Why Does Northern Ireland Care So Much About the Israel-Palestine Dispute?

I came across the mural shown above about the Jewish Legion when I was in Belfast last month. The popular understanding of the First World War in Britain as a whole is at roughly Blackadder levels, so the story of the Legion—a component of the British Middle East campaign, which features (if at all) as a sideshow even in major scholarly works on the Great War—is essentially unknown. Northern Ireland, however, is different, with history in general—whether remembered, recovered, or invented—being much nearer the surface. The mural is an interesting window onto the differing historical-political narratives that form the identities of the two peoples in the Province, the Protestant Unionists and the Catholic republicans, and why it is that both communities feel themselves so deeply invested in the conflict in former Mandate Palestine.

JOHN HENRY PATTERSON AND THE JEWISH LEGION

The focus of the mural is John Henry Patterson, a Protestant born in British-ruled Ireland on 10 November 1867. Patterson’s trajectory before the First World War has strong echoes of Winston Churchill’s colourful early life as an adventurer within, and soldier of, the British Empire.

Patterson joined the British Army in 1885, at age 17, and his first major commission was a decade later, overseeing the Tsavo area in what is now Kenya through which the “Uganda Railway” was being built. Almost immediately after Patterson’s arrival in March 1898, the workers on the rail line began to be preyed upon by two lions. Among the many theories to explain this, there is one obtrusive fact: the Islamic slave trade that the British were trying to stamp out passed through Tsavo on the way to Mombasa, on the Kenyan coast, and the bodies of enslaved people littered the route.1 Whether the lions acquired a taste for human flesh, or the close contact with people led to a realisation of how easy humans were to kill, there is no doubt the lions were unusually persistent in hunting humans, albeit Patterson’s claim the lions killed 135 people is an exaggeration (it was probably more like 35). It was Patterson who brought the reign of terror of the two “man-eaters of Tsavo” to an end in December 1898.

Shortly afterwards, Patterson was deployed to South Africa for the Second Boer War (1899-1902). Decorated for his service and promoted temporarily to Lieutenant-Colonel, Patterson published a book about the Tsavo experience in 1907, which gained him significant fame. Patterson continued on in Africa as a game warden until mid-1908, when he returned to Britain after a tragedy with a hint of scandal.

This meant Patterson was back in Britain just in time for the beginning of what would become by 1912 the Home Rule Crisis. The Catholic majority in Ireland wished to be ruled by a parliament based in Dublin that reflected this demography and the Liberals in Westminster supported them. The Protestant minority in Ireland, concentrated in Ulster in the north, reacted fearfully, declaring, “Home Rule is Rome Rule”. By 1913, both sides in Ireland were preparing to press their political argument through violence, importing weapons to equip paramilitaries. The Catholic-dominated Irish Volunteers were less homogenous, with factional divisions about the end-goal (some of the leading figures were still monarchists). The Protestants, led by Sir Edward Carson, organised the Ulster Volunteer Forces (UVF) to resist the imposition of Catholic-majority Irish nationalist rule, wishing to retain Direct Rule from London and the Protestant Ascendancy. Patterson is believed to have been involved in “Operation LION”—the name is certainly suggestive—which smuggled vast quantities of weapons from Germany to the UVF in April 1914. Three months later the first of a series of German weapons shipments to the nationalist Volunteers arrived.

The Kaiser was non-sectarian in trying to push Britain over the brink into civil war in the months before the Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo in July 1914. Once the Great War began, all of the UVF and a majority of the Volunteers fell in behind the British war effort. As in Russia, where the Germans sponsored Vladimir Lenin’s Bolsheviks, the Kaiser had to rely on the most radical elements for political warfare in Britain. This transpired to be the revolutionary republican wing of the Volunteers, who, with German assistance, staged the Easter Rising in April 1916.2 The myth of that event and its suppression set the stage for the emergence of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) the next year, which would draw on support from the Soviets and the Nazis.

(The paramilitaries that formed in the late 1960s as “The Troubles” began adopted the UVF and IRA labels, but they were separate organisations from those formed in the 1910s, albeit the extant version of the IRA also had—as we shall see—support from the Soviet Union for as long as it lasted.)

