The Shah’s View of the Revolution that Felled Him

Iranian Revolution, Then and Now

For many months, there has been a protest movement against the Islamic Republic in Iran.1 Since no later than 16 September, the day Iran’s “morality” police killed 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, the character of the protests has been outright revolutionary. This past Wednesday, 26 October, was the fortieth day since Amini’s death, and the memorial marking the occasion was politically charged as the opposition mourned a martyr—an echo of one of the key dynamics of the 1978-79 Iranian Revolution.2

26 October was also the anniversary of the day, in 1919, when Iran’s last Shah, Muhammad Reza Pahlavi, was born, and some activists highlighted the convergence of these two events. If the current situation is, as many Iranians in the country and in the diaspora hope, a revolutionary one, then it is natural to focus on the last Revolution—to ask how this ever happened: How did the clerical despotism Iranians are now fighting get to power? And if, as a probable majority of Iranians now believe, the 1978-79 Revolution was a terrible wrong turning, does the way forward involve going back and directly undoing the original mistake, i.e., restoring the monarchy? This would, of course, involve coming to a conclusion about the nature of the Pahlavi dynasty.

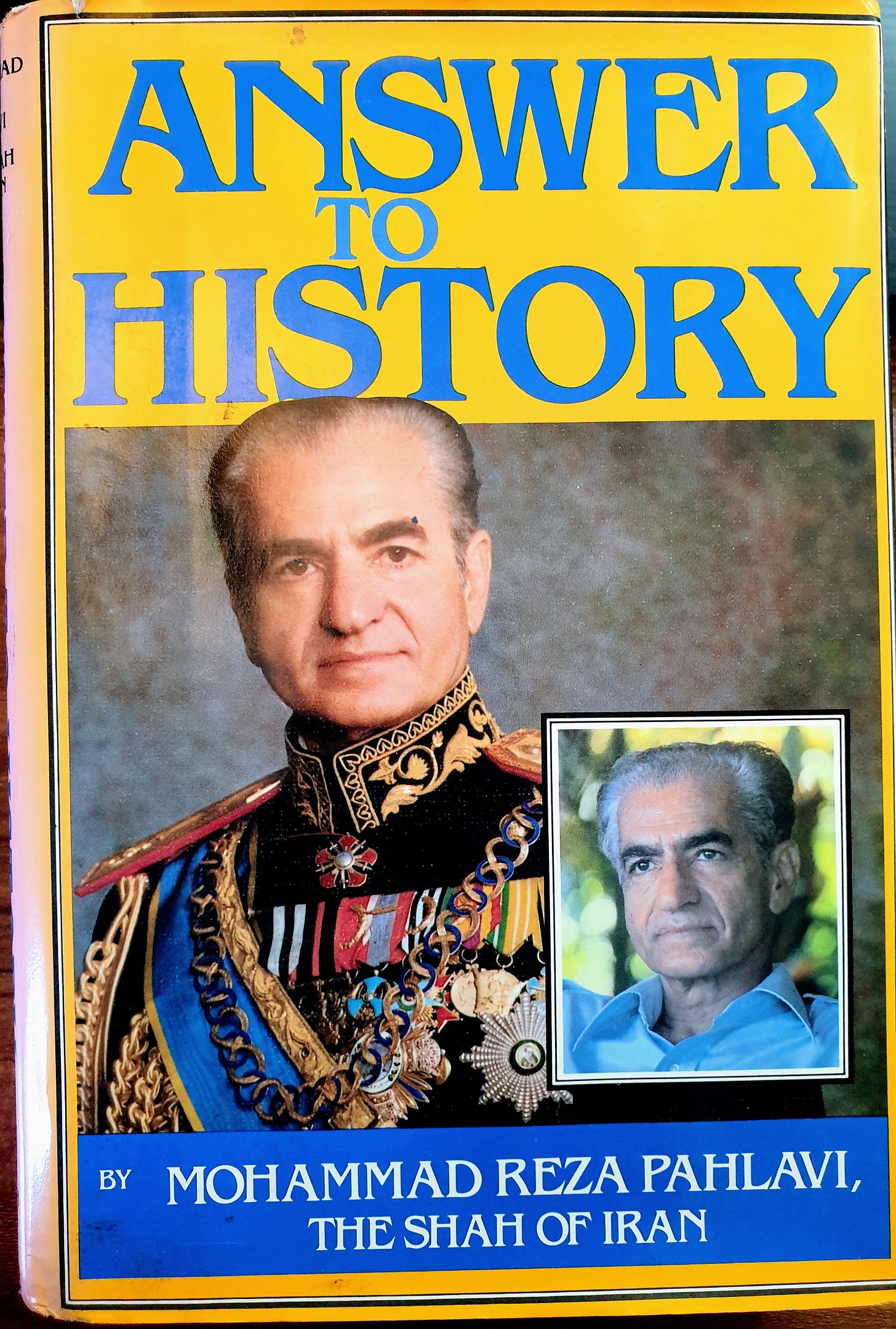

One view bearing on these questions was given by the late Shah himself. Having been unwilling to shed blood in Tiananmen-style to remain in power, the Shah left Iran on 16 January 1979. Diagnosed with terminal cancer in January 1974, the Shah succumbed to it in exile in Egypt on 27 July 1980. A few days before his death, the fallen monarch had completed a memoir, Answer to History.3

THE SHAH’S UNDERSTANDING OF THE REVOLUTION

Perhaps understandably, after the trauma of Revolution, the book is not the Shah at his best; it is shot through with conspiratorial and, indeed, contradictory thinking. For example, the Shah defines the “convergence of forces” that brought him down—while specifying they were not a consciously “organized plot”—as “the international oil consortium, the British and American governments, the international media, reactionary religious circles in my own country, and the relentless drive of the Communists”.4 Now, it has to be said that, although this is quite paranoid, when unpacked, this is not completely wrong, even if it is exaggerated and/or distorted.

It really was an oil deal in late 1976 that helped set the conditions for the collapse of the Shah’s government. And the Shah’s complaints about the relentless international media agitation against his government for often fabricated human rights abuses—and the same media’s near-complete silence about the unrelenting atrocities of the Islamic revolutionary government that replaced him—are unarguable.5

