The Restoration of Israel and the War For Survival

Review of ‘1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War’ (2008) by Benny Morris

1948 by Benny Morris, the doyen of the revisionist Israeli “New Historians” who took apart many of the State’s founding myths, tells the story of the rebirth of the Jewish State and the Arab attempt to destroy it, the opening chapter of a war where the ending is as-yet unknown.

THE JEWS RETURN TO ZION

Morris mentions in the first chapter the foundation of the State of Israel in 1200 BC, more than three-thousand years ago, and its destruction by the Romans 1,300 years later after the Bar Kokhba Revolt, which forced most Jews into exile.1 Morris then notes that Jews began to return to the Holy Land in an organised way in the 1880s after the advent of the “Zionist” movement. Morris’ focus in a book already running to four-hundred-plus pages is very much the political and physical landscape in which the 1947-49 war for Zion takes place, so it is forgivable that Morris does not, as one eminent commentator puts it, give much of a sense of how “we get from the one case of affairs to the other case of affairs”. Still, it is worth dwelling on, all the more so since Morris’ sketch of why “Zionism” gained purchase among world Jewry when it did—European antisemitism; the rise in the nineteenth century of liberal and romantic nationalism; and “the age-old messianic dream, embedded in Judaism’s daily prayers, of reestablishing a Jewish state in the ancient homeland” [italics added]—begs a question that hangs over not only the history of these events, but the contemporary discussion.

At the present time, it has become commonplace for people to declare their opposition to the “political” ideology of “Zionism” entails no ill-feeling towards “the religion” of “Judaism”, nor Jews per se. Setting aside how frequently “anti-Zionism” is the thinnest veneer for the most blatant and ancient forms of antisemitism, this disaggregation just does not work in conception, as Morris suggests: the connection to Jerusalem and the Land of Israel (Eretz Yisrael) has been integral to Jews’ sense of themselves from the beginning, a pillar of identity that held the Jews together through the Assyrian and Babylonian captivities that destroyed so many other peoples.

The view of “religion” as a part of life separate from politics, law, and other “secular” spheres is “a strikingly odd way of conceiving the world”.2 More than odd, it is unique.3 This outlook is born of Christian theology, and even then there are two further caveats: it is confined to the Latin half of Christendom and the modern understanding of “secularism”—as the “neutral” default, with “religion” an optional, private belief—is a very recent innovation.4 For the ancients, the gods were manifest in all things: the State was ordered towards pleasing the gods, and the price the gods demanded for their protection was not that people hold the correct beliefs, but that they engage in the correct ritual practices.5 The Jews were regarded by the Romans as strange because of their insistence there was only the One God, but the premise of a particular people tied to a particular land with distinctive manifestations of their creed was strangeness within the usual bounds, and the Jewish practices—avoiding certain foodstuffs, keeping the Sabbath, even maintaining the covenant with their God via circumcision—were rather tame when set against the carry-on from other provincials, like the cross-dressing and self-castrating priests of Cybele.6

The Greek word, Ioudaismos, was coined as a defensive measure to describe Jews who held true to the Jewish way during the Maccabees’ struggle against Hellenic influence in the 160s BC, essentially as an antonym for Hellenismos, those “disloyal” Jews who had adopted Greek culture and customs. Though the word largely fell out of use among Jews for several centuries after that—the triumph of the Maccabees made it unnecessary—Ioudaismos would in time be adopted.7 What Ioudaismos signifies is not “a religion”, but the totality of what it means to be Jewish: it denotes a peoplehood—an “ethnicity” and “nation”, in modern parlance—joined in a common loyalty, to each other and a specific geography, centred on Jerusalem, united by a language of their own and a distinctive culture, set of customs, and practices, rooted in a shared history, recorded in a sacred Scripture that eventually provided the communal anchor after the destruction of the Temple.8

As Christians separated from the Jews, they would project their own radical understanding of the cosmic order onto Jews—and not only Jews. In time, the pagan peoples of the Subcontinent would have their creeds pressed into the Christian mould and be informed they were followers of the “religions” of “Hinduism” and “Buddhism”.9 The astonishing thing was that by the time the Raj ended, many had internalised this Christianisation of their world.10 The Indian Constitution defined the Republic as “secular”, with references to “Hindus” and the followers of “the Sikh, Jaina, or Buddhist religion”. There is now a backlash to this with the so-called “Hindutva” movement or “Hindu nationalism” that wants to restore Indian identity to the organic whole it was before the imposition of secularism, correctly seen as an alien import from the Christian world.11 This is the framework in which to understand the emergence of “Zionism”.

Most Jews had, against notoriously stringent pressures, refused to accept the Christian offer that Jews dissolve their distinctiveness—their attachment to one place, one people—and walk into the light of a salvation promised to the whole world. More than a millennium-and-a-half after the Emperor Hadrian had terminated Jewish self-rule, “Next year in Jerusalem” was still repeated amid the Exodus story every Passover: exile was slavery; the return to the land was freedom.12 The French Revolution was the turning point. Universalism this time came in the cloak of the Declaration of the Rights of Man: Jews were offered citizenship—as individuals. Jews could walk with the revolutionaries into the Enlightened future if they surrendered all communal claims: they were not to be tolerated as a nation; there would be no status for Mosaic law. And in the Vendée, where the blood of non-juring priests and other Roman Catholics who rejected the Revolution’s offer of liberty was thick on the ground, Jews could see their alternative. “If this seemed to some Jews a very familiar kind of ultimatum, then that was because it was.”13 This was not the interpretation of all Jews, however.

Napoleon’s institutionalised French Revolution was ultimately defeated, but only after it had swept over the whole of Europe: the Enlightenment contagion had already escaped its host and would continue to rock States as far away as Russia for decades. In Germany—a State owing its existence, physically and ideologically, to the French Revolution—where Jews were particularly concentrated, the Revolution’s approach bedded down thoroughly.14 The template repeated across the Continent. After two-thousand years of national yearning to return to a home that seemed ever-more out of reach, Jews now had a way of redefining themselves as already home: they could join the nations where they lived as full citizens who happened to privately follow the religion of “Judaism”. It would afford Jews effectively the same (increasingly-secure) status as Christian minority sects—and what could be more logical? Citizenship on these terms meant Jews accepting requirements that made them “just that bit more Christian”.15 It was a path many Jews found attractive.

The Jewish integrationist current also provoked a reaction. As a contingent matter, the “Zionist” movement or “Jewish nationalism” emerged in the late nineteenth century under the leadership largely of Yiddish-speaking Eastern European Jews—some still in the East, some who moved West—and this marked the terms in which Zionist activists spoke, with the same romanticism, populism, and socialism as other East European nationalisms in the period.16 At a deeper level, what was playing out was an internal factional struggle for the identity and future of Jews in Europe, with “Zionists” arguing for a return to Ioudaismos, for Jewish peoplehood oriented to the Land of Israel, and their opponents wanting to stay the course with “Judaism”, to continue trying to integrate into the countries of Christendom.

Theodor Herzl, the father of modern “Zionism”, having experienced the intense antisemitism in Vienna and saw the illusions of French toleration for its tiny Jewish population evaporate in the Dreyfus Affair,17 concluded that Jewish integration was a fantasy: there would never be safety for Jews as a minority; security required a Jewish State.18 The wave of pogroms in Russia in 1881 and the even worse repetition in 1905—with the blood libel-driven, Easter Day 1903 pogrom in Kishinev in between (just before Herzl died)—convinced many Jews that Herzl was correct.19 The horrific massacres of Jews during the Russian Civil War triggered by the Bolshevik coup strengthened the “Zionist” trend still further, and in the wake of the Nazi Holocaust, where patriotic Jews across the whole of Europe had been rounded up with the enthusiastic support of gentile neighbours and exterminated—where not even a conversion away from “Judaism” several generations before saved people—there was little left to say.

The final step that closed the argument in favour of Ioudaismos was the refoundation of Israel itself. The pre-1948 intra-Jewish argument over “Zionism”—whether to recreate the Jewish State—was settled once there was one. Zion became once again a pillar of Jewish life. Whether the question is framed as support for Israel generically or the deeper question of Israel as an intrinsic part of Jewish identity, something around 95% of diaspora Jews are “Zionists”. This is hardly surprising. Unlike the pre-1948 abstract positioning about a future possibility, to be an “anti-Zionist” after 1948 is to support the physical elimination of the Jewish State. That inherently murderous position is extreme for anyone to hold, let alone people tied to the State by ancient heritage and often personal relatives. So it proves on examination. The extant “anti-Zionist” Jews fall into two broad categories of fringe extremists: messianic sects like the Neturei Karta, acting on esoteric interpretations of the Jewish creed, and the secular far-Left, whose ideological premises originate outside the Jewish world.