Patterson had rejoined the army at the outbreak of the First World War and served on the Western Front for a few months, before being sent to Egypt, where he was on hand to greet the Jews who had been forcibly deported from the Holy Land in December 1914 by the German-aligned nationalist Young Turk junta that had seized control of the Ottoman Empire in 1908. Most of those expelled were foreign-born or foreign citizens, among them two Russian Jews, Joseph Trumpeldor, who had served the Tsar in the 1904-05 war against Japan and lost an arm at the decisive siege of Port Arthur, and Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the future founder of the “Revisionist Zionist” trend that opposed what it saw as the naivete of the socialist mainstream. Trumpeldor and Jabotinsky wanted to create a Jewish military force to join the British war against the Ottomans. This was initially rejected by London and orders were given to have the Jewish volunteers formed into a logistics squad. Trumpeldor accepted this. Jabotinsky did not, and set off for Europe to lobby for the British bring the Yishuv into its camp.

As it happened, three weeks after the 750-man Zion Mule Corps was created in March 1915, about half of it was deployed with British troops, many of them from the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), as part of the daring but disastrous attempt to swiftly knock the Ottomans out of the war at Gallipoli. Casualties for the Zion Mule Corps were reasonably light—it seems thirteen deaths, not fourteen as said on the mural—and for Patterson the real triumph was seeing “the drilling of uniformed soldiers in the Hebrew language” for the first time “since the days of Judah Maccabee” in the second century BC.

The Zion Mule Corps was disbanded in early 1916 and Patterson returned to Ireland, but in August 1917—after eighteen months of lobbying by Patterson, Jabotinsky, and others—the British finally agreed to the creation of a specifically Jewish battalion, into which a hundred or so Corps veterans were folded. The rest of the 1,000 men in the unit, semi-officially known as the Jewish Legion, and more informally as the First Judeans, came “mainly from Jews in the East End of London, or Jewish soldiers who transferred from other regiments”, as the mural explains.

Jerusalem fell to British forces in December 1917, the first time since 1244 the city had been in Christian hands, and the Jewish Legion was an integral component of the Royal Fusiliers as Britain launched its final offensive in the Holy Land in June 1918, culminating at the Battle of Megiddo (or Armageddon) in September 1918. Jabotinsky was one of the leaders in this effort, credited later by the British for opening up Judea, as it was known at the time (“the West Bank” now), and enabling the capture of Damascus.3 Patterson vigorously defended his troops from the various forms of antisemitism shown towards them, from the British High Command and their peers. Patterson’s advocacy at once earned him great respect from the Jewish Legion troops and probably cost him promotion.

In the interwar years, Patterson, now based in the United States, continued to campaign for Jewish statehood in their ancient homeland,4 and tried to gain support for creating and training a Jewish army to resist the Nazis. Patterson died on 18 June 1947, eleven months before Israel was restored. In America, Patterson had been in close contact with Jabotinsky and become friendly with Benzion Netanyahu, a historian and Revisionist Zionist activist, who named his first son, Yonatan (b. 1946), after Patterson. Yonatan Netanyahu was the only Israeli fatality in the 1976 Entebbe raid that rescued the Jewish hostages in Uganda, not a million miles from where Patterson’s career began. Benzion’s second son, Binyamin (b. 1949), the Israeli Prime Minister almost uninterrupted since 2009, presided over the ceremony for Patterson’s reburial in Israel in 2014, during which Netanyahu said: “[Patterson] is the godfather of the Israeli army.”

NORTHERN IRELAND AND THE HOLY LAND

In terms of how this history is remembered in Northern Ireland now, the mural itself is instructive, located at the top of Northumberland Street, just off the Shankill Road, one of the main throughways in west Belfast and the most famous Protestant stronghold, the centre of communal cultural activities like the Orange Lodge parade on the Twelfth.5

To give a sense of the Shankill:

