When the Soviets Turned Australian Intelligence Inside Out

The ABC’s Four Corners program released a documentary this week, “Unmasking the Australian Spy Who Sold Secrets to Russia”. It revealed that in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Soviets recruited a mole in the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) who was responsible for counter-intelligence, i.e. detecting and neutralising enemy agents. In spy war terms, this is victory.

BACKGROUND OF A SPY

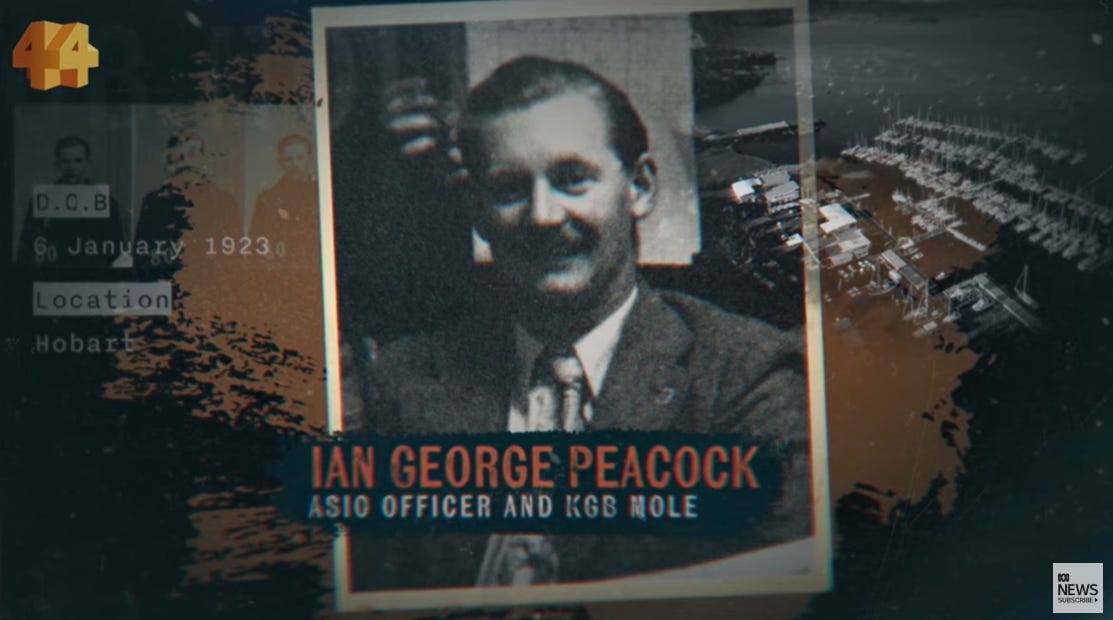

The traitor was Ian George Peacock, 54-years-old when he was recruited in 1977, working as the senior operations manager in ASIO’s Sydney office, where he was head of counter-espionage against the Soviets.

Peacock was born on 6 January 1923 to a well-to-do family in Hobart. Peacock’s father was commadore of the Royal Yacht Club in Tasmania and he attended Geelong Grammar, Australia’s most expensive private school. In June 1941, a then-18-year-old Peacock volunteered for service in the Second World War, enlisting in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). Peacock evidently had something of the spirit of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) about him: he was court-martialled for reckless flying that endangered life during training in Victoria and spent three months in a military prison. Peacock’s father committed suicide in 1949, and Peacock joined ASIO shortly afterwards.

Peacock was one of the earliest recruits to ASIO, part of the “first generation”, often described by subsequent “generations” in ASIO as “old and bold”. There was not really a formal vetting system at that time; such regulations would only come into place later, written by this first generation. In a milieu of informal social screening—based on being from similar classes and the solidarity fostered by the common struggles of Depression and war, most of them having been in the police or the military—Peacock had the advantage that Kim Philby and the Magnificent Five exploited: there was a “one of us” aspect that placed people with the “right” profile above suspicion.

