The Soviet Union Won the Second World War

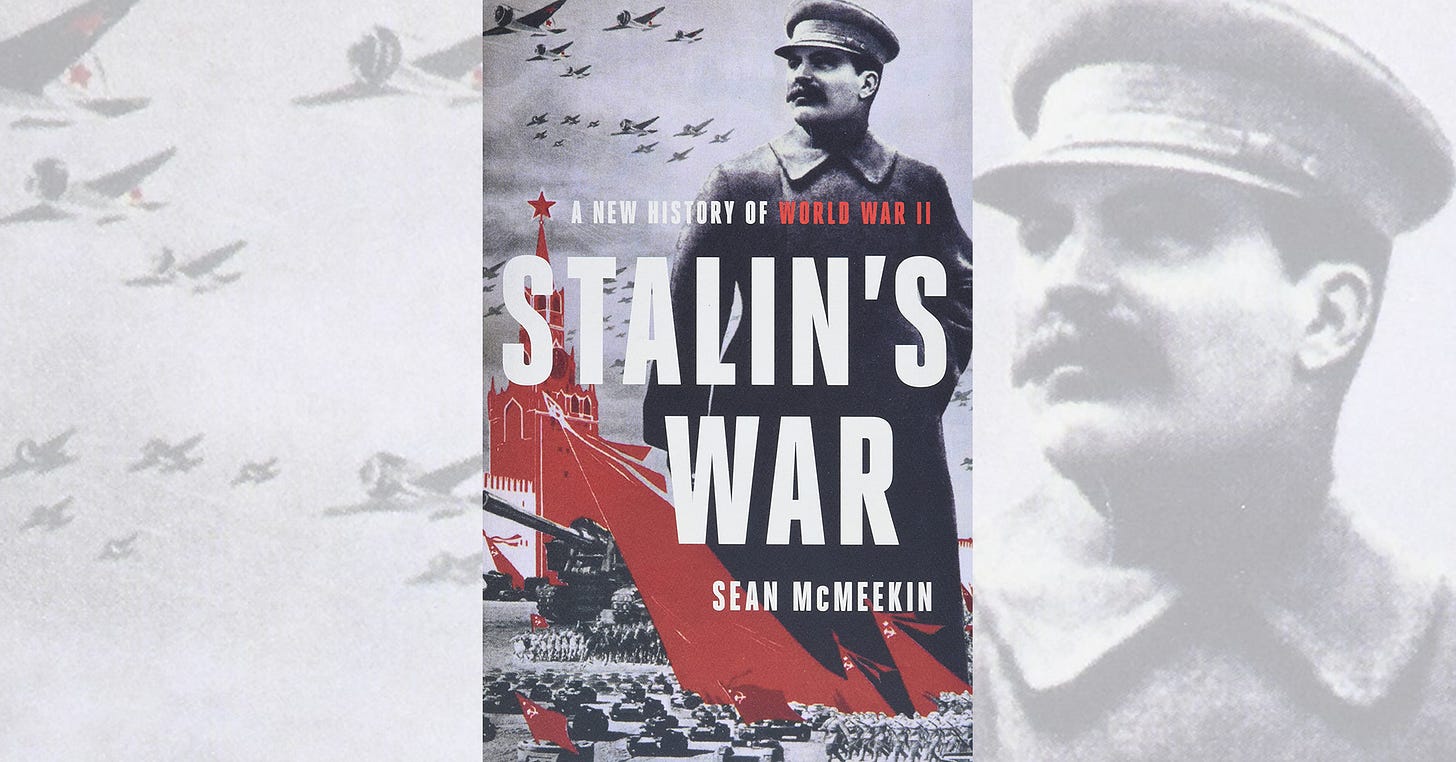

Book Review: Sean McMeekin’s “Stalin’s War”

Sean McMeekin’s Stalin’s War is not, as the author states, “a comprehensive history of the Second World War”, nor is it a biography of Joseph Stalin, though within its 650 easily-readable pages—and 200 pages of footnotes and bibliography—it contains significant elements of both. What McMeekin seeks to do is “re-examine the conflict as a whole”, to situate the “Hitler-centric” war in Europe from 1939 to 1945 that dominates the Anglosphere and Western European memory in its full context, as one part of a conflict on a much wider timescale at either end and over a much vaster expanse of geography. When this “broad lens” is adopted, it becomes easier to see that the main driver of this global conflict is Stalin, not Hitler, and in truth this is “no less visible in narrow focus”: at almost all of the hinge moments, the crucial decisions were made in Moscow. The result might have been a victory, but it was not for the Western Allies.

On a personal note, McMeekin’s synthesis of new archival discoveries, fresh insights from the more well-trodden archives, and revival of older material that was once known but went out of fashion, produced possibly my favourite reading experience and one of the most impactful books I have ever read. The only rival I can think of is Tom Holland’s Dominion, and the reason is the same in both cases: the outline of a realisation I had come to was brought into sharp focus, with the evidence and implications spelled out. The world does not quite look the same after finishing either book.

THE ORIGINS OF THE WAR

McMeekin argues “the Second World War” is shorthand for a series of conflicts that began in September 1931, when Japan invaded Manchuria as part of a contest with the Soviet Union, establishing a line of contact with the Soviets that regularly flared into armed confrontation, including a “small” war in July-September 1939, which in three months killed 8,000 men on each side. (For context, the U.S. lost 2,300 soldiers in Afghanistan in twenty years.) The key fact: the war had begun before Hitler was in power. The “common thread”, as McMeekin puts it, tying together all the war theatres over the next fourteen years across the Eurasian landmass—the man in power throughout the whole period, involved in determining the fate of all of them—was Stalin, the Vozhd (Leader) as he came to be called in the 1930s.

Stalin played a crucial role in Hitler coming to power by ordering the “fraternal” Communist Party in Germany not to work with the social democrats, and after 1933 Stalin continued the covert cooperation with Germany underway since 1922, allowing both sides to build up their militaries. In Spain, Stalin’s men captured the government in 1936 and led the Republicans in the resultant civil war. In the shadow of Nazi Germany and Japan signing the Anti-COMINTERN Pact, Stalin drew the Japanese into an invasion of China in July 1937, and tied them down by supplying the nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) led by Chiang Kai-shek with just enough to keep them in the war, ordering Red Army incursions only when Chiang was existentially threatened, and carefully preserved his own assets, Mao Zedong’s Chinese Communist Party (CCP). And, of course, the conventional start of the Second World War, with the invasion of Poland in September 1939, was a joint enterprise between Hitler and Stalin, agreed in the Secret Protocols of the so-called Non-Aggression Pact signed a fortnight earlier, which divided Europe into spheres of influence between the two totalitarian systems.

