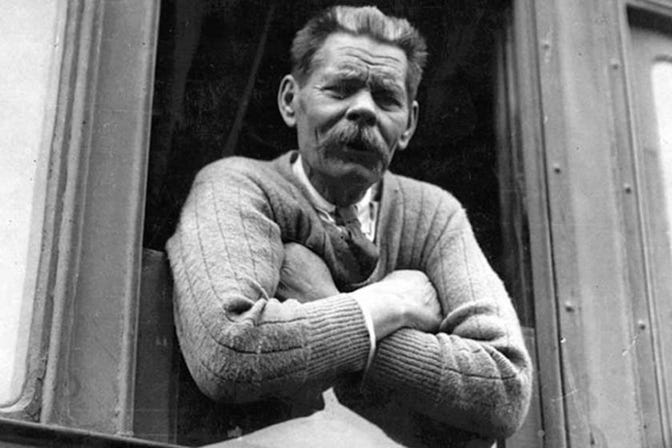

A Myth-Maker of the Soviet Revolution: Maxim Gorky

Maxim Gorky, born Alexei Maximovich Peshkov in 1868, spent an impoverished and turbulent youth in the Volga region before he became seriously involved with socialism in the 1890s. As was so often true with the revolutionary movement in the Russian Empire, the principle form Gorky’s socialist activism took was literary polemics, specifically nominal journalism and didactic plays and novels. Gorky was a declared Marxist, a virtual requirement in the Russian intelligentsia by the end of the nineteenth century, though exactly what the term meant in the Russian context was quite complicated before 1917.

After the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) split in 1903, Gorky got close to the “Bolshevik” (Majority) faction and its leader, Vladimir Lenin. It never seemed to occur to Gorky or his associates that there was a contradiction between the picture of unremitting Tsarist despotism Gorky painted in his literary output, and Gorky becoming wealthy from living the life of a public critic of the government. To the contrary, Gorky devoted significant amounts of his funds to assisting the Bolsheviks, whose cause was to destroy the system in which he thrived.

When the massive wave of terrorism in 1905 reached Moscow that December, Gorky threw himself into the revolutionary effort. A line was finally drawn and Gorky, after a brief spell in jail, went into exile. In was in the late 1900s and early 1910s that Gorky became an international “celebrity”, being feted in the United States and Europe—by people like Mark Twain—for his literature and as a political symbol of resistance to oppression.

Most of Gorky’s time abroad was spent on the Italian island of Capri, once the refuge of the Roman Emperor Tiberius (r. 14-37 AD). The lurid myths about Tiberius on Capri focus on sexual depravity and a sadistic intolerance towards dissent. Something of the same combination occurred in the hostile myths disseminated, including by Gorky, about Russian Emperor Nicholas II (r. 1894-1917), with all the legends surrounding Grigori Rasputin (and the Tsarina), and the monicker “Bloody Nicholas” that Lenin got into circulation after 1905.

It was impossible to save Russia from the terrorist revolt without some use of force and Nicholas II eventually bowed to that reality. How to politically pacify the country was a more open question. The two basic options were to try to rebuild the autocracy by imposing military rule, or to try to broaden the base of the political system by making concessions, allowing the participation of liberals and other elements of the opposition that were (theoretically) capable of turning away from the terrorists and reconciling with the State. Nicholas chose the latter option. Nicholas, unlike his father, did not enjoy being Emperor, but he did believe with heart and soul that autocracy was mandated by God. It was an incredibly painful decision to surrender powers and duties entrusted to him by the Almighty, but Nicholas was convinced this was the best way to ensure peace and security for the Russian people.

In 1905-06, Russia was refashioned as a constitutional monarchy, with an elected parliament where even revolutionaries sat, broad rights of free speech and assembly, and powerful trades unions that measurably improved the wages and conditions of the working class. In 1913, on the three-hundredth anniversary of the Romanov dynasty, Nicholas issued an amnesty that allowed Gorky to return to Russia.

