvestiya and Pravda on 19 July 1918, presenting it as a local decision taken by the Ural Executive Committee (Uralispolkom) in something of a panic as Nicholas tried to escape while the Czech Legion and Russian anti-Bolshevik forces approached Ekaterinburg.78 This is obviously false in that it concealed the murders of the Empress and the children, but it is false in the smaller details as well: the decision was neither local nor spontaneous, but entirely centralised and premeditated. Nonetheless, the Communists and Soviet-sympathetic historians always tried to distance Lenin from the decision, right down to the end of the Soviet Union and, indeed, beyond.79

It is true that the document Yurovsky read to the Emperor shortly before he shot him was officially issued by Uralispolkom, and it is absolutely true that one of the most enthusiastic supporters of the massacre option for dealing with the Imperial Family was Filipp Goloshchyokin, a military commissar of the Uralispolkom. But Goloshchyokin had no authority to act alone: he had been to Moscow, arriving on 3 July 1918, where he had been given an order by Lenin to carry out the killings.80 Goloshchyokin took this death warrant for the Emperor back to Ekaterinburg on 12 July,81 where he informed the Uralispolkom that it had been delegated to decide on the details of how and when—hence the document Yurovsky had.82

It should be self-evident that Bolshevik historiography is nonsense: any official who took a decision of this magnitude without checking with the Centre would be putting themselves in mortal danger. Insubordination was not a problem from Uralispolkom: zealots the local leadership might have been, even by Bolshevik standards, they were “dedicated party men who … kowtowed to a very clearly defined party hierarchy”. Their ideological devotion to the Party is also why none of them revealed later on who really made the decision: these men had “no difficulty in taking personal responsibility … in order to keep the revered leader’s hands clean”.83

The reality is that the decision to murder the Emperor and his family was an unusually personal decision from Lenin, even within the Bolshevik framework. The decision was not put before the full Central Committee to be rubber-stamped. Officially, seven of the twenty-three Central Committee members were present when the decision to murder the Imperial Family was transmitted to Goloshchyokin, nicknamed “the eye of the Kremlin” because of his close relationship with the Centre. There was no debate and it had been decided on in advance of this meeting by just three of them: Lenin, Cheka (secret police) chief Felix Dzerzhinsky, and Sverdlov.84

This was in effect an “off-the-books” decision, taken by a cabal around the leader and then presented as a fait accompli to a rigged assembly, not unlike how Usama bin Laden orchestrated the 9/11 attacks. This is why—not even mentioning the purging and hiding of Soviet documents—it is so disingenuous when Lenin is exculpated by pointing to the lack of official documentation showing his responsibility. Yet, to this day, no less a figure than Vladimir Soloviev, who led the Investigative Commission into the Romanov murders after the collapse of the Soviet Union, takes such a line. The argument parallels that made by Turkey in the case of the Armenian genocide, and is about as convincing.

What makes this documentary literalism so unforgiveable is that it is not an isolated case: it is part of a systematic pattern, well-understood by historians for a long time now, wherein Lenin went to great lengths, while speaking in the abstract of his support for the Red Terror, to keep his name off the documents authorising any specific instance of it. The myth that Dzerzhinsky was the architect, rather than administrator, of the Terror was created in Lenin’s lifetime by the man himself.85

The most that can be said in Lenin’s “defence” is that he was being pressured by the Ural Regional Soviet (URS) to give the order for the massacre: the URS had voted unanimously on 29 June 1918, in a meeting at the Amerikanskaya Hotel (American Hotel) in Ekaterinburg, to “liquidate” the Tsar and his family.86 To accept this kind of “distancing”, however, would mean believing Lenin could be forced into decisions by underlings, and there is simply no evidence for this. Lenin never rushed decisions, and, despite his in-person eruptions of fury, he never took decisions impulsively: he coldly studied matters and then gave his orders.