THE BRITISH MANDATE FOR PALESTINE

The first recorded major clash between the “Zionist” enterprise and the Arabs in the Holy Land was on 29 March 1886. A dispute arose after Arabs from the village of Yahudiya stole a horse from a Jew living in the settlement of Petach Tikva, just north of what is now Ben Gurion Airport.20 The next day, a fifty-man Arab mob attacked the Jews, wounding four and causing the death of one. In 1899, two years after Herzl convened the First Zionist Congress, a group of officials from the Ottoman Empire that ruled in Jerusalem circulated a petition calling for the expulsion of Jews who had arrived after 1891.21 In 1908, in Jaffa, after an episode of the by-then endemic anti-Jewish violence in which Arabs attacked a Jewish couple on the beach, Jews fought back, and a larger Arab attack was subsequently launched that wounded thirteen. Jews considered it a pogrom. To protect the settlements, the Jews founded the Hashomer (Watchmen) in April 1909. The courage of these village guards, who were regularly killed over the next five years, made them a symbol of the “Zionist” movement.22

The Palestinian Arab attacks on the Palestinian Jews, framed as an Islamic duty, escalated and spread: as early as 1911, Jewish leaders worried whether the Hashomer was sustainable against the onslaught and by 1913 the situation was truly alarming. The most high-profile episode was the 22 November 1913 murder of an 18-year-old Jew, Moshe Barsky,23 in Degania Alef on the banks of the Sea of Galilee.24 The violence was so extensive, it drew the attention of foreigners. “The assaults upon Jews in the outlying districts are increasingly frequent”, the British Consul in Jerusalem reported in April 1914.

The First World War broke out four months later and, to Britain’s great regret, the Ottoman Empire, which had been seized by the nationalist Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), joined the German-led axis in November 1914.25 Already in December 1914, the Ottoman regional governor Djemal Pasha had begun trying to deport Jews in Tel Aviv who had been born abroad, had foreign citizenship, or were suspected of political opposition to the Empire. Though the program was slowed by international pressure, over-10,000 (about 15%) of the Jews in the area had been expelled by the end of 1915. In the meantime, the British attempt to swiftly knock the Ottomans out of the war at Gallipoli had disastrously failed. By 1917, however, the tide had turned in the Middle East.

In March 1917, on the eve of Passover, as the British (mostly in the form of the Indian Expeditionary Force) captured Baghdad and closed in on the Holy Land, Djemal ordered the expulsion of the 8,000 Jews in Tel Aviv and Jaffa, believing (correctly) that the Jews preferred British to Turkish rule. Jewish homes and other property was stolen, and handed over to Muslims. The deportation itself, and the complete lack of planning for the welfare of the deportees in the desert areas like Galilea where they arrived, killed 1,500 Jews. What happened to the Jews in Tel Aviv and Jaffa was, in miniature, a repetition of the broader policy already underway to nominally deport the Armenians and other Christians from militarily sensitive areas (basically the whole of Anatolia) to the Syrian and Iraqi deserts, a process of “death marches” and crowding the refugees into unsanitary and un-provisioned camps, which can only be assessed as intended to bring about their destruction. Had the CUP regime retained control of the Holy Land, it is likely the rest of the Jews in the area would have suffered the same fate.26

The stubborn resistance of Ottoman troops in the Holy Land from April to October 1917 was broken by a change in British tactics.27 On 11 December 1917, General Edmund Allenby arrived in Jerusalem, dismounted his horse as a sign of respect, and entered on foot, restoring Christian control over the city for the first time in seven-hundred years. In September 1918, the British offensive in the Middle East culminated at the Battle of Megiddo (or Armageddon) in the north of what would become the Palestine Mandate.28

British policy at the outset of the Great War had been favourable to continuing the policy of the prior century that propped up the Ottoman Empire. This had changed by 1916, with an Anglo-French agreement to partition the Ottoman realm after defeat.29 It was within that context that British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour wrote to Lord Rothschild on 2 November 1917, five days before the Bolshevik coup:

His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

This “Balfour Declaration”, made public a week later, was seen by Zionist activists as a great victory. Zionist lobbying, vigorous as it had been, was not the decisive factor, however. Advocates were “preaching to the converted”, writes Morris: most of the British Cabinet supported the recreation of a Jewish homeland “for Protestant religious and humanitarian reasons”, and for Imperial and strategic reasons. There were also “specific extenuating circumstances”, Morris explains:

[T]he Arabs of Palestine, like the majority of those outside Palestine, had supported and were still supporting the (Muslim) Ottoman Empire in its war against the (Christian) Allied powers; and there was, at the time, no Palestinian Arab national movement nor any separate Palestinian Arab national consciousness. Indeed, “Arab” national awareness, with concomitant political aspirations, was barely in its infancy among the elites in the neighboring Arab centers of Beirut, Damascus, and Baghdad.

Even thirty years later, there was no serious proposal by the invading Arab States to create a Palestinian government, nor was there any significant body of opinion among the Arabs in the Holy Land that demanded one. There were changes in Arab opinion in the interwar years, and some of them provided ideological guideposts for the Arab Palestinian identity, but that identity’s formation was still in the future in the late 1940s.

Prior to the First World War, so senior an Arab official in the Holy Land as the Mayor of Jerusalem, an intellectual named Yusuf al-Khalidi, had no compunction in saying, “Who can challenge the rights of the Jews in Palestine? Good Lord, historically it is really your country.” Note that this was said to a Jewish interlocuter, not behind closed doors.30 No Palestine Arab spoke like Al-Khalidi in the 1940s, certainly not publicly, because the demand to prevent Jews returning to Zion had become central and the demand was legitimated ideologically by denying there was any Jewish connection to Palestine.31

It was exclusively within the context of fighting Jewish immigration—and the British rule that was seen as enabling it—that in the 1920s a very small intellectual circle of Arabs in Palestine, journalists and politicians, began referring to a “Palestinian National Movement” and sometimes a “Palestinian nation”.32 For Arabs in Palestine in the 1940s, their primary identity was as Muslims. Islam, indeed, was the only shared loyalty among the Arab actors involved in the 1947-49 war. The Arab identity in Palestine in the 1940s was more nebulous and where it mattered it was generally more a source of division than unity, since it was felt most concretely as a loyalty to clans, tribes, and/or families that competed against one-another. Those Arabs in Palestine at the time of Israel’s rebirth who felt an Arab identity with a political valence that went beyond immediate kinship tended to conceive of themselves as Syrian, an inheritance from the Imperial administration of the Ottomans.33

When the Palestinian nationalist identity emerged as an important factor after the 1967 Six-Day War, embodied in the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), it did so defined by its opposition to Israel. It is a supreme irony that Britain and “Zionism” between them created two nations from the three peripheral Ottoman districts cobbled together into a colony after the Great War.34 This can be seen in the PLO’s definition in its 1964 Charter of what it is fighting for: “Palestine with the boundaries it had during the British Mandate is an indivisible territorial unit.” Surprising as it might seem that this most revolutionary “anti-imperialist” organisation regards the terms of a secret imperialist deal done during the First World War as inviolable, the PLO really had no other choice: the British Mandate is the first time “Palestine” appears in history as a political entity. And even this requires a caveat.

The British zone in the southern Levant had included both banks of the River Jordan, but before the British officially took over the administration of the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine in September 1923, eighty percent of the territory had been detached and given to the Arabs in an autonomous polity that would ultimately become the Kingdom of Jordan under Abdullah I, the son of Husayn bin Ali, the Sharif of Mecca who had led the British-aligned Arab Revolt during the First World War.35 Thus, “Palestine”, already carved arbitrarily by the British out of the Ottoman administrative system, was further arbitrarily redefined by London to meet obligations Britain had hastily made during the Great War and struggled to meet afterwards.

