The Palestinian Matrix of the Islamic Revolution in Iran

Watching the current uprising in Iran, and the savage crackdown by the Islamic Republic, it is impossible not to notice the muted reaction of those who have, for two years, been so vociferous in condemning Israel’s defensive operation in Gaza after the Iran/HAMAS pogrom. The contrast can seem like a contradiction only if the “human rights” rhetoric of the activists is taken seriously. There was never any reason to.

The first “pro-Palestinian” demonstrations around the world in the hours and days after 7 October 2023, reflecting the euphoria among Palestinians and in Islamdom more broadly, were open celebrations of the rape and slaughter carried out in Israel by the Gaza-based units of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC): sweets were handed out and chants of “gas the Jews” were heard as far away as Australia. The only political demand from the protesters, made as Israel was trying to pick up and identify the charred body parts of her citizens, was that HAMAS be left alone to prepare the next massacre of Israelis it had promised. The demand remained the same after the street activists and the powerful international disinformation ecosystem they are attached to switched from a triumphalist to a plaintive tone amid the IRGC jihadists’ waning fortunes on the battlefield in Gaza.1

The leaders of the “pro-Palestinian” movement denouncing the Iranian protesters as “Zionist” stooges, and “Palestinians say[ing] they hope the [Iranian] regime stays in place and protests die down soon”, are being entirely consistent. They were with the Islamic Revolution when it rampaged through the Israeli kibbutzim and they are with the Islamic Revolution now its central node is challenged. This did not begin in 2023. Palestinians and supporters of the Palestine Cause were integrally connected to the Islamic Revolution long before it swept to power in Iran in 1979.

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini had first attempted revolution in Iran in June 1963 in response to the modernising “White Revolution” of the Shah, Muhammad Reza Pahlavi, specifically the proposal to provide education to girls. Khomeini was swiftly defeated thanks to the decisiveness of Prime Minister Asadollah Alam.2 Undeterred, Khomeini tried to start trouble again after he was released from house arrest, so the Shah had him expelled in November 1964, initially to Turkey, before Khomeini settled in Iraq in September 1965, where he stayed until his move to Paris in October 1978. Khomeini, taking the lesson that he could not succeed on his own, set about building a coalition capable of toppling the Shah.3 The Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) was one of the pivotal allies Khomeini recruited, and Palestinians formed the broader matrix that linked the forces ranged against the Shah, which he correctly identified as an “unholy alliance of the Red and Black”, of Leftists and Islamists.

The Mojahedeen-e-Khalq (MEK), an Islamist-Marxist group that is by now a sinister cult, was the inaugural inductee to Khomeini’s cause, functioning as the terrorist wing of the Imam’s Revolution. MEK was officially founded in late 1965 by a circle of students, beneficiaries of the Shah increasing university access.4 After developing its ideology and expanding its activities and membership for two-and-a-half years, MEK was restructured to prepare for a violent seizure of power in the spring of 1968,5 and turned to the PLO for help.

The PLO, grouping together the fedayeen terrorists used by the Arab States in their war against Israel, was created in 1964 as an instrument of political warfare. In the wake of the 1967 Six-Day War, the PLO had been transformed. By 1969, the PLO was a vehicle for one of the fedayeen groups, FATAH led by Yasser Arafat, albeit the PLO was still formally an umbrella organisation and certain other of the emerging Palestinian factions—notably the Communist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP)—retained autonomy and some influence within PLO structures.

The PLO was always a practitioner of coalitional politics, willing to give and receive support from any actor that could help its cause. Most importantly, the PFLP’s terrorism division came under direct KGB control in 1972, and the broader PLO was in the Soviet orbit by this point. MEK’s point of contact with the PLO, Ali Hassan Salameh (Abu Hassan), a key Arafat lieutenant, even worked the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).6 Salameh was in charge of Arafat’s Praetorians, out of which evolved the PLO’s special Force 17 in the early 1970s, a unit with an important part in the Iranian Revolutionary drama, and he was an architect of the “deniable” Black September front the PLO used to carry out its worst atrocities, most infamously the horrific torture and murder of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics in 1972.7

Deeply impressed by the PLO’s pioneering international terrorism, hijacking airplanes and murdering Jews around the globe, MEK made its initial outreach to the PLO in the autumn of 1969, and met with PLO representatives in Qatar and Dubai in March 1970. At a second set of meetings weeks later in Amman and Beirut, MEK got to meet—and were vetted by—Salameh. MEK passed ideological muster, its antizionism judged sincere and its “anti-colonialism” properly formulated so as not to oppose Soviet imperialism. Moreover, MEK was recognised as a useful tool against the Shah, despised by Palestinians for being Israel’s closest and most powerful Muslim ally. Salameh signed-off on developing relations.8 MEK sent its first detachment to the PLO terrorist training camps in Lebanon and Jordan in July 1970, and many more would follow.9 Members of MEK’s “Central Cadre” were present in the camps when the PLO launched its revolt against the Jordanian monarchy in September 1970; they would claim the experience considerably improved MEK’s military proficiency.10 MEK’s operatives were deported with the defeated PLO to Lebanon.11

In late August 1971, shortly before MEK planned its inaugural terrorist atrocity, the majority of its leadership was arrested. Though the Shah had survived two assassination attempts by the religious opposition, in 1949 and 1965, he was by this time less concerned about the Islamists, partly because of Alam’s reassurances that he had, during the 15 Khordad events, “crushed them once and for all”.12 It was a self-deception that benefited Alam at Court and the Shah wanted to believe it. Had MEK remained an insular organisation, its plans to sabotage the celebration of 2,500 years of Monarchy in Iran might well have succeeded, but immersion in the PLO milieu meant, almost by definition, contact with Eastern Bloc intelligence officers and the Soviet Communist apparatus.13 It was moving in such close proximity to the KGB that led to MEK’s detection.

The Soviets reportedly brought some of the Mojahedeen for terrorist training in the Eastern Bloc. Moscow Centre certainly did facilitate MEK in reaching the PFLP camps in Lebanon, Syria, South Yemen, and Libya under Muammar al-Qaddafi. Qaddafi, a natural ally, embodying as he did a fusion of Islamism and Communism,14 also provided significant amounts of money to MEK and helped with the logistics of their transfer back into Iran.15 While Libya was not literally a Soviet colony in the same way as South Yemen, the only fully Marxist Arab State established during the Cold War, Colonel Qaddafi’s role as a reliable cut-out for Moscow makes this a distinction without much difference.

