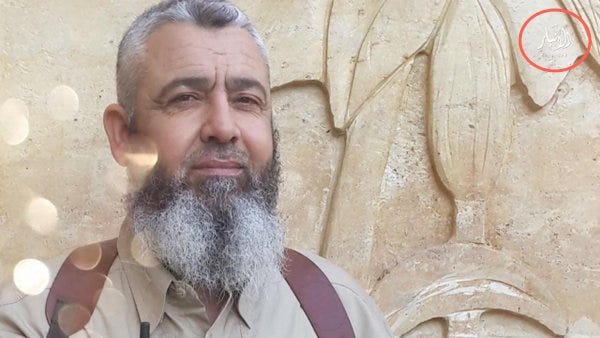

Islamic State Profiles A Towering Figure: Abd al-Rahman al-Qaduli

Al-Naba 41 and 43 give the biography of the elusive Abu Ali al-Anbari

This article was published on my old blog before I started with Substack.

The forty-first edition of the Islamic State’s newsletter, al-Naba, released within the territory of the caliphate on 30 July 2016 and released online on 2 August, and the forty-third edition (released 13 and 16 August), contained a two-part obituary for Abd al-Rahman al-Qaduli (Abu Ali al-Anbari), the caliph’s deputy when he was killed on 24 March. The obituaries, entitled, “The Devout Scholar and Mujahid Preacher: Shaykh Abu Ali al-Anbari”,1 make clear that al-Qaduli was one of the most consequential jihadists in the history of the Islamic State movement. Below is a translation, with some interesting and/or important sections highlighted in bold. The biography resolves some long-standing mysteries, and some of the claims are dubious in light of other evidence we have: these issues, and other points of context and explanation, are in the footnotes. The subheadings are mine, added to signpost the narrative and break it up into more manageable chunks.

BEFORE THE INVASION OF IRAQ

It was God’s blessing that there were various muwahideen [lit. “(strict) monotheists”, i.e., Salafists] in Iraq before the American invasion who bore the burden of spreading tawhid [monotheism] and the combatting shirk [idolatry, polytheism] and bid’a [innovation], despite the tyranny of the kufrs [disbelievers] of the secular Ba’ath regime and its war against Islam and the Muslims. When the Crusaders arrived on Iraqi territory, they [these muwahideen] were a solid wall that stood in their way and, by God’s grace, thwarted their plans, driving them out in humiliation and defeat, and establishing the State of Islam on the Land of Two Rivers [Mesopotamia]. They remained firmly upon that path, some having fulfilled their vow [or term, nahbahu, i.e., been killed], and others God kept alive until He bestowed upon them the grace of witnessing the day when the deen is entirely for God, in an Islamic State ruled by a Qurayshi Khalifa [Caliph] who governs the people upon the Prophetic methodology.2

Of those preachers who followed the way of the prophets in learning tawhid, teaching it to the people, waging jihad against God’s enemies with the sword and spear, [preaching with] proof and clear evidence [al-hujjah wal-burhan], and patiently enduring the trials along this path until they fell as martyrs in God’s path, there was the mujahid shaykh Abu Ali al-Anbari (may God accept him), so we believe of him and God knows best.

The deceased Ba’athist taghut [idolatrous ruler], Saddam Husayn, and his apostate party ruled over Iraq with a pharaonic and tyrannical domination. They did not stop at replacing God’s judgments with man-made laws, but went further in seeking to alter the beliefs of the Muslims [aqa’id al-Muslimeen] by opening the gates for the mushrikeen [idolaters, polytheists] of the Sufis and Rafidites [derog. Shi’is] to propagate their false doctrines, and allowing the spread of atheistic materialist ideologies. At this time, while the people were in the grip of this criminal taghut, Shaykh Abd al-Rahman al-Qaduli (his real name) was proclaiming tawhid from a mosque in Tal Afar, a city west of Mosul. People gathered on Fridays in his mosque until the surrounding streets were filled, thus [alerting the regime and] suffering was brought upon him by the taghut and his secret services.

The threats of the Ba’athists did not intimidate him and did not deter him from jihad, nor did being an only child and the sole provider for a large family with nobody else to care for them, nor the concern for a mosque [that the Ba’athists might desecrate] within whose walls the call to God was being raised. He declared his disbelief in the Ba’ath, declared takfir against everyone associated with it, and incited his close companions and brethren to recognise them as kafirs and fight them. The apostates of the Ba’ath did not tolerate this for long, and soon forbade him to preach or even to call adhan in the mosques. They began to harass him, so that scarcely a month passed without the taghut’s intelligence [services] summoning him.

At that time, the Ba’ath regime in Iraq was becoming weaker after launching a series of unsuccessful wars against its enemies. The muwahideen were expecting its fall and, simultaneously, awaiting the crusader American attack on Iraq to occupy it under the pretext of overthrowing the taghut regime. However, they [the jihadists] did not yet have the strength to build a unified entity capable of bringing down the taghut through decisive battles. Instead, each [jihadi] group began to assemble with their members in given areas so that they could get to know each other, form bonds, and study the deen far from the eyes of the Ba’athists. The result was that several disconnected [jihadist] groups were formed in Baghdad and the surrounding area, in al-Anbar and its desert, Diyala, Kirkuk, Mosul, and Tal Afar, where Shaykh Abu Alaa [al-Afri] (his real kunya) was the elder of his brothers and their shaykh, their source of authority for fatwas and resolutions [i.e., in ideological and practical decision-making]. The activity of Shaykh Abu Alaa was not limited to Tal Afar, where he resided and had previously studied at its shar’i institute. Rather, it extended to other areas of Iraq, especially Baghdad, where he had previously studied at the university. He established relations with the Salafi group of Shaykh Fayez (may God accept him); the muwahideen of Mosul, the main hub [for militant Islam] in northern Iraq; and the mujahideen of Kurdistan, particularly with Ansar al-Islam, which at that time led the only active jihad front in the region and to whom many youths from Iraq and other countries flocked.3

The da’wa [lit. “call”; proselytism] of Shaykh Abu Ala and his brothers in Tal Afar proved fruitful, resulting in numerous benefits. By God’s grace, many of the city’s Rafidites repented at his hands, many repudiated the Ba’athist doctrine, and others who had been in the service of the taghut Saddam—in his army and his security organs [ajhizat amnihi]—dissociated themselves. All of these were fortified by God and later became among the best mujahideen, until God took them as martyrs in His path, so we consider them, but we do not declare anyone pure before Allah [i.e., God knows best].

Alongside his da’wa activity, the shaykh did not neglect jihad in the way of God. He [al-Qaduli] coordinated with the mujahideen in the mountains of Kurdistan and worked with trustworthy muwahideen in Tal Afar to build a jihadist group to carry out military operations against the taghut regime of Saddam Husayn, his Jahili Party, and his apostate soldiers and supporters. The military training of this group was led Shaykh Abu Mutaz al-Qurayshi (may God accept him), one of the repentant officers [dubat al-tayibeen] who had ceased to believe in Ba’athism and had renounced his loyalty to the taghut and his apostate army.4 However, God determined that this group’s efforts would be redirected to confront a greater enemy: the Crusaders under the leadership of America, who invaded the land of Iraq.