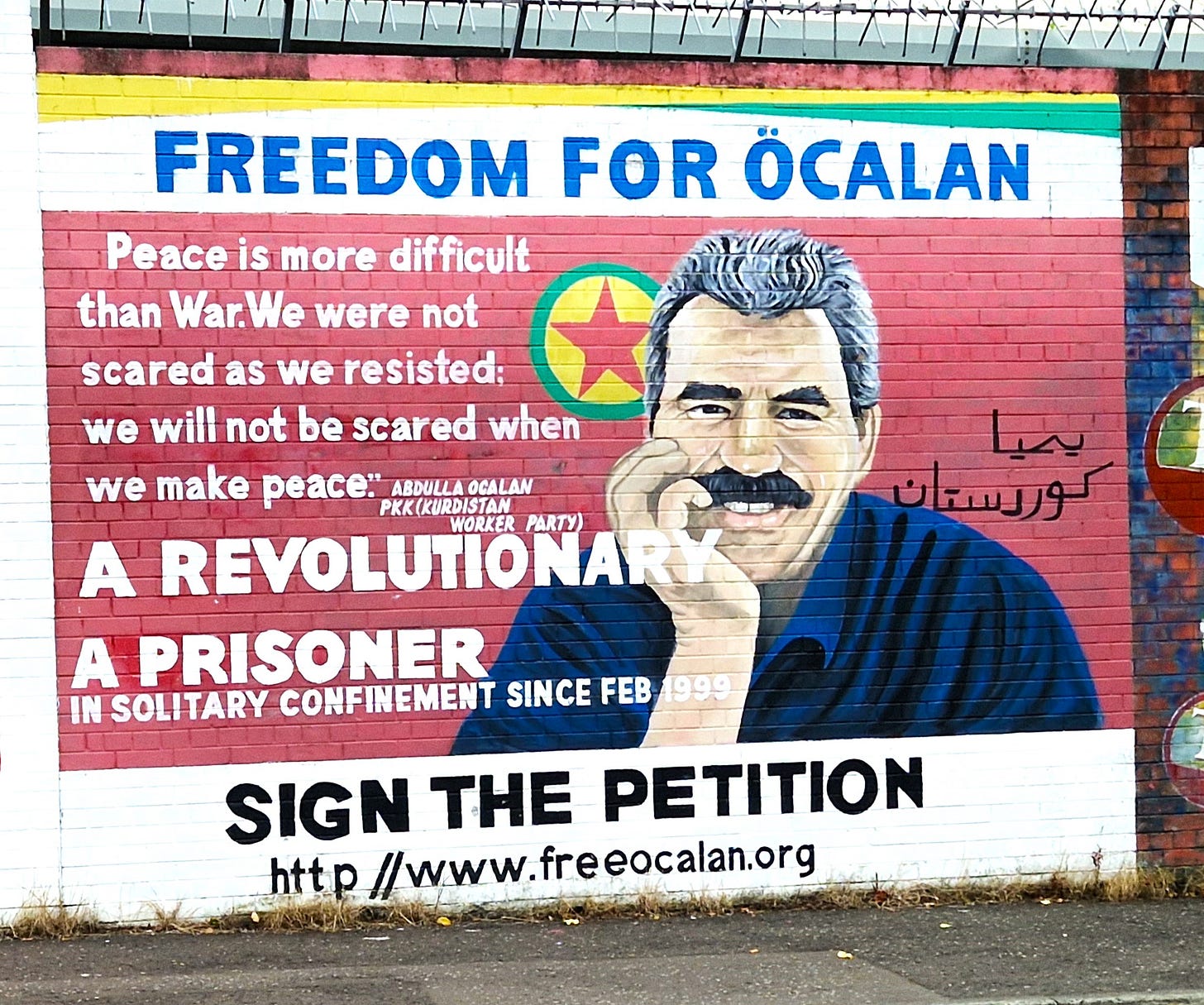

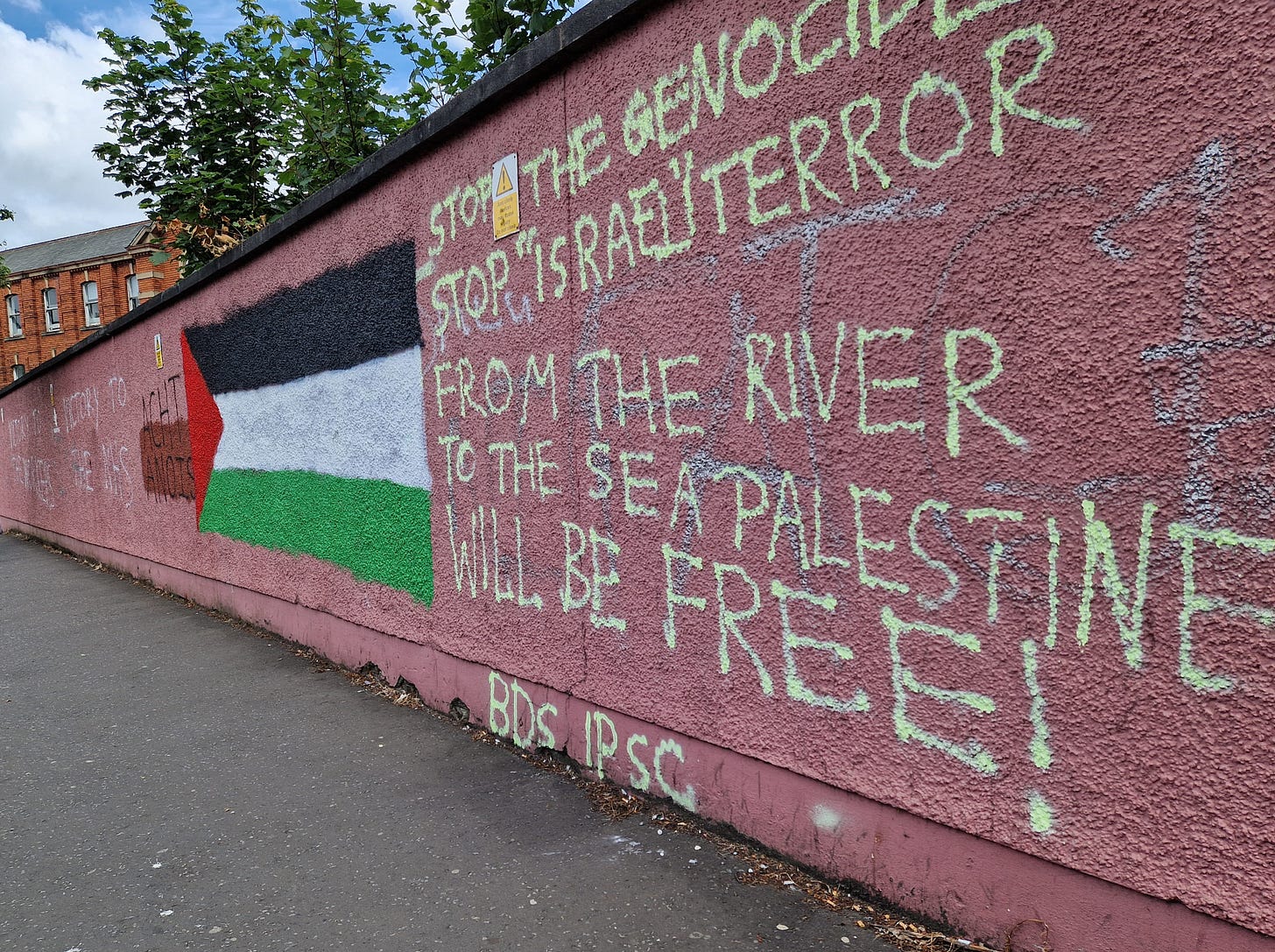

As one walks along Northumberland Street, the posters and street art change from commemorating the shared history of the Irish and the British to Ireland’s links with the Palestinian Arabs and propaganda materials for various revolutionary terrorist groups, such as the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a creature of the Soviet international terrorist network that was significantly administered by the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and once included the IRA (both the Originals and the Provisionals):

When one reaches the intersection beyond Beverley Street, Saint Peter’s Cathedral is directly in front of you, and immediately to your left on Divis Street is this:

A number of private homes on Divis Street were adorned with Palestinian flags. If one turns right and begins walking, one is on the Falls Road, the Catholic nationalist-republican counterpart to the Shankill:

Very different vibes, I think it will be agreed.