In the last years of the Tsardom, Gorky worked for Bolshevik newspapers and some of his most well-known writings in this period focused on antisemitism, a serious social malady in Russia that anti-government radicals “weaponised”, as we would now say, among other things falsely presenting the pogroms against Jews in 1881-82 and 1905-06 as resulting from a deliberate State policy, the intention being to blacken the image of the Imperial Government abroad, above all in Western Europe, thereby isolating and weakening it, and improving the socialists’ chances of bringing it down.

Gorky naturally joined the “defeatist” strand of the opposition when the First World War broke out, the most extreme position, held to only by Lenin and a few others of the same orientation, which hoped for Russia’s defeat in the face of German aggression as a door-opener to a Red Russia—as it proved to be. Gorky set up an “anti-war” journal, Letopis (“Chronicle”), and did everything he could to spread demoralising propaganda in Russia’s society and army. Wartime censorship notwithstanding, the Okhranka, the supposedly suffocating Tsarist secret police, did not shut Gorky’s activities down, and the government’s loss of patience with Gorky in January 1917 proved meaningless in practice: the order terminate Letopis was never carried out as the elite debacle in responding to the military mutiny in Saint Petersburg a few weeks later led to the Tsar’s abdication.

The Provisional Government had Gorky’s support well into Alexander Kerensky’s reign, and his relations with Lenin commensurately cooled. Gorky shifted back towards the Bolsheviks after “the Kornilov affair”, Kerensky’s provocation against General Lavr Kornilov and by extension the entire Russian Army in early September 1917. Gorky’s reaction is a paradigmatic example of the catastrophic miscalculation Kerensky made in rejecting a compact with the constitutional conservatives and trying to consolidate his regime—an autocratic one by then—on the terrain of “revolutionary” legitimacy, seeking the approval of the most radical socialists and terrorists. Kerensky went so far as freeing the Bolsheviks, imprisoned after their German-backed putsch attempt in July, and even armed them against the imaginary threat of “Kornilovism”.

The radicals, however, had no interest in replacing the army as the backbone of Kerensky’s regime. What the Bolsheviks and Gorky could see was that in defenestrating Kornilov, Kerensky had left himself defenceless. The only real surprise when the Bolshevik coup took place on 7 November 1917 was that it had taken so long. This dynamic of relative moderates sincerely believing in pas d’ennemis à gauche (no enemies to the Left) and admiring the radicals—differing on tactics, but seeing the radicals as fundamentally well-intentioned and often feeling guilty they cannot match their dedication—while the radicals regard the “moderates” with contempt, to be used as stepping stones to power and then discarded, is with us still.

The apocalyptic civil war Lenin’s strategy demanded, and the Cheka Terror that was at the core of waging it, disturbed Gorky to some degree, and being associated with it even more so. A lot is made by those who praise Gorky as a literary figure, and want to defend him as more than a Party apparatchik, of tensions in his relationship with Lenin. It is said Gorky distanced himself from the new Communist government soon after its inception. It is difficult to know what to make of this.

On the one hand, Gorky retained enough official standing in late 1918 that he managed the nearest we have to an attested miracle in the historical record: he extracted an act of mercy from Lenin, convincing him to release Gabriel Konstantinovich, a great-grandson of Tsar Nicholas II, who had been slaughtered along with his wife, children, and attendants on Lenin’s orders a few months earlier. (Lenin had also murdered Prince Gabriel’s three brothers earlier in 1918 and the Grand Dukes whom Gabriel had been imprisoned with in the Peter and Paul Fortress, one of them his uncle, were massacred by the Bolsheviks in January 1919.) And as late as the spring of 1921, Gorky was close enough to Lenin to be entrusted with coordinating the propaganda to appeal for international aid to rescue the Communists from the consequences of their own economic policies, which had caused a devastating famine. Lenin saw no issue of personal responsibility, practical or moral, arising out of the people of the Volga being reduced to cannibalism, only an opportunity to begin a war against the Christian faithful.