AFTER THE FALL OF SADDAM

The Crusader invasion of Iraq had many consequences, including: the collapse of the Ba’ath regime, its army, and all of its security institutions; the spread of chaos throughout the country; the proliferation of weapons among the population; the crippling blow inflicted on the Ansar al-Islam group in Kurdistan, where many mujahideen were killed by American cruise missiles; and the entry of some muhajireen [foreign fighters] into Iraq, taking advantage of the chaotic conditions, among them Shaykh Abu Musab al-Zarqawi [IS’s founder, the Jordanian named Ahmad al-Khalayleh] (may God accept him). It also led to the apostate Ikhwan [Muslim Brotherhood] in Iraq to expose their shirk aqeeda [idolatrous creed] and their kufr manhaj [disbelieving methodology], and to their alliance with the Crusaders and Rawafid.5

Shortly after Baghdad fell into the hands of the Crusaders, many fighting groups were former in Iraq with different ideologies and goals. Among these groups was Jamaat al-Tawhid wal-Jihad, which was established by various groups of muhajireen and ansar [native jihadists] and was led by Shaykh Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and Ansar al-Sunna, which was made up of the remnants of Ansar al-Islam after they relocated [from Kurdistan and Iran] to the cities of Iraq and some muwahideen from other areas of Iraq. The leadership of this group was entrusted to the leaders of Ansar al-Islam, who had come down from the mountains of Kurdistan after losing their sanctuaries.

The Salafi group in Tal Afar was among those who joined Ansar al-Sunna, and soon after began military operations under the name, “The Brigades of Muhammad, the Messenger of God” [Kataib Muhammad Rasul Allah]. It was not long before Shaykh Abu Iman (the kunya that the shaykh used after the Crusader occupation6) was selected as the General Shar’i of Jaysh Ansar al-Sunna. And God decreed that a meeting should take place between the two shaykhs, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and Abu Iman (may God accept them both). Each of them loved the other and rejoiced that the other shared his aqeeda and sound manhaj.7

The common aspiration of the mujahideen in Ansar al-Sunna at that time was to unite the ranks, gather under the leadership of Shaykh al-Zarqawi, and join al-Qaeda. They exerted pressure on their leadership to initiate this, and Shaykh Abu Iman personally sought to organise a meeting with the leaders of both groups [Ansar al-Sunna and al-Zarqawi’s JTJ], at which he succeeded. Shaykh Abu Musab al-Zarqawi met the emir of Ansar al-Sunna Abu Abdullah al-Shafi’i, who refused to unite the two groups using the excuse of needing to consult with his soldiers, despite already knowing their opinion since it was they who were pushing for unification and for Ansar al-Sunna to give bay’a [an oath or pledge of allegiance] to al-Qaeda.8 At this moment, Shaykh Abu Iman announced his bay’a to Shaykh al-Zarqawi and that he had joined al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia.9 Soon afterwards, the bulk of Ansar al-Sunna gave their bay’a [to Zarqawi and al-Qaeda] in what proved to be one of the largest pledges in the history of jihad in Iraq, later to become known as the Bay’at al-Fatihin [Oath or Pledge of the Conquerors].

Shaykh Abu Musab then appointed Shaykh Abu Iman as his deputy in the organisation’s leadership, but before long Shaykh Abu Iman was arrested by the Crusaders and put in the cells of Abu Ghraib Prison. A few months later [i.e. late 2003 or early 2004], God allowed him [al-Qaduli] to be released after He blinded their eyes so they did not find out his true identity and the role he had been playing on the battlefield that was ablaze against them.

The media of the Crusaders led a fierce campaign to defame the mujahideen in Iraq, particularly Shaykh Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and his brothers. The emirs of the misguided groups [or deviant factions] participated in this campaign, as did the leaders of the apostate Ikhwan party, the “[Iraqi] Islamic Party”, especially after the name of Shaykh al-Zarqawi became widely known and the existence of the mujahideen of al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia became a solid edifice against all the treacherous projects of the misguided ones who had declared their apostasy.

What increased the grief of Shaykh al-Zarqawi was the criticism which reached him from the leaders of al-Qaeda in Khorasan,10 which undoubtedly showed that they believed the rumours against the mujahideen in Iraq that were spread by the Crusaders’ media. However, as most of the Iraqi groups exposed themselves early on, revealing their misguidedness, they could not complain about anything except the bad relationship between Shaykh al-Zarqawi and his brothers in Ansar al-Sunna. The leadership of Ansar al-Sunna was in constant contact with Atiyyatullah al-Libi [a.k.a. Atiyya (Abd al-Rahman); real name: Jamal al-Misrati] through Iran, where both sides had lodgings and contact centres [or communications points].11 In light of the sorrow that afflicted Shaykh al-Zarqawi (may God accept him) due to the treatment he received from some of those overseeing Tanzim al-Qaeda fi Khorasan [the Qaeda Organisation in Afghanistan-Pakistan] and their evil thoughts about him, and given the difficulty of communicating with them, he decided to send an envoy to give them the truth about the events in Iraq and to clarify the lies of the emirs of Ansar al-Sunna about the mujahideen.

In the eyes of Shaykh al-Zarqawi, there was no one better suited to this task than Shaykh Abu Iman, since he was his deputy and had great knowledge and status—and was the former [chief] shar’i official of this defamatory group Ansar al-Sunna, thus the most informed about their condition and their internal affairs. Shaykh Abu Iman followed the request of his emir [Zarqawi] and travelled to Khorasan [in February 2006], where he met officials of Tanzim al-Qaeda in Khorasan and explained to them the truth about what was happening in Iraq. Then he returned and presented Shaykh al-Zarqawi on the events of this journey and the results achieved by it.

This was at a time when the American army was reeling in Iraq, and the projects of misguidance were taking shape on the ground [to try to capitalise on the U.S. faltering], every one of them trying to steal the fruits of the jihad in Iraq through the scheming of the satanic Sururis [al-Sururiyya] and the intelligence agencies of apostate Arab governments, especially the Gulf states. The response of Shaykh al-Zarqawi and his brothers was to hasten to develop their own project, one that would unite the best groups in aqeeda and manhaj, including al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia, into a single structure [or framework: itar]. This umbrella organisation was called al-Majlis Shura al-Mujahideen fi al-Iraq [(the Mujahideen Shura Council in Iraq) when it was formed in January 2006,] and it was agreed that the leadership of this Council would rotate among the groups that formed it. Shaykh Abu Iman was chosen as the first emir of al-Majlis Shura al-Mujahideen, and he personally delivered the first statement of this Council under the nom de guerre Abdullah ibn Rashid al-Baghdadi, a name that quickly gained recognition in the media.12

ARREST

In the month of Rabi al-Awwal of 1427 AD [April 2006], God determined that Shaykh Abu Iman would come down from the north [of Iraq] to meet some of the leaders of the organisation, and they would all then go together to meet Shaykh al-Zarqawi in the southern belt of Baghdad. At one of the stations along the way, after they had left the city for the countryside around Baghdad, where they were travelling without weapons because they had been forced to take a route with many checkpoints, the house they were staying in was raided by the Americans. The Crusaders arrested them by God’s design after a battle with a group of istishhadiyeen [suicide bombers], who were staying in a house next door. The compound of the istishhadiyeen was bombed and the guest house of Shaykh Abu Iman and his brothers was uncovered [on 16 April 2006].13 This was one of the heaviest blows inflicted on al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia.

In prison, God blinded the eyes of the interrogators once again and they did not learn the true identities of most of the members of the organisation who had fallen into their hands. But when the Crusaders noticed the respect the brothers had for Shaykh Abu Iman (the Americans called him “al-Hajj Iman” during his time of imprisonment), and the way they [the jihadists] made such an effort to keep accusations away from him [al-Qaduli] and to free him by any means, even if it meant some of them took on the full responsibility [for criminal accusations], their [the Americans’] suspicions about him increased. These suspicions were augmented by the dignity and calm they [the Americans] observed in the shaykh, so they intensified their investigation into his identity, convinced that he was someone important in the organisation. But God foiled their efforts, and the most they were able to ascertain was that he belonged to the organisation. They assumed [in the end] that he was the emir of Tal Afar, since the shaykh had worked almost publicly in that town due to being a well-known presence in the region.