The Shah’s definition of the enemy coalition, “the clergy (the Black reaction) and the Communists (the Red destruction)”,6 was likewise well-founded, and even the Shah’s belief that within that coalition it would be the Communists who came out on top over the clergy led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini7 was a reasonable error at the time he was writing: the Soviet-controlled Tudeh (Iranian Communist Party) played a significant part in the Revolution itself and in the aftermath, under KGB guidance, in the construction of the new Islamic Republic’s security forces—and this was done in the hopes of supplanting the Black with the Red.8 Khomeini ultimately prevailed, but in the summer of 1980 most would not have bet on “a frail and crazy old man”9 and his “reign of terror and stupidity”10 to outplay Communists who had sixty years’ practice at global revolutionary terror.

Where the book is at its most conspiratorial, and least well-founded, is when assessing the actions of America and Britain.

The British come out of things especially badly, and not just during the 1978-79 revolutionary period, where the Shah would have been entirely justified in feeling he had been let down by British Ambassador Anthony Parsons. In fairness to the Shah, he is upfront about this bias, saying he “talked often [with his father] of British treachery”,11 and had “a longstanding suspicion” of Britain’s intent and policies, a view he “never found reason to alter”.12 The mutinous Prime Minister in the early 1950s, Mohammad Mosaddegh, is said to have been a “suspected” British agent.13 The British are said to have been involved in founding the Tudeh.14 The British are accused of having a hand in the assassination attempt by Fakhr Arai against the Shah in February 1949, and there is a suggestion that it might have been “subtle British propaganda” that enabled the blending of two otherwise opposed ideologies to create “Islamic Marxism”.15 All of this is ludicrous.

When it comes to the Americans, the Shah gives contradictory views. At some stages, the U.S. is said to have wilfully “undone” the Imperial government.16 It is added that the only “coherence to Western policy” over Iran was “a successful effort to destroy me”,17 and it is suggested that some parts of the State Department had a strategy of using Islamism as a bulwark against Communism,18 an idea sometimes known as “the Green Belt”.19 The CIA is repeatedly accused, in collaboration with “Big Oil”, of orchestrating the first anti-Shah student protests during a tour of the U.S. in 1959.20 At other stages, the U.S. actions that did help undo the Shah are put down to incompetence and unreliability. It might be “difficult to believe that the Iranian disaster was simply the result of short-sighted or non-existent policy and unresolved conflicts within the American government”, the Shah writes, but the record “does not allow any other conclusion”.21 Had the Shah stuck to this view, there would be little to argue with.