The decision on the Palestine Mandate’s borders is important for another reason: it marks the start of a British tilt towards the Arabs—and a retreat from the implications of the Balfour Declaration—that would be total by 1939, not that the non-Jews in the region seemed to notice.36 As Morris notes, “no matter what the British did …, the Arab world was to regard London as the protector and facilitator of Zionism”, and still does.37

BRITISH WITHDRAWAL AND PARTITION

The British Empire, exhausted by the Second World War, was resolved by early 1946 to relieve itself of responsibility for Mandatory Palestine, but continued to try to shape the outcome in the Arabs’ favour, driven inter alia by the perennial concern of the Foreign Office for good relations with the Arab States and concerns about creating difficulties when evacuating British troops through Arab-populated territory. Morris explains the extent of this. The British proposed handing over to an “International Trusteeship” that would give way to a single Arab-majority State, and very pro-actively tried to inhibit the transfer of Jewish survivors of the Holocaust to Mandate Palestine, detaining 12,000 Jews on Cyprus and unleashing SIS/MI6 to sabotage ships organised by the Yishuv, the proto-government the Jews had formed in the Holy Land, to bring Jewish refugees in from Europe.

In February 1947, with a Jewish rebellion ablaze in the Land of Israel for the first time in more than 1,300 years, the British threw the issue to the United Nations. 100,000 British troops were in Palestine, but the Labour government in London wanted out more than it wanted to pacify the area, and in any case the British were politically hamstrung in the counter-terrorism methods they could employ in the shadow of the Holocaust and under intense international, particularly American, scrutiny. The United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) report in early September 1947 unanimously recommended partition—two sovereign States, one Arab, one Jewish—and a termination of the British Mandate as quickly as possible.

On 29 November 1947, the U.N. General Assembly adopted Resolution 181 by a vote of 33-13, with ten abstentions (one of them Britain), for the partition plan. The Jews rejoiced; they were prepared to accept a State “even if it’s the size of a tablecloth”, as Chaim Weizmann, the first President of Israel, put it. The Arabs, by contrast, stormed out of the meeting, and prepared for war. The next day, Arabs attacked two buses near Fajja, north of Jaffa, murdering seven Jews: civil war was underway in Palestine. Riots swept the Arab world, damaging Western diplomatic facilities, and on 2 December, the ulema of Al-Azhar in Egypt, one of the premier Islamic institutions, proclaimed a “worldwide jihad in defence of Arab Palestine”. Within hours, a pogrom had erupted in Aden: the lacklustre British response to Muslim attacks on Jews in Yemen was a prefiguring of what was to come in Mandate Palestine. Simultaneously, an Arab League spokesman in Cairo “said that no Arab State recognised any part of Palestine as a non-Arab area”. Arab governments were locked into a path that led to war.

The British favour for the Arabs continued right down to the end. In June 1947, British troops began drawing down from Palestine; there were 55,000 left by December 1947. At that point, the British decided on a full-fledged scuttle: the British would leave by 15 May 1948, rather than 1 August, as the UNSCOP plan called for. This scandalous abdication of Imperial responsibility was worse than it looked. Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin regarded it as “immoral” to compel any compromise from the Arabs and refused any action that would do so. In late 1947, Britain went further, covertly agreeing to do all in its power to delay the arrival of the U.N. Implementation Commission—in other words, to buy the Arabs as much time as possible to overturn the partition plan through war, knowing full-well what that would mean for the Jews in the area.38 This was a direct revocation of the Balfour Declaration that had de facto been repudiated more than a decade earlier.

In March 1948, Muhammad Amin al-Husayni, the Mufti of Jerusalem and official leader of the Arabs in Palestine at the head of the Arab Higher Committee (AHC), the man who had been so crucial to the Nazis’ influence in Islamdom—not only in the Arab world: he helped organise Muslim SS killer brigades in Bosnia—made a public statement from Egypt, where he was camped out beyond the reach of international war crimes prosecutors, letting it be known that in the coming war the Arabs would fight “until the Zionists were annihilated and the whole of Palestine became a purely Arab State”.39

A month later, a private cable to the headquarters of the Arab Liberation Army (ALA),40 the Arab League “volunteer” army was set up in opposition to Al-Husayni’s AHC forces that was already involved in Mandate Palestine, claimed: “Morale is very strong, the youngsters are enthusiastic, we will slaughter them [the Jews]”. The ALA was led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji, a Syrian-born Nazi collaborator—he was a colonel in the Wehrmacht—who spent most of the war working for the German Propaganda Ministry in Berlin. The Muslim Brotherhood militias that had infiltrated southern Palestine under Cairo’s watch spoke in similar terms to the ALA.

While official Arab government spokesmen made some effort in public to present the war aims to Westerners in terms of “saving” Palestine or the Arabs thereof, even that was far from uniform. For example, Abdul Rahman Azzam, the Arab League’s first secretary-general, speaking in October 1947, six weeks before the U.N. partition plan was passed, made crystal clear the intentions of the Arab armies that were preparing for war to prevent the restoration of Jewish sovereignty:

This will be a war of extermination and momentous massacre which will be spoken of like the Tartar [i.e., Mongol] massacre or the Crusader wars. … This war will be distinguished by … faith, as each fighter deems his death on behalf of Palestine as the shortest road to paradise, … [and the war] will be an opportunity for vast plunder.

Immediately after the partition plan passed, Azzam said:

Centuries ago, the Crusaders established themselves in our midst, against our will, and in 200 years we ejected them. … Up to the very last moment, and beyond, they [the Arabs] will fight to prevent you [the Jews] from establishing your State. In no circumstances will they agree to it.

In the same period, Saudi King Abdulaziz (Ibn Saud) wrote to President Harry Truman:

The Arabs have definitely decided to oppose [the] establishment of a Jewish State in any part of the Arab world. The dispute between the Arab and Jew will be violent and long-lasting. … Even if it is supposed that the Jews will succeed in gaining support for the establishment of a small State by their oppressive and tyrannous means and their money, such a State must perish in a short time. The Arab will isolate such a State from the world and will lay siege to it until it dies by famine. … Its end will be the same as that of [the] Crusader States.

The theme of Israel as a new version of the Crusader States—an ephemeral, supposedly alien implant in the region that would eventually be destroyed—recurs down to the present day, at elite and popular levels in the Arab world. Yasser Arafat, the longtime PLO leader, frequently compared Israel to the Crusader States and compared himself to Saladin, the Muslim leader whose jihad shattered the Christian hold on Jerusalem in 1187. Arafat kept up these allusions even when he was theoretically negotiating to create an Arab Palestinian State to live alongside the Jewish State.

On the eve of the pan-Arab invasion in May 1948, Azzam told Alec Kirkbride, formally the British ambassador in Jordan whose role was something like the regional voice of Britain, “It does not matter how many [Jews] there are [in Palestine]. We will sweep them into the sea.” Syrian president Shukri al-Quwatli, who had earlier echoed the Crusader line (“Overcoming the Crusaders took a long time, but the result was victory. There is no doubt that history is repeating itself.”) announced the onset of the invasion to his people with a nod towards the idea the Arabs were there to “protect our brothers”, before concluding, “We shall eradicate Zionism”.

THE INTERNAL WAR FOR PALESTINE

On the ground in Palestine after November 1947, British troops were theoretically neutral: they were to protect themselves and try to keep the two sides apart. This neutrality was upheld in its way by the British ceding installations to whichever force captured an area—the Arabs in Judea, Samaria, and Galilee, and the Jewish Haganah on the Coastal Plain and the Jordan and Jezreel Valleys—and up to March 1948 the Jews’ gained some advantages from the limited British peacekeeping interventions, since the Arabs within Palestine were on the offensive and the Haganah was still being reorganised and equipped, and the British presence prevented invasion from the Arabs outside Palestine at a time when Jewish forces were dealing with this internal onslaught.

Overall, though, the British tilt was overwhelmingly in the Arabs’ favour. The British were stringent in enforcing the blockade on Jewish support from abroad to the Haganah, while being much less strict about Arab aid flowing over the borders; the Haganah was prevented from any large-scale operations; the only major British interventions to suppress and disarm militants were directed against Jews, with these confiscated weapons not-infrequently handed over to the Arabs; and there were a series of awful incidents where British troops “released” disarmed Haganah operatives to Arab mobs, who lynched them and mutilated their bodies. On occasion, British troops even provided covering fire for Arab attacks.

The British thumb on the scales could not overcome the fundamentals in Mandate Palestine, though. As noted by Morris, on paper, the Arabs had it all their own way: 1.2 million Arabs, located over a far greater surface area and occupying the high ground, were facing 630,000 Jews.41 Add in the British pro-Arab tilt and the support from the Arab hinterland, and this was a desperately unequal struggle the Jews could not win.42 True, the Jews had taken some steps to mitigate this, above all by ensuring the battle-hardened survivors of the Anti-Nazi War made it to Palestine first. But it was in the intangibles that the differences really mattered:

Facing off in 1947-1948 were two very different societies: one highly motivated, literate, organized, semi-industrial; the other backward, largely illiterate, disorganized, agricultural. For the average Palestinian Arab man, a villager, political independence and nationhood were vague abstractions: his affinities and loyalties lay with his family, clan, and village, and, occasionally, region. Moreover, … Palestinian Arab society was deeply divided along social and religious lines.