The shaykh remained in prison for several years, during which he was transferred between various American prisons and detention centres, from the south of Iraq to the north. They left him in no single prison for a long time as they saw his influence over the prisoners and the way they gathered around him. After a short stay in one prison, he would be moved to another far away. The Crusaders were about to kill the shaykh in his prison, when a murtad [apostate] was found dead in one of the blocks and they could not find out who was behind it. However, God saved him from their plotting. They did not cease trying to exhaust him by the constant transportation between the prisons, not realising they were serving him immensely because every place where he was transported was a new opportunity for da’wa and teaching. He focused the majority of his da’wa on tawhid Allah fi hukmihi [lit. “the oneness of God in His rule”, i.e., the exclusiveness of God’s sovereignty] and what nullifies it, namely the shirk of obedience [to man-made laws] and the shirk of palaces and constitutions [i.e., governance by secular instruments].14 He would not settle at any new place without invoking the words of Yusuf (peace be upon him): “Oh my prison companions! Are differing lords better, or Allah, the One, the Irresistible?” [Qur’an 12:39].

So the brothers gathered around him [al-Qaduli while in prison] to benefit from his knowledge, and took him as emir and marji’a [lit. “reference”, source of guidance] in all affairs. During this time many of the soldiers of the Islamic State studied under him and among them were two heroes and governors [waliyan] whom God made to torment the Rafida in Baghdad, Manaf al-Rawi15 and Hudayfa al-Batawi16 (may God accept them).

During the time of his imprisonment important events took place in the history of the jihad in Iraq. Shaykh Abu Musab al-Zarqawi (may God accept him) moved to Diyala to prepare the conditions for establishing an Islamic State. However, he was killed by the Crusaders before he could proclaim the founding of the State himself. After him, Shaykh Abu Hamza al-Muhajir [Abdul Munim al-Badawi] (may God accept him) took the lead and announced the dissolution of al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia, and gave bay’a to Shaykh Abu Umar al-Baghdadi [Hamid al-Zawi] (may God accept him), the first emir of Islamic State of Iraq.

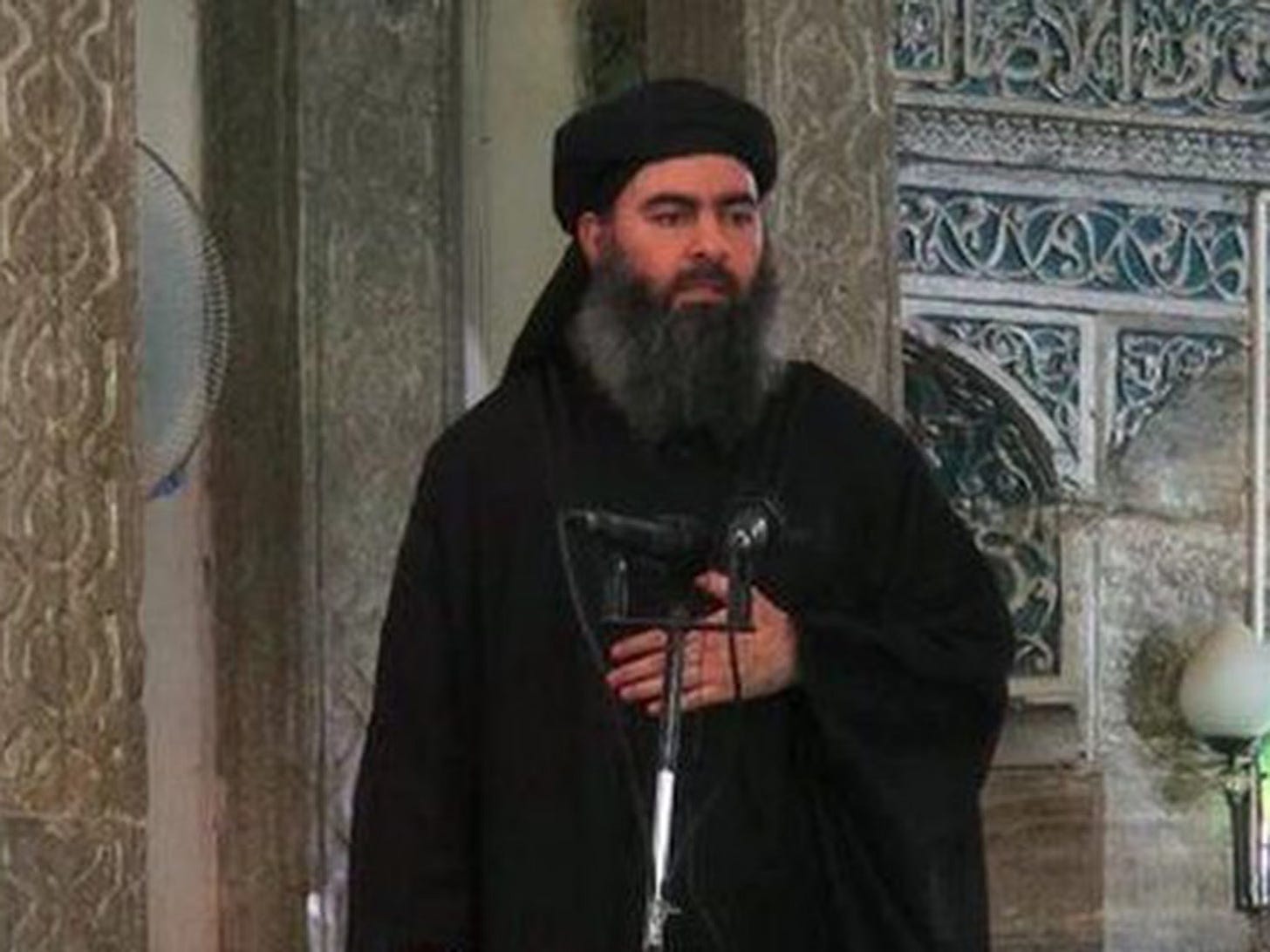

Among these momentous events was the mass-apostasy of the factions and groups that followed the American Sahwat [Awakening] project. The space for the muwahideen was constricted, and large numbers of the mujahideen were killed, eventually including Shaykh Abu Umar al-Baghdadi and Shaykh Abu Hamza al-Muhajir (may God accept them both). The banner was then taken up by Shaykh Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi [Ibrahim al-Badri], marking the beginning of a new stage of the history of the Islamic State in Iraq began.

Shaykh Abu Ali al-Anbari came out of prison [in early 2012] at the beginning of this important stage, where the most prominent feature was the entry of the mujahideen of the Islamic State in Iraq into Syria after a wave that swept many Muslim countries, which became known as “the Arab Spring”. The Islamic State expanded to Syria, thus establishing the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria [ISIS]. Shaykh Abu Ali al-Anbari (may God have mercy on him) participated in the shaping of many significant events until his death, including the establishment of the deen and the return of the caliphate. This is what we will address—by the will of God—in the next instalment of his noble biography. May God accept him..

RELEASE [BEGIN AL-NABA 42]

Among the signs of God’s protection of the jihad in Iraq is that He preserved many of its leaders after the Crusaders and their allies captured them. They [the Americans and Iraqis] threw them in prisons and detention centres, and subjected them to the brutality of the tawaghit, seeking to be rid of them, only for it to be decreed by God that from among them would emerge those who would uphold the deen, and through them God would raise the banner of jihad. These individuals returned quickly to the arenas of jihad, and God used them to revived the battlefronts. They passed on to their brothers years-worth of experience in dealing with the various kinds of mushrikeen and murtadeen [apostates]. Through them, God raised spirits and made feet firm. Among those whom God granted release from captivity to the benefit of the Islamic State was the mujahid shaykh Abu Ali al-Anbari (may Allah accept him).