ASIO did not have processes for ongoing reviews of officers, for example keeping an eye on their bank accounts or their psychological state—whether their morale was low or their belief in our cause had been eroded. The former ASIO officers from this time interviewed by Four Corners speak of a boozy, club-like atmosphere, especially when it came to the after-work social scene, which gave an additional layer of cover to any odd behaviours that were detected. The implicit trust within the first-generation cadre made people less sensitive to anything that was a bit “off” among their colleagues, and anything more blatant could be put down to the drink.

Peacock’s career in ASIO initially went very well. He was appointed to the elite new surveillance team, the Operational Base Establishment (OBE), which tracked Soviet spies. Peacock was then posted to Rome for a time with his family, before returning to Sydney. Then things began to go wrong.

ASIO came under attack as the Sixties Revolution made its march through the institutions in the 1970s. Lionel Murphy, the Attorney General (r. 1972-75) for the radical Labor government of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, was deeply hostile to ASIO, and launched an outrageous raid on its headquarters in March 1973, accusing it of unlawful wiretaps. The damage to ASIO was considerable: many of the old guard left, taking their institutional knowledge and expertise with them. ASIO was a demoralised, nearly paralysed agency for many years in the late 1970s, part of the context that allowed the catastrophe with the “Croatian Six” to take place.

Whitlam’s government and party were deeply infiltrated by Soviet agents and agents of influence, many of them run by Gerontiy Lazovik, ostensibly the Second Secretary for Press Information at the Soviet Embassy, who was in reality the KGB rezident or station chief in Canberra (1971-77). We will return to Lazovik. Whitlam was finally removed by Governor General John Kerr in November 1975, a controversial issue at the time that was later cited by Christopher Boyce, an American satellite technician, as his reason for betraying his country to the Soviets for large amounts of money.

The military-style leadership and ethos of ASIO was abolished. A judge, Edward Woodward, was appointed leader in March 1976. What ASIO had valued was declared irrelevant, its practices in keeping the country safe assaulted, and in May 1977 the results of a Royal Commission report set up by Whitlam in 1974 went public accusing ASIO of “illegal” operations. The effect on an already-dispirited ASIO was devastating, not unlike the effects of the Church Committee in the U.S. around the same time, which tamed the CIA into the highly secretive Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency it is today, far more capable of bureaucratic warfare in Washington than anything resembling foreign intelligence work.

The late 1970s was the lowest moment for the West in the entire Cold War. The foolishness of détente had the practical effect of restraining the Western Alliance as the Soviets accelerated the onward march of the Revolution all over the world. Vietnam and most of the rest of Indochina fell under Soviet colonialism. The Soviets’ Cuban bridgehead in the Western Hemisphere nearly captured Chile and did seize Nicaragua, while spreading subversion into Guatemala, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, and in El Salvador caused a terrible civil war. Soviet imperialism rolled through Africa, often with the Cubans as the spear-tip, threatening many pro-Western governments and creating Soviet colonies in Angola, Mozambique, and Ethiopia, among other places. (Red China also took over a number of African states in the same period.) The great Western bulwark in the Middle East, the Shah’s Iran, was destroyed by an unholy alliance of Communists and Islamists, and the Soviet satellite in Yemen tested the security of Western allies and abetted terrorism throughout the region. The culmination came with the Soviets openly conquering Afghanistan. The Soviets made skilful use of the crisis they had created to recruit, often under a false flag, Western intelligence officials who actually wanted to wage the Cold War.

In this situation, men like Peacock became deeply alienated from their societies and state institutions, and there is no doubt this was compounded for Peacock by resentment at the changes imposed on ASIO, which he felt had made the organisation lose its way. Ego might well have been a factor in leading Peacock to treason: his career had stalled out. And all available evidence suggests money was a significant part of his motivation. But even there, it required the context of a society that had abandoned much Peacock and his generation held dear to create such a rupture that he valued financial gain over loyalty to his country.