The defeat of the Arabs within Palestine in 1947-48 was the price paid for the 1936-39 Arab Revolt. The Revolt had appeared successful, generating the May 1939 White Paper, which made Britain’s hostile view of “Zionism” into official policy for the remainder of the Mandate. All of the Arabs’ key aims were granted: there was a radical restriction of immigration by Jews fleeing Hitler in Europe, a prohibition on Jews buying land, and the 1937 Peel Commission’s partition recommendation was abandoned.43

Beneath the surface, however, the Revolt had been a catastrophe for the Arabs. As a military campaign, it was hopeless against British troops, killing off thousands of Arab militants, and it left the Arab economy in ruins from which it, unlike the Yishuv, never recovered. Politically it was even worse. The 1930s uprising petered out in a sorry bloodletting among Arabs—just as happened half-a-century later at the end of the First Intifada (the so-called “intrafada”). Many leaders of the Palestine Arabs left and never came back. The society left behind was torn apart, Morris documents, riven, especially among its “more literate and politically conscious” sectors, by “a deep, basic fissure”, between the Husaynis and Nashashibis.

Instead of building the AHC into a proto-government—even a despotic one—capable either of accepting responsibility for an independent State awarded by partition or waging the war for the whole Mandate that Amin al-Husayni so often boasted was coming, Al-Husayni’s allies spent the decade after the Revolt witch-hunting the Nashashibi faction, preventing it acquiring positions on the AHC and the access to land, personal wealth, and power, which were the main preoccupations of the Husaynis. The Mufti’s attempt to lead the AHC from exile, with his deputy, Jamal al-Husayni, in Mandate Palestine, was a shambles. Most elite Muslim families fell afoul of the Husaynis and refused to fight for the AHC. The “Husayni terror” against Arab Christians collapsed military units in places like Nazareth. AHC “departments” and command-and-control infrastructure were non-existent. The lack of a unified vision—beyond Islam—meant the Yishuv was able buy land, and recruit spies, from every Arab faction and tribe. Above it all, there was the psychological factor of the Arabs in Palestine not believing they had to work for their own salvation; they were relying on the Arab States rescuing them.

The contrast with the Jews could not have been more stark. Two years after the crematoria at Auschwitz had gone cold, there was no illusion that anybody was coming to save the Jews. That what had started in Europe would be completed in Palestine if the Yishuv went under was self-evident to everybody. Motivation and morale were sky-high among the Yishuv Jews, “one of the most politically conscious, committed, and organized communities in the world” at the time, as Morris notes. The Jewish Agency for Palestine, the official name of the Jewish proto-government, was staffed by educated and competent men and women, chosen on merit, who had organised a State-within-a-State that could carry out everything from foreign relations to an autonomous school system. This idealism proved infectious.

The Arab side attracted a trickle of foreign volunteers motivated by antagonism to the Jewish project, namely, some former British soldiers angered by their experience with Jewish terrorism, and the remnants of the Third Reich: some Nazi intelligence and Wehrmacht officers, as well as a few dozen Balkan Muslim veterans of the SS Handschar Division. On the other side, humanitarian and ideological motives led about 4,000 volunteers, Jewish and non-Jewish (Christians and socialists), to join the Haganah from all over the world, among them pilots, communications experts, and sailors—all badly needed by the Jewish army.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the Jews in Mandate Palestine had been hesitant to take up arms, since its socialist leaders conceived of their project to restore Zion as one that could be done via an accommodation with the Arabs and an “overreaction” to Arab provocations would make it difficult for “moderates” to come to terms with them. This mindset inspired Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the godfather of “Revisionist Zionism” who had done battle in Palestine during the Great War, to pen his famous “Iron Wall” essay in 1923, expressing acid contempt for such naiveté. By 1947, after all the anti-Jewish violence of the pre-First World War period, the pogromist outrages around Passover 1920, the “riot” in Jaffa in May 1921, the August 1929 massacre of sixty-plus Jews in Hebron, and the 1930s Revolt, the point had been taken. The Jews gave negotiation one last chance with the partition plan, and once the Arabs rejected it went to war.

There would be no guesswork this time, no waiting to see if some moderate on the other side came to their senses to offer an amicable settlement. “Plan D” was formulated: decisive, effective force would be employed to lock down Jewish population centres, ensure the safety of the major roads linking them, limit Arab ability to wage guerrilla war behind the lines, and seal off invasion routes, securing the borders of the Yishuv specified in the U.N. partition plan. The Jews had been given a promissory note and they were determined to collect on it.

No war goes entirely to plan. Plan D was to go into effect in early May. Until then, the Haganah strategy was to contain the harassing Arab terrorist attacks and deter escalation with targeted retaliation. This brought some success in tying down Arab forces in defensive operations and undermining public confidence that the AHC could protect its own people. The primary indicator of the weakness of morale was that maybe 100,000 mostly middle class Arabs fled in this phase, many within Palestine and some abroad, with the knock-on effect of a disruption of Arab economic activity. But a dangerous series of military setbacks for the Yishuv in March 1948 led to the Americans wavering over the partition plan.

The U.S. State Department, in particular its Policy Planning Staff, had opposed the emergence of a Jewish State from the beginning, for a mixture of strategic and sentimental reasons (an institutional antisemitism, to be blunt about it), and with the turmoil in Mandate Palestine they had a chance for one last run at winning over President Truman. The British “Trusteeship Scheme” was revived: the partition plan would be abrogated and eventually a single Arab-majority State would be created. The U.S. Ambassador to the U.N., Warren Austin, made a forthright public statement to this effect in mid-March 1948. The State Department presented its plan to sabotage Israel—this should sound familiar—as necessary for “peace” and its primary mechanism would be a ceasefire. As it turned out, Austin had been speaking in direct defiance of the President’s wishes, and Truman was able to rein-in the bureaucracy.

It took some time for the Yishuv to get clarification on the American position, however, and Austin’s statement caused real alarm, especially in combination with the military reverses around Jerusalem. A change of Yishuv strategy was needed. Having used the time to recruit and reorganise the Haganah, with arms from the Soviets delivered through Czechoslovakia beginning to arrive, gambling that the British force (down to 25,000) was so depleted it would not intervene, and working with an ineluctable timetable for the arrival of the Arab armies, the Yishuv went on the offensive on 1 April 1948.

A week into the Haganah offensive, two events took place that essentially broke Arab morale.

Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni, a Jerusalemite Arab who had been expelled from Mandate Palestine in 1939 after the Revolt and gone to Iraq to help set up the pro-Nazi government of Rashid Ali al-Gaylani, was a rare elite returnee to Palestine, in January 1948. Abd al-Qadir led the Sacred Jihad Army (SJA), nominally within the Mufti’s AHC, and became the most visible Arab military commander of the civil war phase.44 The SJA, however, was merely one of a multitude of Arab forces alongside Al-Qawuqji’s ALA, local militias in the towns and villages, the Muslim Brotherhood, and a Bedouin contingent. None coordinated with each other, nor with the Arab League Military Committee in Damascus that was theoretically managing the Arab war. Some factions answered to specific Arab governments, and they all often competed more against each other than against either the Jews or the British. The Mufti’s trip to Syria to sort the mess out on 5 February 1948 created a rough division of theatres of operation, but whatever traces there were of an Arab command-and-control structure died with Abd al-Qadir on 8 April.

There had been a potential SJA successor, Hassan Salameh, another Palestine-born Arab who had followed the Mufti into the 1930s Revolt, the service of Rashid Ali, and then to Berlin. Salameh had become a Wehrmacht officer and was parachuted back into Mandate Palestine by the Nazis in October 1944 as part of a detachment of Germans and Arabs ordered to carry out terrorism against Jews. The operation failed, but Salameh was able to use the Nazi weapons caches buried in Egypt for a rebellion-cum-pogrom Abd al-Qadir never got to initiate and dozens of Jugoslav Muslim SS veterans to wage war on the Jews in late 1947. Unfortunately for Salameh, his other lasting Nazi asset, a German officer who served as his chief adviser, was eliminated by the Haganah in a bombing of the SJA headquarters near Ramla on the night of 4-5 April. Arabs fled from the surrounding villages and this was a “mortal blow” to Salameh’s reputation, Morris writes. With confidence in Salameh shot, Arab society was more than ever reliant for its morale on Abd al-Qadir—and then he was killed three days later.