Soviet influence was apparent in Libya within a year of Qaddafi’s September 1969 coup, and by the end of the 1970s the CIA, which wilfully underplayed the Soviet role in international terrorism because of its policy preferences,16 conceded that—despite allegedly “incompatible ideologies”—Qaddafi’s Libya and the Soviets were consistently united on the “immediate course of action”, specifically training, arming, and funding radical groups throughout the Middle East, Palestinians most notably, and supporting South Yemen. The result, said the Agency, was that “on a practical level, the Libyans have acted for the Soviets in the Third World in a manner similar to that of the Cubans”,17 the most important non-European Soviet colony, administered by Fidel Castro, the Communist bridgehead in Latin America and spear-tip of Revolution as far away as Africa. It was as near as the CIA could bring itself to admitting Qaddafi’s Libya acted as a Soviet Satellite State in the Cold War.18

The large Soviet role in international terrorism was obvious in real time to anybody who wanted to notice,19 but Moscow regarded it as one of its most closely-guarded secrets, and took steps to publicly distance itself from its terrorist assets, namely by dealing with them at one step remove, through its KGB clone services in the Captive Nations. This paper-thin veneer was remarkably successful in getting most Western public intellectuals and even the CIA to generally treat the idea Moscow was behind groups like Baader-Meinhof in Germany, the Italian Red Brigades, and the Japanese Red Army as a conspiracy theory.20 Naturally, therefore, in a case like MEK—where Moscow was interfacing with terrorists through other (Palestinian) terrorists that were handled by, say, the East German Stasi and Qaddafi—the Soviets had further deniability and immunity from consequences.21 In the West, anyway.

The Shah, a firm sentry in the Cold War even when the West’s nerve faltered in the détente era, was not deceived by the Soviets and ensured SAVAK, the small but effective secret police, never lost sight of the Communist menace.22 The Soviet attempt to assassinate the Shah in 1962, at a time when the KGB had largely ceased assassinations abroad, is a measure of the difficulties the Shah caused Moscow.23 By the late 1970s, thanks to the ingenuity and diligence of SAVAK,24 the Legal Soviet apparat in Iran was virtually paralysed.25 The Soviet-run Tudeh (Communist) Party was widely infiltrated by SAVAK,26 and MEK, unfortunately for them, approached one such spy trying to acquire dynamite in the summer of 1971.27 After interrogating the MEK leaders, SAVAK rolled up the wider network. Those picked up in the dragnet against whom there was insufficient evidence were released, and SAVAK thwarted a MEK attempt to kidnap the Shah’s nephew, intending to trade him for their imprisoned comrades. In total, nearly seventy MEK conspirators were imprisoned for subversion, contacting foreign agents (the PLO), and terrorism, among other things, and in May 1972 five senior MEK terrorists were executed.28

It was at about this point in 1972 that Khomeini established a tactical alliance with MEK, declaring that it was “the duty of all good Muslims to support [MEK] and overthrow the Shah.” Khomeini gained the ability to reach inside Iran and MEK gained legitimacy with Shi’a Islamists, some of whom were perturbed by the Leftist dimension to their ideology and spiritual leader Ayatollah Mahmoud Taleghani (known as “the Red Mullah”), increasing MEK’s ability to recruit as it set about rebuilding.29 It was the first bridge between Palestinian militancy and Khomeinist Islamism, the backbone of the Revolution to come.

When the Shah spoke of his enemies in the 1978-79 Revolution as an “unholy alliance of the Red and the Black”, of Communists and Islamists, he was not engaged in propaganda. From the spring of 1972, if not earlier, the Shah was aware of the PLO “training Iranian terrorists”,30 and learned of the “lunatic” Qaddafi funding these elements shortly afterwards.31 The secret intelligence the Shah had proving this, and the discovery of Libyan and Palestinian documents on the murderers inside Iran,32 were hardly necessary. That “armed actions inside Iran” by terrorist-revolutionaries took place under “the direct influence of the armed Palestinian struggle” was so blatant that it was being reported publicly in the Arab world by the end of 1971. Everyone in Lebanon, and anybody else who could read Arabic newspapers, knew the PLO was providing “practical training in the use of arms” to anti-Shah Iranian terrorists, and then helping these people return to Iran where they could “train other members” of their groups,33 a train-the-trainers system that reached thousands by 1978.

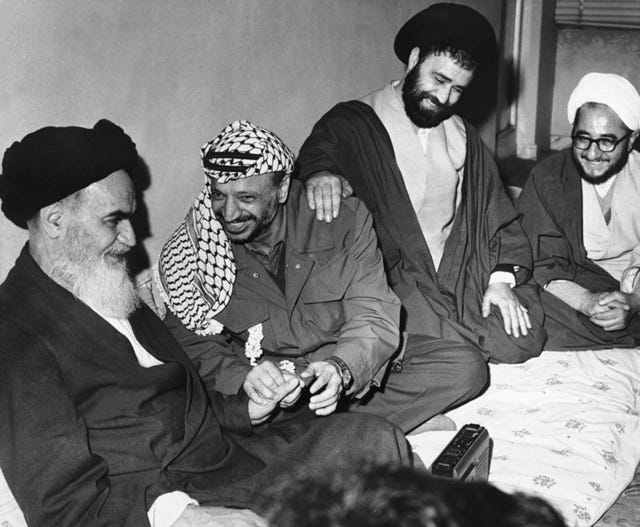

A year after Khomeini engaged the Palestinian milieu via his compact with MEK, in 1973, Khomeini forged a direct relationship with the PLO. The Imam would develop a personal relationship with Arafat in time,34 and Arafat even offered to provide personal sanctuary when Khomeini had to leave Iraq in 1978,35 but at this stage it was Khomeini’s trusted aide, Ali Akbar Mohtashamipur, who went to Beirut to work out the details with Arafat. The benefits were mutual: Arafat saw the chance to increase his stature in the Muslim world and beyond by association with the struggle in the region’s keystone State, and Khomeini could independently build up the nucleus of his own army—on Israel’s doorstep.36

The eradication of the Jewish State, a goal shared with the PLO, was not, to Khomeini, an extraneous task but a core part of the transnational vision that motivated his desire to capture Iran. When Arafat was received in Iran as the first visiting “Head of State” days after Khomeini’s total triumph in February 1979, the Imam declared that the priority once the Islamic Revolution was consolidated was to “turn to the issue of victory over Israel”.37 It has been well-said that “Khomeini’s system … can best be understood as a Soviet Union in Islamic garb”,38 and the Islamic Republic intelligence-security apparatus was visibly modelled on the Soviet KGB.39 Like Lenin before him,40 Khomeini had no concern for his “own” country per se. On the plane back to Iran in February 1979, after fourteen-plus years in exile, Khomeini was asked what it meant to him and famously answered, “Hichi” (“Nothing”). Iran was to Khomeini, as Russia was to Lenin, merely a useful launchpad for worldwide Revolution.