SOVIET CAPTURE OF AUSTRALIAN INTELLIGENCE

As Four Corners explains, in 1977—the date is unclear but it must have been some time in the spring—the Soviet rezident in Australia, Gerontiy Lazovik, found a letter addressed to him personally in his in-tray, offering classified intelligence in exchange for money, to be paid into a post office box. Attached were samples of the intelligence the would-be agent had access to.

The decision on such a recruitment was above Lazovik’s pay grade, so he sent the documents to Moscow Centre, where they were dealt with by Directorate K, the counter-intelligence division within the First Chief Directorate (FCD), the foreign intelligence branch of the KGB. Among Directorate K’s responsibilities was handling what the Soviets called “precious agents”. The head of Directorate K from 1973 to 1979, General Oleg Kalugin, suspected the approach was a provocation intended to ensnare the Soviet Union in an embarrassing scandal.

To test the validity of the documents, Kalugin turned to Kim Philby, one of the Soviets’ greatest agents. In 1944, Philby was appointed head of SIS/MI6’s counter-intelligence division, Section IX, a belated attempt to reverse the devastating Soviet infiltration of the British state during the Second World War. The wartime “Grand Alliance”, as with détente, was seen by the West as pursuing common interests and by the Soviets as an opening to destroy the capitalist powers. The Soviet victory in capturing the British counter-intelligence system at the dawn of the Cold War allowed them to protect their own agents in the West, to monitor the progress of VENONA so the Soviets could leave agents in place as long as possible and get them out when the game was up (as had happened with Philby’s comrades Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess in 1951), to uncover Western agents or defectors in the Soviet Empire (Konstantin Volkov is a famous case), to sabotage the early “rollback” efforts in Eastern Europe, and to poison the intelligence picture throughout the entire Five Eyes system, keeping attention away from what the Soviets wanted to conceal, feeding disinformation to misdirect analysis and resources, and exacerbating any fissures in the Anglosphere Alliance to try to break it apart, which was (and remains) Moscow’s primary intelligence goal.

Philby managed, officially, to avoid being implicated after the Maclean-Burgess defection, and even managed—despite many in British intelligence being sure he was guilty—to return to work for SIS later in the 1950s. Philby was finally, definitively identified as a traitor in late 1962 and was probably allowed to flee to Moscow in January 1963 to avoid further embarrassments in a prolonged public trial. This is why Philby was on-hand for Kalugin in 1977. To Kalugin’s delight, Philby confirmed that the ASIO documents were genuine. Philby was able to tell they were from Australia, despite Kalugin having removed all markings.

Peacock, who seems to have been the first Soviet mole in ASIO, would become the Australian Philby, turning the Australian intelligence system inside out. Peacock was supervisor-E (espionage) at ASIO’s unit in Sydney, with a security clearance giving him access to the most sensitive top secret and special compartmentalised intelligence (TS/SCI), and responsibility for running the operations against the KGB and its surrogate services in the Captive Nations. Codenamed MIRA (PEACE), for two years Peacock was the main Soviet agent within Five Eyes. Yuri Andropov, the most dedicated, capable, and austere revolutionary in the Soviet elite, the KGB chief from 1967 to 1982 and the General Secretary thereafter until his death in 1984, personally received regular updates on the MIRA case, showing how important it was to the Soviets.

The damage in Australia was extensive. Peacock’s position meant he could (and did) neutralise all actions against the Soviets’ Legal rezidentura or residency, the spy station within the Embassy whose members were officially accredited as diplomats. Peacock sold to the Soviets the details of Australian surveillance targets, ASIO’s methods and practices, and what had been discovered from tapped telephones. A typical case Four Corners documents saw ASIO bug the home of a Soviet military intelligence (GRU) officer under official cover, who suddenly relocated to the Soviet Embassy compound out of reach. By the late 1970s, it had become the norm for ASIO to fail in trying to surveil Soviet Legals.