The rare mentions of the Nazi-Soviet Pact by Soviet (and now Russian) officials present it as a defensive reaction to the September 1938 Munich Agreement, but this is a lie. Stalin had been angling for the Pact before Munich,1 and he was able to largely set the terms because of Soviet economic leverage over Germany.2 In the obliteration and partition of Poland—a Soviet idea to begin with—the Soviets took the larger chunk; the Germans agreed that all of Finland and Bessarabia (Moldova and eastern Romania) were in the Soviet “sphere”; and Stalin was able to rewrite the terms on the Baltics—which initially gave Estonia and Latvia to the Soviets—to take Lithuania, too. As well as collaborating with the Nazis on the carve-up in the East, the Soviets stood behind Nazi aggression in the West prescribed in the Pact: Stalin “supplied and fueled Hitler’s armies as they invaded Poland, France, and the Low Countries”, writes McMeekin.

Stalin’s hope that “the capitalists”—Germany and her enemies—would wear themselves out, leaving the road clear for Communist armies to take over Europe, was disappointed by the speed of the May-June 1940 Blitzkrieg, but Hitler’s strike West rescued Stalin at the one moment when the Allies were seriously planning to act against the Soviets. The late November 1939 Soviet attack on Finland electrified Western opinion in a way the veiled Soviet involvement in Poland had not. It looked for a moment as if the strange decision to only declare war on one of the violators of the Polish guarantee was going to be rectified now everyone could see the Soviet menace was at least equal to that of the Nazis.3

The British Chiefs of Staff had what McMeekin calls “a flash of strategic insight” just before the Red Army moved in: if Britain took a stand over Finland and gained the public support of the United States—not even as a full belligerent, but of the “moral embargo” kind the U.S. was soon to impose on the U.S.S.R.—this would “decide the attitude of Japan” and Spain, and “probably also that of Italy”, putting them in the Anglo-French camp.4 The map would be redrawn and, as McMeekin writes, it would “transform the so-far desultory and hypocritical British-French resistance to Hitler alone into a principled war against armed aggression by both totalitarian regimes” [italics original]. It was not to be.5

Even within the framework of the Anti-Nazi War, however, “the closeness of Soviet-German cooperation”, as the British War Cabinet noted on 30 January 1940, was so obtrusive that it could not be ignored. Consideration was given to landing Allied troops in support of the Finns and, by mid-February 1940, rumours were all over Europe of a planned British and French air attack on the Baku oil fields from which the Soviets were supplying energy to the Nazi war machine. Soviet intelligence picked up on these plans from their agents embedded at senior levels in Washington and London. This was the heyday of “the Magnificent Five” (the Cambridge spies).

In March 1940, Stalin called a halt to the unexpectedly costly war on Finland,6 and gave the order for the extermination of the captive Polish elite, a massacre of 22,000 men whose bodies were dumped in the Katyn Forest, one of the great crimes of the Soviet Union. At one stroke, Stalin had physically eliminated any basis for a Polish resistance movement the Allies could support and politically cut the ground for an anti-Soviet attack from beneath the Allies’ feet—or so he thought. “However illogical in diplomatic terms, the Allies came closest to waging war on the Soviet Union in the weeks after the Soviet-Finnish armistice”, McMeekin documents. The planned raid on Baku (Operation PIKE) was disrupted by Hitler’s takeover of Denmark and Norway in April 1940 and terminated by the May 1940 Nazi conquest of Belgium, the Netherlands, and France.

As Britain stood alone against the Nazi regime in the summer of 1940, “Stalin … literally fueled the Luftwaffe when it bombed London”, notes McMeekin, and the Soviets had “invaded the same number of sovereign countries since August 1939 as Hitler had (seven)”.7

THE NAZI-SOVIET PACT BREAKS DOWN

The Pact essentially exhausted by late 1940, relations between the Nazis and Soviets began to deteriorate as they competed over Bulgaria and Romania, and Finland became a particular irritant as Helsinki looked to Germany to guard what was left of its sovereignty. The culmination of this was a 13 November 1940 meeting in Berlin where Hitler was pressed on all these points by Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov in a manner the Führer had never had to endure from any foreign official.8 The drinks reception afterwards at the Soviet Embassy—which Hitler refused to attend—was interrupted by a Royal Air Force raid, a proud, if symbolic and unintentional, moment for Britain, attacking the two totalitarian systems simultaneously. This was an embarrassment to the Nazis, belying their claims that Britain was on the verge of defeat—as was the British activity in the Mediterranean after Mussolini’s invasion of Greece on 28 October 1940. But the Soviet attempt to bully and blackmail the Nazis via their economic leverage had hit diminishing returns: Berlin’s patience for relying on Stalin was wearing thin and, with the Red Army’s demonstration of its hollowness in Finland, the Germans felt more confident they did not have to put up with it. The planning since July 1940 for a Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union was formalised into an order to prepare one in December.

In the first half of 1941, Nazi-Soviet tensions continued to rise—over Bulgaria and Romania, and over Jugoslavija, where Stalin recognised and signed a defence agreement with the new government after a British- and American-backed anti-Axis coup in late March 1941. Two weeks later, on 6 April, Hitler conquered Jugoslavija and Greece, bailing out Mussolini’s incompetent forces. The Allied foothold in the Balkans was evicted and, though the campaign was not as costly as either Stalin or Winston Churchill would have liked, McMeekin points out that in many ways the main beneficiary was once again Stalin, as the Nazi invasion of the U.S.S.R. was pushed back five weeks, albeit the Axis now had a more secure launchpad when it came. Throughout this entire period, Stalin was moving the bulk of his military west. On 5 May 1941, the Red Army had shifted to an offensive doctrine, and on 15 May a war plan envisioning a hidden mobilisation and Soviet invasion of the Nazi Reich had been drawn up. McMeekin discusses the “Suvorov thesis”,9 positing that the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union as a preventive or pre-emptive measure, and dismisses it as such—the Nazi war preparations precede those of the Soviet Union.

“[C]onsiderable mystery remains surrounding Stalin’s intentions on the eve of war”, McMeekin writes, but one thing is obvious: “a positively breathtaking ramp-up in Soviet military preparations from April to June 1941”. Whatever was on the Vozhd’s mind, it availed him naught. The bill had come due for Stalin’s conduct under his Pact with Hitler,10 and further mistakes were made in the run-up to zero hour.11 The Nazis commenced Operation BARBAROSSA on 22 June 1941, and within three weeks the military machine Stalin had built up over thirteen years was smashed.12 The fall of the Soviet capital soon seemed a real possibility.

JAPAN AND THE PACIFIC

Even at the darkest moment of the war for the Soviet Union, in the second half of 1941, Stalin’s control of events was evident. Stalin had signed a Neutrality Pact in April 1941 with Japan, a member of the Anti-COMINTERN and Tripartite Pacts with Germany and Italy. If Hitler had coordinated BARBAROSSA with the Japanese, Soviet defeat would have been assured. As it was, a well-placed Soviet spy in Tokyo, Richard Sorge, was able to tell Stalin in mid-September 1941 that Japan would not open a second front, allowing the movement of eleven Soviet divisions from the Far East for the defence of Moscow. If Hitler’s policy towards Japan has an explanation, it probably lies in a mixture of overconfidence that the “Judeo-Bolshevik” structure would crumble swiftly after merely “kick[ing] in the door”, and an agreement with Stalin that “Anglo-Saxon capitalism” was the main enemy: there was Nazi-Soviet agreement that it was more strategically useful for Japan to “strike south” (against British and American interests in the Pacific), rather than “strike north” at the Soviet Union.