A tell-tale piece of evidence that the massacre of the Imperial Family came from the Centre is that, on 4 July 1918, control of Ipatiev House was handed over from the Ekaterinburg Soviet to Lenin’s Cheka under Yurovsky.87 Likewise indicative is that the messaging, both before (with Lenin’s trial balloon statement to Nashe Slovo) and afterwards, was entirely centralised.88

The decisive evidence, however, comes from Leon Trotsky. Shortly after the massacre in Ekaterinburg, Trotsky spoke with Sverdlov, with whom he was in something of a rivalry for the position of second-most powerful man in the regime. Trotsky reports that Sverdlov bluntly stated when asked who made the decision: “We made it here. Ilych [Lenin] believed that we shouldn’t leave the Whites a live banner to rally around”.89

Trotsky adds in his own voice great praise for Lenin’s “characteristic” decision, which understood all of the issues at stake: “the decision was not only expedient but necessary” to show the world that the Revolution would “fight on mercilessly, stopping at nothing”, “to frighten, horrify, and dishearten” the Russians resisting the Bolsheviks, and “to shake up our own ranks, to show them that there was no turning back”.90 Trotsky was not wrong: by staining the members of the Bolshevik Party with the blood of their Emperor and his children, they had trapped them; they now had nowhere else to go, and would stand or fall with the Bolshevik leadership.

References

“How unconcerned [Mikhail] was with political events may be gathered from the fact that a few days after turning down the throne, he appeared before the astonished officials of the Petrograd Soviet with a request for permission to hunt on his estate.” See: Richard Pipes (1990), The Russian Revolution, pp. 746-47.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 764.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 764.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 765.

“Whites” is a propaganda term the Bolsheviks affixed to the Russian resistance, falsely trying to associate it with the Bourbon Restoration. None of the “White” commanders were personal monarchists and the Volunteers’ declared political program was to re-open the democratically elected Constituent Assembly the Bolsheviks had closed down at its first meeting in January 1918.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 746.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 747.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 787.

“Revolution is pointless without firing squads”, Lenin had said, and he had written as far back as 1911 that for his Revolution to make its point and succeed, “It is necessary to behead at least one hundred Romanovs.” He had been delayed in this policy after the November 1917 coup by prudential considerations. See: Simon Sebag Montefiore (2016), The Romanovs: 1613-1918, p. 636.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, pp. 766-69.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 770.

Montefiore, The Romanovs, p. 644.

Montefiore, The Romanovs, pp. 645-48.

Pipes, The Russia Revolution, pp. 777-79.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 779.

Montefiore, The Romanovs, pp. 648-49.

Sergei Alexandrovich was a brother of Nicholas II’s father, Tsar Alexander III (r. 1881-94).

Montefiore, The Romanovs, pp. 648-49.

Konstantin Konstantinovich’s fruitfulness is all the more notable since he was a tormented homosexual.

Paley was born almost exactly 125 years ago, on 11 January 1897.

Sergei Mikhailovich’s father, Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolayevich (d. 1909), was a son of Tsar Nicholas I (r. 1825-55) and a brother of Alexander II, the father of Nicholas II’s father.

Montefiore, The Romanovs, pp. 648-49.

Pavel Alexandrovich was the youngest child of the Tsar-Liberator Alexander II (r. 1855-81). Pavel’s brothers included Alexander III and Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, whose assassination by terrorists in 1905 led his wife, Grand Duchess Elisabeth, to become a nun.

George and Nicholas Mikhailovich were sons of Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolayevich (d. 1909), who was in turn a son of Nicholas I’s and a brother of Alexander II, the father of Nicholas II’s father.

Dmitri Konstantinovich’s father was Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich (d. 1892), a son of Nicholas I. One of Dmitri’s father’s brothers was Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, the father of the three Princes.

Nikolay Starikov (2018), The Liquidation of Russia. Who Helped the Reds to Win the Civil War?, p. 128.