After six years of imprisonment by the Crusaders and Rafidites, the shaykh was released and found a situation different from that which he left before his captivity. The Crusaders had handed over Iraq to be ruled by their lackeys, the mushrik Rafida, after they [the Americans’] were overwhelmed by their wounds and exhausted by the high cost, and the mujahideen had been withdrawn into the deserts and wildernesses [munahazun fi al-sahari wal-qifar] after a period of glory and tamkeen [lit. “empowerment”; jihadists ruling territory] in which they proclaimed their State and pledged allegiance to their imam. Meanwhile, the other [insurgent] factions had dissolved and completely disappeared after most of them became Sahwat, nullifying all their deeds by falling into the clear apostasy, and the tawaghit regimes had begun collapsing in several countries, heralding a new phase of tamkeen for the deen of Islam, the key to which was the participation of the mujahideen of the Islamic State in the fight against the taghut of Syria, Bashar al-Assad.

When the shaykh came out of prison, he found his brothers who were awaiting him, those who had been with him in al-Majlis Shura al-Mujahideen, and resumed his role in the ranks of the Islamic State in Iraq, whose establishment he had already heard of during his captivity. He was an emir, teacher, and marji’a for its soldiers in prison—every one of those he passed through. Thus, he renewed his bay’a to the Emir al-Mu’mineen [Commander of the Faithful or Prince of the Believers], Shaykh Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (may God preserve him) only a few days after he came out of prison. Immediately he began to work as a soldier in the service of the Islamic State, unconcerned with his past, his former status among students or peers, or even with the knowledge and experiences he had acquired. Instead, he placed himself at the disposal of his brethren, many of whom had been his subordinates before and during his captivity. But his brothers were not the types who deny long-standing bonds, reject beneficence [i.e., the favour shown/goodness done for many of them], and fail to recognise the true worth of men and the value of scholar-warriors [al-ulema al-mujahideen]. So they accorded him the rank befitting such a man, and strove to benefit as much as possible from his knowledge and experience.

The first task that was entrusted to him [al-Qaduli] was to get in touch with the fighting groups outside Iraq, especially with the branches of al-Qaeda around the world, to build communication channels with them after contact had been broken for several years due to the security circumstances. Some of those in charge of al-Qaeda had disparaged the Islamic State, and the brothers believed this was due to the ignorance of the reality [of the situation] on the ground, influenced by the large-scale media assault on the Islamic State’s reputation. Shaykh Abu Ali sent them several messages in which he explained some things to them that he had assumed they had misunderstood. He believed he was addressing people who bore the same manhaj as Shaykh al-Zarqawi: the man he knew, whose manhaj he had agreed with, and to whom he had given bay’a on that basis. These messages marked the renewal of communication between the Islamic State and al-Qaeda and its branches.17

During this time, the soldiers of the Islamic State had achieved a significant presence [in Syria]. Yet alongside the good news of the conquests and victories, there were worrying reports from Syria to Iraq that the leaders overseeing operations there [in Syria] were deviating from the manhaj of the Islamic State, including nascent efforts to appease the factions of shirk and apostasy, general mismanagement, and the presence in the ranks of strongly tribal and regionally partisan elements, which all represented a serious threat that the [Islamic State] project [in Syria] would collapse or be taken over by a bunch of traitors. So the Emir al-Mu’mineen decided to send a representative to assess the situation and to check the accuracy of the reports. He chose Shaykh Abu Ali for various reasons, beginning with the shaykh’s acquaintance with [Jabhat al-Nusra’s leader, Ahmad al-Shara, known as Abu Muhammad] al-Jolani during captivity, as they had been imprisoned together at various points.

SYRIA AND THE SPLIT WITH AL-QAEDA

Back then, al-Jolani had shown the shaykh [al-Qaduli] deference and respect, both in prison and afterwards, even describing him in his letters as “my beloved father.” The shaykh had thought well of him, and viewed the accusations against him in the reports as typical of the kind of quarrels that arise between soldiers and their commanders, or between rival emirs. So Shaykh Abu Ali al-Anbari (may God accept him) went to Syria, crossing the artificial borders [c. November 2012], and this journey was one of the gifts of God to the State. After his arrival [in Syria], he began a tour, which lasted for several weeks, across the various areas of Syria.18 He saw with his own eyes the extent of the errors in the conduct of the leadership, and the deviation that was common among the soldiers and emirs [of al-Nusra]. The root cause was the neglect of shari’a education and military training by those overseeing the work, but he felt that these mistakes could be remedied by more effort.

The shaykh then decided to live in the same quarters as al-Jolani, to be close to him for a while and take the opportunity to uncover the deeper realities [of the situation in Syria], to study his personality, and to assess his ability to lead. Within a month or less [i.e. around January 2013], God showed him [al-Qaduli] many facts that caused him to send a warning to the Emir al-Mu’mineen [Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi], urging him to intervene in Syria to save the situation before it was too late. He sent the letter through which God revealed the truth about the traitorous al-Jolani, reporting on what he saw of him, and giving a precise evaluation of his character. Among the things he [al-Qaduli] wrote in that letter was the following description of al-Jolani: “He is a sneaky person with two faces. He loves himself and does not care about the deen of his soldiers. He is willing to sacrifice their blood just so he gets attention in the media. He leaps with joy like a child whenever his name is mentioned on the satellite [television] channels … ”

This letter was the main reason for the decision of the Emir al-Mu’mineen to come to Syria himself because for him [al-Baghdadi], Shaykh Abu Ali was no liar and was was above the rivalries of peers or disputes between soldiers and their commanders. He [al-Baghdadi] crossed the border despite the great danger and found Shaykh Abu Ali waiting on the other side for him, requesting permission to return to Iraq now that his mission was completed, and his distress at the state of the jihad in Syria that he had witnessed. However, the Emir al-Mu’mineen refused this and took him [al-Qaduli] with him on his journey, to assist in correcting the mistakes that al-Jolani and his faction had committed, and as a helping hand in [bringing about] change.

The attempts of al-Jolani and his group to restrict the movement of the Emir al-Mu’mineen after he came to Syria came using the pretext of protecting him failed. The Emir al-Mu’mineen needed only a few tours among the soldiers and a couple of meetings with the [al-Nusra] emirs to determine that those in charge of the [Islamic State] operation [in Syria] had corrupted the cause and were working for themselves and their [personal] interests, which had a negatively impacted the care given to soldiers and their relations with the emirs. So the Emir al-Mu’mineen summoned al-Jolani and his clique to hear their excuses for what had been proven about them. The well-known [mid-March 2013] meeting took place in which the infamous performance of al-Jolani’s weeping occurred. The dajjal [lit. “deceiver”; anti-Christ] al-Harari [Maysar al-Jabouri, a.k.a., Abu Mariya al-Qahtani (he was born in Harara near Mosul)] insisted on renewing the bay’a to the Emir al-Mu’mineen, and his colleagues responded to the prompt, standing up one after the other to renew their bay’a. By doing this, they hoped to gain some time to complete their project of splitting the organisation and seizing control of men and money entrusted to them [by al-Baghdadi]. But this deception from them did not—by God’s grace—convince the Emir al-Mu’mineen and his Shura Council, and they [ISI’s senior officials] decided to depose al-Jolani and his retainers, and to appoint a new leadership for “Jabhat al-Nusra,” which was the cover name for the mujahideen of the Islamic State in Syria.