Stalin did not leave such things to chance. After Japan moved into Indochina on 26 July 1941, with the formal “authorisation” of the Nazi puppets in Vichy France, the U.S. imposed a de facto oil embargo. Japan’s ambassador made an offer to U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull on 6 September that, in exchange for a lifting of the embargo, the Japanese would withdraw from China “as soon as possible”, except the Manchuria/Manchukuo province adjacent to the U.S.S.R.; refrain from “military advancement” in French Indochina; and foreswear “any military action” against British Malaya, Dutch Indonesia, or the American colony in the Philippines. Japan also made it clear it did not feel itself bound by the Tripartite Pact to join Germany or Italy “in case the United States should participate in the European War”. Three days later, Hull rejected this without even a counter-offer, and by 14 September Sorge was able to report from his Cabinet source that Japan would not be going to war with the Soviets, but was seriously considering war against the Americans.

Japan made one final peace offer on 15 November, with slightly improved (for America) terms, and a back-up offer of at least a truce and withdrawal from Indochina that began a negotiating process over China. Stalin was alarmed at President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s (FDR) interest in such a course. A Soviet agent at the U.S. Treasury, Harry Dexter White, wrote a memo saying this would be a “Far Eastern Munich” and proposed ten, obviously unrealisable points Japan had to meet for any deal. White’s points were a nearly verbatim copy of instructions he had been given by his NKVD handler in May as a component of Stalin’s effort, begun with the Neutrality Pact signed weeks earlier, to bring about a Japanese-American war. White’s terms, packaged into the “Hull Note”, were passed to Japan on 26 November, duly interpreted as a hostile ultimatum, and Emperor Hirohito was informed on 1 December that Prime Minister Hideki Tojo’s Cabinet had unanimously decided Japanese interests could not be obtained from America via diplomacy. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour was launched on 7 December 1941, along with simultaneous Japanese invasions of the British Empire and America’s Pacific territories.

While working to bring about this catastrophe for America, Stalin had been rechristened in America (and Britain) from Hitler’s ally, a “fellow mass murderer and swallower of small nations”, as McMeekin so accurately puts it, into a victim—and an ally.

THE ALLIES ENLIST IN STALIN’S WAR

Stalin was less pushing at an open door in acquiring FDR’s support: FDR directed Stalin’s attention to the fact there was a door and held it open for him.13 Stalin had never asked for the friendship of “the Anglo-Saxons”, as he told Japan’s ambassador in April 1941, and he continued to regard these “imperialists” as his main enemy, eternally plotting to destroy him. As a result of this mindset, the Soviets repeatedly found themselves utterly bewildered at the cravenness of their American interlocuters.14 The more surprising aspect is how far this naiveté and sentimental selflessness affected the apparently hard-bitten anti-Communist Winston Churchill.15

The overriding strategic fact after 1941 was that America and Britain thought of themselves as partaking in a “Grand Alliance” with the U.S.S.R. to defeat Nazism, while Stalin saw the new openness as an opportunity to bring down the capitalist powers from within. Lenin is supposed to have said the capitalists would sell the Communists the rope with which to hang them. McMeekin acidly notes that “not even Lenin could have imagined that American capitalists would hand over the rope free of charge”.

FDR’s “moral embargo” lasted only a month—it was lifted in January 1941, despite no change in Soviet conduct—and in February a “liaison committee … to coordinate strategic exports” was set up. After BARBAROSSA began, the floodgates of American Lend-Lease—the program to assist anti-Nazi combatants—were opened to the Soviet Union, providing the crucial “margins” that prevented the fall of Moscow. U.S. assistance to the Soviets dwarfed anything given to Britain, and, unlike Churchill, Stalin got it for free.16 American materiel being sent to the Soviet Union was deeply controversial on Right and Left in the U.S., but Stalin was rescued once again by Hitler, who recklessly declared war on the U.S. four days after Pearl Harbour, demolishing the heretofore powerful America First Movement and the footing of the isolationists in Congress trying to keep the U.S. out of Europe.

McMeekin writes a lot about Lend-Lease for the simple reason that it is such a salient feature of the war after 1941, and, within its various components, it provides such an illuminating window into what was going on.

The issue of Soviet espionage is unavoidable here. Soviet spies had infiltrated the British government in key positions, notably with Kim Philby’s rise in 1944 to head the Soviet desk of counter-intelligence at SIS/MI6, effectively placing the entire British intelligence system under Soviet control. This disaster was abetted by Churchill’s softness on Stalin, and FDR’s greater gullibility—only at the very end, just before his death in April 1945, did the President begin to see anything nefarious in Stalin’s intentions—had a commensurate effect on America’s handling of the Chekists. Soviet agents infiltrated the American State on an absolutely staggering scale under Roosevelt, in his own White House, infamously in the atomic weapons program, as well as in every major government department and the intelligence services. The public revelations in the late 1940s about how badly the Soviets had compromised America triggered the anti-Communist crackdown that will forever be associated with the word “McCarthyism”.

The influence of Soviet spies over Lend-Lease directly is slightly complicated, since some interpret the VENONA documents as showing that the program’s director, FDR’s right-hand man Harry Hopkins, was a Soviet spy. Others conclude Hopkins was unconsciously co-opted by Soviet intelligence. It comes to the same thing in practice and McMeekin focuses on what is uncontested: FDR via Hopkins created a situation where Soviet spying was unnecessary. Recruiting agents to get access to U.S. military intellectual property and then creating Soviet versions was out; barely-concealed Soviet intelligence officers “inspecting” U.S. weapons and factories in what would previously have been considered industrial espionage was in. “Inspection” results were sent to Stalin and orders were filed with Hopkins. Lend-Lease shipments to the U.S.S.R. followed on such a scale that it caused serious shortages in numerous areas for the Americans during the first year of the war.17

When spies like White had information to pass on, or suggestions for Stalin’s next wish-list to Hopkins, there was no need for cloak-and-daggers: White could just walk over to the Soviet Embassy. Everyone supported “Uncle Joe” now, even if the non-traitors premised this on the false assumption he was on their side, too.

HOW THE SOVIETS MANIPULATED AMERICA AND BRITAIN

To see how the U.S. and Britain carried out Stalin’s bidding at crucial moments during the war, we can look at the examples of China and Jugoslavija. In both cases, Soviet spies played important roles.