The Khomeinist cadres trained in intelligence and terrorism at the PLO camps in Lebanon in the 1970s became the core of the IRGC.41 On its own, this Palestinian contribution would be of unexaggeratable importance, providing to the Islamic Revolution the capacity to form the key institution that has sustained it and exported its malady in the region for nearly half-a-century. But the PLO role in the concept and creation of the IRGC seems to have been even more direct.42 The Palestinian-trained Khomeinists were a large enough coterie that they were also the basis of the other Islamic Republic security-intelligence institutions.43

The PLO-trained Khomeinists who went to Iran during and after the Revolution were officially flagged as Pasdaran.44 Others remained in Lebanon and adopted the label Hizballah (Party of God),45 becoming the first of the IRGC’s “external armies”. A lot of the stay-behind IRGC cadres in Lebanon had Lebanese citizenship because wherever Khomeinism is planted,46 again like the Soviets, it acts like a virulent cancer, replicating itself and consuming the host. Khomeini briefly continued using the PLO to train the IRGC inside Iran,47 but, even had Arafat not so quickly exhausted the Imam’s patience,48 the Khomeinist infrastructure had outgrown PLO tutelage before 1978 and begun to annex swathes of the PLO, notably from Force 17, whose bases were used to train the first batches of militants Khomeini sent to Arafat.49 By 1982, the PLO was broken in Lebanon and Hizballah filled the void. Within a few years, the IRGC, significantly aided by its entrenched Lebanese base, was peeling away chunks of the PLO in the Palestinian Territories and ultimately usurped the Palestine Cause entirely through its HAMAS unit. (The same dynamic played out with MEK, which realised only too late the liability of it increasing closeness to the Khomeinist apparatus after 1975.50 MEK, crippled by the defection of over-half its “most loyal” armed cadres to the IRGC in the spring of 1979, could not hold off when the Imam came for them in 1981.51)

Of note, it was a Force 17 veteran, Imad Mughniyeh, a fully commissioned IRGC officer,52 who served as the military chief of Hizballah until he was killed by MOSSAD and the CIA in 2008. Mughniyeh was, before Usama bin Laden, the most deadly anti-Western terrorist. Bin Laden, indeed, was inspired by the Marine barracks bombing that Mughniyeh operationally led, and it was with Clerical Iran’s assistance, starting in the early 1990s under a pact signed personally between Bin Laden and Mughniyeh, that Al-Qaeda became a truly global organisation capable of 9/11.

The other major pool of recruits to IRGC/Hizballah in Lebanon came from the Amal Movement, the militia formed in 1974 to protect Lebanese Shi’is from the bullying of the PLO, which had created a State-within-a-State in the Shi’a-majority south of Lebanon after the expulsion from Jordan. By the spring of 1975, the PLO had plunged a second country into civil war and this time there was no Hashemite monarch (with Israeli support) to terminate the chaos swiftly. Amal’s leader, Musa al-Sadr, an Iranian-born cleric, was a most improbable warlord. Al-Sadr, in theory a traditionalist opposed to Khomeini’s version of Shi’ism, blurred the lines amid the radicalism of the moment, becoming a hectoring critic of the Shah, and deputised Mostafa Chamran, a PLO-trained Iranian anti-Shah émigré, to lead the military effort.53 The immediate-run effect of this was to anger the Shah, heretofore Al-Sadr’s patron, cutting off an important source of support at a highly inopportune moment,54 and in due course there would be a shattering exodus from Amal to the PLO-aligned Khomeinists under a protégé of Chamran’s, Husayn al-Musawi.55

The disappearance of Musa al-Sadr and two companions in Tripoli, Libya, on 31 August 1978, put on display the external support system—the tripartite alliance of Khomeini, Arafat, and Qaddafi, with the Soviet Union hovering in the background—that drove the Islamic Revolution in Iran.56 Eliminating Al-Sadr was important in paving the way for Amal’s fragmentation, but this local impact in Lebanon was secondary. The conspiracy against Al-Sadr was driven by those who were using Lebanon as a launchpad for the Islamic Revolution, which was entering its crucial phase in Iran.

In the summer of 1978, as the simmering turmoil in Iran visibly became a Revolution, the Shah was working to patch things up with Al-Sadr. By giving support to Al-Sadr, the Shah could potentially smother the nerve-centre of the Revolution against him in Lebanon, and if Al-Sadr ceased to play footsie with the Shi’a radicals advocating clerical government and publicly blessed the Shah’s government, it might impede the ideological drift of Iranians into Khomeini’s camp. Al-Sadr understood that Khomeini prevailing in Iran would reverberate in Lebanon and endanger his political position.57 What Al-Sadr did not understand was the personal danger he was in. When Khomeini asked for Al-Sadr to meet in Libya with Ayatollah Muhammad Beheshti, Khomeini’s indispensable agent coordinating the Islamic Revolution on-the-ground in Iran, to try to find a compact, Al-Sadr did not sense a trap. To Al-Sadr, it was a chance to explore his options, and the venue seemed perfectly safe.

Al-Sadr was personally friendly with Colonel Qaddafi, who had provided funds to Al-Sadr’s Amal, and in any case it seemed inconceivable to Al-Sadr a Muslim ruler could harm a high-profile cleric.58 Al-Sadr was unaware of the depth of Qaddafi’s anger that Amal continued clashing with the Palestinians and refused to fight Israel,59 the enemy against whom Al-Sadr had said in public the weapons of his militia—many bought with Libyan money—were directed.60 This made it easier for Beheshti to convince Qaddafi that Al-Sadr was a Western agent, though, in pressing Qaddafi to liquidate Al-Sadr, Beheshti was quite explicit that it should be done because Al-Sadr “was a threat to Khomeini”. Qaddafi clearly found this a persuasive argument and Beheshti telephoned Qaddafi on the day Al-Sadr vanished to impress upon him that Al-Sadr must not leave Libya.61 That Salameh, Arafat’s liaison to the CIA, was immediately able to tell the Agency station chief in Beirut about these events speaks to the PLO’s complicity.62 Arafat had certainly communicated to Qaddafi that the Palestinian Cause would benefit if Al-Sadr went away.63

The architects of Al-Sadr’s removal from the board got what they wanted. The Lebanese epicentre of the Islamic Revolution became easier to navigate for those hellbent on bringing down the Shah. Qaddafi’s stature was already high in a situation where any illusions of Lebanese State authority had been obliterated and militias on all sides wanted access to Libyan largesse.64 Now Qaddafi and his allies had the aura of winners, diminishing the will to stand against them. Qaddafi was able to deliver vast sums of cash to Khomeini’s agents and MEK operatives at the PFLP and other Palestinian camps through the Libyan Embassy in Beirut. Qaddafi’s money allowed Khomeini to suborn clergy inside Iran, who otherwise would have sided with Grand Ayatollah Kazem Shariatmadari in opposing Khomeini’s velayat-e-faqih concept, and bought MEK further weapons for an arsenal already called “impressive” by the CIA in September 1977, as well as sophisticated communications equipment. The Palestinian military and intelligence training, derived from the Soviets, enabled MEK to infiltrate the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and even the motor pool used by U.S. army advisers to the Shah’s military.65 As the end drew near in late 1978, the PLO openly revelled in the accusation it was “fomenting trouble in Iran”,66 and an undisguised flood of Soviet-aligned Palestinians from Lebanon joined the Palestinian-trained terrorists inside Iran.67