However, the could not use this option—the timing was unfavourable—because they found that the traitors had worked too quickly toward their project of breaking the bay’a and declaring rebellion against their imam. Indeed, Al-Jolani had already summoned his closest followers and told them about his plans to split from the Islamic State of Iraq in a conspiracy with the leadership of al-Qaeda in Khorasan. This assembly [where al-Jolani decided to break from the ISI] took place a week after their renewal of the bay’a to the Emir al-Mu’mineen, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (may God preserve him), and news of it soon leaked. Thus, the only option seemingly left for the leadership of the Islamic State was to dissolve the name of “Jabhat al-Nusra” and explicitly proclaim that it belonged [or “was subordinate”] to the Islamic State. Shaykh Abu Ali al-Anbari (may God accept him) was one of the prime movers in pushing this view, which was adopted by the Emir al-Mu’mineen in his famous speech on the dissolution of the names of the “Islamic State in Iraq” and “Jabhat al-Nusra,” and their union under the new name: “The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria” [ISIS]. The traitors were caught off-guard, and they had no choice but to complete their conspiracy against the Islamic State with the participation of the emir of al-Qaeda, Ayman al-Zawahiri. They rushed to declare their bay’a to al-Zawahiri in order to confuse the issue for the soldiers, making it difficult for them to understand what was happening or reach a decision [on whether to stay with al-Nusra or go over to ISI]. This gave the traitors a new opportunity to advance their project.

It was by God’s decree that Shaykh al-Anbari had earned great love and respect from the soldiers, emirs, and students of knowledge throughout Syria during the inspection tour mentioned above. This was one of the things that helped fortify the soldiers of the Islamic State in Syria [i.e., ensure they sided with ISI] during the great Fitna that befell them. A few visits to the areas and districts [of Syria by al-Qaduli] were enough to clarify the truth for most soldiers about what had happened and the reason for the decision to dissolve Jabhat al-Nusra. Thus, the majority of the soldiers remained faithful to their bay’a to the Emir al-Mu’mineen, and the greater part of the organisation was pulled away from the traitors. Only a small number of men, those deceived and the profiteers, remained in the ranks [of al-Nusra], plus a small contingent of soldiers from the eastern region who were tied [by tribal affinity] to the dajjal al-Harari. Taken by surprise again, and with no other recourse, they [al-Jolani and his loyalists] devised the infamous issue of arbitration by al-Zawahiri, which they concocted with him and with the slain Abu Khalid al-Suri [Muhammad al-Bahaya].

Their [al-Nusra’s] rage towards Shaykh al-Anbari (may God accept him), who God had used to mostly thwart their project, led them to plot his assassination, along with some other shaykhs and emirs, as part of a broader plan that involved seizing control of the borders to prevent any connection and communication between the soldiers of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. However, they refrained from trying to implement this plan, fearing reprisals by the soldiers of the Islamic State, knowing its might and the deployment of its security detachments [al-mafariz al-amniya] throughout Syria, and being certain of their ability to reach them and take their heads if they dared [to try to close the Iraq-Syria border].

BUILDING A STATE IN SYRIA AND THE WAR WITH THE SYRIAN REVOLUTION

Shaykh Abu Ali al-Anbari continued his work in Syria tirelessly [in the second half of 2013], serving as head of the Shari’a Council and a member of the General Supervisory Committee [al-Lajna al-Ama al-Mushrifa] overseeing all operations in Syria. This period was of the most difficult in his life (may God accept him), due to the heavy responsibilities placed on his shoulders and the tremendous effort he expended in teaching, da’wa, and research on shar’i issues, in addition to handling regional administration, managing the resolution of problems with the factions and organisations, and overseeing the judges and Islamic courts founded by the Islamic State in the areas where it had gained some level of control. He worked to organise these courts’ operations and put in place regulations to govern their functioning.

Among his qualities (may God accept him) during this phase was that he never gave up calling the factions and organisations to tawhid and the Sunnah. He used to meet with their leaders and warn them of the danger of relations with the tawaghit states and their secret services. He told them that the tawaghit were luring them through [promises of] support and funding to the gates of apostasy and treachery so that they might bring the jihad in Syria under their control, and then to direct them to fight the Islamic State by recruiting them into Sahwa-type projects, similar to those established in Iraq. This was precisely what happened a few months later [in January 2014], as a result of God’s determination, when these factions turned on the Islamic State. The story of their betrayal of the mujahideen in Halab [Aleppo], Idlib, al-Sahel [the coast (specifically Latakia)], and the eastern region [al-mintaqa al-sharqiyya, i.e., Raqqa, Deir Ezzor, and Hasaka] is well known.

After the Syrian Sahwat failed, by God’s grace, and God granted the Islamic State tamkeen over wide areas, constructive work began in earnest to build up the institutions of the State to administer these zones and establish the rule of God therein. Shaykh Abu Ali al-Anbari was at the forefront of directing those who created the Dawawin and [was personally involved in] their foundation, especially the shari’a-related Departments, such as the Judiciary, Hisbah, Da’wa, and Zakat, plus the Office of Researches and Studies [Maktab al-Buhuth wal-Dirasat], which came into being after the Shari’a Council was abolished and its duties were distributed among the Diwans according to subject area [or specialisation].

After God opened up Mosul and vast swathes of Iraq for His muwahideen slaves, and Syria was joined to Iraq by breaking the fictitious boundaries [in June 2014], the shaykh (may God accept him) begged to be released from assigned duties so he could return to where he began his da’wa and jihad, namely the city of Tal Afar. He settled there for a time as just one soldier among the soldiers of the Caliphate. He personally participated in many battles against the atheist Kurds [PKK], the apostate Peshmerga, and the mushrik Yazidis [or Yazidi idolaters: mushriki al-Yazidiyya] on Mount Sinjar and the surrounding areas. Through him, God made firm the feet of the mujahideen in many battles.

But he was summoned again [to a leadership role]. His final station was as the manager of Bayt Mal al-Muslimeen [the House of the Wealth of the Muslims, i.e., the caliphal treasury or finance ministry]. So he settled down in the city of Mosul to carry out this task. He personally oversaw many stages in the implementation of the Islamic monetary project [mashru al-naqd al-Islami], replacing the worthless paper currencies of the tawaghit with metallic coins of real intrinsic value, as is the original basis of wealth. God granted him the joy of witnessing merchants throughout the lands of the Islamic State trading using the gold Dinar and silver Dirham.

DEATH

The Crusaders constantly attempted to track down Shaykh Abu Ali through their spies and planes, and multiple times announced that they had killed him while in fact he continued his da’wa and jihad, carrying the burden of supervising [these duties] without caring about their threats. He continued to meet with merchants, gather with administrators of the Islamic State, travel between the provinces [wilayat], and teach people in the mosques as a khatib [Friday preacher] and teacher, until God decided on his killing by the Crusaders [on 24 March 2016].19 He detonated his explosive belt against a unit of their soldiers who tried to arrest him in a failed airborne operation as he crossed from Syria to Iraq, refusing to surrender his deen in humiliation or please the mushrikeen by his captivity.

Shaykh Abd al-Rahman Ibn Mustafa al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi20 was killed after sixty years of his life.21 Most of that time he spent preaching, teaching, in the ranks of the mujahideen, and behind the walls of the Crusaders’ and apostates’ prisons.

Shaykh Abu Ali al-Anbari was killed as a shaheed [martyr] at the hands of the mushrikeen, departing after his two sons, Ala and Imad, who were slain before him in jihad against the Crusaders. He joins his beloved companions and brothers among the shuhada [martyrs]: Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, Abu Hamza al-Muhajir, Abu Abd al-Rahman al-Bilawi [Adnan Ismail Najem al-Bilawi], Abu al-Mutaz al-Qurayshi, and Abu al-Harith al-Ansari.22 We consider them all as such, but we do ascribe purity to anyone before God from among His slaves.