FDR met Chiang and Churchill in Cairo in November 1943. The set-up of this meeting, taking place before the first of the “Big Three” conferences in Tehran, was a testament to the lengths Britain and America were prepared to go to keep Stalin happy. Chiang was commander of “an army of four million then-tying down thirty-five Japanese divisions” or 80% of the Japanese Army, McMeekin notes, yet he “was demoted to a sideshow, uninvited to the main summit” because Stalin remained so devoted to the letter of his Neutrality Pact with Japan that he would not be in the same country as Chiang. The vast amounts of American Lend-Lease lavished on the Soviets induced no scintilla of reciprocity.18 The Vozhd would not even make the small humanitarian gesture of handing back American pilots downed over Soviet territory during bombing runs against Japan, sixty of whom were being held in harsh conditions in camps in Uzbekistan.

At the Cairo meeting, FDR verbally promised Chiang that the U.S. “would stage an amphibious operation via the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal (Operation BUCCANEER), in coordination with a Chinese offensive from the north and a hoped-for British push overland, to reopen the Burma Road for supplying China”, McMeekin explains. Once the Burma Road was open, America would send “enough war matériel … to equip ninety Chinese divisions indefinitely, helping Chiang defeat the Japanese and … Mao’s Communists … Everything in China’s future depended on this Burma operation.”

BUCCANEER would never take place and a large part of the explanation is sabotage by Soviet agents at the U.S. Treasury, namely the aforementioned Harry Dexter White and the liaison with Chiang’s government, Solomon Adler. White and Adler were present at Cairo and Tehran—odd enough for relatively minor officials, and stranger still since Secretary Hull was excluded—but they managed to coordinate political warfare, from Washington D.C. and Chungking, respectively. The two Soviet spies wrote near-identical reports that absurdly accused Chiang of “collaborating” with the Japanese—the truth was that Stalin had signed a secret non-aggression deal between Mao’s Communists and Japan in October 1940—and being corrupt, recommending that the paltry $200 million in U.S. Lend-Lease earmarked for the KMT (no more than 2% of what was being sent to Stalin) be withheld unless Chiang “democratised” by bringing Mao’s Communists into his government. Another Soviet spy at the Treasury, Frank Coe, would help make these talking points into U.S. government policy.

Stalin’s man in Jugoslavija, Josip Broz Tito, was pro-German at the time of the conquest in April 1941: the Nazi-Soviet Pact was still operational and Tito was in Croatia, which the Nazis occupied by invitation of the Ustasha. The main anti-Nazi resistance force was led by Draža Mihailović, whose mostly-Serb Chetniks answered to the Royal government-in-exile. Tito’s Partisans only began fighting the Germans months later, after Stalin ordered them to amid Operation BARBAROSSA. It is a testament to the endurance of Soviet active measures that the Chetniks have a reputation for at best behaving atrociously and ineffectively, and more often as outright collaborators, when the reality is that this description better fits the Communist Partisans. The German cables could not be clearer: they had to deploy tanks at times to counter Chetnik operations, and the Chetnik violence was very skilfully targeted at the Nazis and their collaborators. The Nazis felt little military and even less political pressure from the Communists, whose insurgent activity, when it occurred, was indiscriminate and futile.19

Mihailović was undone in the same way as Chiang, by well-placed Soviet agents, whose disinformation colours the historiography to the present day. The British appointed a Jugoslav Communist, known as “Charles Robertson”, to Mihailović’s headquarters, and “Robertson”, in control of the radio link to the Special Operations Executive (SOE) station in Cairo, began a campaign to attribute Chetnik victories to the Partisans and smear Mihailović with the Moscow-origin charge that he was collaborating with the Nazis.20 In Cairo, the recipient of “Robertson’s” slanted reports, who ensured they were passed on to London as if they were gospel truth, was James Klugmann, a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain (eventually its official historian) and one of the recruiters of the Cambridge Five. On top of that, one of the Five, Guy Burgess, was in charge of the BBC radio broadcasts about Jugoslavija, where he reinforced Soviet messaging with increasingly overt pro-Partisan coverage that fostered a cult around “Marshal Tito”.21 When Mihailović complained about this, the BBC’s defence, as ever, was that it was being “impartial” by attacking neither Mihailović nor Tito. One shrewd BBC official recognised the silliness of this, when Soviet agitprop was openly attacking Mihailović as a “traitor”—and the “disastrous” effect this was having on Chetnik morale.

Mihailović had been fighting a two-front war for eighteen months when Tito ordered the Partisans in late March 1943 that “our most important task now is to destroy the Chetniks”. The British would help them. In June 1943, British weapons began to be airlifted to the Balkans, the majority soon going to the Partisans, who were unable to acquire much from the Soviets. The July 1943 Anglo-American landing in Sicily, which brought down Mussolini and secured the anti-Hitler victory at Kursk,22 was the beginning of the end for the Chetniks. At just the moment the Chetniks were making their most serious advances to date against the Germans in August-September 1943, the British ordered them to stand down and negotiate with the departing Italians. Daring Chetnik operations like the blowing up of the bridge near Visegrad were misattributed by the BBC to the Partisans, and when the Chetniks were forced by the British to hand over liberated areas to the Partisans this was duly reported by Stalin’s agents at the BBC as a Communist success. Churchill sent a military mission led by Fitzroy Maclean, and this ostensible conservative anti-Communist had a series of chats with Tito before reporting that the Chetniks were no good. A more accurate field report was slow-rolled by Klugmann in Cairo, arriving in London at the end of November 1943, by which time Churchill had already been won over by the torrent of Soviet disinformation. The British abandoned the Chetniks and committed to doing Stalin’s work for him in the Balkans.

THE ENDGAME

By the time of the Tehran Conference (28 November – 1 December 1943), Stalin had the war well under control. Lend-Lease had saved Stalin from the consequences of his alliance with Hitler, and the American supplies had increased in 1943 after it was clear the Soviet Revolution was safe, enabling Stalin to begin planning the takeover of Reich territories to the west. The political cover for this expansionism was contained in FDR’s unilateral declaration of unconditional surrender as the war aim at Casablanca in January 1943, itself an attempt to mollify Stalin after FDR had not been able to make good on his reckless promises of April and May 1942 to open a second front before the end of the year. Churchill had unwittingly already ensured Jugoslavija would be Stalin’s. Churchill and FDR had even intervened forcefully in public in April 1943, when the Nazis discovered the bodies in Katyn, to support the Soviet lie that the Germans were responsible.

Stalin had given nothing for all these concessions, and this was a deliberate choice. FDR told an aide, “if I give [Stalin] everything I can and ask for nothing in return, noblesse oblige, he won’t try to annex anything and will work with me for a world of democracy and peace.” The only crumb Stalin threw to Roosevelt was, in May 1943, dissolving the COMINTERN, the coordinating body for the Communist Parties committed to World Revolution, “freeing” FDR from domestic pressure against his policy of giving Stalin everything he wanted by those who noticed that the Soviets remained officially committed to overthrowing the U.S. government. “Of course, as Stalin privately explained to Molotov and the Politburo, this was a purely tactical move”, writes McMeekin: the British and American governments were serving Stalin’s interests so well by 1943, he saw attempting to replace them with Communist regimes as “counterproductive”.