The Shah writes, “I never knew from one day to the next what U.S. policy was, or how reliable it was”,22 and it was difficult to discern a point where “the U.S. would be willing to stand up and fight” for the mutual security arrangements it had with Iran.23 Nobody who has reviewed the events of 1978-79 comes to any other conclusion, nor that U.S. Ambassador William Sullivan was the fulcrum of this confusion. The Shah writes that Sullivan would persistently reiterate the U.S.’s full support for his government, while constantly saying he had “no instructions” from Washington, so could never confirm what the U.S.’s official policy and advice were. Naturally, this left the Shah feeling “isolated and cut off” from his Western friends.24 If anything, the Shah is too soft on Sullivan, whose catastrophic misunderstanding of what was happening led to him being gulled by Khomeini’s agents like Mehdi Bazargan and effectively ending up advocating for the Islamists’ program, beginning with the decapitation of the Army.25 For Iranians who believe that America supported the Revolution, Sullivan’s behaviour is the primary evidence—and it is not unreasonable; it really is difficult to believe anybody could have been that incompetent.

There is bitterness in the account of President Jimmy Carter’s hesitancy to allow the Shah to get medical treatment in the U.S. after he had been deposed,26 and an objective observer can only agree that this was shameful. As one biographer who is hardly an apologist for the Shah noted, the world had accepted with equanimity Idi Amin, a truly monstrous and rapacious tyrant, going into safe exile to live off stolen loot, yet the Iranian monarch—who simply cannot be compared to Amin in terms of the repressiveness of his government, nor in terms of his personal wealth, whether in power or in exile—was hounded by the terrorist gang that seized Iran, whom the Western press lionised and Western governments sough to appease, and would have been “denied even the dignity of a quiet corner to die” if it had not been for the decency of Anwar al-Sadat.27

One of the strangest parts of the book is about the Soviet Union. The Shah was in so many ways the supreme Cold Warrior, and that is reflected in the book: he notes that the Cold War began in Iran, with the Azerbaijan crisis in the spring of 1946,28 and “Iran placed itself ideologically squarely in the camp of the Western democracies”.29 He is clear on Soviet ideology and conduct, that Moscow was “relentless[ly] striving towards world domination” and were patient about it, willing to take “a step or two backward”, while never losing sight of their aims.30 There is a reference to “the Soviet Union’s dogged determination to dominate the world”.31 The Shah (rightly) takes credit for suppressing the Communist rebellion in Oman, and recognises the danger of Communist infiltration in Africa, often using Cuban troops,32 particularly through Colonel Muammar al-Qaddafi’s Libya.33

Understanding the nature of the Soviets, then, and the Communist role in the Revolution, it is one thing for the Shah to say he endeavoured for “good neighbourly relations” with all34—Iran shared a 1,200‐plus-mile border with the Soviet Union—and even to buy into the (false) idea, as most Westerners did, that Romania was seriously autonomous within the Soviet socialist camp,35 but the kind words about Nicolae Ceausescu and Leonid Brezhnev are a bit much,36 and the statement that, by late 1978, “it almost seemed as if the Russians were more concerned about Iran than the Americans”,37 is flabbergasting. The same is true of the even-less-caveated statement that “[Communist] China was among the few nations interested in a strong Iran”.38

The actual chapter on the 1978-79 Revolution, entitled appropriately “The Unholy Alliance of the Red and Black”,39 is largely free of the conspiratorial material that appears earlier in the book. The Shah discusses his liberalisation program, which backfired: intended to meet the reasonable demands of the opposition and thereby neutralise the radicals, it emboldened the worst people by making the state appear weak. The comments on the Western media being at every stage hopelessly wrong and biased about what was happening in Iran are uncontroversial. As the Shah notes, this began earlier, when the media reported on abuse and torture in Iranian prisons; the scale was greatly exaggerated, but once the Shah became aware of it, the whole prison system was opened up to the Red Cross and the malign practices entirely ceased. This remedy got nothing like the coverage of the initial complaint. The Shah is simply correct when he says that the number of political prisoners never exceeded 3,200, the majority of whom were people charged with terrorism, and that SAVAK had only around 4,000 employees. The influence, pervasiveness, and brutality of the Shah’s secret police is one of those myths that will not die. A recent article in The Atlantic is a case in point, arguing absurdly: “The Shah wasn’t just any dictator. He was an exceptionally brutal one.” Anybody who spent any time in Imperial Iran, including liberal Western journalists who were generally inclined against the Shah, realised pretty quickly that the image of the bloodthirsty SAVAK police state cultivated abroad by anti-Shah activists was false.40 The timeline of events and the various changes in policy, such as Prime Minister Jafar Sharif-Emami’s Islamization measures from late August 1978, are told straightforwardly. The curious, unannounced arrival of U.S. General Robert Huyser in early January 1979—which looms very large in the imagination of Iranian monarchists who believe the Americans betrayed the Shah—is described as playing a key role in the Iranian Army remaining neutral when the Islamists made their move after the Shah’s departure. The nature of Huyser’s mission remains contested.