The killing of the devout scholar and mujahid preacher leaves behind a legacy of knowledge, of calling to the tawhid of God, and warning against shirk in all its forms, especially the shirk of obedience [to non-Islamic authorities], about which he wrote a book and gave dozens of lectures, sermons, and speeches.

May God accept our mujahid shaykh and reward him abundantly on our behalf and on behalf of the Muslims, and may God gather us with him in the highest paradise [al-firdaws al-a’la] with the prophets, the martyrs, and the truthful ones—excellent companions are they.

The post was originally written working from the German version of the third issue of the Islamic State’s ‘Rumiyah’ magazine, published on 11 November 2016. It has subsequently been updated after getting hold of the original al-Naba editions.

NOTES

The title, “العالم العابد والداعية المجاهد: الشيخ أبو علي الأنباري” (Al-Alim al-Abid wal-Da’iyah al-Mujahid: Shaykh Abu Ali al-Anbari), could be rendered as “The Worshipful Scholar and Missionary Mujahid: Shaykh Abu Ali al-Anbari”.

Descent from the Quraysh tribe is the traditional qualification of the caliph from the earliest time of Islam.

Long before the invasion of Iraq, Ansar al-Islam had set up a jihadi statelet—a precursor in many ways to IS’s—in Kurdistan in northern Iraq, covering more than a hundred square miles and 200,000 people. There is also considerable evidence that alongside an official Islamic trend fostered by Saddam Husayn’s “Faith Campaign,” there were robust independent Salafi networks, underground but with strong links to the security sector. Saddam both abetted the growth of the Salafi infrastructure—likely more cynically early on, seeing it as a complementary component to his effort to secure legitimacy via Islam, later in the 1990s it seems from genuine conviction—and was unable to stop it. The Kurdish jihadists and those in Arab Iraq were co-operating, and, as Al-Naba makes clear, al-Qaduli formed an important part of the connective tissue.

Al-Qaduli’s active and open jihadist preaching in Saddam’s Iraq was unusual only in its level of success. Likewise, al-Qaduli conspiring to conduct armed attacks against the Saddam regime was not unique. The first proto-caliph, Hamid al-Zawi (Abu Umar al-Baghdadi), a former policeman of the Saddam regime, had “trained with small jihadi groups in Anbar even before the U.S. invasion”. Umar Hadid (Abu Khattab al-Falluji), a Fallujah native and quite possibly a former Republican Guard, had begun violent attacks on liquor stores and brothels in his hometown around 1997 and then killed a member of the Saddam regime’s security services, which—tellingly—would have been forgiven, if Hadid would have apologised; instead, he went into internal exile and then sought refuge in the Ansar-run area.

“By the late 1990s,” Joel Rayburn records, “some of [the non-governmental] Salafis were conducting a low-level terrorist campaign against the regime that included car bombings and assassinations similar to those that became so common in Iraq after 2003.” Nibraz Kazimi has previously reported the same: “The opening salvo of the Sunni Salafist insurgency [in Iraq] occurred on January 1, 2000, targeting Ba’athists congregating at a liquor store in the Waziriyeh neighborhood of Baghdad, way before any American soldiers appeared on the scene.”

For whatever reason, by the end, Saddam was refusing to move against the Salafi Trend, despite entreaties from his most senior officials who thought the Ba’athists would be overwhelmed if things continued, and the regime was breaking down, limiting its ability to curb the power of the Salafis even if Saddam had given the order. As this obituary of al-Qaduli demonstrates, the jihadists knew it and were prepared for it. Something very like the Islamic State was being incubated in Saddam’s Iraq and would have emerged as a successor force no matter what.

Abu Mutaz al-Qurayshi is also known as Abu Muslim al-Turkmani and Haji Mutaz; his real name is Fadel al-Hiyali. The revelation that al-Qaduli recruited al-Hiyali is especially interesting because when IS expanded into Syria and actually realised the caliphal project announced in 2006, and IS’s number-two Samir al-Khlifawi (Haji Bakr) had been killed, al-Qaduli became the governor of IS-held areas in Syria and al-Hiyali oversaw the territory on the Iraqi side of IS’s statelet. Al-Qaduli and al-Hiyali were “the key people” keeping Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi “in power”. Two of the earliest recruits to the IS movement in 2003 were the crucial deputies to the caliph in 2013-15 in building and sustaining the caliphate. In addition to what this says about Saddam Husayn’s regime—al-Hiyali had been recruited to jihadism while in the army and the Saddam government either couldn’t or didn’t stop him—it is an interesting snapshot of the human element of jihadi networks: this duo of al-Qaduli and al-Hiyali evidently rose together through IS’s ranks.

This refers to the Iraqi Muslim Brotherhood, the Iraqi Islamic Party, cooperating with the American-led Coalition and the Shi’a parties in forming a post-Saddam government.

Al-Qaduli had an extraordinary number of pseudonyms. Abu Iman is not a well-known one but it tallies with one that is, Haji Iman, Iman meaning faith. (This was sometimes given as Haji Imam, which appears to be a mistake.) Abu Ali al-Anbari is the kunya al-Qaduli died under, though he managed to deceive everyone that al-Anbari was a different person to Abu Alaa al-Afri. Al-Qaduli also once took the name Abu Abdullah Rashid al-Baghdadi (a complicated and important story in itself: see footnote 12). Other names included: Abu Jasim al-Iraqi, Abu Umar al-Qardash, Abu Ali al-Qardash al-Turkmani, and Dar Islami.

[UPDATE] IS’s official biography here in Al-Naba in 2016 fairly clearly draws on an account of Al-Qaduli’s life written by his son, “Abu Abdullah al-Anbari”, which was leaked by a dissident “dovish” faction of IS in 2018. It is, therefore, notable that Al-Naba constructs the narrative to strongly imply that the first meeting between Zarqawi and Al-Qaduli took place after the Anglo-American invasion, when Abu Abdullah is quite specific (pp. 33-34) that the meeting took place in Baghdad nearly a year before Saddam was overthrown, around May 2002, weeks after Zarqawi arrived in Iraq. Why IS continues, all this time later, to obfuscate the fact Zarqawi was in under the rule of Saddam Husayn can only be guessed at, but it very obviously is a strictly-enforced messaging decision the group has made.

Al-Shafi’i is also known as Warba Holiri al-Kurdi, and his real name is probably Wuriya Hawleri, though it might be Ja’far Hassan. It was pointed out to me by Brian Fishman that this section of IS’s obituary for al-Qaduli—in which it describes the relationship between al-Zarqawi and al-Shafi’i—is the most factually dubious. IS places the blame for the lack of unity between Jamaat al-Tawhid wal-Jihad and Ansar al-Islam on al-Shafi’i; the record is clear that Zarqawi harboured grave doubts about unifying his forces with al-Shafi’i, not least because the eternal problem of Kurdish factionalism had arisen again. Ansar had been created in 2001 when al-Shafi’i and Najmaddin Faraj Ahmad (Mullah Krekar) sank their differences. In September 2003, with Ahmad physically remote, based in Norway, al-Shafi’i took the reins in a coup d’état, and called the group Ansar al-Sunna (it would later revert to Ansar al-Islam, and in the summer of 2014 was absorbed into IS). It is also reasonably clear that the majority of Ansar did not break away and join al-Zarqawi with al-Qaduli in 2003-04: the most that seems to have happened is that al-Qaduli’s associates from Tal Afar went with him from Ansar to JTJ.