For the Soviets, however, it was Peacock’s access to the Five Eyes system that made him a goldmine. Pleased as the Soviets were to have access again to the British MI5 and SIS, Moscow’s priority target was always the Main Adversary (Glavny Protivnik), that is the United States, and Peacock had access to intelligence streams from the FBI, the CIA, and most importantly NSA. The local primary target for the Soviets was Pine Gap, the most powerful American signals intelligence facility outside the United States.

Through Peacock, the Soviets could see how Anglosphere security cooperation worked—and how to disrupt it. The same was true of political plans.

The Soviet economy was never more than half as large as the U.S.’s, and it only got that far because of the looting of Eastern Europe after 1945. But the Soviet success in stealing scientific and technological information from the West—which could be used without all the difficulties of ideological “correctness” that meant so much political intelligence was wasted—allowed Moscow to build up a military capacity that posed a global challenge to the American order. Peacock assisted in this by giving the Soviets information on the latest technologies the Five Eyes states were working on.

The information Peacock supplied about his colleagues and, where he could, intelligence officers in other Five Eyes states—photographs, family situations, addresses—allowed the KGB to talent spot potential recruits, to discern vulnerabilities that might make intelligence officers open to recruitment, and to know where to find them and their relatives, through whom, by inducement or blackmail, an approach might be made.

Needless to say, Peacock gave the Soviets everything on Anglosphere agents in the Soviet camp. It is unclear how many murders Peacock is responsible for, though in this sense at least Peacock does not measure up to Philby, who killed hundreds of people.

TREASON AND TRADECRAFT

Peacock wanted to conceal his identity from the KGB and for several months the Soviets only knew their agent as “MIRA”. Lazovik left Australia and returned to Moscow in July 1977, where he was promoted to General and given the Order of the Red Star, one of highest Soviet honours, awarded for great contributions to the security of the Revolution. Lazovik was decorated while his prize asset remained anonymous.

In trying to avoid the Soviets knowing who he was, Peacock was adopting a practice that would be much more successfully employed by Robert Hanssen, the most damaging traitor in FBI history who died in prison earlier this month. Hanssen began passing secrets to the Soviets in 1979, motivated above all by money (another similarity with Peacock). Hanssen intermittently served the KGB (and then the SVR) for two-decades, until his arrest in 2001. Moscow never knew Hanssen’s identity.

Anonymity of agents was never acceptable to the Soviets. As Kalugin is quoted saying by Four Corners: “The KGB runs agents; agents don’t run the KGB”. Hanssen’s position, at the head of the Bureau’s counter-intelligence system, meant he was able to defy this rule, remaining undetected by both sides for a lot longer than Peacock. Lazovik was replaced as Australian rezident by Yuri Shmatkov, who took over as Peacock’s handler and reported straight to Directorate K. While Shmatkov initially struggled to gain the upper hand over MIRA, in late 1977 the KGB mounted a successful surveillance operation against its own agent to discover his identity.

Shmatkov established an elaborate routine for trading documents for cash with Peacock. Shmatkov was smuggled from Canberra to Sydney in a hidden compartment in the boot of an Embassy car. Shmatkov then spent the day at shopping centres and cinemas in Sydney, before taking several buses and trains to ensure any ASIO surveillance was shaken off, collecting the documents from dead letter drops in parks or wooded areas, and leaving the money. Sometimes Shmatkov would save himself the cramped journey in the boot by finding a plausible cover to travel to Sydney, such as joining the staff from the Sydney Consulate for an early-morning group exercise session on Bondi Beach. At a certain point, Shmatkov would peels off for his “dry cleaning run” on the public transport system.

It is very unclear how much money Peacock made from the Soviets. What is known is that the Soviets sent the cash for MIRA every five or six weeks in the form of wads of Australian $50 bills to the Soviet Embassy in Canberra in a diplomatic pouch labelled “tobacco”. This means there were possibly eight dead drops per year and perhaps a total of around fifty, with transfers of vast troves of documents and at least tens of thousands of AUD each time.