It is quite clear from the independent evidence that the counterfactual where a lethal crackdown saved the Imperial government was never really an option, since the Shah would never have given that order, and the book underlines that. The Shah writes that he had “wondered … whether stronger action … could have saved my throne and my country”, noting: “my generals urged me often enough to use force in order to re-establish law and order”. The Shah goes on: “the price in blood would have been a hundred times less” than what happened with Khomeini’s triumph (which is true). But he would never have done it. The security forces were instructed, “Do the impossible to avoid bloodshed”, since “a sovereign may not save his throne by shedding his countrymen’s blood … [A] sovereign is not a dictator. He cannot break the alliance that exists between him and his people.”41 The proof that this is not a retrospective view is in the outcome: with the offer—indeed, the pressure—to let the military shed blood to save his government, the Shah refused and chose instead to leave his country. For all the descriptions of the Shah as “weak” and “indecisive” during the crisis of 1978-79, on this he held absolutely firm.

THE SHAH’S VISION

Where the book is most substantively useful is not as a work of history, but as a window into the Shah’s mind. What is most apparent is that his bedrock assumptions and frameworks are all Western.

For example, the Shah was clearly motivated by a sense of history, and it is coloured by a deep Persian pride. He says: “Rome merely imitated Persia and frequently copied her methods”, and he contends that Alexander of Macedon did not bring Greek culture to Persia, but took over the Persian Empire and effectively assimilated to Persian civilisation,42 which is actually the view of many historians.43 It is notable, too, that despite the Shah being a devout Muslim he writes that “Iran suffered an Arab invasion” [italics added].44 But even his read of Persian history is shaped by Western categories. Cyrus is said to deserve the moniker “the Great” because he was “the first advocate of human rights”.45 More broadly, the Shah’s “passion for history and for great men” is recognisably in the tradition of Thomas Carlyle, rather than Islamic historiography.46

What the Shah wanted was for Iran to achieve “Great Civilisation”, and when explained he essentially means Westernisation.47 “The question is to evolve or not evolve, to remain a docile member of the Third World or to attempt to cross the threshold and enter into modern civilisation”, he writes.48

The Shah’s formative education was in France and the influence of the secular tradition in that Christian country shows up in his definition of Progress, and the terminology employed: the “Middle Ages” is his short-hand for backwardness;49 he refers to the role of “Providence”;50 “inquisitional” is used to describe the negative role an over-powerful clergy can play, and he almost seems to draw on Protestant polemic citing “the Spanish Inquisition” and “Torquemada” as the worst cases of this.51 Notably, the Shah firmly believed in Christendom’s distinction between spiritual and temporal, religious and secular.52 Another way in which this shows itself is when he notes that he had been very open to, and enjoyed engaging with, Western journalists, even hostile ones—which is true: one can still view the clips on YouTube—not least because “argument and debate sharpen the mind and help clarify one’s own thinking”,53 a near-perfect statement of (classical) liberal beliefs.

The thing the Shah is evidently most proud of from his reign is the White Revolution, begun in January 1963, which was meant to create a “modern and progressive Iran”. The reform package fused together all the strands in his thinking: Persian greatness, Westernisation, and Islamic devotion. A major part of the White Revolution was land redistribution, part of his effort to reduce economic inequality. The Shah was not a free marketeer; he cites the Qur’an as justification for common ownership of resources like water, among other things. The reforms included smaller things like creating “green belts” around cities, and major social changes like creating a corps of teachers to improve literacy and education in the villages.54 As the Shah himself notes, this ended up being a double-edged sword: it succeeded on its own terms, but it ended up bringing too many people into universities. His phrasing of the problem might be contested—“They had received so much without any effort that it appeared natural to them to claim ever more. Like spoiled children, these students caused so many confrontations that Iranian universities finally sank into anarchy”55—but the phenomenon was very real. Other elements of the White Revolution were the creation of a robust welfare system and universal healthcare (regarded as “the principal objective of a government”), and trying to root out corruption.56