At Tehran, Stalin’s fears the two capitalist powers would gang up against him proved wildly misplaced. It was Churchill, now fully absorbing Britain’s faded status, who found himself outvoted at every turn by FDR’s lock-step loyalty to Stalin.23 FDR casually sold out Poland: the details were finalised at Yalta in February 1945—after FDR had accepted Polish-American votes for his re-election. And China was given up, ironically because Churchill had begun to see the danger and made a last-ditch attempt to reroute resources from the Pacific for his Mediterranean strategy that would have utilised the half-million troops already in Italy and landed more in the Balkans to liberate at least Jugoslavija, Romania, Hungary, and had Western forces to push into Germany from the south. While proposed to Stalin as alleviating pressure on the Eastern Front, the Vozhd understood it would limit his imperialism in Eastern Europe and, therefore, virulently opposed it. FDR joined with Stalin in vetoing a Mediterranean campaign, but felt he had to give Churchill something, so, already being pushed by Stalin’s agents at Treasury to cut Chiang adrift, called BUCCANEER off. Thus, China was surrendered to Communism without compensation. Churchill’s cynical “Percentages Agreement” with Stalin in October 1944, and America waking up to the Cold War, rescued Greece in the end, but all else was lost.

The final communiqué from Tehran secured Stalin’s main aims. The U.S. and Britain were committed to opening a second front as quickly as possible and doing so via Operation OVERLORD, an amphibious landing in northern France that would confront the most heavily fortified Nazi positions the furthest distance from Berlin. Stalin had also scotched the Mediterranean campaign that would have attacked weaker Nazi defences closer to Germany: Anglo-American troops in Italy and Jugoslavija were marked for transfer west, for Operation ANVIL. In this way, Stalin ensured there would be no American or British troops in place to block his takeover of Eastern Europe and the Balkans, and that the Anglosphere troops would be so bloodied by the time they reached Germany that there would be no political will to contest the Red Army’s conquests.

To make doubly sure of this latter aspect, Stalin reneged on his promise at Tehran to launch a diversionary anti-Nazi offensive simultaneous with OVERLORD. The Soviets, indeed, took something of a break from fighting the Nazis altogether during OVERLORD: when the Warsaw Uprising erupted, the Red Army halted its advance to allow the Nazis time to suppress it, the start of a general program where the Soviets made the destruction of those brave enough to resist the Nazis their first priority in the zones where they displaced their former allies.

FDR had, amazingly, agreed that Stalin would only break his steadfast friendship with Japan three months after the war in Europe was over, and Stalin would be compensated by the addition of Sakhalin, the Kurile Islands, Manchuria, and Korea to his Empire. Some in the U.S. administration complained at the logic of paying the Soviets—for any Red Army intervention would be “largely with Lend-Lease war matériel sent to Siberia”—to annex the areas occupied by Japan in acts of aggression that had defined U.S. policy in the region since 1931, a moral and political horror that would involve the destruction of the U.S.’s Chinese nationalist allies, with little benefit to the war against Japan, even in terms of saving U.S. lives. And under the new President, Harry Truman, such concerns got a hearing. At the final “Big Three” conference in Potsdam (17 July – 2 August 1945), Truman actually played something like hardball with Stalin over Japan, which saved Hokkaido and South Korea, but the resumption of the briefly-interrupted Lend-Lease deliveries to the Soviets undermined Truman’s leverage, allowing the Red Army to take much of what FDR promised Stalin, despite the atomic bombs bringing about a faster-than-expected end to the war.

In the months after Tokyo’s surrender in late 1945, Stalin used Lend-Lease supplies and the war booty captured from the Japanese in Manchuria and elsewhere to build up his CCP divisions and reignite the Chinese civil war. The Truman administration might have been less naïve about Stalin, but it had not yet taken his measure. Instead of intervening to support Chiang, the U.S.’s nominal ally, against a ferocious Communist onslaught, Truman—influenced in part by Soviet agents in the State Department—ordered Chiang to stop fighting and form a coalition with Mao, then cut off all aid to the Chinese nationalists in September 1946 when this did not happen. This was six months after Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” speech in Fulton that brought the Cold War the Soviets had waged against the West since 1917 to wide notice, and six months before Truman accepted this reality and proclaimed his “Truman Doctrine” to “support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures”. Truman implemented his policy in Greece and Turkey; it was not applied to China.

The astonishing thing is that Chiang managed to hold on for three years after the U.S. betrayed him, a better outcome than in Jugoslavija, where Mihailović was captured by the Communists in March 1946 and shot in July 1946 after a show trial that repeated the fabricated accusations the Chetniks had collaborated with the Nazis. When Peking fell in October 1949, Chiang was able to escape to Taiwan and keep alive the flame of Chinese independence. With China captured, Stalin redeployed his CCP to try to round out his victory in Asia, invading South Korea in June 1950, finally triggering a forceful U.S. and British response to the spread of Communism.

The welcome line drawn over South Korea was far too little, far too late, of course. The Soviet triumph in the rest of Asia had come after the Red Army, gorged on American Lend-Lease, had raped and massacred its way into control of half of Europe, enslaving the populations and plundering the industry and other resources of Eastern Europe to build the Soviet Union into a military peer competitor with the United States that threatened the world in a way Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan never could. The Captive Nations were subject to a relentless war against their societies until 1989—as were dozens of other States from Africa to Latin America—and the war was not over for the West, either, which for that near-half-century had to engage in global combat to contain the devastation wrought by their supposed victory in 1945.

WHAT MIGHT HAVE BEEN

Some of what McMeekin suggests as alternative courses are dubious, for example his criticism of “Churchill’s refusal to parley in June-July 1940, after the fall of Norway, France, and the Low Countries [and] his contemptuous treatment of the [Rudolf] Hess mission in May 1941”, and McMeekin’s suggestion that at least America could have “taken a neutral position on the German-Soviet conflict” is difficult to swallow because of the Holocaust. Whatever strategic sense it might have made for the U.S., and however gruesome it was to rescue Hitler’s co-aggressor from his miscalculations, the Nazis were waging a “war of extermination” by design and treating these invaders the same as the Soviets seems wrong, even if the Allies had adopted the framework McMeekin argues for of a principled anti-totalitarian war.

At the same time, the fact is that nothing was actually done to inhibit the Holocaust while it was underway, and some Allied policies contributed to the death toll, notably Britain blocking Jews returning to the Holy Land after the 1936 Arab Revolt led by the Nazi-supporting Mufti of Jerusalem, Muhammad Amin al-Husayni. Moreover, the one way to definitively stop the Shoah—the destruction of the Nazi regime—was not swiftly accomplished by arming Stalin’s brutal and inefficient army.24 The salutary effects of unconditional surrender on Germany over the long term might be said to outweigh the benefits of supporting the internal efforts to depose the Nazi regime in 1943 and 1944, which were accompanied by offers to the West to ensure the Red Army was kept out of at least Germany and Poland. Perhaps those plots would never have succeeded anyway. But there is a trade-off there, not least because there is no way to know what would have been incentivised inside Germany if it was known the Western Allies were open to a separate peace.