On the other hand, Gorky began a second exile in late 1921, suggesting there was a turn in relations with Lenin. Yet even this is ambiguous. Watching Lenin subject the Socialist Revolutionaries to a show trial in the summer of 1922, Gorky was highly critical—in private. To be sure, some of Gorky’s commentary became public, and Lenin was displeased by it because it added to the growing chorus of international condemnation that ultimately forced him to commute the death sentences. But Gorky was not overtly excommunicated, nor was Gorky targeted for murder by Lenin’s intelligence services, which eliminated scores of genuine opponents of the Soviet Revolution all across Europe in the 1920s.

Initially, Gorky went to Germany, before returning to Italy in 1922. The Fascist takeover of Italy in October 1922 did not much inconvenience Gorky. What made Gorky yearn for a return to the Soviet Union, as the Communist Empire was by then, was the financial burden of upkeeping his estate. In 1928, Gorky reached out to Moscow and Joseph Stalin, Lenin’s designated and faithful heir, was thrilled at the thought of having Gorky back in the Bolshevik fold. A preliminary trip to the U.S.S.R. was organised in May 1928. While Gorky was there, Stalin was showing his devotion to Lenin’s memory by staging the hysterical show trial of engineers. There was no high moral tone from Gorky this time, not even in private; he took for granted the engineers guilty as charged, and wrote several glowing essays about his travels in Soviet Russia.

In June 1929, Gorky visited the Soviet Union again and was taken to the Solovetsky Islands to be shown around Solovki, “the Mother of the GULAG” set up on the site of a former Russian Orthodox monastery, where Lenin had gathered those whose existence annoyed him, including the SRs not selected for the show trial. By now, Stalin had expanded the concentration camp: his diligent work to actualise Lenin’s vision had exposed hosts of class enemies, counter-revolutionaries, and other degenerate elements—traitors to History, one and all. These were the kind of terms Gorky used to described the inmates he saw over three days: “counter-revolutionaries, emotional types, monarchists”. To Stalin’s delight, Gorky, one of the most renowned Russian authors in the world at the time, told a global audience of the humane and reformist nature of the GULAG archipelago:

There is no impression of life being over-regulated. No, there is no resemblance to a prison; instead it seems as if these rooms are inhabited by passengers rescued from a drowned ship. … If any so-called cultured European society dared to conduct an experiment such as this colony, and if this experiment yielded fruits as ours had, that country would blow all its trumpets and boast about its accomplishments.

Gorky was a hard-bitten man. It was this proletarian authenticity, detailed in his books about his early life, that made him such a hero to Russians, including the Solovki prisoners, who were sure that “Gorky will spot everything … He’s been around, you can’t fool him.” They were probably right about this. The Solovki camp guards had “spruced” the place up; “painted walls, planted trees, allowed husbands and wives to be together”. But the notion Gorky was deceived by a “Potemkin tour” is dubious. Perhaps all the prisoners reading their newspapers upside-down and the visitor’s book Gorky signed that had no other names in it were too subtle as signals that something was amiss. But the young boy who managed to speak to Gorky alone had not been euphemistic in his description of the cruelty and torture of camp life. Gorky relayed none of what the boy had said to his readers. The boy was shot amid the mass “executions” of “superfluous persons” that occurred soon after Gorky left, according to Alexandr Solzhenitsyn.

In 1932, Gorky took up permanent residence in the Soviet Union, an important propaganda victory for the Communists against the Fascists, and Gorky was lavishly rewarded with medals and living arrangements denied to the other inhabitants of Stalin’s big prison. The founding president of the Union of Soviet Writers, Gorky spent his last four years as a prostitute of the Soviet Revolution. Gorky, enshrined as the father of Socialist Realism in State media, was involved in defending Stalin’s escalating crimes.

Gorky returned to GULAG apologetics in 1933, organising the production of a volume, The I. V. Stalin White Sea–Baltic Sea Canal, where those who had watched Stalin’s slaves worked to death building the Belomor Canal that connected the White Sea and the Baltic recast the horrors as a redemptive story of “re-education” through labour and told of the health benefits to the zeks. It is also instructive what Gorky did not say: he never had any comment on Stalin’s terror-famine in Ukraine (Holodomor) and Kazakhstan, a crime nearly as lethal as Lenin’s Povolzhye famine. But then, Gorky was a firm supporter of collectivisation and dekulakisation, and explaining why such senseless atrocities were necessities of History was part of his job.