There was a cultural element to the White Revolution program, uncovering and reviving for a mass audience the Persian past. This met resistance. “The concept that all things belonging to the past were reactionary, anti-progressive, and dépassé was widespread among Iran’s bourgeois city dwellers”, the Shah writes.57 He could have added that a lot of Muslim conservatives were unhappy with the official prominence given to Iran’s pre-Islamic past. The change from the Islamic calendar to the Persian one in 1976 became a particular flashpoint. The flourishing of the artistic scene, in which Empress Farah was “crucial”, included not just ancient Persian glories but the avant-garde58—another source of tension.

In many ways the most important part of the White Revolution—and the one that provoked Khomeini’s first revolt in 1963—was the drive for female equality. “Justice and common sense required that women enjoy the same political rights as men”, the Shah writes. “When half the population is denied education and is forced to live in the past, the whole of society suffers the consequences.” He saw equality of the sexes as both an Islamic and Persian truth. Suffrage was made truly universal in the elections for the Majlis, and the veil was a matter of “their choice”, though he clearly had a personal inclination against the chador as something that can “inhibit activities” such a sports.59

Given some of the outlandish things in the book, it is only fair to note that there are numerous instances of sound judgment, too. The remark that “America’s postwar history is an uninterrupted demand that the rest of the world resemble America”60 feels very contemporary. “Western policy in Iran, and indeed around the world, is dangerously short-sighted, often inept, and sometimes downright foolish”,61 is as good a summation of the 1970s as exists; some would say little has changed. He understood the uselessness of the United Nations.62 The Shah shrewdly saw that the central mistake of the U.S. enterprise in Vietnam was President Kennedy conniving in the assassination of Ngo Dinh Diem,63 and that Stalin had been “the great victor” in the Second World War.64 A darkly amusing place where the Shah was wrong is asking rhetorically, “what interest could the mullahs have in the nuclear power reactors I was planning and building?”65 The Shah makes a reasonable case in saying: “Iran truly was the only nation capable of maintaining peace and stability in the Mideast. My departure has changed all that.”66 And he is almost certainly correct that the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan would not have happened without his fall.67

THE SHAH AND RELIGION

The article in The Atlantic mentioned above contended that the Shah followed in the footsteps of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Turkey in engaging in an “orchestrated attack on Islam”. This simply is not true. It was more true of the Shah’s father, Reza Khan (r. 1925-41), who was “greatly influenced” by Atatürk, and hoped to “emulate” his transformation of Turkey,68 including with enforced social changes, above all the banning of the veil, but the Shah was, as he notes, “far less intransigent. During my reign, women and girls were perfectly free to wear, or not to wear, the chador”.69

The Shah was—unlike his father and Atatürk—personally very religious. He recounts his survival in early childhood of a bout of typhoid fever and serious accident, which he attributes to the intervention of Imam Ali and Abbas ibn Ali, respectively, and his later survival in office of several assassination attempts are regarded as “miraculous” and a sign of God’s will: only He can decide when life begins and ends, so the Shah’s survival suggested to him that the Almighty had work left for him to do.70 He did not think of this as a private matter. The Shah believed his role as King included being Defender of the Faith, and his government, among other things, heavily subsidised and supported the clergy, the mosques, and the shrines.71

It is worth quoting at length the Shah’s outlook on this matter:72

My faith has always dictated my behaviour as a man and as a head of state, and I believe that I have never ceased to be the defender of our faith. An atheist civilisation is not truly civilised and I have always taken care that the White Revolution to which I have dedicated so many years of my reign should, on all points, conform to the principles of Islam.

I believe that the essence of Islam is justice, and that I followed the Holy Koran … when our White Revolution abolished privilege and redistributed wealth and income more equitably.

For me, religious beliefs are the heart and soul of the spiritual life of all communities. Without this, all societies, however materially advanced, go astray.