The shockwaves through Arab society in Mandate Palestine after Abd al-Qadir’s death were compounded a day later when Deir Yassin, a key village west of Jerusalem, fell to Jewish troops, specifically the Irgun and Lehi, which were coordinating with the Haganah but not yet under its command. These two groups, responsible for the terrorist campaign against the British after 1944, carried out atrocities during and after the capture of the village. The Arab media lit up with vastly exaggerated claims of casualties—about 100 people were killed in total, combatants and civilians—and terrifying details were invented. Outside Palestine, this had the desired effect of inflaming public opinion sufficiently to prevent Arab leaders backing out of the invasion once the British were gone. Within Palestine, however, the effect was precisely reversed: to an Arab population already despairing after the loss of its charismatic commander, already wary of living under Jewish rule—the more so because Al-Husayni’s people tended to designate those who remained in Haganah-occupied areas as “traitors”—the idea the Jews were no longer playing by the rules triggered further panic flights.

The slaughter of eighty Jewish academics and doctors on Mount Scopus, most of them burned alive, on 13 April, gave the Arabs revenge for Deir Yassin, and fortified Jewish resolve even further. Plan D called for Arab villages adjacent to the roads or Jewish cities to be occupied and destroyed if they resisted in order to remove the Arab population and ensure it could not return: the willingness to take chances on this front considerably diminished.

When the fighting was highly localised, disorganised, and small-scale up to March 1948, the Arabs could hold their own. The Arabs could not hold off against large-scale, coordinated, and sustained force over a wide area. The Haganah offensive quickly shattered the Arab militias and with their demise Arab society in Palestine cracked.

THE NATURE OF THE ARAB WAR

Some revisionists have argued that it was impossible for the pan-Arab coalition to destroy Israel in 1948, and that this was never the Arab intent. The first is more true than the latter, though neither was clear at the time. What is true is that when one zooms in, there is something darkly funny about the high politics among the Arab coalition.

Jordan’s King Abdullah had secretly reached terms with the Yishuv—Golda Meir was the emissary—on 17 November 1947: Israel would be created and Jordan would annex the core Arab areas around Ramallah, Nablus, and Hebron (“the West Bank”), an arrangement green lit in understated British fashion from London in February 1948. Abdullah wanted all of Mandatory Palestine and the Jews to accept an autonomous “republic” under his sovereignty. Failing that, the King preferred the Jews as neighbours to an Arab State run by Amin al-Husayni. Whatever misgivings the Jews had about the Hashemite monarch, they shared his view of the Mufti. This arrangement broke down on 10 May 1948 because Abdullah was hemmed in by having to fight in coalition, the frenzy the Arab leaders had worked themselves into, and some genuine angst over Deir Yassin. This is why the Yishuv leaders did not know what to expect from Jordan on 15 May. In fact, Abdullah basically stuck to the deal—and announced to the Arabs his goal was the West Bank on 14 May. The withdrawal of Jordan’s Arab Legion—the best Arab army, led by British officer Sir John Glubb—from the eliminationist mission almost certainly doomed it, and it had further consequences.

Egypt’s King Faruq—part of the anti-Hashemite bloc with Saudi Arabia and Syria—had been extremely reluctant to go to war. Egypt was not even part of the Arab coalition when the final decision for an invasion was taken on 30 April. At the secret debate in the Egyptian senate on 11 May, Ahmed Sidqi Pasha, a former prime minister, was treated as a leper and left after asking, “Is the army ready?” They all knew the answer was “no”. The vote for war was unanimous anyway. With Abdullah’s announced war aims on 14 May, Faruq now had preventing Jordan taking all of the West Bank as a priority on par with uprooting the Zionist project, which he deeply and sincerely hated.

Hashemite Iraq had been—along with Syria—the most heated in its pre-war rhetoric, threatening even in private several times to intervene before the British had departed. Yet, the Iraqis knew their weakness and they were bound to Jordan, so in principle Baghdad’s goals were now circumscribed and its abilities were even less than that.

Meanwhile, Christian-led Lebanon, always determined to prove it was as Arab as the rest, had pressed Egypt to get involved, only to suddenly announce—hours after Abdullah’s unilateral change of war aims—that it was effectively staying out. This was partly because last-minute Yishuv actions on the northern border had locked down the invasion route. This was more due to psychological warfare than actual military operations: a “whispering” through Arab agents of the Yishuv that it was best if the Arabs got out of the Jews’ way led to an exodus. This was in an atmosphere of sheer hysteria; rumours days earlier said the Jews were using “atom” bombs, which some thought explained the unusually heavy rain. In the end, only a token force of several hundred Lebanese soldiers crossed into Israel.

The combination of Jordan’s and Lebanon’s about-face forced Syria to shift “their point of invasion from Bint Jbail to the southern tip of the Sea of Galilee”, Morris explains, which meant that the day before the invasion the Syrian army spend its time “driving from southern Lebanon to the southwestern edge of Syria, opposite al-Hama”.

Kirkbride, the British man on the scene, was flabbergasted watching the Arab war preparations.45 The problem for Arab rulers by May 1948 was that they were trapped by their own consistently bellicose rhetoric, which had stoked a febrile atmosphere that gave them no room to move against pressure for war from below, from the “street” and the politically conscious middle-class, and from other Arab leaders, who prodded each other inexorably forward, each hoping the others had strength enough to mask their own weakness. This was a mirage, of course: the Arab armies, then as now, are designed more for domestic repression than foreign war-fighting.46 What none of them could do was step back from the brink: it was more physically dangerous for the Arab rulers in 1948 to refuse to enter the war against the Jewish State than it was to take the plunge on a war many of them knew they would lose.

This is all clear only in retrospect. “The Yishuv was genuinely fearful of the outcome—and the Haganah chiefs’ assessment on 12 May of a ‘fifty-fifty’ chance of victory or survival was sincere and typical”, writes Morris. “The Zionist leaders deeply, genuinely, feared a Middle Eastern reenactment of the Holocaust, which had just ended”. Nor was this unreasonable. The Arab leaders’ publicly-expressed desires were quite sincere: “The Arab war aim, in both stages of the hostilities, was, at a minimum, to abort the emergence of a Jewish state or to destroy it at inception.” Limited Arab capacity prevented the realisation of this dream, and Jordan’s King was pragmatic enough to work within this reality. All the same, had Israel’s defences failed in 1948, there is no doubt there would have been a genocidal slaughter of Jews. In the areas that were overrun by Arab troops and irregulars, there was a “systematic destruction of all the Jewish settlements”, Morris notes.

Morris ends the book on this point, criticising historians who downplay the religious motivation on the Arab side. The contemporaneous evidence—quoted in spades by Morris throughout the book—is overwhelming.47 The war against Israel was ubiquitously framed as a jihad, the fate of the Crusader States was often mentioned, and the idea was regularly propounded that “martyrdom” in the struggle was “the shortest road to heaven”, as King Faruq put it.

When it came down to it, the Arab war was not about the land and it definitely was not about the Arabs in Palestine per se. It was a fundamental rejection of the idea that infidels should have sovereignty in territory that had been under Islamic rule. The Arab League secretary-general Azzam directly made the comparison to Spain, noting that Muslims “have become accustomed to not having Spain” and that perhaps “we shall become accustomed to not have a part of Palestine”, but he doubted it. As well he might. Iberia was recovered by Christendom in 1492, but the physical struggle was far from over,48 and well into the eighteenth century Muslim ambassadors in Iberia would, when mentioning their location, add, “May God soon return it to Islam”. This invocation and the worldview that goes with it applied even to far-flung places that Muslim armies held only very briefly, such as Polish fortresses in Ukraine.49

There was never a renunciation of the Muslim claim over Spain or anywhere else—how could there be, without a central Islamic authority?—and there are outlying Muslims who still make the claim. Azzam was obviously correct that for most Muslims now, the idea that Spain is theirs just has not occurred to them, though it would be interesting to see the results if opinion was tested about the Muslim “right” to Spain. The difference with Israel is not just an issue of time. Muslims always found it easier to put out of mind peripheral territories that were lost.50 Israel is too close to the heartlands of Islam and the issue is obviously sharpened by the Tradition that has grown up around Jerusalem as an Islamic sacred site, as well as the absorption and Islamization of Christian antisemitism throughout Islamdom.