Kannegisser was moved by both personal and political motives. Kannegisser was homosexual and engaged in a relationship with another cadet, whom the Bolsheviks had murdered, which made Kannegisser willing to take on the task of assassinating Uritsky for the Socialist-Revolutionaries (SRs). Most of the “spectacular” pre-1917 terrorist outrages, including the slaying of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, had been carried out by the SRs’ Combat Organisation, the leader of which, Boris Savinkov, proved to be the great exception after 1917 in continuing to use such tactics to try to overthrow the Bolsheviks. See: Anna Geifman (1993), Thou Shalt Kill: Revolutionary Terrorism in Russia, 1894-1917, p. 254.

Her name is often given as Fanny Kaplan in English, and she was born Feiga Roytblat to a Jewish family in Ukraine, though she had long-since ceased to use this name. Savinkov later claimed to have been behind Kaplan’s attempt on Lenin; he was, as so often, lying. See: Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 650.

Sverdlov was Chairman of the Secretariat of the Party. Sverdlov was also Chairman of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee (VTsIK). He held both posts until he died of Spanish flu in March 1919.

Vadim Birstein (2013), SMERSH: Stalin’s Secret Weapon, chapter one

The Liquidation of Russia, p. 128.

Edvard Radzinsky (2011), The Last Tsar: The Life and Death of Nicholas II, p. 329.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, pp. 396-97.

Robert Stephan (2004), Stalin’s Secret War: Soviet Counterintelligence Against the Nazis, 1941-1945, p. 72.

John Perry and Constantine Pleshakov (1999), The Flight of the Romanovs: A Family Saga, p. 209.

Montefiore, The Romanovs, p. 649.

Montefiore, The Romanovs, pp. 648-69.

Peter Julicher (2015), “Enemies of the People” Under the Soviets: A History of Repression and Its Consequences, p. 29.

David Chavchavadze (1989), The Grand Dukes, p. 151.

Maria Pavlovna the Younger was a daughter of Grand Duke Pavel, who was murdered a month after she escaped at the Peter and Paul Fortress.

Maria Pavlovna the Younger did not stay in France: she moved to America after divorcing Sergei, then went briefly to Argentina, before finally settling in Germany, where she died after the Second World War.

The November 1918 Armistice in the Great War had removed a lot of the Allied geopolitical interest in Russia, which had only ever been about preventing the Germans having so free a hand in the East that they could move forces West. It was not for safety reasons but to carry out this freelance diplomatic mission that Alexander Mikhailovich had escaped Russia—to appeal to the Allies at the Paris Peace Conference not to abandon Russia to the Bolsheviks. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson refused to meet Alexander or seriously allow the Russian Question onto the agenda at Versailles. Alexander died in France in 1933, having written two volumes of memoirs. An interesting story Alexander relays in his memoirs is, shortly after arriving in Paris, meeting his old friend Marthe Letellier and her reacting as if she had seen a ghost, since she believed he had been murdered months earlier.

Frances Welch (2011), The Russian Court at Sea: The Last Days of a Great Dynasty: The Romanov Voyage into Exile.

Nikolay Nikolayevich’s father, Grand Duke Nikolay Nikolayevich the Elder, was a son of Nicolas I’s, the great-grandfather of Nicholas II.

The epithet is sometimes given as “the Black Women” or “the Black Princesses”. See: Montefiore, The Romanovs, p. 507.

Montefiore, The Romanovs, p. 649.

Olga arrived in Denmark with her husband, Duke Nikolai Kulikovsky, a “commoner”, to the ever-lasting annoyance of the Dowager Empress. The Dowager Empress died in Denmark in 1928 and in 1948, with Stalin’s armies bringing Communism further West, Kulikovsky and Olga moved to Canada, where they died in 1958 and 1960, respectively.

Miechen’s husband had been Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, a brother of Nicholas II’s father.

How the Vladimirovichi escaped is unclear. One account has it that Andrei was sprung by a young Bolshevik guard whom Andrei had helped financially when the man was a struggling painter in pre-revolutionary Russia. The truth might well be more prosaic, and the Vladimirovichi simply took advantage of the chaos in Caucasus. See: The Flight of the Romanovs, pp. 228-29.