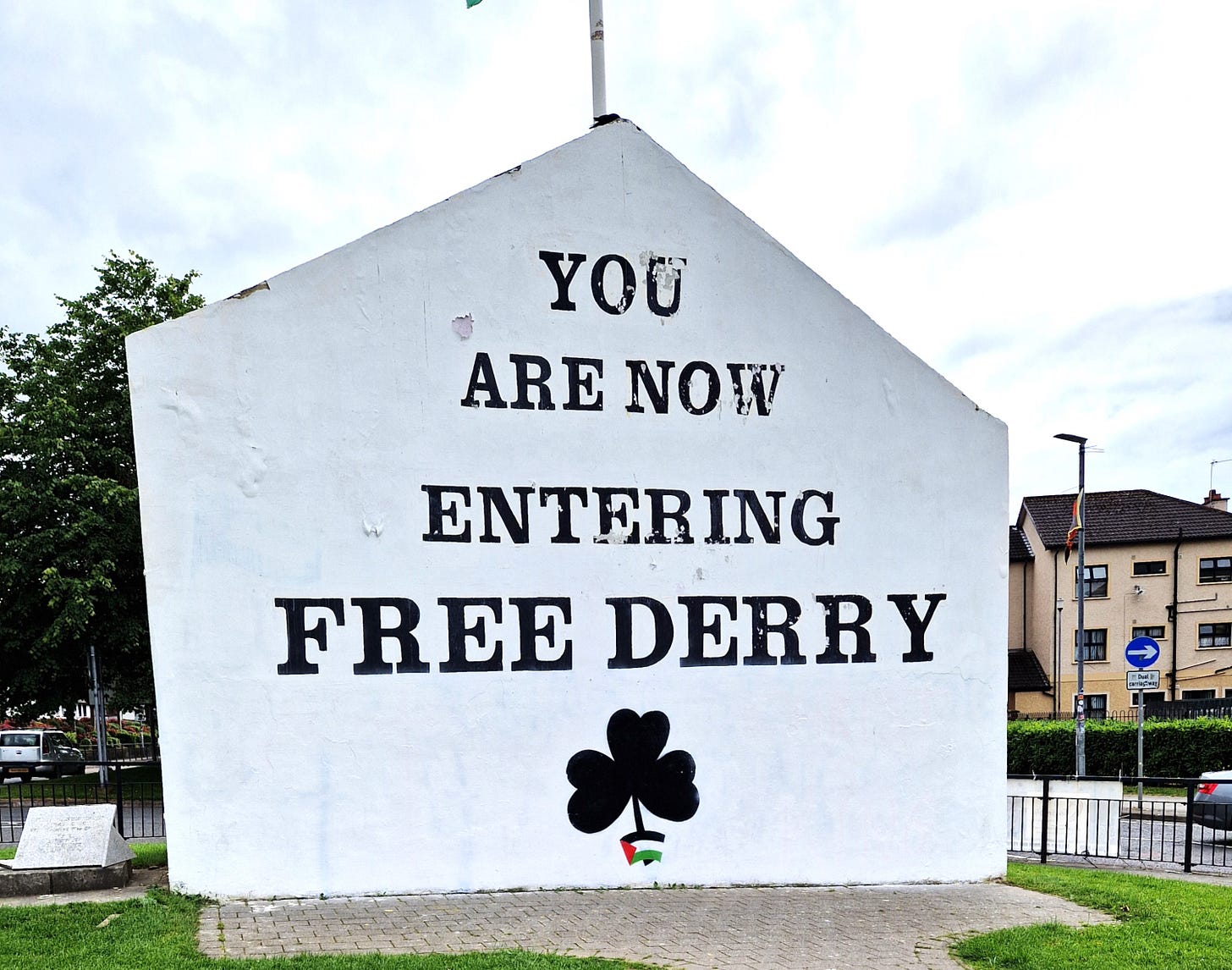

In the largely republican Londonderry, site of the January 1972 “Bloody Sunday” fiasco, the display of Palestinian flags on private homes was even more pronounced, there were Palestinian flags incorporated into all of the official republican shrines, and the “unofficial” graffiti and displays—which popular sentiment at a minimum supports enough that nobody dares take them down—directly advocated for Palestinian terrorist groups, including HAMAS and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP):

So, the battle lines are very clearly drawn: the Protestant Unionists support Israel and the Catholic (at least by background) republican nationalists support the Palestinians, including their most radical and murderous groups. Why is it that such a distant conflict—involving religiously, ethnically, and linguistically different peoples—resonates so powerfully in Northern Ireland?