ISRAEL CONFRONTS THE PAN-ARAB INVASION

The Yishuv’s leadership had some inkling of the tensions among the Arab States, but nothing concrete. To the very last, all the Jews in Mandate Palestine knew for sure was that an invasion was coming. Which States would participate and what exactly they would do was more opaque. Some in the Yishuv command were confident Jordan did not mean to conquer all of the Jewish State. There were questions about whether Egypt would participate. As against this, French intelligence told the Yishuv days before the pan-Arab invasion that Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon would invade on 15 May with the aim of occupying the whole of Mandatory Palestine “and their arrows would be directed at Tel Aviv.” Morris writes that the 1948 war was “universally viewed, from the Jewish side, as a war for survival”.

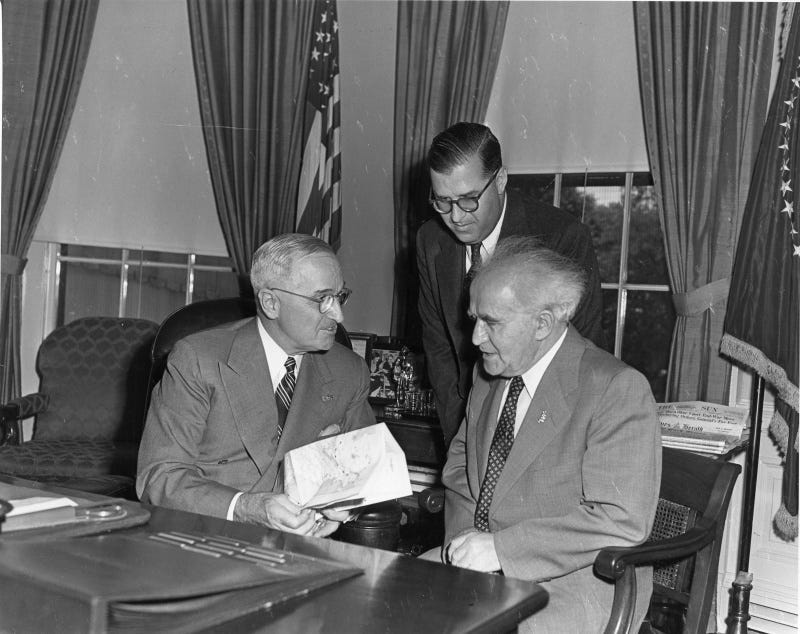

This was the backdrop on the afternoon of 14 May 1948, shortly after British High Commissioner Alan Cunningham and his staff left Jerusalem, when the Yishuv leadership gathered in a hastily arranged ceremony in a hall in Tel Aviv Museum. With the dignitaries in the hall beneath a large portrait of Herzl flanked by two soon-to-be Israeli flags, “At 4:00 PM all rose, spontaneously, and sang ‘Hatikva’,” Morris documents, and the Yishuv leader David Ben-Gurion then read out Israel’s declaration of independence, the “Scroll of the Establishment of the State of Israel”. To the State Department’s immense shock, eleven minutes later President Truman recognised the State of Israel. The Soviet Union soon followed. By midnight, the remnants of the British Mandatory authorities were aboard a Royal Navy vessel. The way was now clear for the pan-Arab invasion.

20,000 Arab troops and thousands of irregulars invaded Israel on 15 May 1948, seventy-six years ago yesterday. The Egyptians came through Gaza and attacked Jewish population up the coast towards Tel Aviv, while another column thrust across the Negev towards Jerusalem; the Jordanians made for Jerusalem; the Iraqis moved to the north around Jenin and subsequently Nablus; and the Syrians (with the one contribution of the Lebanese) came in further north again in the Galilee. As expected, the Jordanians proved to be the toughest army, and the most politically difficult to handle. The Jewish army was hesitant about major actions in Jerusalem because, said Ben-Gurion, “Jerusalem is different. It could antagonise the Christian world.” At one level, it can be said to show how much things have changed; at another, if for quite different reasons, they remain much the same.

In a pattern that certainly can be said to be constant in the war writ large, the longer the war went on, the more powerful Israel became and the more debilitated the Arabs became by their weaknesses. By June 1948, the alternate sources of arms, ammunition, and spare parts the Yishuv had organised to circumvent the international embargo were flowing into Israel, and by the war’s end domestic industrial capacity was beginning to produce their own weapons and parts. The Arabs had much larger amounts of equipment at the outset, but a lot of it was poorly used and they had to fight with the stocks they had since they had failed to prepare workaround resupply networks. The Arab air forces of Egypt, Syria, and Iraq—formidable on paper—proved useless in practice. The Israelis, with basically no air force in May 1948, had air superiority by October, with their own pilots joined by American, Commonwealth, and European veterans.

In the spy war, there was simply no comparison: the Arabs had barely any intelligence capability, and their analysis was heavily polluted by stereotypes of unmartial Jews and frank wish-thinking. Egyptian officers veered between abject panic and overconfident predictions of it taking two weeks to capture Tel Aviv. Technological competence, and proficiency with modern war tactics were also night-and-day in Israel’s favour.

The differences in organisation and morale also began to tell. In May-June 1948, the Israel Defence Forces (IDF)—as the reflagged Haganah was known—had disciplined and disbanded the remaining independent forces on their own side, the Lehi and the Irgun, absorbing those who would be absorbed across the IDF. The 65,000 IDF personnel in July 1948 became 108,000 in January 1949, thirteen percent of the Jewish population in the Holy Land. The Jews were compact, with short lines of communication, and fighting for the most emotionally intense possible causes: their homes, and their lives and those of their families.

The Arab forces also rose between July 1948 and January 1949, from about 40,000 troops to at best 60,000, augmented inter alia by 1,000 troops sent from Saudi Arabia and smaller contingents from Sudan, Yemen, and Morocco that were attached to the Egyptian army. But the Arabs were divided among themselves as to their loyalties and objectives, and dismally led, with shambolic communications and rapidly dwindling supplies. The remnants of the AHC-related irregulars faded away rapidly, and the incompetence and mendacity of the ALA leadership was staggering.

In another familiar feature of the conflict, seeing the Arabs fading in a war they had started, the United Nations began trying to secure peace through Israeli concessions. The first of the internationally-mandated truces, imposed a month into the war on 11 June 1948 (lasting until 8 July), can be said to have been even-handed, but the second truce, imposed on 18 July (holding to 15 October), and especially the third truce, imposed on 22 October (not really effective until 9 November and massively violated after 22 December until 7 January 1949), were flagrantly pro-Arab interventions. For the more reality-based Arab leaders, international intervention along these lines had been the hope.51 The Israelis, naturally, resented their successful counter-attacks being circumscribed with cramped time-limits imposed by the Great Powers, namely Britain and America, whether acting through the United Nations or individually. (When this was done through the U.N., the Soviets generally favoured Israel as a way of undermining Britain. Moscow would soon change its policy when it became clear Israel was going to be Western-oriented.)

If the U.N. intent in 1948 to restrain Israel’s defensive actions was to become familiar in the conflict, though, so was the practical effect: the truces were meant to preserve the Arab position so they could negotiate more effectively; instead, the Arabs refused to negotiate and their position deteriorated as Israel used the time better, to rest, resupply, and “cheat” more effectively, “‘steal[ing]’ extra days of fighting to achieve or partially achieve objectives”.

By the time of the second truce, in mid-July 1948, after the battles of the “Ten Days”, Israeli survival was assured. Lydda and Ramla, the “two thorns”, as Ben-Gurion called them, threatening the old main road and Tel Aviv, had been cleared, and the torrential refugee flow onto the West Bank had both politically destabilised Jordan and severely undermined Britain’s position among the Arabs. “Glubb Pasha” was accused on the “street”, and by Arab governments envious of Jordan’s relative success, of working for the Jews. In the first week of August 1948, the IDF shifted its focus from defence to offense, intending the complete eviction of the Arab armies from all of Mandatory Palestine.

Responding to escalating Egyptian attacks, Israel launched Operation YOAV on 15 October. Soon hemmed in again by a U.N. Security Council truce set for 22 October, the IDF had to choose between cutting Egyptian lines of communication around Beersheba in the Negev or pushing down the coast from Tel Aviv; they opted for the former and “stole” an extra two days. Fed up with the ALA sniping and other actions on the northern front, Israel began Operation HIRAM in the Galilee on 29 October and against the clock of another ceasefire cleaned up by 31 October, setting the de facto borders with the Syria and Lebanon. Israel “stole” another base on 9 November in Operation SHMONE, evicting the last Egyptian troops from Iraq Suwaydan, fully opening the main road to the Negev and the Ashkelon-Bayt Jibrin road, and encircling Egyptian troops in the “Fallujah pocket”. For the next six weeks, with the exception of the IDF’s Operation ASSAF (5-7 December) to disrupt the Egyptians in the western Negev, the delusive “Third Truce” was more or less observed. On 22 December, Israel launched Operation HOREV to finish with the Egypt’s brigades around the Gaza Strip and the Egyptians collapsed quickly.