The coalitional aspect to the anti-Shah campaign shows up in the non-military dimensions. For instance, Qaddafi and Arafat assisted on the propaganda side, maintaining relations with the circle in and around the “moderate” Islamists of the Liberation Movement of Iran (LMI), who carefully shielded Khomeini in Paris from revealing his true intentions.68 (The LMI played a similar role inside Iran, obfuscating Khomeini’s program to the Iranian middle class and religious “modernists”.) As on the terrorism side, this was not really hidden. A Libyan emissary and the PLO “foreign minister” overtly met Khomeini in Paris in late 1978,69 and soon after the Shah’s departure in January 1979 the chief spokesman of the PFLP boasted publicly that his group had assisted “the Iranian people’s struggle for the past seven years” with “everything from propaganda to the use of weapons”.70

The same Palestinian matrix, embedded in the broader Soviet infrastructure, was, unsurprisingly, in evidence with the Red wing of the Revolution, represented primarily by Sazman Cherikha-ye Fedayeen-e-Khalq (The Organisation of Iranian People’s Self-Sacrificing Guerrillas), known as the Fedayeen in Iran and called “Chariks” by the Americans.71 The Fedayeen attack on the police at Siahkal, on 8 February 1971, began the terrorism wave that plagued the Shah’s Iran through the 1970s, and the Fedayeen was the most active terrorist group. While often described as leaning Maoist, the Fedayeen owed the bulk of its structure and ideology to the Soviet Union,72 and publicly admitting to receiving support from South Yemen and the PFLP. Even the CIA, which performed catastrophically throughout the Iran crisis, understood that the money and other resources delivered through South Yemen came from the Soviet Union.73

The Fedayeen, like MEK, had access to the Palestinian camps of the Soviet proxy PFLP in Libya and received money from Qaddafi. Fedayeen sojourns in Lebanon connected them to the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and Baader-Meinhof Gang, among others. And the Soviets—not-quite-directly, via Czechoslovakia, East Germany, and Poland—provided weapons on a large scale to the Fedayeen.74 This obviously enabled the Fedayeen terrorism campaign, and the psychological-political impact was immense: eroding confidence in the Shah’s government, emboldening its opponents, and creating a novel security situation decision-makers struggled to adapt to.75 The prestige of the Fedayeen was burnished further by its participation in foreign conflicts—supporting the Palestinians in Lebanon and the Communist Revolution in Oman, which the Shah took responsibility for crushing after the British pulled out East of Suez. The Fedayeen’s tactical alterations around 1976 enabled it to put down roots among the lower classes, setting it on a footing to play a meaningful political role in the Revolution, while continuing its essential military role. The Fedayeen was a leading element in the violent coup against the Interim Government of Shapur Bakhtiar on 9-11 February 1979 that brought Khomeini to power.76

Khomeini officially shunned Communists and never personally established contact with the Fedayeen. But he had no need. The Imam could keep his hands ideologically clean and benefit operationally from the Communist capacity for popular mobilisation and violence via MEK. By mid-1977, the Fedayeen and Mojahedeen “had agreed to form a united front and share resources”,77 an arrangement doubtless smoothed by the Soviet and Palestinian connective tissue that already bound them in a common program.

It was at almost this exact moment in 1977 that the Shah began his political liberalisation, intending to hold elections to refashion Iran from an executive Monarchy to a constitutional one by the end of 1979.78 The coordination of the two main terrorist groups meant they were able to more effectively test whether the announced changes were for real, and to find that they were.79 It was the Shah’s terrible misfortune that almost the only people to believe he wanted to reduce his own power were those who saw this as an opportunity to impose totalitarianism.80

Post has been updated

FOOTNOTES

A caveat: while outright jubilation faded from the “pro-Palestine” presentation in the months after 7 October, the actual content was quite continuous. The word “genocide”, for example, was used pre-emptively to describe the impending Israeli response—long before the process of denuding that word of meaning was completed by the United Nations.

Asadollah Alam generally did not hold positions in the formal government, but served in the Court as the Shah’s most loyal and effective adviser. For this reason, however, Alam’s one brief tenure as Prime Minister (from July 1962 to March 1964) was somewhat exceptional, vesting an unusual amount of power in the office. Which proved fortunate. In 1963, Alam did what no other Prime Minister could have in securing temporary control over the army on the eve of Khomeini’s uprising. Alam ordered the Iranian military to arrest Khomeini and prevent revolution, with force if necessary. “I had to”, Alam later confided to British ambassador Anthony Parsons. “His Majesty is very soft-hearted and does not like bloodshed.” In the event, Alam’s decisive action ensured there was little bloodshed: the insurrection was swiftly suppressed with just thirty-two people killed, according to the current regime’s Martyr’s Foundation, and that figure includes security force fatalities.

The Shah was asked in exile why he had not gone “all out against Khomeini” and answered quite truthfully: “I wasn’t this man. If you wanted someone to kill people you had to find somebody else.” When the interviewer pressed about 1963, the Shah corrected him: “It was Alam who gave the orders.” So many of the counterfactuals about Iran in 1978-79 dissolve on inspection because they fail to deal with the Shah as he actually was and rely on the myth-image of a merciless tyrant painted by the revolutionaries. A real what-if is Alam not dying in April 1978 (from the same cancer that killed the Shah, incidentally). Alam had an earthy understanding of the country many in the elite lacked, he was able to speak to the Shah frankly, and he had the unique will and ability to take independent action for the sake of the Monarchy. If Alam was at the Shah’s side when the scale of the crisis was realised in the summer of 1978, the outcome might have been very different.

See: Andrew Scott Cooper (2016), The Fall of Heaven: The Pahlavis and the Final Days of Imperial Iran, pp. 111-116, 498.

For the casualties, see this write-up of Emad al-Din Baghi’s Martyrs Foundation study: Cyrus Kadivar (2003, Aug. 8), ‘A Question of Numbers’, Rouzegar-Now. Available here.

In exile, Khomeini refined his ideas for a post-Shah Iran, giving a series of lectures in Najaf in February 1970, compiled into a book, Islamic Government, later that year. The book, in print and audio format, would circulate inside the Shah’s Iran thereafter. The CIA finally discovered the volume in 1978—and dismissed it as a probable provocation by Khomeini’s enemies (Israel was a popular suspect). The State Department thought similarly. The CIA never even had the book translated until March 1979, a month the Imam and his Revolution had prevailed, when it was too late to do anything about it.

Ervand Abrahamian (1989), Radical Islam: The Iranian Mojahedin, pp. 87-89.

Abrahamian, Radical Islam, pp. 126-127.

The CIA thought it had recruited Salameh around 1973, after cultivating him since December 1969. The Agency knew that Arafat was aware of Salameh’s contact with them, and that Salameh was in effect acting as a political channel to the PLO, but Langley believed it had Salameh’s ultimate loyalty, which it did not. Salameh was Arafat’s emissary, and used the trust he had from the CIA to shape U.S. perceptions of the PLO, with important ramifications for U.S. policy in the long-term. For the most detailed account of this, see: Kai Bird (2014), The Good Spy: The Life and Death of Robert Ames.