Shkuro, Pyotr Krasnov, and several other anti-Bolshevik Cossack commanders based in Jugoslavija were disgracefully handed by the British to Stalin in 1945 under Operation KEELHAUL; when they were shot eighteen months later by the Soviet secret police, it marked the final destruction of the “Whites”.

The Flight of the Romanovs, pp. 228-32.

The Flight of the Romanovs, p. 225. Kirill, unusually for the exiled Russian elite, initially settled in Germany, where he briefly flirted with the nascent Nazi Party and tried to claim the mantle of head of the Imperial House after a British court declared Nicholas II legally dead in 1924. The overwhelming majority of monarchist émigrés rejected Kirill’s pretentions, and he soon moved to France, where he died in obscurity in 1938.

Paul Robinson (2002), The White Russian Army in Exile 1920-1941, pp. 126-27.

Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin (1999), The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB, pp. 33-5.

Dimitry Lehovich (1974), White Against Red: The Life of General Anton Denikin, pp. 450-52.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 777.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 774.

Anastasia’s dog’s name is sometimes given as Jimmy. The other Family pets belonged to Alexei. Alexei’s cocker spaniel, Joy, was saved by his mischievousness: always running away, he had done so again in the grounds of Ipatiev House on the night the Family were murdered. One of the Bolsheviks found the dog and kept him for a while, until the “Whites” took Ekaterinburg. The dog was left behind and recovered by Mikhail Rodzianko, the former chairman of the Duma, who took Joy with him into exile and gave the animal to Britain’s King George V (r. 1910-36), Nicholas II’s cousin. Joy lived out his life at the British Court and was buried at Windsor Castle. Alexei was a lonely boy, not really allowed to mix with other children due to his station and because of his haemophilia—his parents worried about him playing with others and incurring a fatal injury—so he took solace in his pets. Alexei also had two cats, Kot’ka and Zubrovka, both of whom had to have their claws removed because a scratch to Alexei could have killed him. The cats were left at the House that night, their fate unknown.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 778.

The Romanov keepsakes Sokolov discovered, as well as his soil samples containing human tissue, were put in a box and taken with him. The “Sokolov Box” now resides in the Memorial Church of Saint Job in Brussels, and its contents are regarded as relics since the Family were made Saints by the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad in 1981 and the Church itself recommended the same in 1996, completing the process in 2000.

Sokolov’s book was called, Enquête Judiciaire sur l’Assassinat de la Famille Impériale Russe (Judicial Investigation into the Assassination of the Russian Imperial Family).

The Bolshevik account, published in Ekaterinburg, now renamed Sverdlovsk, was rather blandly entitled, Poslednye dni Romanovykh, (The Last Days of the Romanovs). See: Helen Rappaport (2018), The Race to Save the Romanovs, pp. 265-66.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, pp. 785-86.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, pp. 787-88.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 783.

Within the six-man hit squad that murdered the Imperial Family—the others were Pyotr Ermakov, Stepan Vaganov, Mikhail Kudrin, Alexander Beloborodov, and Grigory Nikulin—only Yurovsky was Jewish.

Another important player in the massacre of the Imperial Family, Filipp Goloshchyokin, was Jewish. Goloshchyokin was the administrative director of the atrocity and the man who had personally gone to Moscow to advocate for the death warrant he received from Lenin. Goloshchyokin’s lack of prominence in Bolshevik propaganda—and his disappearance after he was consumed in Yezhovshchina—seems to be part of the explanation for him having a lower register in the antisemitic polemics about the massacre of the Romanovs.

The first mass-media exposure the world had to the Bolsheviks was at Brest-Litovsk, where the delegation was led by Leon Trotsky, who was the leader of the Red Army by this stage. Two other powerful figures around Lenin, Grigory Zinoviev, the COMINTERN leader embodying the effort to bring Revolution to the rest of Europe, and Lev Kamenev, were also Jewish.