Invading Arab forces were expelled from Israeli territory on 28 December 1948, and the IDF followed the disoriented Egyptians into the Sinai, provoking a most un-British rending of garments in London. Such was the atmosphere that the British were considering options for a direct military intervention against Israel. Israel shooting down five reconnaissance Spitfires and killing two British pilots over the Sinai on 7 January 1949 did not help. The expected British retaliation—airstrikes on Israeli air installations—did not arrive, but Anglo-American patience was clearly at an end. The international pressure convinced Israel’s leaders—to the absolute fury of the IDF commanders—not to annihilate the encircled Egyptian army in the Fallujah pocket or Gaza Strip, and to agree to a final ceasefire hours later on 7 January. There were some further skirmishes, but the last Israeli action of the war, Operation UVDA (5-10 March 1949) in the southern Negev, was in a zone occupied by Jordan—which had barely touched the IDF since the “Ten Days”—and in territory that had been awarded to the Jews under the U.N. partition plan; it was more a handover than a conquest.

The Egyptian entry into armistice talks had a domino effect. Embarrassing as the Arab rout was, the U.N-mediated armistice agreements completed the work of the truces by sparing the Arabs from utter humiliation and a devastatingly decisive defeat; the Arabs were not forced to recognise the ceasefire lines as Israel’s borders and the Arab States were left with footholds within former Mandate Palestine (albeit, as with nearly all the other anti-Israel international interventions, this ultimately backfired). The Israeli-Egyptian armistice was signed on 24 February 1949, Lebanon signed on 23 March, Jordan (also representing Iraq) signed on 3 April, and Syria effectively agreed to an armistice simultaneous with Jordan, though a formal Syrian signature had to wait until 20 July. A military coup had toppled the Syrian civilian government in March 1949, the first of the Arab wartime regimes to tumble. Within a few years, and the Egyptian and Iraqi monarchies were gone. Lebanon, having more-or-less stayed out of the war, and Jordan, having been “relatively victorious”, in Morris’ words, managed to preserve their governing systems, but the wartime leaders—Lebanese Prime Minister Riad al-Solh and King Abdullah—were assassinated within days of each other in July 1951. Many Arabs felt Abdullah had doomed himself by showing too much openness to peace with Israel.

When the guns fell silent, Israel had suffered nearly 6,000 fatalities (about one-quarter civilians), a full one percent of the Jewish population in the former Mandate Palestine area, and 12,000 were seriously wounded. The total Arab military casualties remains uncertain, but can be assumed to be somewhat higher. The number of Arab civilians killed in massacres amounted to 800.

A key issue still extant from 1948 is the 700,000 Arab refugees from Palestine. Morris does not shy away from myth-busting about the Israeli story of “purity of arms”. Morris insists on perspective being maintained: the 1948 war as a whole was “noteworthy for the relatively small number of civilian casualties”. But the civil war phase in particular was a nasty urban conflict and Morris documents without obfuscation or apologia what we would now call war crimes on all sides. When it comes to “transfer or expulsion”, the evidence simply does not support the claim that there was a premeditated, centralised Israeli scheme for the ethnic cleansing of Arabs, Morris explains. Transfer was “never adopted by the Zionist movement or its main political groupings as official policy at any stage of the movement’s evolution—not even in the 1948 War”.52 The acceptance of transfer in any form among the Yishuv hierarchy had been slow in coming, crystalising largely as a reaction to Arab conduct, the terrorism of 1936-37 and the wartime alliance with Hitler,53 and it was never “general”: central Galilee and “the Jewish coastal strip, Haifa and Jaffa”, retained substantial Arab populations, for example, and Israel’s population by the time of the armistices was twenty percent Arab, which obviously would not have been true if there was a master plan to expel all the Arabs from the new State.

Authority was left with local IDF commanders to use their best judgment with Arab populations that had demonstrated a threat behind the lines. While there were a handful of local cases where this resulted in deliberate expulsions, on the transfer issue the most important element was the broader policy, codified by the Israeli Cabinet in late July 1948, of preventing Arabs returning by demolishing the 350 or so villages depopulated after the Arab inhabitants were displaced during the fighting or in the panic flights. This policy was undertaken on security grounds, to avoid the dangers of a fifth column during a struggle for survival, in a war the Arabs started in both phases, and in September 1948 the Israeli Cabinet resolved to deal with the issue “as part of a general settlement when peace comes”. But peace would never come—the Arabs would only agree to armistices—relieving the Israelis of the security dilemma, and the challenge of coping with the destabilising demographic and political implications, from a refugee return.

Population displacements were common in the late 1940s. On the Subcontinent, another British territory that was partitioned in 1947 and collapsed into a war that lasted until January 1949, perhaps twenty million people were driven out or fled in either direction between India and Pakistan. Twelve million Germans were expelled from Eastern Europe as the Soviets conquered the area. Ninety million people were displaced in China. All these cases were solved because the United Nations either stayed out, or set up a specialised agency that permanently resettled people in new countries and then disbanded itself. Palestine, by far the smallest displacement of the era, was to be the sole exception.

Alone of the 1940s agencies, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) still exists and so far from working to resolve the problem, it has actively perpetuated it. UNRWA “does not have a mandate to resettle Palestine refugees”, and has extended refugee status—in defiance of the written conventions—to the descendants of Arab refugees from Palestine so that by 2024 the U.N. recognises 5.9 million people in the category “Palestinian refugee”. For the Arab States, to grant citizenship to the Palestine Arabs and let them build new lives would be an admission the verdict was in on the existence of the Jewish State. Even within Mandatory Palestine, where, for eighteen years after 1949, Egypt occupied the Gaza Strip and Jordan occupied (formally annexed) East Jerusalem and the West Bank, the displaced Arabs remained “refugees”. (There was a notable lack of Arab demand for these areas to become a Palestinian State, too.) The “right of return” for the refugees became the principal mechanism of political warfare in the struggle against Israel’s legitimacy and existence,54 and the Palestine Arabs in their “camps” (really small cities), sustained by international handouts and nurtured on antisemitic incitement under U.N. auspices,55 served in the meanwhile as a “ready pool for recruitment of guerrillas and terrorists who could continuously sting the Jewish state”, as Morris puts it.

An even more direct contrast with the fate of the Arab refugees from Palestine is what happened to the 700,000 Jews who fled or were expelled from the Arab lands between May 1948 and December 1951: all were settled in new homes in Israel, doubling the population of the new State. Efforts were made to “normalise” the issue. Israel proposed an unofficial recognition of the displaced Mizrahi Jews and Palestine Arabs as a “population exchange”, as had happened between Greece and Turkey in 1923. Israelis regarded this as generous, since the Arabs had been displaced in a war they started and the Jews had been entirely innocent. At other points, Israel offered to take in some tens of thousands of Arabs as part of a final peace settlement. Israel was to find no will on the other side for such arrangements; expulsion had been the point. The June 1941 pogrom in Iraq that slaughtered 200 Jews in reaction to the downfall of Rashid Ali’s pro-Nazi government and the murderous riots in British-ruled Libya that killed 150 Jews in November 1945—before Israel was restored, before war in Palestine, before the partition plan—were harbingers.56 While expulsionist thinking was “a minor and secondary element” among the Jewish leaders, writes Morris, “and was usually trotted out in response to expulsionist or terroristic violence by the Arabs”, on the Muslim side “expulsionist thinking and, where it became possible, behavior, characterized the mainstream”, as had been visible since the Ottoman era, where the expulsionist calls of 1899 became practice in 1914-17. Israel would go through a second round of war on the point in 1967.

Post has been updated

NOTES

Though significantly diminished after 135 AD, the Jewish presence in—the physical connection to—the Holy Land or the Land of Israel or Palestine was never broken.

The Great Sanhedrin remained operational until 358 AD, a few years after the Jews had tried yet again to recover their autonomy, rising in revolt against the Caesar in the East, Constantius Gallus (r. 351-54). The post of Jewish patriarch (nasi) was only finally swept away in 425. Another Jewish rebellion in 614-17, during the great war between Byzantium and the Sassanian Persians, brought Jerusalem briefly back under Jewish control, and Jews were still a probable majority in the Land of Israel when the area was conquered by the Arabs in the 630s.