The IRA, as mentioned above, was a component of the Soviet global terrorist apparat, which brought the Provos into close contact with the PLO, the PKK, the African National Congress (ANC),6 the Basque ETA, and many other Moscow-loyal “national liberation movements”, as well as the clerical regime in Iran and its Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), specifically the Lebanon-based IRGC unit, “Hizballah”. The Iranian theocracy worked closely with the Soviets in the 1980s and has had an ever-tightening strategic relationship with the Russian Federation since the 1990s. The public face of the republican movement reflected the milieu in which the IRA/Sinn Fein was covertly moving. (It still does: Ireland has been among the most vocal in supporting the ANC’s political warfare against Israel at the International Court of Justice.)

The IRA phrased the strategic goal of its “armed campaign” in “anti-imperialist” terms, casting Northern Ireland as six counties of the Irish Republic under a British “occupation” they intended to throw off. The reality, of course, was the IRA being supported by Soviet imperialism in a campaign of indiscriminate violence against civilians, in a Province where people have democratic rights, to try to terrorise the majority that wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom into accepting Northern Ireland being annexed by the Republic of Ireland. But reality has little relevance in nationalist mythology, and the IRA was building on a widespread sentiment that positions the Irish not as part of “the West”, but as “indigenous” victims of Western colonialism who have more in common with “the Global South”. Rather than Patterson and the struggle for a Jewish homeland, the historical connection Irish nationalists see between Ireland and Mandate Palestine is British repression, neatly summed up in the deployment of the Black and Tans as gendarmes in the Holy Land.

The problem is that this view of “the Irish” is not shared by a substantial minority of people who consider themselves Irish.7 The republicans were always very hazy about where the Protestants fit in their irredentist scheme, and when the IRA had a chance to assert itself on the point the answer seemed to that the Protestants did not fit at all—they would be ethnically cleansed. One can perhaps begin to see where the Ulster Protestant identification with Israel comes in: a small people, democratic and feeling themselves part of the West, besieged and denied international support or even sympathy for their dead, assailed by terrorists who form the leading edge of a much broader effort to deny the legitimacy of their existence and bring about their destruction, either by physical annihilation or expulsion from their homes.

The Biblical warrant for the State of Israel is a factor for religious Protestants, though their numbers are falling drastically. The Protestant identification with Jews tends less to be as God’s Chosen People these days, and more their shared adversity, for example memories of the Jews sheltered in Ireland after fleeing pogroms in Russia in the 1900s, which in turn lends itself very easily to a sympathetic perspective towards Israel in the aftermath of the hideous Iran/HAMAS pogrom of 7 October.

ISRAEL AND THE REPUBLIC OF IRELAND

These dynamics are reinforced by the hostile relations between the Israel and the Republic of Ireland, which maintains strong ties to republican populations in Northern Ireland. The most obvious embodiment of this is IRA/Sinn Fein operating on both sides of the border.

It was not always like this. Despite antisemitism having always been unusually strong and visible in Ireland—Jews in Ireland suffered a boycott thirty years before Jews in Germany—the pre-State Zionist movement supported the Irish republicans.8 The father of former Israeli President Chaim Herzog (r. 1983-93) was known as “the Sinn Fein Rabbi” for his role in the Irish independence war. And anti-British Zionist terrorist groups like the Irgun and Lehi took inspiration from what the Old IRA had done.