Salameh, understood by Israel to be Arafat’s favourite and having publicly boasted of his role in Black September, was a marked man from the moment of the Munich massacre in September 1972. It took some time for Operation WRATH OF GOD to catch up with Salameh, though, and MOSSAD made its most egregious mistake in that campaign—shooting dead the Moroccan waiter Ahmed Bouchikhi in Lillehammer, Norway, in July 1973—as part of the hunt for Salameh.

It was as MOSSAD closed the net on Salameh in the summer of 1978 that Israel discovered the depth of the CIA’s relationship with Salameh (codenamed MJTRUST/2). The Agency had given Salameh carte blanche so long as he avoided harming American interests or acting on American soil. After the PLO pushed Lebanon into civil war, Salameh’s men guarded the U.S. Embassy. In January 1977, Salameh was brought to the U.S. for a holiday, honeymooning in Hawaii and visiting Disneyland. The CIA passed on any intelligence it had about Israeli threats to Salameh and even supplied him with encrypted communications equipment to increase his security. At one point, the Agency considered giving Salameh an armoured car for the same reason. Israel viewed America’s conduct, not unreasonably, as outright treachery.

While there was some debate within MOSSAD about the extent of Salameh’s responsibility for Munich, the majority believed Salameh had to die to settle that account. By 1978, Salameh’s Force 17 was a terrorist threat in its own right, and MOSSAD officers working the Lebanon file favoured eliminating him on those grounds. What united Israel’s decision-makers and sealed Salameh’s fate was the CIA connection: “cutting this channel was very important, to show that no one was immune—and also to give the Americans a hint that this was no way to behave toward friends”, as one MOSSAD officer put it. Salameh was blown up in his car in Beirut as he drove to the Force 17 headquarters on 22 January 1979, less than a week after the Shah departed Iran and just about three weeks before Khomeini’s coup against the Interim Government.

The CIA, bewildered as ever, had the station chief in Beirut write an emotional letter of condolences to Salameh’s son, and then tried to forge relations with Salameh’s replacement, Hani al-Hassan, the main planner of the Munich massacre and a KGB asset.

See: Ronen Bergman (2018), Rise and Kill First: The Secret History of Israel’s Targeted Assassinations, pp. 177-179, 215-224.

Seyed Ali Alavi (2019), Iran and Palestine: Past, Present, Future, chapter one.

Abrahamian, Radical Islam, p. 127.

Gholam Reza Afkhami (2009), The Life and Times of the Shah, p. 398.

Alavi, Iran and Palestine, chapter one.

Abbas Milani (2011), The Shah, p. 375.

CIA Intelligence Assessment, ‘Iran: The Mujahedin’, August 1981. Available here.

Claire Sterling (1981), The Terror Network: The Secret War of International Terrorism, p. 250.

Cooper, The Fall of Heaven, p. 251.

In theory, of course, the CIA is an intelligence-gathering outfit that does not have policy preferences, let alone policy preferences it tries to forward by manipulating the intelligence it shows to the U.S. political leadership. But theory and practice are so often very different things.

CIA Intelligence Assessment, ‘The USSR and Libya: Collusion in the Middle East and Africa’, January 1979. Available here.

Ronald Bruce St John, ‘The Soviet Penetration of Libya’, The World Today, April 1982. Available here. See also: John K. Cooley, ‘The Libyan Menace’, Foreign Policy, Spring 1981. Available here.

For example: Brian Crozier wrote a chapter, ‘Soviet Support for International Terrorism’, in the 1981 book, International Terrorism, which was developed from a paper of the same name Crozier had presented at the Jerusalem Conference on International Terrorism in 1979.

The 1981 book, The Terror Network: The Secret War of International Terrorism, by Claire Sterling, caused quite a stir at the CIA by compiling vast evidence of a Soviet global terrorist infrastructure. The CIA Director was disturbed that the book, using open sources, had so much more information than the Agency seemed to have, and the obvious if unspoken explanation for this was that the CIA had simply refused to collect intelligence that contradicted an in-house theory born of political preferences the CIA is not supposed to have. (This problem would continue long into the future.) A CIA review was commissioned that acknowledged “the Soviets are deeply engaged in support of revolutionary violence worldwide” and there was “conclusive evidence” Moscow supported terrorists and the so-called national liberation movements. But, rather than accept that external critics had exposed shoddy work at the CIA, many CIA officials claimed—internally and to the press—that the review resulted from the Agency being put under political pressure from the administration, and this narrative became popularly accepted (another familiar theme).

The amazing thing is that the narrative survived the opening of the Soviet archives. Books into the 1990s and beyond continue to dismiss CIA contemporary findings of Soviet support for international terrorism as basically political propaganda from the Reagan administration, and such works could readily find “sources” for this thesis in the former CIA officials who had opposed noticing the facts now exposed in the KGB documents in real-time. A prominent case in point is Melvin Goodman, head of CIA’s Office of Soviet Affairs from 1976 to 1987. Goodman’s views can be seen at some length in the 2004 BBC documentary, The Power of Nightmares: The Rise of the Politics of Fear, by Adam Curtis, which is notably less overtly tinged with antisemitism than the BBC Panorama program from a year earlier, The War Party, but pushes the same demented idea that “neoconservatives” not jihadists were primarily responsible for the 9/11 Wars.

On the press behaviour in the Cold War, see, for example: Richard Halloran, ‘Proof of Soviet-Aided Terror is Scarce’, The New York Times, 9 February 1981. Available here. And: Leslie Gelb, ‘Soviet-Terror Ties Called Outdated’, The New York Times, 18 October 1981. Available here. The bias against acknowledging the Soviet role in international terrorism was so extreme that even in the last few years of the Cold War there were cases of major Western media outlets suppressing reports from their own journalists who had discovered the KGB’s connection to various terrorist groups. See: ‘The C.I.A.’s Master Plan’, The Nation, 17/24 August 1985. Available here.

The situation was similar with the Soviet funding and control of Communist Parties around the world, and their use of them for espionage. Moscow regarded this as a State secret of the first order, and many Western journalists and academics played along, treating the phrase “Moscow gold” as a laugh line until the end of the Cold War, when the KGB archives were opened and it turned out the “McCarthyist” accusation that the Communist Parties were consciously treasonous was wholly true. See: Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin (1999), The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB, p. 63.

A key part of what Qaddafi’s Libya did was acting as a deniable conduit for Soviet weapons, or providing money to groups who then purchased Soviet weapons. The Soviet Union not only escaped blowback for any actions these terrorists took. By avoiding being publicly identified with one actor, Moscow was able to play all sides to a conflict, as it still does. See: CIA Intelligence Assessment, ‘The USSR and Libya: Collusion in the Middle East and Africa’, January 1979.

The word “SAVAK”, on its own, became an accusation against the Shah in 1978. The opposition would claim SAVAK had 20,000 officers and millions more agents, imposing a suffocating surveillance on Iran akin what the KGB did in the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, it was said, there were up to 100,000 political prisoners, and SAVAK routinely tortured and murdered thousands of detainees.