The GULAGs were a somewhat special case, though. There had been a couple of exposés of the Soviet concentration camps in the mid-1920s and while they never broke through to the mainstream in the West, they had been disproportionately impactful in the political sectors Moscow most cared about. Pre-emptively drowning out critical commentary on the GULAG system was enough of a priority for Moscow it was reasonable to use Gorky’s heft for the purpose. In general, “negative” refutation propaganda was somewhat beneath Gorky.

For the Soviet Empire, Gorky’s prestige was better utilised for “positive” propaganda, constructing the myth-image of a workers’ paradise beyond the Urals. An important element of this was creating the idea of a “proletarian culture”, vital and sophisticated, which the Soviet New Man basked in. Liberated from the torments of capitalism, as Gorky and his collaborators told it, the average Soviet citizen was strengthened in mind and body, educated and disciplined as no Western worker could hope to be, their individual needs met without immersion in a soulless individualism that benefited only the few. All were now dedication to the selfless pursuit of the collective good, uplifting fellow citizens and being succoured by them in turn.

That being said, there were select instances where Gorky was deputised to directly refute criticism of Stalin, albeit it was done in the guise of making a broader ideological point. One such instance was after Stalin turned away from the libertinism of the early phase of the Revolution towards a more conservative social ordering that would encourage Soviet women to produce increasing numbers of little Communists. An essay Gorky wrote in May 1934, “Proletarian Humanism”, printed simultaneously in Pravda and Izvestia, the leading propaganda organs of the Party and State, respectively, explained how Stalin’s suite of traditionalist, pro-natalist policies, which included the recriminalisation of homosexuality, was entirely different to the “capitalist” and “bourgeois” morality in the West.

Notoriously, the essay included a section where Gorky let stand the idea that eradicating homosexuals was a short-cut to destroying fascism:

[I]n the country where the proletariat courageously and successfully administers [i.e., the Soviet Union], homosexuality, which corrupts youth, is recognised as a social crime and punishable, whereas in the “cultural” country of great philosophers, scientists, and musicians [i.e., Germany], it functions freely and with impunity. There has already arisen a sarcastic saying: “Destroy the homosexuals and fascism will disappear.”