Zarqawi’s JTJ formally transitioned to being “al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia”—formally “The Organisation of al-Qaeda in the Land of the Two Rivers”(Tanzim al-Qaeda fi Bilad al-Rafidayn) and informally “al-Qaeda in Iraq”—after Zarqawi’s bay’a to Usama bin Laden in October 2004, but clearly everyone in the insurgency was aware that for all practical purposes Zarqawi was an al-Qaeda operative from the get-go.

Khorasan designates an ancient province that included Afghanistan and parts of Pakistan. In this context it refers to al-Qaeda “central” (AQC) or senior leadership (AQSL) based, as we now know, in Pakistan.

[UPDATE] The fuller biography of al-Qaduli written by his son and leaked from within IS in 2018 adds detail on the early 2006 trip to Pakistan, saying (pp. 56-57) that al-Qaduli got to personally meet with Atiyya, as well as two other senior al-Qaeda members who had been with the group almost from the 1990s, soon after its creation. One was Musatafa Abu al-Yazid (Saeed al-Masri), an Egyptian military official and logistician, reportedly the overall commander of al-Qaeda’s operations in Afghanistan and a finance administrator when he was killed in a U.S. drone strike in Pakistan in May 2010. The other was Mohamed Hassan Qaid (Abu Yahya al-Libi), a Libyan scholar-warrior arrested during the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, who escaped from Baghram Airbase in July 2005 and rose to be one of al-Qaeda’s crucial day-to-day managers and possibly its overall deputy by the time he was finally struck down in June 2012.

This reference in Al-Naba is a rare admission from IS that it had facilitation networks and general freedom of operations in the Islamic Republic of Iran, ostensibly a primary foe of the group’s. Most of IS’s mentions of the Iranian dimension to their activities occurred in 2013-14 in the context of the schism with al-Qaeda, where IS contended it only left Iran alone because AQC ordered them to. “[The Islamic State] repressed its rage all these past years, enduring accusations of being collaborators with Iran, its bitterest enemy, for not having targeted it, … in compliance with the orders of al-Qaeda to protect its interests and supply lines in Iran”, said Taha Falaha (Abu Muhammad al-Adnani), the IS spokesman, in 2014. “So, let history record that Iran owes an invaluable debt to al-Qaeda.”

The phrase translated as “nom de guerre” is “isman harakiyyan”, literally “movement name”.

The revelation that al-Qaduli was Abdullah Ibn Rashid al-Baghdadi (or Abu Abdullah Rashid al-Baghdadi), the formal leader of al-Majlis Shura al-Mujahideen (MSM), strongly suggests that al-Qaduli had been selected to succeed Zarqawi and would have done so had he not been arrested in April 2006 (see footnote 13). There is an interesting related element to this concerning MSM/ISI-AQC relations.

There was a lot of dodgy reporting in May 2015, much of it traceable to the Iraqi government, claiming variously that al-Qaduli had taken over as “caretaker” leader of IS while the caliph, Ibrahim al-Badri (Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi), was injured, and that al-Qaduli had been killed. The Iraqi government’s mendacity during the anti-IS campaign was a byword for analysts, but Baghdad does have intelligence penetration of IS, and identifying al-Qaduli—albeit under the kunya Abu Alaa al-Afri, and not making the connection to Abu Ali al-Anbari—was correct. There was another detail in the Baghdad-origin reporting that had the ring of truth, namely that al-Qaduli was a favourite of Usama bin Laden’s, and Bin Laden had wanted al-Qaduli to replace Zarqawi in 2006 (and would have preferred al-Qaduli to become emir in 2010 rather than al-Badri, impossible again since al-Qaduli was still in jail). Al-Qaduli knew AQC’s leadership—he had met them in person, not merely exchanged letters with them—and AQC seems to have been impressed with al-Qaduli. The decision of Zarqawi and al-Badri to appoint al-Qaduli as the liaison with “Khorasan” indicative of this.

Whether al-Qaduli becoming ISI in emir in 2006 and 2010 would have prevented the rupture with AQC in 2013-14 is in the realm of speculation, but there are reasons for doubt. The two sides were brought together for contingent reasons at a specific moment in 2004 and almost immediately started drifting apart because of the fundamental theological-strategic differences. To put it another way, the problem for AQC in keeping ISI within the fold was not Zarqawi but Zarqawism. In turn, the fact is Zarqawi found his way to al-Qaduli so quickly after entering Iraq in the spring of 2002 because al-Qaduli already adhered to a Zarqawist form of jihadism and had done for a decade.

The revelation al-Qaduli was Rashid also solves two mysteries of the Iraqi jihad.

First, Rashid has generally been assumed to be Hamid al-Zawi, with the argument being he changed his kunya to Abu Umar al-Baghdadi on the founding of the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) in October 2006 to sound more caliphal. This was never unanimous. Initial reports suggested Rashid was “a former officer in Saddam’s army, or its elite Republican Guard, who has worked closely with al-Zarqawi since the overthrow of the Iraqi dictator in April 2003”, and some specialists always maintained that Rashid and Abu Umar/Al-Zawi were different people. Now we know conclusively the doubters were correct.

Second, while it has long been suspected that ISI’s media emir, Khalid al-Mashadani (Abu Zayd al-Mashadani), was feeding misinformation to the Americans after his capture in July 2007, the puzzle was: To what end? Now we know.

As explained in a recent study by Craig Whiteside, the young spokesman for al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia (AQM), Abu Maysara al-Iraqi, transitioned seamlessly into being MSM’s spokesman. Whiteside points out that after Abu Maysara was killed (likely in June 2006), a man named Abu Ammar al-Dulaymi gave several speeches under the title of MSM spokesman, and read a speech on 1 July 2006 attributed to Rashid. Thus, it seems IS is still playing games about this because Al-Qaduli did not personally deliver the MSM’s first official speech, as Al-Naba claims—he could not, as he had been arrested two months earlier. That al-Qaduli never spoke in an audio recording as Rashid, and Abu Ammar spoke for Rashid after al-Qaduli had been imprisoned, led the Americans away from understanding who al-Qaduli was.

Al-Mashadani allowed the American misunderstanding that Rashid was Abu Umar to stand, and then claimed that Rashid/Abu Umar was an actor named Abu Abdullah al-Naima, who read audio statements on behalf of Abd al-Munim al-Badawi (Abu Hamza al-Muhajir), Zarqawi’s Egyptian successor as head of AQM and subsequent deputy to al-Zawi. According to the U.S., the al-Naima ruse was meant to disguise the fact that ISI was just an Iraqi front for the foreign-led AQM. Two other sources claimed Abu Umar was a smokescreen for al-Badawi, both of them IS defectors: Abu Sulayman al-Utaybi, who reported in 2007 that al-Badawi had said: “A man will be found [to be ISI’s caliph] whom we will test for a month. If he is suitable, then we will keep him … If not, we will look for someone else,” and Abu Ahmad in 2014. But it wasn’t true, though the U.S. was allegedly never actually sure that Abu Umar was a real person until it killed al-Zawi in the company of al-Badawi in 2010. Now, other sources suggest the U.S. realised quite quickly that al-Mashadani was lying about Abu Umar—and chose never to share this with the public for reasons unclear—so perhaps al-Mashadani did not have so much success on the Abu Umar front.

Nonetheless, al-Mashadani’s has to be reckoned to have pulled off one of the most consequential information operations in recent times in shielding al-Qaduli: the Americans never realised who al-Qaduli was in the six years they held him, allowing al-Qaduli to be released in 2012 with fateful results.