The Shah clashed with elements of the clergy in the course of his reforms, but this was more a matter of power blocs and vested interests—the clergy were not pleased at having so much of their lands redistributed to peasants, for instance—rather than a clash with the faith per se. Khomeini and his lieutenants like Muhammad Beheshti were marginal figures within the formal clerical hierarchy in Iran. The primary Marja in Qom, Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari, was not only working in the last months of the Shah’s reign to thwart Khomeini politically; in late March 1978, Shariatmadari urged the Shah to kill Khomeini and said he could issue a fatwa licensing this. This was refused because SAVAK was not in the business of assassinations.73 After the Shah’s departure, Shariatmadari opposed the referendum in March 1979 to abolish the monarchy, and in December 1979 was the spiritual leader of an armed rebellion that broke out around Tabriz against the referendum formally refashioning Iran into an Islamic Republic.

One of the Shah’s main laments after his fall was that the clerical despotism would damage Shi’a Islam,74 and he concluded the memoir by saying that there was only one thing he could now do for his country, but it was “the most powerful [thing] of all—prayer”.75

In its way, this reality has become common knowledge in Iran: a saying among Iranians is that “the Shah believed in God, … and therefore feared the consequences of his actions”, unlike the mullahs, who abuse the faith for power.

CONCLUSION

The Shah was capable of self-criticism. In the memoir he acknowledges the “error” of the Rastakhiz Party, bluntly saying that what was created in March 1975 was a “one-party system”: despite the idea being to bring everyone together under one roof for the good of the nation, it produced negative outcomes.76 Overall, though, the fallen monarch’s self-verdict was: “Certainly, I had made mistakes in Iran. However, I cannot believe they formed the basis for my downfall. They were rectifiable with time. My country stood on the verge of becoming a Great Civilisation.”77 For some, Iranians and outsiders, this will seem like an obviously accurate summary of affairs; for others, it will seem hopelessly deluded. As of now, the argument over the Shah’s legacy continues.

Events in Iran are likely to heavily influence where the consensus ends up on the Shah. There is already, and has been for some time, a lot of interest in and nostalgia for the Shah’s time within Iran. The hideousness of the Islamic Republic has a lot to do with this, of course: in looking for an opposing model to the theocracy, it does not get more opposed than the Shah’s secular-ish, distinctly Persian, Westernising regime. There is also the demographic facts of Iran: about half the population are under-35; they have only ever known the deprivation, totalitarianism, and isolation the revolutionary clergy have imposed upon their country. When they look back at the monarchy—at the prosperity, the social freedom, and the respect an Iranian passport had around the world—they wonder how their parents could have failed to see what they had, and given in to what was a kind of mania in 1978-79.78 Especially confusing for some is that Iranians overthrew their monarchy at the very moment it had taken the greatest steps to remedy its deficiencies.79 The Shah always insisted Iran was an Empire—a mosaic population united by their Emperor—and his project was to maintain this “unity from above in order to realise a true imperial democracy”.80 If it should turn out the Islamic Republic was a brief Interregnum on the way to the fulfilment of that project, that will obviously influence how the Shah’s legacy is viewed.

All that is for the future. The legacy of the Islamic Revolution is much clearer. To highlight just two aspects:

First, the Iranian Revolution was a real Revolution—as in France or Russia, rather than a coup d’état—that not only radically restructured the state and society along ideological lines, but had an enormous impact on those areas “within the same universe of discourse”, inspiring and outright directing counterpart movements in numerous foreign states. The Shah was entirely correct to say that his “disappearance from the world political and economic scene” would create terrible opportunities for the West’s enemies, and that Khomeini’s victory would destabilise not only the Middle East but the world.81 The fall of the Shah marked the culmination of the Soviet offensive that had been carried out globally under the cover of détente in the 1970s, and the rise of the Islamic Republic emboldened the Islamist current that had been building in the region: if the West’s most loyal and powerful ally could be toppled and replaced with an Islamist regime, it meant it could happen anywhere. Al-Qaeda’s late leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, was particularly impressed with Khomeini’s achievement—and the Iranian regime returned the admiration down to his dying day. Clerical Iran dominates the northern Middle East—Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria, where it stands behind the crimes against humanity that have killed half-a-million people—and Yemen, while meddling in Afghanistan and many other places. Beyond the region, the Islamic Revolution is truly global, with outposts in Africa and Latin America, and its most recent project is assisting Russia’s attempt to eliminate Ukraine.

Second, the Iranian Revolution—far more than France or Russia82—was a people’s Revolution: the narrative of a “hijacked” Revolution, which is nurtured to an extent by the testimony of elite participants who miscalculated their own role,83 is false. However vaguely Khomeini’s program was understood, the Iranians rejected the Shah’s Westernisation program and chose theocracy that year. Many now regret that decision, which is potentially positive: admitting a mistake has many healthy consequences. But there is every difference in the world between admitting a mistake and pretending the mistake did not happen. It is very important for Iran moving forward that this history—and the responsibility that goes with it—be accepted.