The reality was that SAVAK never had more than 5,000 employees, could monitor no more than fifty telephone conversations at any one time, and had 10,000 names on file as full- or part-time informants, though even that number was artificially inflated as the names of individuals who were approached and refused cooperation were kept on the books. The “political” prisoner population, which included terrorists, peaked at 3,700 in 1975 and thereafter hovered around 3,000. At most 400 oppositionists were killed in clashes with security forces in the pre-Revolution terrorism wave, from 1971 to 1978. A handful of Iranians died in custody in that period, which is not the same them being murdered.

Abbas Milani, a sometime political prisoner under the Shah, concluded that there was one single case of extrajudicial murder during the Shah’s thirty-seven-year reign, when SAVAK shot nine men (most of them Fedayeen) in retaliation for a Fedayeen bombing in 1975, and “there is no evidence that the Shah knew about or ordered the killing”. There was an issue with abuse of detainees: it ceased by November 1976, after it had been brought to the Shah’s attention and the Red Cross had been given free rein in the prisons.

The situation was summed up well by Martin Woollacott, hardly an apologist for the Shah, a British journalist at The Guardian, who looked into the opposition claims about SAVAK in the mid-1970s and quickly discovered they were nonsense. “SAVAK worked very well in instilling passivity, some fear, and a large degree of acquiescence with a minimum of violence”, said Woollacott. “But the picture of SAVAK as bloodthirsty did not stand up to scrutiny.”

See: Cooper, The Fall of Heaven, pp. 237-239; and, Milani, The Shah, p. 313.

Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin (2005), The World Was Going Our Way: The KGB and the Battle for the Third World, p. 173.

Milani, The Shah, pp. 363-364.

Andrew and Mitrokhin, The World Was Going Our Way, p. 180.

Maziar Behrooz (1999), Rebels with a Cause: The Failure of the Left in Iran, pp. 38-39

Tudeh, the Communist actor in Iran that attracted the most attention, from the Shah and the West, was in many ways the dog that did not bark in the night in 1978-79. Like all “fraternal” Parties, Tudeh was entirely controlled from Moscow (CIA Review, ‘The Tudeh Party: Vehicle of Communism in Iran’, 18 July 1949. Available here). KGB management and the safe haven in the Soviet Empire, specifically the “German Democratic Republic” (GDR or DDR), kept Tudeh alive, but the Party managed little more than that.

The Tudeh was legally banned in Iran in 1949, enduringly degraded after the 1953 counter-coup, and its underground apparatus thereafter, as mentioned, heavily surveilled by SAVAK. Ideologically, Tudeh, of course, conformed to the Soviet “anti-Zionist” campaign—and still does. But Tudeh had little practical interaction with the Palestinians, beyond propaganda casting their war against Israel as part of the same “anti-imperialist” struggle as the Iranian Revolution.

Tudeh was able to find space in the summer of 1978 to produce leaflets with assistance from the Soviet rezidentura in the Embassy and KGB officers posing as TASS journalists (Andrew and Mitrokhin, The World Was Going Our Way, p. 181). As the Islamists took a tactical step back in late September 1978, Tudeh abetted the strikes that threatened the oil industry, banking sector, and the wider economy (Cooper, The Fall of Heaven, p. 420). Overall, though, SAVAK contained Tudeh effectively, denying it much of a social base, and the Party “had little, if any, meaningful impact on the Revolution” (Behrooz, Rebels with a Cause, p. 124).

Abrahamian, Radical Islam, p. 128.

Abrahamian, Radical Islam, pp. 128-129.

Cooper, The Fall of Heaven, pp. 250-251.

Asadollah Alam (1991), The Shah and I: The Confidential Diary of Iran’s Royal Court, 1968-77, p. 215.

Alam, The Shah and I, p. 504.

The Shah was asked about Qaddafi in a television interview, with Mike Wallace of 60 Minutes (broadcast on 25 October 1976), and replied simply and bluntly: “he’s crazy”.

Alam, The Shah and I, p. 498.

Quotes from Al-Ahad (Lebanon), 19 December 1971, cited in: Claire Sterling (1981, Jan. 23), ‘Who Were Those “Student” Terrorists?’, The Washington Post. Available here.

James Buchan (2012), Days of God: The Revolution in Iran and Its Consequences, p. 146.

It has to be said that Khomeini’s entourage was non-plussed by Arafat’s offer to host the Imam in the Bekaa Valley, remarking, “The Palestinians can’t even protect themselves”, and Khomeini was savvy enough to understand Paris was a much more suitable stage for the kind of political warfare he needed to wage to destroy the Shah, but it is nonetheless telling that the option was there. See: Buchan, Days of God, p. 173.

Bergman, Rise and Kill First, pp. 368-369.

Nazir Ahmad Zakir (1988), Notes on Iran: Aryamehr to Ayatollahs, p. 297.

Arafat’s visit to Tehran was on 17 February 1979, six days after the Islamist-Communist coup that swept away the Interim Government established after the Shah left on 16 January.

Oved Lobel, ‘Tehran’s Russian Connection’, Middle East Quarterly, Winter 2022. Available here.

Lobel, ‘Tehran’s Russian Connection’. See also: Yonah Alexander and Milton Hoenig (2008), The New Iranian Leadership: Ahmadinejad, Terrorism, Nuclear Ambition, and the Middle East, p. 22.

Richard Pipes (1990), The Russian Revolution, pp. 394-399.

Ronen Bergman (2008), The Secret War with Iran: The 30-Year Clandestine Struggle Against the World’s Most Dangerous Terrorist Power, p. 55.

As Tony Badran has explained, it was a Lebanese PLO terrorist, Anis Naccache, who ended up handling the Khomeinist file, coordinating with three of the Imam’s agents: “Mohammad Saleh Hosseini, who was active in Iraq where he made contact with [Arafat’s] FATAH before coming to Lebanon in 1970; Jalaleddin Farsi, an Islamic activist and teacher who would run for president in 1980 as the Khomeinist faction’s candidate (before disclosure of his Afghan origin disqualified him); and Mohammad Montazeri, son of senior cleric Ayatollah Hossein-Ali Montazeri, and a militant who had a leading role in developing the idea of establishing the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps once the revolution was won.”

The initial idea for the IRGC, though, came from the PLO’s Naccache, at least according to him. Fearing a counter-coup—and not unreasonably, since there was such an attempt in July 1980—“Naccache claims that Jalaleddin Farsi approached him specifically and asked him directly to draft the plan to form” the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution. The PLO then assisted in setting up the IRGC inside Iran after the Revolution (see footnote 48). As Badran notes, “The formation of the IRGC may well be the greatest single contribution that the PLO made to the Iranian Revolution.”

Bergman, The Secret War with Iran, p. 54.

“Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps” is the English name given to what the clerical regime tends to call Sepah-e Pasdaran (the Army of the Guardians) or Pasdaran-e Enghelab (Guardians of the Revolution).