It appears that al-Qaduli was arrested for the second time as a by-product of Operation LARCHWOOD 4, a raid in Yusufiya on 16 April 2006 intended to round up a mid-level administrative emir, Abu Atiya, who was part of an AQM/MSM cell in Abu Ghraib and ran their media efforts. Five people were killed defending Abu Atiya’s safe-house, two of them wearing explosive vests; five men (plus a number of women and children) survived. Abu Atiya was among the living and was arrested, as was “[a]n older man [who] also appeared to be an insurgent.” It now seems likely this was al-Qaduli (he would have been fifty at that time).

Thanks to the information operation by IS, the Coalition never realised it had al-Zarqawi’s deputy in custody. The raid was otherwise a success, however. The Coalition discovered a trove of information, including a plan to stoke sectarian warfare and expel the Shi’is from Sunni-majority areas. The goal is to “move the battle to the Shi’a depths and cut off the paths from them by any means necessary to put pressure on them to leave their areas,” the AQM/MSM documents said. The suggestion included an idea to “leave or reduce our operations against them in our areas [the Sunni areas] for the near future, and will perform our work against them in the areas of Baghdad itself, as well as the surrounding areas.” The haul also enabled the release of the famous tape of Zarqawi firing a machine gun, giving the Coalition a positive way to identify al-Zarqawi, and also allowing the release of the outtake where Zarqawi mishandles the weapon. The information gathered soon led to Zarqawi’s downfall: he was killed on 7 June 2006..

Among the most consistent themes of al-Qaduli’s life was a complete detestation of anything that put man’s law over God’s law—not just democracy but Islamist groups like the Muslim Brotherhood that try to change the regional states by engagement with them. The forty hours of lectures al-Qaduli leaves behind, a milestone in setting out the Islamic State’s ideological vision that will have an impact for decades to come, return to this point again and again.

Manaf al-Rawi was recruited by Ghassan al-Rawi (Abu Ubayda), a former Ba’athist officer in Saddam Husayn’s army and a key deputy to Abu Musab al-Zarqawi involved in bringing the foreign jihadists into Iraq from Syria. Manaf was the driver for Mustafa Ramadan Darwish (Abu Muhammad al-Lubnani), Zarqawi’s second deputy and the leader of the security wing of the early IS movement, including its chemical weapons program. Manaf was arrested in early 2004 and released in November 2007. Having been networked and given additional religious instruction in prison by al-Qaduli, Manaf emerged much-improved in stature and in an environment where the leadership was strained. Manaf became the wali of Baghdad, known as “the dictator”. Manaf’s most lasting impact was a wave of crippling bombings against the Iraqi government—in direct collusion with the remnants of the fallen Iraqi Ba’athist leadership and Assad—in late 2009 and early 2010 that had a profound impact on the course of events, including consolidating more power in the hands of the increasingly-sectarian Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki, which provided IS with political space to revive. Manaf was arrested on 11 March 2010, and his information was critical in the downfall of Hamid al-Zawi and Abdul Munim al-Badawi on 18 April 2010. Or so it is usually said.

The complication with the narrative of Manaf-as-turncoat is highlighted by the fact he has so often been cited in laudatory terms in IS propaganda in the years since 2010, as he is again here. And this Al-Naba article highlights another problem with the narrative: Manaf met Al-Qaduli in prison, knew full-well who he was, and never told the Americans, allowing the information operation put in place three years earlier to shield al-Qaduli to continue. At a minimum, these are not the actions of a complete sell-out. Perhaps Manaf’s intelligence was not as key to the two shaykhs’ downfall as is often supposed, and the claim otherwise results from a black propaganda campaign by the Iraqi government or the Americans or both. Or maybe Manaf was forced to give up information leading to the two shaykhs, but he managed to hold on to another secret(s) that was much more important to IS. Possibly Manaf did something in prison that was of such benefit to IS it demonstrated where his true loyalties were. We know enough to know that the conventional story of Manaf betraying IS behind the wire is not quite right; how it is wrong and/or what is missing is unknown, and could well remain so unless IS chooses to tell us.

Manaf al-Rawi was replaced as emir of Baghdad by Hudayfa al-Batawi (sometimes transliterated: Hudhayfa, Huthayfa, or Huzayfa, and al-Bittawi). Al-Batawi was arrested on 27 November 2010, a month after the Baghdad church attack that al-Batawi orchestrated. Al-Batawi was killed on 8 May 2011 during a prison mutiny.

When contact was broken between ISI and AQC and to what extent is unclear. Al-Qaduli was the known contact-point between AQM/ISI and AQC up to his arrest in April 2006, as mentioned by Al-Naba.

After al-Qaduli went to prison, Khalid al-Mashadani seems to have taken the job, before he, too, was arrested in July 2007. From the Abu Sulayman al-Utaybi episode we know—because AQC mentions it in their letter of 10 March 2008—that the man AQC believed was theirs within ISI, Abdul Munim al-Badawi (Abu Hamza al-Muhajir), had written to them around this time. Some interpret even this communication in 2008 as showing al-Badawi “slow rolling” AQC. The absence of concrete evidence of communication between al-Badawi and AQC after this is does not mean there was none, of course, but the level of communication cannot have been very great.

On 6 July 2010, a little under three months after al-Badawi was killed, Bin Ladin wrote to Jamal al-Misrati (Atiyya) directing him to “ask several sources among our brothers [in Iraq],” including “our brothers in Ansar al-Islam,” about Ibrahim al-Badri (Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi), the new ISI emir, since Bin Ladin did not know al-Badri or his deputy, Numan al-Zaydi (Abu Sulayman al-Nasser). A letter from Adam Gadahn to Bin Ladin in January 2011 said that communication between AQC and ISI had been “practically cut off for a number of years”.

There is a question whether al-Badri ever communicated with AQC on his own—which gets into the whole issue of ISI’s relationship with AQC. Al-Qaeda has publicly claimed that ISI secretly wrote to Ayman al-Zawahiri after Bin Ladin was killed in May 2011 to ask, “Do we renew the bay’a in public or in secret as it was done before?” The Islamic State denies this and said it had no such pledge of allegiance, though al-Badri personally said, in public, after al-Zawahiri’s ascension, that al-Zawahiri had “faithful men in the Islamic State of Iraq”.

Al-Qaduli resumed the liaison role between ISI and AQC after he got out of prison in 2012, but that only lasted a year before the spring 2013 blow-up over Jabhat al-Nusra that resulted in the total severing of relations in February 2014.

This piece of IS’s account makes more sense—with regard to the timing—than al-Qaeda’s claim that al-Qaduli toured Syria for six months before the announcement of ISIS.

U.S. Defence Secretary Ash Carter announced al-Qaduli had been killed on 25 March 2016. There was some early reporting that al-Qaduli had been eliminated in an airstrike, but it became clear reasonably quickly that he had been killed in an American raid into Syria the day before.

The Qurayshi in al-Qaduli’s name suggests he was in line to be caliph.

Would mean al-Qaduli was born in 1955 or early 1956, about which there had been some dispute.

Craig Whiteside suggests that the absence of Hamid al-Zawi (Abu Umar al-Baghdadi) among al-Qaduli’s “beloved martyr brothers” is not an accident and signals a rift of some kind. This is plausible. Al-Qaduli worked alongside al-Zawi, IS’s first proto-caliph and the man who oversaw the rebuilding of the organisation from 2006 onwards. Most IS operatives would strain to claim a connection to al-Zawi; to omit a genuinely important one seems calculated. Additionally, al-Qaduli is acknowledged to have been close to Abu Hamza al-Muhajir, al-Zawi’s inseparable deputy who died in the same room as him in April 2010. It is difficult to imagine al-Qaduli could be close to Abu Hamza and not have had an extensive relationship with al-Zawi, so the pointed absence of al-Zawi’s name on the honour role of al-Qaduli’s most-cherished compatriots likewise points to a deliberate decision.