Zvi Gitelman (2015), Jewish Nationality and Soviet Politics, p. 117.

Oleg Budnitskii, 2001, ‘Jews, Pogroms, and the White Movement: A Historiographical Critique’, Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. Available here.

Charles Ruud and Sergei Stepanov (1999), Fontanka 16: The Tsar’s Secret Police, pp. 203-15.

Peter Kenez, 1980, ‘The Ideology of the White Movement’, Soviet Studies. Available here.

White Against Red, pp. 324-32.

“The White armies did, indeed, execute many Bolsheviks and Bolshevik sympathizers, usually in summary fashion, sometimes in a barbarous manner. But they never elevated terror to the status of a policy and never created a formal institution like the Cheka to carry it out. Their executions were as a rule ordered by field officers, acting on their own initiative, often in an emotional reaction to the sights which greeted their eyes when they entered areas evacuated by the Red Army. Odious as it was, the terror of the White armies was never systematic, as was the case with the Red Terror.” See: Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 792.

In The Murder of the Tsar’s Family and Members of the House of Romanov in the Urals, Diterikhs took his antisemitic thesis to absurd lengths, even in the minutiae, by, for example, renaming Yakov Sverdlov as “Yankel Sverdlov”, just in case anyone had missed that he was Jewish. [See: Wendy Slater (2007), The Many Deaths of Tsar Nicholas II: Relics, Remains and the Romanovs, pp. 71-74.] Diterikhs’ belief that the Romanovs were beheaded after death was not entirely his own invention; the rumour that the bodies had been “cut in pieces” was something believed by people not trying to create a blood libel and who had been closer to events. [See: Pierre Gilliard (2016 [originally, 1921]), Thirteen Years at the Russian Court: The Last Years of the Romanov Tsar and His Family by an Eyewitness, p. 194.]

Bernard Lewis (1987), Semites and Anti-Semites: An Inquiry into Conflict and Prejudice, p. 194.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, pp. 389-92.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, pp. 782-83.

The attempt to lead away from Lenin’s personal responsibility for the massacre of the Imperial Family is essentially the template for the school of Holocaust-denial that—while minimising the numbers and often denying gas chambers were used—admits there were massacres of Jews by the Nazis, but contends that Hitler did not know about them and/or did not order them. Probably the most (in)famous exemplar of this school is David Irving. The Nazi one-party state was modelled on Lenin’s, and the Fuhrer also borrowed from Lenin the practice of avoiding putting his name to the most incriminating documents and being conveniently absent from key meetings, such as the Wannsee Conference or Posen, where his instructions were disseminated through the Party.

Lenin had probably made the final decision the previous night, 2 July 1918. See: Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 771.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 773.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 779.

Helen Rappaport (2008), The Last Days of the Romanovs: Tragedy at Ekaterinburg, chapter ten.

The Last Days of the Romanovs, chapter ten.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 795.

The URS vote to kill the Romanovs was taken hours after the local Bolsheviks had carried out a horrifying massacre of nineteen prominent citizens. Priests, doctors, lawyers, a shopkeeper, the Russian manager of the British-owned Sysert iron works (a friend of the local British Consul Sir Thomas Preston), and a mining engineer were lined up and shot at the sewage dump half-a-mile outside the city; the survivors of the barrage were stabbed to death in a frenzy and thrown into a mass grave. See: The Last Days of the Romanovs, chapter ten.

Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 771.

On 20 July, the URS wanted to publish a gloating statement that “the ex-Tsar and autocrat, Nicholas Romanov, has been shot along with his family on July 17” on their orders [italics added]. Two notable things: they asked Moscow for permission, and Moscow said “no”, clearly because of the reference to the family. See: Pipes, The Russian Revolution, p. 784.

Edmund Wilson (1971), To the Finland Station: A Study in the Writing and Acting of History, Introduction.

To the Finland Station, Introduction.