REFERENCES

There have been intermittent protests in Iran that have been brutally suppressed—in December 2017, especially notably in November 2019, and November 2021—but nonetheless, sporadic protests began again in May 2022 and by early June the protests were getting larger. By the end of June 2022, Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamene’i, was clearly worried. The protesters’ individual issues could be labelled “economic”, but from the outset the focus was political: the clerical regime’s mismanagement that led to the economic deprivations. This was the case as the number of protests grew, and spread further geographically, in late August, with protests about a lack of access to water, for example, but already a generalised protest against the regime’s policies was beginning, such as against conscription and—as has become most important—the compulsory hijab for women.

The Islamists who rose against the Shah’s government in 1978 weaponised this tradition: they would deliberately get themselves and others killed in clashes with the security forces to ensure that six weeks later there would be another event to mobilise anti-regime sentiment around. One of Ayatollah Khomeini’s senior lieutenants later confessed that within the Imam’s inner circle, from where this cynical program was orchestrated, and among the volunteers who laid down their lives for Islam as they understood it, this was referred to as “doing the forty-forty”. See: Gary Sick (1985), All Fall Down: America’s Fateful Encounter with Iran, pp. 34-5.

The book was published in English in September 1980. The Shah wrote the manuscript in French originally, and its title was, “Réponse à l'histoire”. In Persian, the book was entitled, “Peaskh bah Tareekh” (پاسخ به تاریخ).

Answer to History, p. 23.

Answer to History, pp. 182, 187.

Answer to History, p. 103.

Answer to History, pp. 145, 188.

Oved Lobel, ‘Tehran’s Russian Connection: Whither Iran?’, Winter 2022, Middle East Quarterly. Available here.

Answer to History, p. 163.

Answer to History, p. 188.

Answer to History, p. 68.

Answer to History, p. 15.

Answer to History, p. 71.

Answer to History, p. 73.

Answer to History, p. 59.

Answer to History, p. 14.

Answer to History, p. 22.

Answer to History, p. 23.

There is no evidence that “The Green Belt” (or “The Green Corridor”) ever existed as a U.S. policy, but it is an idea that gained some traction among secularists in the Middle East in the 1979-80, particularly among monarchists in Iran who blamed the U.S. for the Islamic Revolution and among factions of the Kemalists in Turkey. The military officials who took power in the September 1980 Turkish coup softened the laik (secularism) policy to allow Islam a role in the state and society that was unprecedented in the republican era. The junta had its own reasons for doing this, but some Kemalists see these changes as a betrayal of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s vision and explain the deviation of their ideological kin by casting the Evrenists as American agents enacting “The Green Belt” scheme. The only “evidence” that is ever really offered for “The Green Belt” is the U.S. support for the Mujahideen in Afghanistan: this is a bizarre argument since the U.S. policy was reactive to the Soviet conquest of Afghanistan, but since the U.S. was drawn into Pakistan’s jihad, which had begun a half-decade earlier, it makes no sense at all.

Answer to History, pp. 22, 146.

Answer to History, p. 24.

Answer to History, p. 15.

Answer to History, p. 150.

Answer to History, p. 161.

Andrew Scott Cooper (2016), The Fall of Heaven: The Pahlavis and the Final Days of Imperial Iran, pp. 451-53.

Answer to History, pp. 29-33.

Abbas Milani (2011), The Shah, p. 426.

Answer to History, p. 79.

Answer to History, p. 137.

Answer to History, pp. 12-13.

Answer to History, p. 150.

Answer to History, p. 18.

Answer to History, pp. 134-35.

Answer to History, p. 131.

Ion Pacepa (1988), Red Horizons: Inside the Romanian Secret Service – The Memoirs of Ceausescu’s Spy Chief, pp. 8-9.

Answer to History, p. 132.

Answer to History, p. 170.

Answer to History, p. 134.

Answer to History, pp. 145-74.

The Fall of Heaven, pp. 238-39.

Answer to History, pp. 167-68. The Shah’s view that he held his office not simply by inheriting it can also be seen when he says that his welcome back to Iran after the Mossadegh coup was defeated was confirmation he had “truly been elected by the people”. Answer to History, p. 91.