By 1979, ASIO became suspicious that there was a mole because its surveillance operations were so regularly crippled without any evident explanation in tradecraft failures. The U.S. reached the same conclusion and began to restrict the flow of intelligence to Australia. A new CIA station chief was sent to Australia to investigate.

The first solid lead in the hunt for Peacock was in mid-1980, from Oleg Gordievsky, the extremely brave KGB officer whose disgust at the crushing of Czechoslovakia in 1968 induced him to risk his life as a British agent in place from 1974 to 1985 to try to bring the Soviet system down from within. (Gordievsky only narrowly escaped being “executed” after his betrayal of the Revolution was revealed to the KGB by an agent of theirs in the CIA, Aldrich Ames.) Gordievsky told the British in 1980 that Lazovik had been given a medal for recruiting an important Australian agent.

The truth of what Gordievsky had said was reinforced when ASIO went to review the Lazovik files and found that all nineteen volumes were missing: not signed out, no explanation, simply disappeared. Extraordinarily, ASIO concluded its investigation by “finding” that the mole was not within its own ranks. ASIO’s highest mission since its founding was the counter-intelligence one, to catch enemy spies in Australia; this was a grotesque failure.

In 1983, Peacock ended his career at age-60, going out on the last day for a drinks party to bid him farewell, an event his former colleagues naturally remember with revulsion now. Peacock had a full state pension, which he collected until his dying day, and retired to play golf at Balgowlah on Sydney’s northern beaches, where he became a director.

FALL OF THE SOVIET UNION AND IDENTIFYING MIRA

After seventy years of destruction and misery imposed on Russia by the Soviet Revolution, and the export of this malady around the globe, the long nightmare finally came to an end on 26 December 1991. The “Socialist Commonwealth” had been dissolved by the revolutions in Eastern Europe in 1989 and now the rump of the Soviet Empire collapsed. In the chaos of the early months of 1992, as Russia and the other fourteen republics freed from Soviet rule began trying to chart a new way forward, starting by dismantling the Cheka’s apparatus of Terror, many KGB officers found themselves in a precarious position. One easy source of revenue was to sell their secrets to Western intelligence agencies. Which is what they did. Among the secrets that passed into American hands was the confirmation there had been a mole in a senior position in ASIO.

The CIA immediately went to Australia to tell the government what it had found, and in March 1992 ASIO set up a mole investigation, pointedly operating outside headquarters.

The critical break in ASIO’s mole hunt came from Vasili Mitrokhin, the then-70-year-old former KGB archivist, who had tried approaching the CIA and been rebuffed. On 24 March 1992, Mitrokhin went to the British Embassy in Riga, where there was an immediate understanding of his importance and the process of securing his defection was set in train.

Mitrokhin is an example of a phenomenon that recurs from time to time in Russian history, of “writing into the table” (писать в стол): keeping records the author has every reason to believe will never see the light of day—and yet he carries on. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn is another famous case. Mitrokhin as an FCD officer had access to foreign broadcasts like the BBC that had helped him see through the lies that sustained the Soviet system. Mitrokhin also understood that the institution he worked for was the engine of repression that kept the Revolution alive. He came particularly to abhor the persecution of religious believers by the militant godless who oversaw the vast concentration camp his country had become. Mitrokhin broke with the Soviet Revolution no later than 1956, when Nikita Khrushchev gave his “Secret Speech” denouncing Joseph Stalin and then sent tanks to crush the Hungarian Uprising. Mitrokhin saw his chance to expose the truth when he was given the task of supervising the movement of the FCD’s archives from the infamous Lubyanka to the new headquarters complex of the KGB at Yasenevo, where the KGB’s SVR successor agency is based to this day. From 1972 to 1984, Mitrokhin meticulously copied down the archives and kept the resulting 11,000 pages of notes in six suitcases under his floorboards, waiting for the day when he could reveal to the world what the Soviets had done.