The change came in the 1930s, when Éamon de Valera rose to the leadership of the Free State. De Valera had been a leader of the republican rejectionists, those who opposed the treaty that granted Irish independence at the price of partition,9 and provoked sectarian tensions by declaring Eire a Catholic State. When the Zionist leaders, in the face of the escalating horrors of Adolf Hitler’s Germany, accepted the Peel Commission’s recommendation to partition the Palestine Mandate in 1937, De Valera turned on the Jews: no longer were they the equivalent of Irish Catholics, freedom fighters against British imperialism; now, they were akin to the Ulster Protestants, colonists under British protection.10

The IRA’s wartime collaboration with the Nazis, the Free State transforming popular antisemitism into legislation that outlasted the Third Reich, and the infamous decision of De Valera as Irish Taoiseach—in full knowledge of the Holocaust—to personally convey condolences to the German Embassy upon news of Hitler’s death,11 considerably worsened Israeli-Irish relations, as did De Valera’s subsequent decision to make Ireland into a refuge for wanted Nazi war criminals, notably Otto Skorzeny, the leader of the commando raid to spring Benito Mussolini from Allied captivity in September 1943. Ireland grudgingly recognised Israel de jure in 1963, but has ever since made the “right of return”—the primary instrument of political warfare against Israel’s legitimacy—into a defining theme of its diplomacy, all the more so since 1967, when Israel became custodian of the rest of former Mandatory Palestine in the defensive Six-Day War. Ireland only allowed Israel to open a residual Embassy in 1993, more than a decade after it became the first European Union State to call for a Palestinian State.

Rock bottom seemed to have been reached when Ireland’s then-Foreign Minister, Brian Cowen, visited PLO chairman Yasser Arafat in June 2003, at the height of the terrorist Intifada that Arafat had launched against Israel in response to being offered a Palestinian State, and hailed Arafat as “the symbol of the hope of self-determination of the Palestinian people”, while praising Arafat’s “outstanding work … tenacity, and persistence”. Not even the routine hysteria out of Dublin during each flare-up in Gaza since 2008 has been able to top that, and one might have thought the savagery of 7 October would temper the Irish government this time. Not so. The most serious challenge to Cowen’s title of Worst Diplomatic Gesture During a Crisis was launched in November by the current Taoiseach, who declared, after the release of a nine-year-old Irish-Israeli taken hostage for fifty days by HAMAS, that the girl had been “lost” and was now “found”.

CONCLUSION

The answer, then, to the apparent mystery of the distant Israel-Palestine dispute being such a potent issue on the island of Ireland is that, for many Irishmen, events in the Holy Land are bound up with their own sense of identity. What is happening geographically 3,000 miles away is felt emotionally as a personal matter, and, since Northern Ireland and the Republic are democracies, these views are reflected in domestic politics and foreign policy.

NOTES

Patterson remarked on the presence of the bodies along the Arab slave trail and the lions scavenging on them in his memoir, published in 1907.

Richard Pipes (1990), The Russian Revolution, p. 391.

There were no boundaries between what is now Israel/Palestine and Syria in 1918. What subsequently became Mandate Palestine was carved out of Ottoman administrative sub-districts that were part of Syria, which is why the only “national” identity that had any currency among Arabs in the Mandatory area, right down to its extinction in 1948 and for a couple of decades beyond, was “Greater Syrianism”.

Patterson does not seem to have used this formulation, but Ronald Storrs, the first British governor of Jerusalem, did write in a 1937 book that Britain should favour the return of the Jews to Zion because it could create “a little loyal Jewish Ulster in a sea of potentially hostile Arabism”, and some Zionist activists in this period were arguing—albeit without much success, it should be noted—to get Britain onboard for the restoration of Israel by saying it would be a “loyal Jewish Ulster” that could take its place as a pillar of the Empire alongside the Dominions of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. See: Bernard Lewis (1986), Semites and Anti-Semites: An Inquiry into Conflict and Prejudice, p. 177.

The Twelfth, marked on 12 July, now celebrates the “Glorious Revolution” (1688)—the deposition of the Catholic James II and his replacement with the Protestant William of Orange—and in particular the Boyne (1690), the battle in Ireland where King William III, as he was by then, defeat the French-backed forces of the fallen James II.

Originally, however, the Twelfth commemorated the 12 July 1691 Battle of Aughrim, the truly decisive battle in the Williamite War (or First Jacobite Uprising), possibly the most lethal battle on the British Isles, which killed 7,000 men, split roughly evenly between the Williamite and Jacobite sides. (For contrast, at Marston Moor in July 1644, the largest battle of the English Civil Wars, just over 4,000 were killed, almost all of them Royalists, and Naseby eleven months later, which sealed the Royalists’ fate in the First War, was minor by comparison, with 1,500 dead, two-thirds of them Royalists.)