Where McMeekin is most convincing is that, whatever decision was made when the Nazi-Soviet war broke out in 1941, continuing Lend-Lease to the Soviets after 1943, certainly on the scale it was given, was a terrible error. If those resources were devoted to the superior American and British forces, the death camps in the East could have been shut down more quickly, without replacing one form of totalitarianism with another and creating a greater threat to the Allies than the one that was eliminated.

It is all a series of “ifs”, though. If Britain and France had declared war on both aggressors over Poland in 1939, if there had been a war declaration on the U.S.S.R. in defence of Finland and the Anglo-French attack on the Baku oil fields had gone ahead in 1940, if the U.S. had taken more care not to play into Soviet designs over Japan in 1941, if the U.S. had charted a Pacific-first course in alliance with Chiang’s Chinese nationalists rather than a Germany-first course in alliance with the Soviets in 1942, if Churchill had backed the Chetniks to the hilt against the Nazis and the Communists in 1943, if a serious Mediterranean campaign had been launched in 1944. The cascade of changes that result from any one of these decisions going the other way means it is hopeless to try to play out the counter-factual. All we know is what did happen, which is that at every one of these hinge moments the decision went Stalin’s way, and we know the result.

“By objective measures of territory conquered and war booty seized, Stalin was the victor in both Europe and Asia, and no one else came close”, McMeekin concludes. A war fought in the name of defeating aggression and totalitarianism, and for democracy and peace, ended up as “a global war to the death to make much of Europe and Asia safe for Communism”. To summarise this as “the Good War” is inadequate to the point of deception.

NOTES

McMeekin documents that as early as February 1938, Vladimir Potemkin, nominally the “Vice Commissar of Foreign Affairs” but in reality more powerful than Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov, mentioned Stalin’s interest in partitioning Poland to a Bulgarian diplomat. In April 1938, Potemkin wrote openly in a Soviet “theoretical journal” that Poland should be made to “tremble under the hooves of the Soviet columns. … [Hitler] is preparing [Poland’s] fourth partition. Let history be repeated.” Soviet feelers began to be sent out to the Nazis on the subject. The Soviet desire to liquidate and partition Poland had become so pronounced that word of it reached Paris by October 1938, and the next month the idea was overtly suggested in Izvestiya.

In early May 1939, Vyacheslav Molotov became Soviet Foreign Minister, a post he held for the next decade, after Stalin fired Litvinov, a man of Lithuanian-Jewish background, and purged the Foreign Ministry of Jews as part of his outreach to Hitler. Stalin’s antisemitism would turn lethal after the Second World War and a terrible fate for Soviet Jews was only averted by Stalin suffering a stroke in March 1953—on Purim, as it happens. Incidentally, FDR’s effective deputy and Communist-sympathetic liaison with Stalin, Harry Hopkins, warmly defended Stalin purging Jews from the Soviet government. Hopkins only wished a similar purge could happen within the Communist Party USA (CPUSA): he felt the “comparatively high proportion of distinctly unsympathetic Jews” in the Party “misled the average American as to the aspect and character of the Communists in the Soviet Union itself”.

The idea Stalin wanted a “collective security” arrangement with Britain and France is the sheerest nonsense. As Ian Johnson points out in Faustian Bargain: The Soviet-German Partnership and the Origins of the Second World War (2021), what Stalin wanted was territory in the East and “huge quantities of machine tools and military technology”: “The Germans had far more to offer than the British and French.” Even without material considerations, there were “ideological reasons behind Stalin’s preference for a German partnership” over an alliance with the liberal democracies, Johnson notes. Stalin saw the “capitalist world” as hostile, but “divided between ‘rich’ and ‘poor’ States”, with Britain leading the former and Germany leading the latter. Communist theology meant Stalin favoured the “poor” (and revisionist) Germany. The ideological fused with the strategic in Stalin’s primary goal of “avoid[ing] any unity between these two groups, which might result in a capitalist crusade against the Soviet Union”, and instead pushing them into “an extended war”, where “the Soviet Union might profit enormously [by] staying on the sidelines until” they were exhausted. At that point, Stalin could intervene to bring about a victory for Communism.

The Pact, indeed, increased Soviet economic leverage over the Nazis. Most of Germany’s oil, manganese, cotton, and grain came directly from the Soviet Union, and the rubber from Japanese-occupied Asia was delivered through Soviet territory. The Soviet conquest of the Baltic States left Germany at Stalin’s mercy for shipments of iron ore from Sweden across the Baltic Sea. Even without Soviet control of Finland, the source of much of Germany’s nickel and timber, the Nazi State was already well on the way to becoming “a virtual economic vassal of the USSR, with the Wehrmacht’s every forward movement dependent on Stalin’s goodwill”, writes McMeekin.

“Everyone” should not, of course, be taken literally. Leon Trotsky, for example, the great Communist heretic—a man whose supporters, real and imagined, occupied more mental space for Stalin than Hitler, even when the Wehrmacht was at the gates—was fully supportive of a Red Army victory in Finland. Trotsky preferred Stalin’s “degenerated Workers’ State” to either of the “imperialist camps”, by which he meant the Western democracies and Hitler’s Germany. Trotsky’s insistence that Britain and the Third Reich were identical split the Trotskyist movement, and Trotsky’s bizarre and erratic output in his last year before Stalin had him murdered in August 1940 helped further splinter an already fissiparous milieu. One example. Trotsky blamed the fall of France on Stalin’s Pact with Hitler, not because it involved the Soviets supplying material resources to the Nazis, but because it had “abruptly mixed up all the cards”, “disoriented and demoralized the popular masses”, and “paralyzed the military power of the ‘democracies’.” Trotsky was at one and the same time contending that “Stalin played the role of an agent provocateur in the service of Hitler” and rejecting the accusation that “by defending the USSR we thereby defend Hitler” [italics original]. This does not even rise to the level of special pleading; it is just abject incoherence.

Many will bristle at the proposed Allied alignment with Fascist Italy, but it is an order of moral magnitude less horrific than the alliance with the Soviet Union that actually did take place.

Even more strange that the decision over Poland, Britain and France decided there would only be war against the Soviet Union if Stalin invaded Finland and Sweden, the latter of which he had shown no inclination to do.

From McMeekin: “One Finnish ski sniper, a farmer named Simo Häyhä, personally killed, according to legend, more than five hundred Russians. Soviet losses in December 1939 were positively appalling, as high as 70 percent in many units. Wounded Russians overwhelmed the hospitals of Leningrad. One overworked Soviet surgeon complained in early December that he was dealing with nearly four hundred wounded Red Army soldiers every day. … By early January 1940, morale was so atrocious, with Russian soldiers deserting in droves, that [Lev] Mekhlis’s PURKKA agitprop commissars abandoned euphemism and began reporting the truth. In the first two weeks of 1940 alone, Stalin received twenty-two summary reports from the NKVD on army discipline problems.”