Answer to History, pp. 37.

A significant school of thought among historians agrees with Pierre Briant that Alexander the Great was “the last of the Achaemenids”.

Answer to History, p. 38.

Answer to History, p. 36.

The Great Men that the Shah mentions as inspirational to him are: the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (r. 1519-56), the Russian Emperors Pyotr I or Peter the Great (r. 1682-1725) and Ekaterina II or Catherine the Great (r. 1762-96), the French rulers Henry IV (r. 1589-1610) and the “Sun King” Louis XIV (r. 1643-1715), and of course the Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte (r. 1804-15). His one difference with these people is that he “shudder[s] to think of my reign with clerical advisors”, since this could have ended up like the Islamic Republic. Answer to History, p. 64.

Answer to History, p. 175.

Answer to History, p. 138.

Answer to History, p. 47.

Answer to History, p. 54.

Answer to History, p. 189.

Answer to History, pp. 54-5.

Answer to History, p. 27.

Answer to History, pp. 101-15.

Answer to History, p. 116.

Answer to History, pp. 119-29.

Answer to History, p. 117.

Answer to History, p. 117.

Answer to History, pp. 117-18.

Answer to History, p. 27.

Answer to History, p. 21.

Answer to History, p. 136.

Answer to History, p. 28.

Interestingly, the Shah says that when he spoke to Winston Churchill, in 1942, he had recommended an invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe from the south, at the weakest point through Italy and/or the Balkans, which, as he notes, is what Churchill ended up advocating for, against the OVERLORD operation through heavily-fortified France. Answer to History, pp. 71-3.

Answer to History, p. 18.

Answer to History, p. 142.

Answer to History, p. 155.

Answer to History, p. 51.

Answer to History, p. 56.

Answer to History, pp. 57-60.

Answer to History, p. 148.

Answer to History, p. 60.

The Fall of Heaven, p. 315.

Answer to History, p. 179.

Answer to History, p. 190.

Answer to History, pp. 124-25.

Answer to History, p. 34.

The Shah recognised the craze or hysteria aspect to the Revolution, noting that the “forty-forty” protests—which he despised as a sacrilegious abuse of the faith—were needed to continue the inflamed atmosphere; the Islamists and Communists “could not afford to relax their agitation lest common sense prevail”. Answer to History, p. 159.

Iran was more politically open and broadly prosperous in 1978 than at any point not only during the Shah’s reign but in the country’s history. While this seems odd, the same thing happened in France and Russia: both monarchies were overthrown in the midst of serious reforms and replaced with regimes that were far worse on every metric. In truth, this is not a quirk or an irony or a paradox. As Alexis de Tocqueville put it: “Evils which are patiently endured when they seem inevitable, become intolerable when once the idea of escape from them is suggested. The very redress of grievances throws new light on those which are left untouched … if the pain be less, the patient’s sensibility is greater.”

Answer to History, p. 129.

Answer to History, p. 179.

A solid account that casts aside the “large, impersonal forces” perspective, setting out the French monarchy as it actually was—enraptured by the Enlightenment, socially mobile, and economically and technologically dynamic—and giving due agency to the zealots who orchestrated the revolutionary catastrophe can be found in Simon Schama’s Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (1989). The Russian Revolution is an even more severe case where individual contingency and happenstance dominated at every stage.

The Communists made the most terrible blunder with the Iranian Revolution—and, indeed, afterwards. The Fedayeen terrorists and the Tudeh collaborated with Khomeini against each other up to 1983, by which time none of them were left. But the “moderate” Islamists around the Liberation Movement of Iran (LMI), which gave Khomeini a broader reach into the middle class and the bazaaris, were equally foolish: they discovered too late who was using whom. Bazargan and Ibrahim Yazdi were quickly purged after acting as Khomeini’s “moderate” front men for a couple of months in 1979, and the LMI veteran who served as Khomeini’s some-time foreign minister, Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, ended up before a firing squad in 1982. Abolhassan Banisadr, the first president of the Islamic Republic (r. 1980-81), was not technically an LMI member, but he worked very closely with this set that helped create the deceptive image of Khomeini for Western audiences; he fled for his life in mid-1981 after being “impeached” by the “parliament”. For these people, the sense that something “went wrong” with the Revolution is undoubtedly quite genuine, in the sense that reality confounded their expectations: this is no reflection on the reality of the Revolution; it is a reflection of the time taken for them to realise the error of their expectations.