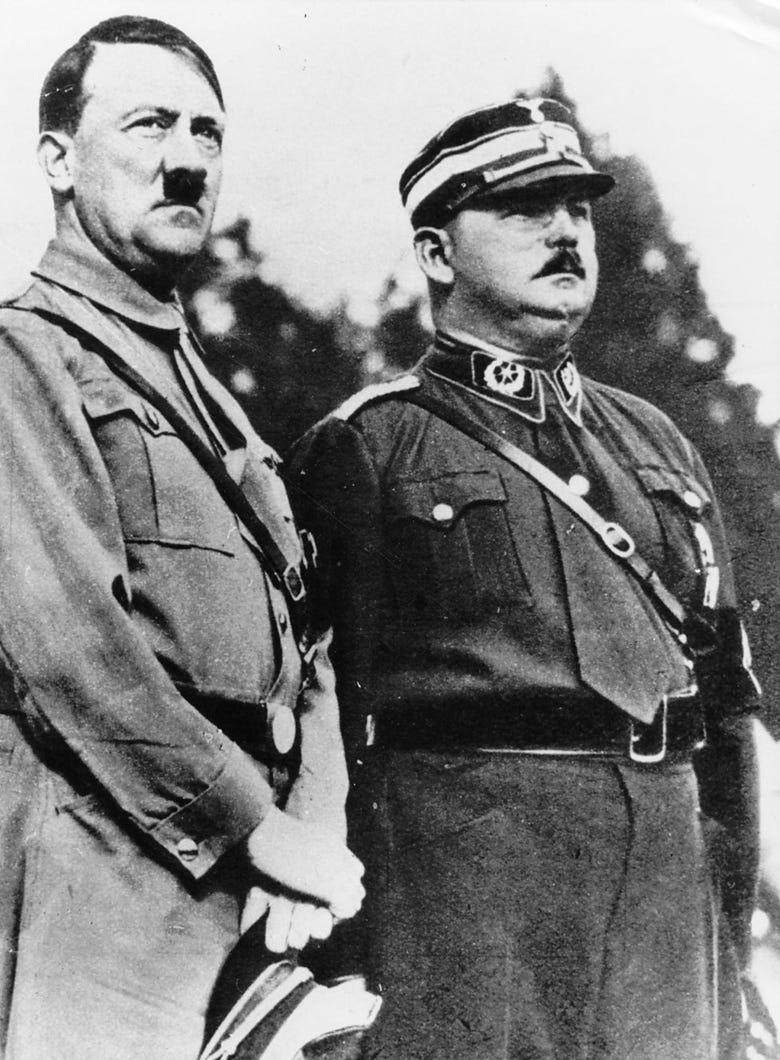

“Comrade Stalin was very pleased with that little article”, Gorky wrote to a correspondent a month later. Gorky had stayed on-message in things large and small. Associating the Nazi Party with homosexuality was not Gorky’s innovation. It was an increasingly frequent theme in Soviet propaganda through the 1930s (and by later in the decade paired accusations of spying and sodomy were being used in “judicial” settings during the purges). As with all the best disinformation, the theme contained a measure of truth. Homosexuals had a visible presence among the leadership of the Nazi stormtroopers (Sturmabteilung or SA). The SA supreme leader, Ernst Röhm, was not only open but quite flamboyant on the point. And the toleration of this went all the way to the top of the Nazi government. Adolf Hitler had defended Röhm publicly a few years earlier when his ostentatious “private” life became a subject of controversy among the Nazis themselves.

There was an ironic coda. Three months after Gorky’s article, Hitler orchestrated the Night of the Long Knives to eliminate the Redder wing of his own Party and the traditional conservatives who had never warmed to National Socialism as other than a tactical tool to restore the world they had lost with the establishment of the Weimar Republic. Röhm was the primary target, and Hitler and his Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels, explained their actions in terms that significantly recycled Soviet anti-Röhm agitprop.

The timing of Gorky’s death, in June 1936, right before the first of the Moscow Trials, has led to a lot of speculation that he was murdered by Stalin. Some of this is wilful, part of the campaign to elevate Gorky’s reputation above that of just another Stalinist hack. As with Lenin, it is said Gorky had strained relations with Stalin at the end, and, in fairness, it does seem to be true that Gorky was placed under “virtual house arrest” after the murder of Sergei Kirov in December 1934 that began the descent into Yezhovshchina. It is also true that Gorky’s son died suddenly in May 1934, and two deaths in one family, so close together and in the atmosphere of the time, is not unreasonable grounds for suspicion. But the evidence is thin. Gorky does not seem to have seriously fallen afoul of Stalin—there is no sign he was subjected to anything more sinister than some heavy-handed surveillance in his last years—and Gorky’s death per se was not unusual: he was well-known to be ill and he was 68. The son’s demise was too long before the Kirov assassination to be connected. And Stalin carried Gorky’s urn at his funeral, which is hardly dispositive, yet would have been most irregular for an “enemy of the people”.

Still, Stalin was never one to waste an opportunity: the rumours of Gorky’s poisoning were helpful in finishing with Genrikh Yagoda, the NKVD chief removed from office in September 1936. Yagoda had organised the first of the major show trials and stood in the dock at the last of them, “The Trial of the Twenty-One” in March 1938, where the most prominent victim was Right Opposition leader Nikolai Bukharin. Yagoda was “charged” with murdering Gorky via Pyotr Kryuchkov, a fellow “defendant” and Gorky’s long-time secretary, who actually had been recruited by Yagoda as an NKVD agent to keep tabs on his boss. With some encouragement from the wardens of Lubyanka, Yagoda “confessed” to organising the “medical murder” of Gorky, and Kryuchkov “confessed” to his part in the crime. They were both shot days after the “verdict” was handed down.