Contrary to the official Hizballah narrative of being founded as a “resistance” to Israel’s invasion of southern Lebanon after 1982, the Lebanon-based IRGC had been in existence for nearly a decade by then. Even the name “Hizballah” was not new: it was already in use for Khomeini’s Islamic Republic Party (IRP) within Iran, had been in the 1970s and would be into the 1980s used region-wide by Khomeinists, and the Khomeinist militants had long been known as hizballahi.

Oved Lobel, ‘Becoming Ansar Allah: How the Islamic Revolution Conquered Yemen’, European Eye on Radicalization, 24 March 2021. Available here.

Afshon Ostovar (2016), Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, p. 45.

Note that the role of the PLO within Iran after the Islamic Revolution seems to have been wildly exaggerated. Claims circulated in 1979-80 of thousands of PLO operatives in Iran. The reality seems to have been in the dozens. The PLO was given an “Embassy”, the building that had previously housed the Israeli diplomatic mission in Tehran, and there was PLO military involvement in forging the IRGC institutionally immediately after Khomeini took power. But Artesh (the regular military) balked at having Palestinians involved with them, and, since Khomeini already believed Artesh had “the Shah in its blood” and did not want to provoke them any more than necessary before he was in a position to contain them, Khomeini acceded to Artesh’s objections. The Imam also soon had reasons of his own for limiting the PLO presence. It took four years after the Shah fell for Khomeini to fully consolidate the Islamic Republic and his factional enemies in that period, Islamists and Leftists, all had their own PLO ties: allowing a major PLO presence would have made Arafat a player, and perhaps arbiter, of Iranian politics. See: CIA Memorandum, ‘Palestinian Presence in Iran’, 1 August 1980. Available here.

Relations between Arafat and Khomeini began deteriorating soon after their victory lap in Tehran in February 1979. Arafat’s utility to the Islamic Revolution rapidly hit diminishing returns. There were ideological issues; the Islamist hopes of drawing the PLO in their direction went nowhere. If Khomeini had any inkling Arafat liked “playing tiger” with his bodyguards, that cannot have helped. And the Imam drew the line at Arafat interfering in Iranian domestic politics. Arafat thought he could play the same games he did with the Arab States, keeping his options open by having relations with the regime and its opposition (especially MEK in the Iranian case), able to use one to pressure the other to get his way, and raising his own stature by offering to be a mediator, while being positioned to benefit if one side or other prevailed absolutely. Khomeini was having none of that in the post-revolutionary struggle against his erstwhile allies. Arafat was put in his place and then jettisoned when he tried to split the difference one time too many, over Khomeini’s war with Saddam Husayn’s Iraq.

Bergman, Rise and Kill First, pp. 368-369.

In 1975, the Islamist-Marxist balance within MEK was tilted sharply towards Islamism with the departure of a Marxist contingent, led by Hosayn Ruhani, which called itself Sazman-e Peykar dar Rah-e Azadi-ye Tabaqe-ye Kargar (“The Organisation of Struggle/Combat for the Emancipation of the Working Class”). Ruhani, the son of a cleric incidentally, had become convinced he made an error in equating Islam with revolution. This “utopian” folly set aside, Ruhani was sure his new Marxist faith was “a true science, like physics, revealing the iron laws of historical change”. Peykar, by assassinating Americans, military and civilian, in Iran in 1975 and 1976, came to Western attention, but it was never definitively understood how Peykar related to MEK, an ambivalence captured in Peykar being called “the Marxist Mojahedeen” in the West.

While regarding the U.S. as the Main Adversary, Peykar also bitterly rejected the Soviet Union and Red China. The only Communist State that Peykar took inspiration from was Enver Hoxha’s Albania. Peykar was significantly debilitated by the Shah’s government in 1976 and publicly abandoned “armed struggle” in 1977. It was unprepared for Revolution in 1978 and its activities were limited to some political agitation in the last weeks of the Imperial Government. Initially throwing its support behind the “Islamic liberals” (LMI), Peykar dabbled with the Maoists in Kurdistan during the spring 1979 uprising, and then turned to the Fedayeen. Involving itself in the Fedayeen’s internal politics, Peykar supported what became the Fedayeen Minority, but this blew back into factionalism within Peykar.

Divided and opposed by the most powerful Leftists—the Fedayeen Majority and Tudeh—Peykar was defenceless when the Islamic Republic’s security forces came for it in late 1981, shortly after the purge of MEK and the remaining “Islamic liberals” around then-president Abolhassan Banisadr. Peykar’s co-leader Ali Reza Sepasi was arrested in February 1982 and rapidly murdered in prison. Ruhani had tried to save himself by siding with Khomeini, making an abject “confession” on State television in May 1982 that Marxist “deviationism” was a tool in the hands of the Americans against the “truly anti-imperialist people’s regime” of “the Imam”. Ruhani apologised for spreading “false ideologies” and said his time in Evin Prison had helped him see that Islam was the Revolution and the Imam was Islam. It did not save Ruhani, who was put to death in 1984, after Khomeini had made a clean sweep of the Left, using Tudeh to take down the Fedayeen Majority and then dismantling the friendless Tudeh.

See: Ervand Abrahamian (1999), Tortured Confessions: Prisons and Public Recantations in Modern Iran, pp. 150-154; and, Behrooz, Rebels with a Cause, pp. 121-124.

CIA Intelligence Assessment, ‘Iran: The Mujahedin’, August 1981.

The Mojahedeen of the Islamic Revolution Organisation (Sazman-e Mojahedin-e Enqelab-e Eslami), generally known by the acronym MIR, was the “Islamic Amal” equivalent when it came to MEK, the intermediary splinter fostered by the Khomeinists that was subsequently folded into the IRGC. MIR was created in April 1979, declaring its split from MEK on the ideological grounds that MEK included Marxism in its ideology and this was anathema to Islam. In practical terms, the difference was that MEK sought to retain its autonomy and disagreed in various ways with Khomeini—eventuating in the violent confrontation up to mid-1981—while MIR was wholly loyal to the Imam as leader of the Islamic Revolution. The former MEK leaders in MIR were gradually brought formally into the IRGC over the next few years, most prominently Mohsen Reza’i, the commander-in-chief of the IRGC from late 1981 until 1997. (It was after Reza’i’s dismissal that space was cleared for his rival, Qassem Sulaymani, to take over the IRGC’s Quds Force.) MIR was in all practical senses an extension of the IRGC by the time Reza’i became IRGC chief and the ambiguity was ended in 1986 with the de jure dissolution of MIR. See: Steven K. O’Hern (2012), Iran’s Revolutionary Guard: The Threat That Grows While America Sleeps, p. 18.

Matthew Levitt (2013), Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon's Party of God, pp. 28-31.

Fouad Ajami (1986), The Vanished Imam: Musa al-Sadr and the Shia of Lebanon, pp. 194-195.

Cooper, The Fall of Heaven, p. 296.

Marius Deeb ,‘Shia Movements in Lebanon: Their Formation, Ideology, Social Basis, and Links with Iran and Syria’, Third World Quarterly, April 1988. Available here.