The crucial evidence from Mitrokhin was a Soviet document written after the retirement of MIRA by his KGB handler and sent to the Centre. The document made clear MIRA had been the supervisor in Sydney, had retired in 1983, been in Rome, and that his wife worked for ASIO. This significantly narrowed the field of suspects from more than a dozen to two. Before ASIO could identify their man, however, there was a minor investigative detour.

George Sadil, an ASIO translator, was seen in Canberra at a service in a Russian Orthodox Church, an institution well-understood to be an extension of Moscow’s intelligence system, in the company of a “diplomat” believed to be a KGB officer. Worse, Sadil was then caught on camera stuffing classified documents into his jacket. In the interview with Sadil conducted by Four Corners, he denies engaging in espionage, and the courts agreed with him: the case collapsed in 1994 when it became clear the documents he stole mostly related to his then-impending retirement. Sadil pleaded guilty to illegally removing documents and was given a suspended sentence. None of the experts or former ASIO officers Four Corners spoke to believe Sadil was a spy, and no evidence has ever been produced to suggest Sadil passed anything to a foreign power.

Thankfully, the ASIO director at this time was determined—as the organisation had not been in 1980—to see the hunt for MIRA through. Time and resources were lost on Sadil, but the investigation was not derailed. Soon ASIO was able to identify Peacock as the traitor, giving him their own codename, REGATTA. Over the next decade or so, ASIO officers met with Peacock dozens of times to try to get him to confess; he refused. A desperate ASIO, having nothing legally admissible against Peacock, at one point offered him a deal in a waterfront restaurant: he would get immunity and a large cash payment if he confessed and helped with their damage assessment. Legend has it that Peacock threw the briefcase of cash in the air and stormed out.

AFTERMATH

Peacock refused cooperation right to the end, dying in 2006 still insisting on his innocence.

For Peacock’s former colleagues at ASIO, the hatred—one of them directly uses that word to the Four Corners interviewer—is understandable. A mole is the disaster intelligence agencies dread, and a mole at the top of the counter-intelligence division is the worst nightmare of all since it places the whole intelligence apparatus in the hands of the enemy. “If you can penetrate the counter-intelligence component of an adversary service, you can control them,” as Dan Mulvenna, a former Canadian intelligence officer, puts it. An ASIO officer who worked with Peacock lamented with fury that “the best years of my life were spent working for an opponent”.

What is most disquieting is that the disaster may not have ended with Peacock. The Mitrokhin Archive discloses that 50,000 AUD were paid to Peacock to identify a suitable replacement. Peacock is known to have approached a young ASIO officer, “Ken”, who refused—but never reported the approach. When ASIO went to interview “Ken”, they found that he had died. The documents show that Peacock told the KGB he had others in mind. If Peacock did find a successor, ASIO does not seem to have discovered him. Doubtless, the successor would also be retired by now, but the same process of selecting the next mole would surely have been adhered to, which leaves open the question of whether a mole remains in ASIO.

ASIO’s investigation after it identified Peacock was written up in the “Cook Report” in 1994. It remains classified. This has had two deleterious effects.

First, it has led to the spread of conspiracy theories, with some believing ASIO was penetrated by half-a-dozen Soviet agents—an absurd proposition, but one which has had very damaging impacts on people’s lives as baseless speculation spreads, some of it driven by personal rivalries within ASIO, about the supposed agents’ identities.

Second, keeping the report secret hampers counter-intelligence work at the present time. Russia is conducting espionage, including active measures and assassinations (the Russians do not compartmentalise these things as Western services do), on a scale not seen since the Cold War, and Moscow’s ally, China, is, if anything, more of a problem, especially Down Under. Intelligence agencies have a terrible problem with institutional memory; they know very little of their own history and continue reinventing the wheel when confronted with problems that, mutatis mutandis, earlier generations solved. It serves no purpose to keep information that can no longer compromise active intelligence operations secret. It would be much better to have the Cook Report’s findings available to scholars and the public to see what went wrong the last time so that there is some hope the mistakes will not be repeated.