The increasing emphasis on the Boyne dates to the late eighteenth century, partly driven by Britain’s adoption of the Gregorian calendar in 1752, which moved the Boyne’s date from 1 July to 11 July, but mostly because of the founding of the Orange Order in 1795. Aughrim, a bitterly contested and close-run thing, was less conducive to the purposes of the Orangemen than the Boyne, where William had been personally present, the Jacobites had been routed, and James II had fled back to France after the battle.

While Saint Patrick’s Day (17 March) has become a Catholic republican counterpart to the Twelfth, this is a recent innovation. Saint Patrick’s Day was recognised by the Roman Church in the eighteenth century, became an official holiday in British-ruled Ireland in 1903, and was observed in the official calendar of the Free State, but it was a low-key event until “The Troubles”, i.e., after the 1960s. Interestingly, there was a short-lived effort by the Orangemen to annex Saint Patrick’s Day in the 1980s, since it celebrates the conversion of Ireland from paganism to Christianity.

From the late 1970s, the IRA helped the ANC—an entity indistinguishable from the Soviet-run South African Communist Party (SACP)—with bomb-making at the KGB-overseen camps in Communist Angola. The KGB and its clone services from the East, notably the East German Stasi, were present in these camps to train the ANC/SACP terrorist unit founded by Nelson Mandela and other Moscow loyalists in methods of torture to inflict on enemy captives and counter-intelligence. The IRA proved quite proficient at torture; less so at counter-intelligence. See: Stephen Ellis (2012), External Mission: The ANC in Exile, 1960-1990, pp. 137-138.

The 2021 census showed Catholics outnumbering Protestants in Northern Ireland, 46% to 43.5%, for the first time.

One of the lead instigators of the 1904 Limerick boycott, sometimes called “the Limerick pogrom”, was Arthur Griffith, a journalist at the time, and a determined antisemite, though he was careful to claim he was not targeting Jews as Jews. It was the Jews’ “usury and fraud” Griffith said he objected to [See: Brian Maye (1997), Arthur Griffith, p. 368].

Griffith went on to found Sinn Fein (“[We] Ourselves”) in 1905, an officially monarchist party at inception, modelling its demands for Ireland’s place in the United Kingdom on the 1867 compromise that created the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary. Griffith thought this was the most practical way forward, despite not personally being a monarchist and keeping as associates radicals like James Connolly, a leader of the Easter Rising a decade later. It was that event in 1916 that shifted the political landscape. The rebels released from prison and their sympathisers founded the IRA and captured Sinn Fein in 1917, judging Griffith too “moderate” and replacing him in a mob putsch, two weeks before the Bolshevik coup, with Eamon de Valera, a man Griffith had lambasted as a “half-breed Jew”.

Griffith would have his revenge. In December 1921, Irish independence was granted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty, under condition that the new Irish State include formal allegiance to the British monarchy and exclude the six Protestant counties of Ulster—terms similar to those advocated by Griffith fifteen years earlier. De Valera, the president of the Provisional Government (Dáil Éireann) for most of its existence after the Irish rebellion broke out in January 1919, could not accept these terms. Griffith took over as president in January 1922 to oversee the implementation of the Treaty. Griffith died on 12 August 1922, ten days before Michael Collins was assassinated.

Following the Irish War of Independence (1919-21), the Anti-Treaty IRA fought a civil war (1922-23) against the “Pro-Treaty IRA”—by then effectively the national army of the Free State—and murdered the head of the Provisional Government, Michael Collins.

Shulamit Eliash (2004), The Harp and the Shield of David: Ireland, Zionism and the State of Israel, p. 14.

The only reason there were German diplomats in Dublin for De Valera to visit was that he had, uniquely among the leaders of the Dominions (of which the Irish Free State was then still technically one), declared neutrality at the outset of the Second World War in 1939 and refused to expel Axis diplomats. See: Spencer C Tucker (2016), World War II: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection, p. 858. It was only revealed in 2005 that the Irish President, Douglas Hyde, also relayed official condolences to Germany for the loss of the Führer.

Thanks for summary of Irish-Israel relations. I did not know the details.