For all the Soviets’ involvement across the spectrum of the Shah’s enemies, the KGB did letter better than the CIA in reading events. The Centre issued an assessment at almost the same time as the CIA, in the summer of 1978, concluding that the Shah’s government was too powerful to be overthrown. Moreover, the KGB persistently misread Khomeini’s intentions, partly because of its wishful thinking about the power of “religion”, believing any successful revolution would have to come from Communists, and partly because it repeated the CIA’s error in simply not listening to Khomeini’s tapes or reading his writings, which were readily available in Iran. See: Andrew and Mitrokhin, The World Was Going Our Way, pp. 181-182.

Cooper, The Fall of Heaven, pp. 349-350.

Egypt’s president, Anwar al-Sadat, was one of several people to warn Al-Sadr against the trip to Libya. Sadat, who had the measure of Qaddafi very early, did not believe any assumptions should be made about what the tyrant was capable of. Sadat had long called Qaddafi “the crazy boy” and dismissed Qaddafi’s Green Book, the ideological statement of his Islamic socialist Jamahiriya regime, as being in size and intellectual content “no bigger than a toaster manual”. See: Judith Miller (2011), God Has Ninety-Nine Names: Reporting from a Militant Middle East, p. 211.

Cooper, The Fall of Heaven, p. 350.

Ajami, The Vanished Imam, pp. 168-171.

Cooper, The Fall of Heaven, pp. 386-387.

Qaddafi, to his dying day, officially denied knowing what had happened to Musa al-Sadr, saying the cleric and his aides had got on a plane to Rome and that was the last he had seen of them. But, of course, the crime was so blatant that this was inadequate. A more plausible denial of responsibility Qaddafi got into circulation as rumour in the Arab world was that “zealous” deputies of his had murdered Al-Sadr without the permission of the Maximum Leader. Another response from Qaddafi came nearer to admitting he had assassinated Al-Sadr.

On 25 September 1978, a month after Al-Sadr’s vanished, Qaddafi met in Damascus with the rulers of Syria, Algeria, and South Yemen. The four radical Arab States were coordinating their response to the Camp David Accords: they demanded all Arab States sever diplomatic relations with Egypt for making peace with Israel. There had been protests when Qaddafi landed, with placards reading, “Oh Arabs, where is the Imam?”, and Qaddafi was visited in Damascus by a delegation of four Lebanese Shi’a clerics. Al-Sadr’s followers understood he was mortal, the clerics said. His death they could accept, but not that Al-Sadr could be “dissolved like some grain of salt”. Qaddafi responded: “I am told Musa al-Sadr is an Iranian, is he not?” Qaddafi often emphasised his status as a Bedouin—this is why he took his tent with him wherever he travelled—and he was a Sunni. This was the pedigree of an Arab; there was no room for Persian Shi’is. Qaddafi had curtain-raised for the kind of rancid sectarianism that would become much more common in the Middle East in later decades.

See: Ajami, The Vanished Imam, pp. 185-186.

Another piece of evidence in the same direction: Mohammad Saleh Hosseini, one of the Khomeinists working in lock-step with the PLO in Lebanon, told an Amal official soon after Al-Sadr’s disappearance, “your friend isn’t coming back.”

Cooper, The Fall of Heaven, pp. 415, 479.

Ajami, The Vanished Imam, p. 188.

Cooper, The Fall of Heaven, pp. 251-252.

Reported by AFP, 24 October 1978, quoted in: Kenneth deGraffenreid (1981, March 6), ‘Hostile Intelligence Threat: Terrorism’, National Security Council Memo, p. 35. Available here.

Cooper, The Fall of Heaven, p. 479.

Cooper, The Fall of Heaven, p. 423.

Manouchehr Ganji (2002), Defying the Iranian Revolution: From a Minister to the Shah to a Leader of Resistance, p. 228.

Khomeini’s meeting at Neauphle-le-Château on 21 November 1978 with Faruq al-Qaddumi (or Farouk Kaddoumi), the head of the PLO “political department”, was particularly public, and Al-Qaddumi declared the PLO’s solidarity with the Khomeinist campaign against “imperialism” (i.e., the Shah). See: Nicki J. Cohen, M. Page Jones, and W. Andrew Terrill, ‘Chronology of the Iranian Crisis: 1 January 1978 – 15 February 1979’, Analytical Assessments Corporation, October 1979. Available here.

Sterling, ‘Who Were Those “Student” Terrorists?’

This was reflected in Central Intelligence Agency reports. For example: ‘Weekly Situation Report on International Terrorism’, 4 October 1978 (available here), and, ‘Opposition Demonstrations in Iran: Leadership, Organization, and Tactics’, 21 December 1978 (available here).

Behrooz, Rebels with a Cause, p. 61.

‘The People’s Sacrifice Guerillas (Sazman-e Charikha-ye Feda’i-ye Khalq or Chariks)’, CIA National Intelligence Daily, 15 February 1979. Available here.

Cooper, The Fall of Heaven, pp. 251-252.

An example of the important psychological effect the Fedayeen had on Iran can be seen with MEK, a rival to the Fedayeen in the early 1970s. The trigger for MEK’s first terrorist plot, which ended with its leadership arrested, was the Siahkal incident. Not wanting to be outdone, MEK wished to bring off its own “spectacular”, but had to rush, hence seeking the help from Tudeh that undid them. See: Abrahamian, Radical Islam, p. 128.

Behrooz, Rebels with a Cause, pp. 63-68.

Cooper, The Fall of Heaven, pp. 248-249.

The Shah told his twin sister, Princess Ashraf, about his plans to make himself into a constitutional monarch in March 1977, and said the election to complete the process would be held in the summer of 1979. Ashraf was shocked and opposed the idea, but found her brother resolute on the point. See: Ashraf Pahlavi (1995), Time for Truth, p. 11.

Cooper, The Fall of Heaven, p. 250.

U.S. President Jimmy Carter had come into office in January 1977 lamenting “that inordinate fear of Communism which once led us to embrace any dictator who joined us in that fear”, and redirected U.S. diplomacy to promoting “human rights”. It might have been expected that the Shah, who had already opened up the entire Iranian prison system to the Red Cross after reports of torture in detention and then embarked on a political liberalisation program with “human rights” at its centre, would be treated as a showcase ally and claimed as vindication by Carter of his policy.

Instead, the Shah was not only given no credit—and the U.S. not only refused to accept responsibility for the consequences of its influence in Iran—but there was an active animus throughout the Carter administration, with the President himself once exploding in most un-Baptist terms, “Fuck the Shah!” Note that this was after the Shah had fallen, when this man who had stood with the United States for nearly four decades was simply looking for a place to die in peace. When twinned with Carter’s sheer inability to do the job of President, it produced throughout the Iran crisis a kind of malign incompetence in American policy that has only recently been exceeded.

The Iranian opposition, by contrast, felt the difference immediately. As early as November 1977, Ayatollah Khomeini was writing to his agents inside Iran to recommend ways of exploiting the new openness.

See: Behrooz, Rebels with a Cause, pp. 96-97; and, Gary Sick (1985), All Fall Down: America’s Tragic Encounter with Iran, pp. 66-67.