These problems did not go unnoticed in the wider world. Britain sent officials to interview captured Soviet soldiers, part of an exploration of whether Stalin’s regime could be destabilised from within. The morale issue was evident enough—most of those interviewed had refused to be sent back to the Soviet Union in prisoner exchanges, knowing they and their families would be shot if they were. “The Russian marches to war with a revolver at his back, and prefers the chance of death at the hands of the enemy to the certainty of death if he refuses”, the War Office officials wrote. But the discovery that the average Red Army soldier was barely literate and chronically malnourished—after twenty years of the Communists’ vaunted literacy campaigns and miraculous harvests from Soviet Science—told against any hopes the Soviet army could form a solid basis for mutiny. The “fatalism” and the Communist crushing of national identity—“Patriotism as such was dead”, the authors wrote—decreased hopes even further. Notably, Christianity was the one thing Soviet POWs “showed a lively interest” in, and which seem to inspire enthusiasm among them, despite the unmerciful persecution of the faithful since 1917. There was some national consciousness among Ukrainians, but even here the cause was largely negative: while the kolkhoz (collective farm) was, “from end to end of Russia, the most hated institution in the land”, the Ukrainians had suffered worst under collectivisation and the famine it caused in the early 1930s, giving them more of a collective identity. The overall conclusion, though, was that “the overthrow of the [Soviet] government can only be achieved by foreign military intervention.”

The Nazis had invaded Poland, Denmark, Norway, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. The Soviet Union had invaded Manchuria, Poland, Finland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Romania.

As this was three weeks after Hitler’s gruelling encounter with General Franco at Hendaye, for the Führer’s interpreter to have judged Molotov’s manner unprecedented, it really must have been.

Named for “Viktor Suvorov”, the pen name of Vladimir Rezun, a dissident Soviet historian who first laid out the BARBAROSSA-as-pre-emption theory in Icebreaker (1990).

There was a sense of panic in Moscow (and even from Stalin some denialism) on the eve of BARBAROSSA, but it was caused by the dawning realisation that there was no time to do anything about errors already made: Stalin’s Pact with Hitler had erased the buffer States that reinforced Soviet defensive lines, the invasions of Finland and Romania created enemies that now joined the Germans, the investment had been in massive airfields and tank parks (rather than more manoeuvrable and defence-oriented weapons), these assets were positioned right out in the open in the border area, and the aggressive actions from trying to blackmail Hitler to the Jugoslav coup had furnished multiple inducements for war.

As war loomed in May 1941, Stalin tried a charm offensive with the Nazis—delivering on stalled oil shipments, for example—and might well have deluded himself that this would forestall the worst result of the German buildup. The Nazis spread disinformation that the build-up was a bluff to exact concessions from Stalin under the rubric of the Pact. The Vozhd was certainly suspicious of the ULTRA intelligence Churchill passed to Moscow about the impending assault, seeing it as intended to embroil the U.S.S.R. in a needless war with Nazi Germany to the advantage of “Imperialist” Britain. That said, as McMeekin makes plain, the narrative that Stalin was shocked by the Nazi attack and had a nervous collapse once it happened is simply a myth, traceable to Nikita Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech” in 1956.

Soviet planes were destroyed on the ground, Red Army troops proved incapable of using the advanced equipment Stalin had acquired from the West, and, in a testament to conditions under Stalin’s rule, Soviet soldiers deserted or allowed themselves to be captured in their millions, despite the NKVD “barrier troops”, the death sentence that fell on POWs, the deportation of their families to the GULAG, and the propaganda—not all of it untrue—about how Slavic captives would be treated by the Germans.

FDR’s affinity for, and wish-thinking about, the Soviet Union defined his whole term in office. FDR had established diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union in November 1933—eight months into his Presidency—during the terror-famine in Ukraine and Kazakhstan, which FDR denied was happening, choosing to believe the notorious New York Times bureau chief Walter Duranty. In October 1936, FDR dismissed Ambassador William Bullitt after he reported accurately from Moscow on the show trials, the opening scene of the Great Terror (Yezhovshchina) that would consume three million lives and send many more to the GULAGs. Bullitt’s replacement, Joseph E. Davies, was as besotted with the Soviets as Hopkins. Davies’ memoir, Mission to Moscow, was produced in 1941 as part of FDR’s publicity campaign to prettify Stalin’s murderous regime, and the book became a film in 1943 that served the same purpose. Roosevelt sacked Robert F. Kelley and abolished the entire Eastern European division he led at the State Department in 1937—down to dismantling its library of Soviet historical and government documents—because the division had continued to produce factual analyses of the U.S.S.R. at the height of Yezhovshchina.

One cannot place all the blame for the U.S. building the Soviet industrial base on FDR—it had begun shortly before he took office—but it was under Roosevelt’s watch that it was entrenched and expanded as official policy, with U.S. government officials sent to Stalin’s slave Empire to “learn” best-practices for the New Deal.

In late 1941, after BARBAROSSA began, FDR removed another sceptical Ambassador in Moscow, Laurence Steinhardt, upon a direct request from Stalin, and the U.S. military attaché in the Soviet Union, Colonel Ivan Yeaton, was cashiered around the same time when Hopkins brought Yeaton’s insufficient Stalinphilia to FDR’s attention. And in March 1943, as McMeekin points out, “the Soviet ambassador to Washington, [Maksim] Litvinov, handed Hopkins a list of ‘objectionable’ diplomats Stalin wanted to purge from the State Department, including Loy Henderson and Ray Atherton from the old Eastern European division.” All were duly pushed out.

An example of Stalin’s confusion when confronting the full extent of America’s authentic commitment to the Soviet cause came in Tehran on 28 November 1943, when FDR finally got his first one-on-one meeting with Stalin, something the President had spent the previous year begging for in increasingly plaintive terms. FDR nodded along as Stalin insulted Chiang and the Free French, and agreed that Indochina should not be restored to France after the war. FDR then volunteered that India should be detached from Britain, and the Americans could work with Stalin to reform India “from the bottom, somewhat on the Soviet line.” Flabbergasted at an American President offering to help bring about a Communist Revolution in the prize possession of the British Empire, it was Stalin who pumped the brakes and told Roosevelt “the India question was a complicated one” that needed to be handled with caution.

Lest one be thought chauvinistic, it should be noted that by this stage the British were little better. Earlier in the month, Britain’s Foreign Secretary Anthony had met with Molotov, shortly after Churchill had abandoned Mihailović in Jugoslavija, and proposed that the Soviets send a military mission to the Communist Partisans the British were now backing. Eden denigrated Mihailović and offered the Soviets “exclusive use of a British air base in Cairo for the purpose”, as McMeekin notes. A clearly astonished Molotov—knowing how different the reality of the situation was from the Soviet propaganda that had informed London’s decision—suggested that it might be worth sending a mission to the Chetniks, too. Eden said the British would not be doing so, but the Soviets could if they wanted to.