The Crusaders in 1099 found plenty of Jews in Jerusalem, and Jews were still present, if notably reduced in number, when Benjamin of Tudela arrived in 1170. The number of Jews returning to Zion over the next half-a-millennium surged at various times—in the twelfth century as technological developments made travel easier, at the end of the fifteenth century because of the expulsions in Spain and Portugal, in the late eighteenth century and into the nineteenth century under the guidance of Vilna Gaon—but always there was a flow of Jews determined to live and die in the land of their fathers.

In 1881, the year an organised movement of Jews back to the area began, there were 20,000 Jews in the Holy Land, alongside 40,000 Christians and 400,000 Muslims. Most of this population lived north of Beersheba, about ten percent in Jerusalem.

Brent Nongbri (2013), Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept, p. 3.

The other universalist monotheism, Islam, describes itself as a dīn or deen (دين), which is often translated as “religion”, and it is easy to see why this is considered a reasonable shorthand for an English-speaking audience, even if the translator understands there is a difference. But, as the late Bernard Lewis explained, it is deeply misleading in two senses.

First, says Lewis, “religion” in the Anglosphere sense—a belief, chosen by the individual, played out in rituals that take place in designated religious settings—understates what deen refers to: “For Muslims, Islam is not merely a system of belief and worship, a compartment of life, so to speak, distinct from other compartments which are the concern of nonreligious authorities administering nonreligious laws; it is the whole of life, and its rules include civil, criminal, and even what we would call constitutional law.” Second, flowing from the first, equating deen with “religion” in a Christian sense creates a parallel between “the mosque” and the Church that does not exist—to that extent, it overstates what deen refers to. The mosque is “a building” and “a place of worship”, Lewis points out, but not “an institution”: “There could be neither conflict nor cooperation, neither separation nor association between church and state, since the governing institution of Islam combined both functions.” The roles of Pope and Emperor were fused in the Caliph.

The connotations Muslims attach to deen, and the history this perception has produced, are not accidental; it is written into the etymology. The cognates of deen in other Semitic languages, notably Hebrew (דין), mean “law”, or “judgment” in the sense of a ruling by strictly interpreting the law—hence the rabbinical courts being called Beth Din (the House of Judgment). What deen signifies is not private belief, but public practice and custom, down to such minutiae as dress and diet, and the ordering of what Christian cultures would consider the “legal” and “political” realms—the whole scope of society and State. As such, deen is better translated as “lifeway” or “way of life”. Another possible translation is “creed”, though it has a more exact Arabic counterpart in “aqeeda”.

Tom Holland (2019), Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind, pp. 483-484.

Mary Beard, John North, and Simon Price (1998), Religions of Rome: Volume One: A History, pp. 22-26.

Paula Fredriksen, an American historian of early Christianity, has put it this way: “Jews may be one of the few groups now for whom ethnicity and religion closely coincide, [but in antiquity] it was the least odd thing about them.” Quoted in: Daniel Boyarin (2018), Judaism: The Genealogy of a Modern Notion, p. 36.

Boyarin, Judaism, pp. 38-48.

Before Religion, pp. 53-55.

Before Religion, pp. 65-66, 110-12.

Dominion, pp. 475-76.

As Indian historian S.N. Balagangadhara has put it, “Christianity spreads in two ways: through conversion and through secularisation.” Quoted in: Dominion, p. 475.

Marion A. Kaplan [ed.] (2005), Jewish Daily Life in Germany, 1618-1945, p. 331.

Dominion, pp. 481-82.

Dominion, pp. 478-80.

Dominion, 482.

Bernard Lewis (1986), Semites and Anti-Semites: An Inquiry into Conflict and Prejudice, pp. 74-75.

Herzl published his famous Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State) in February 1896, a little more than a year after Captain Alfred Dreyfus, the only Jew on the French Army’s General Staff, was arrested on charges of being a German spy. Dreyfus’ conviction a month later in a scandalously rigged “trial” was supported by a tidal wave of antisemitic press commentary and anti-Dreyfusard mobs on the streets, which continued over the next decade, despite the miscarriage of justice quickly becoming apparent and ultimately leading to Dreyfus’ acquittal. See: Paul Johnson (1988), A History of the Jews, pp. 379-80.

Semites and Anti-Semites, p. 76.

It was commonly believed at the time—and still is—that the Tsarist government instigated the pogroms as part of a general program to deflect attention from its failings onto the Jews. This is false, as is the claim that the Okhranka, the Tsar’s political police, were the authors of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which first appeared in Russia in 1903, almost certainly imported from France.

Some high officials in Saint Petersburg were personally antisemitic and thought the Protocols were true—though not Nicholas II, notably—but the Okhranka worked diligently and largely successfully up to 1917 to suppress the reach of the Protocols within the Empire for the simple reason that they could incite disorder, which was always and everywhere the main enemy the Imperial Government struggled against. Even Konstantin Pobedonostsev, the ministerial supervisor of the Russian Orthodox Church, a man personally very hostile to Jews, was unalterably opposed to anything that could lead to popular violence.

The 1881-82 pogroms after the terrorist-revolutionaries assassinated Emperor Alexander II caught the Imperial Government completely off-guard: nothing of the kind had been seen for two-hundred years and by terrible coincidence the Okhranka was in the middle of a reorganisation. The 1905 pogroms occurred amidst a massive terrorist uprising. Nicholas II tried to pacify the situation by peeling the liberals off the revolutionaries, signing the October Manifesto that surrendered autocratic power and opened a Duma (Parliament). This largely failed: as ever, the Russian liberals’ attraction to the terrorists proved stronger than their desire for concrete achievements. But traditionalists were enraged and many of them blamed the Jews for forcing the Manifesto on the Emperor. Facing popular violence from Left and Right, the Imperial Government foundered.

In both 1881-82 and 1905, it is fair to say that Petersburg failed to act quickly or efficiently enough to suppress the antisemitic violence, and some lower police officials, especially in Ukraine, did worse than that. But this was an issue of the Imperial Government’s rather limited capacity, not its desire. See: Charles Ruud and Sergei Stepanov (1999), Fontanka 16: The Tsars’ Secret Police, pp. 203-45.

Petach Tikva preceded the organised movement of Jewry to the Holy Land by four years. Established in 1878 by Orthodox Jews, Petach Tikva was developed and made permanent with financial aid from Baron Edmond James de Rothschild.

Neville J. Mandel (1976), The Arabs and Zionism Before World War I, p. 39.

The dedication of the Hashomer became something of a debate among the elite of the Old Yishuv. The young village guards conscientiously and bravely acted to prevent Arabs invading Jewish settlements. The issue was that the Hashomer were suffering terrible—potentially unsustainable—casualties in confrontations where they intercepted Arab bandits, and rather than give up their loot, the Arabs would murder the Jews.

An article in 1911, written by Yitzhak Yaakov Rabinovich, an Orthodox rabbi and political socialist, gives us a sense of this debate—and of the scale of the Arab anti-Jewish violence in the Holy Land already at that relatively early date. Rabinovich tentatively suggested the Hashomer should be reformed so that its personnel were less attentive to Arab raids on Jewish settlements that were intent “only” on robbery, not murder, concluding: “Are we truly so rich in forces that we can sacrifice Jewish life for the sake of a sheaf or a horse?” Rabinovich evidently thought not.

Another moment where the debate flared up was following the murder of Shmuel Friedman, a village guard stabbed to death and hideously mutilated afterwards near Rehovot on 23 August 1913. Writing more bluntly than Rabinovich had two years earlier, Yosef Aharonovitch, one of the leaders of Labour Zionism, Aharonovitch lamented that the young men in the Hashomer were “not capable of distinguishing between the theft of a bunch of grapes and the murder of a person”. The time had come to “loudly proclaim” a “bitter truth”, wrote Aharonovitch: “many of those who have fallen in the fields of our Yishuv in recent years” died due to a mistaken policy of the Jews themselves; this had been a “squandering” of scarce and precious resources.

Moshe Dayan, the famous eye-patch-wearing military commander who helped lead Israel through her first three wars (1948, 1956, and 1967), was named after Moshe Barsky.

Degania Alef, established in 1910, is notable for being the first kibbutz (socialist farming commune), the type of settlement that dominated Israel in its early decades and which still exists in pockets, including near Gaza. It was residents of the kibbutzim who were slaughtered by Iran/HAMAS on 7 October 2023.