Churchill’s anti-Communist reputation dated back to 1918-19, when he had been the one senior Allied figure to substantively support the intervention in Russia to smother Bolshevism in its cradle. (The other Allied leaders saw the Russian intervention as a tactic in the Great War to re-open the Eastern Front.) This was well-remembered in Moscow, but Stalin’s worries were soon dissipated in 1941. The only thing that might be said in Churchill’s favour is that he had begun to realise his mistake by 1944: the fact that a counter-intelligence unit dealing with the Soviets had been set up at all was a testament to this, even if a Soviet agent was appointed to head it.

McMeekin: “At Churchill’s time of dire need in summer 1940, during the desperate juncture after the fall of France when a German invasion of the British Isles seemed imminent, Roosevelt had offered England fifty decrepit World War I-vintage destroyers, in exchange for which Churchill had basically mortgaged the British Empire to Washington. For Stalin, by contrast, Roosevelt had opened a virtually unlimited credit line (initially $1 billion) to order whatever he desired, in exchange for nothing whatsoever. … [S]till more striking was the fact that Churchill himself was going all out to arm Stalin too, at the expense of Britain’s own desperate wartime needs. … In fairness to Churchill, he was under heavy pressure from Washington to agree to all this.”

Weapons, ammunition, military trucks, fighter jets, equipment (rope, machine tools, electrical wire, etc.), food, luxuries such as tea, vitamin supplements, petroleum, metals for Soviet production plants, chemicals (e.g. for explosives and flamethrowers), specialised parts, even braid for Red Army uniforms—all of it was sent to the Soviet Union, tens of thousands of tons at a time, sometimes with whole American factories and all of their intellectual property. Usually Lend-Lease was sent to Stalin by sea—at tremendous cost in money and American lives—but some was sent by air, including obviously the planes. The Soviets were allowed to do some of this themselves. An extraordinary detail McMeekin documents: in June 1942, after a U.S. plane accidentally brushed against an aircraft flown by a Soviet pilot in New Jersey, the Soviets demanded and were granted sole control of Newark Airport. (The Soviet air attaché demanded that the American pilot responsible be executed. Even Harry Hopkins could not comply with that.) Gore Airfield in Great Falls, Montana, had also become a de facto Soviet Airbase by the end of 1942.

In fairness to Stalin—not a phrase one writes often—it might be said that FDR had never asked for reciprocity. The Americans did not condition Lend-Lease or the promise of a second front in Europe on Stalin joining the war against Japan. In the summer of 1941, when it was still unclear if the Japanese would combine with the Germans in the attack on the Soviet Union, Stalin asked the U.S. for a guarantee of intervention in case such a thing should happen; this was granted by the U.S. without any request for a quid pro quo. Had the request been made, it would have put Stalin in a very awkward spot, since he was working to bring about a Japanese attack on America, but, with the Soviet system facing annihilation, the U.S. could have named any price it liked.

A small example from McMeekin: “a German intelligence officer reported from Belgrade on August 28, 1941, ‘[The Chetniks] tend to target German soldiers, or Serbian government collaborators, while avoiding especially cruel atrocities … [It is] entirely different with the Communists. These are pronouncedly asocial elements, who will kill anyone, even harmless Serbian peasants or merchants in the towns, whom they rob. These Communist bands also commit grotesque acts of cruelty.’ Because of such tactics, the German officer observed, the Communist partisans had virtually no support in Serbia, where ‘Broz’ (that is, Tito) was viewed as a bandit and a butcher.”

Georgi Dimitrov at the COMINTERN was the first to make the claim that Mihailović was collaborating with the Nazis.

A lot of what Burgess broadcast about Jugoslavija came from Tito himself, who wired false reports and slanders of Mihailović to the COMINTERN in Moscow, which passed it to the NKVD for distribution to Burgess and other agents.

McMeekin: “By abandoning the offensive on the eastern front to shore up vulnerable German positions in Italy and the Balkans, Hitler had allowed Stalin to claim a legendary victory. Kursk was a decisive battle, to be sure, marking the failure of the last major German offensive on the eastern front in the war. But the victory was, even more than Stalingrad, an Allied one, won as much by the material contribution of lend-lease aid and the complementary US-British landings in Sicily as by Soviet generalship and Russian blood and grit. For neither the first nor the last time, Stalin’s faltering fortunes had turned around because of a timely intervention by his Western allies.”

FDR had winked at Stalin as the Mediterranean (or Italian or Adriatic) campaign was being discussed, indicating that the U.S. would not agree to it and would insist on Stalin’s version of a second front in France: Churchill saw the President. Just after that, FDR teased Churchill in front of Stalin. It was semi-staged effort to win the Vozhd’s affections, and it mostly confused Stalin at first, but he soon realised he was being courted and the benefits to be had by playing along. The most serious moment of tension at Tehran had taken place at the dinner after one of the sessions, when Stalin taunted Churchill about having a “secret liking” for Germany and then proposed to “execute” 50,000 German officers, which caused Churchill to explode in rage that he would have no part in “such infamy”. Stalin calmed the situation by telling Churchill he was joking and then, with his sinister if “oddly disarming” (as McMeekin puts it) sense of humour, turning to his Foreign Minister to say, “Come here, Molotov, and tell us about your Pact with Hitler.” A follow-up of sorts to this line occurred at the gathering at the British Embassy for Churchill’s sixty-ninth birthday, on 30 November 1943. Stalin, as part of the toast, had pressed for details on the “cover plan” to disguise Operation OVERLORD and pointedly suggested that General Sir Alan Brooke, the British air chief, might “come to know us better and find we are not so bad after all”. Brook replied that if he had misjudged the Vozhd it was because of the most convincing “Soviet cover plan” at the outset of the war in “associating with Germany”. Stalin laughed it off.

After 1945, the Soviets would claim in State propaganda to have won the war in the sense of being the primary contributor to the victory over Nazism (which is not true), rather than having won the war in the sense of the Soviets gaining the most from the victory over Nazism (which is true). The argument centred on the claim that the Soviets had done the bulk of the fighting and dying to defeat Nazi Germany. Moscow would ultimately claim that twenty-seven million Soviet citizens (nearly nine million from the Red Army) had perished in the struggle. That number is simply untrue, as any examination of the data that generated it will show. It is likely the figure is vastly inflated, but there can be no certainty in the matter. There is also the more the difficult question of how many Soviet citizens physically killed by the Germans died because Stalin had decapitated the Red Army in Yezhovshchina and then mishandled Hitler, leading to the catastrophic near-collapse in the months after June 1941. It is this question that the “Great Patriotic War” narrative is designed in no small part to repress. Moscow’s official historiography, by portraying the Second World War as having begun out of nowhere with the Nazi attack on the Soviet Union, buries any inquiry into Stalin’s role in setting the stage for Operation BARBAROSSA beneath the millions of Soviet citizens killed in a defensive “anti-fascist war”.