Millenarian Communism in Munster: The Anabaptists of the Early Reformation

A Radical Reformation Sect That Went Off the Rails

In February 2021, in the midst of the second lockdown, I published the below post on the Anabaptist Revolution in the German city of Munster. Vaguely topical as it is Easter Sunday, and since it is one of my favourite articles, not just about Christianity but overall, I thought I’d re-up it here for those who had not seen it while I finish off some new articles—both of the historical and contemporary foreign policy/terrorism kind—that will be put out over the next week. Happy Easter everyone — Kyle

In 1534, shortly after the onset of the Protestant Reformation, a radical sect from this new movement, the Anabaptists, seized the city of Munster in Germany and governed it for sixteen months as a millenarian cult in a manner so alarming it managed to bring together Catholic and Lutheran forces to put it down. The experience had a profound influence not only on the development of Anabaptism thereafter, but on the manner in which the Reformation more generally unfolded.

BACKGROUND

The controversy with the Anabaptists begins with the name: it is a pseudo-Greek rendering of “re-baptisers”, a misrepresentation by critics of their theology. Anabaptists believe that baptism should be a knowing pledge of faith and that child baptism is illegitimate, pointing to the fact that in the New Testament there is not a single infant baptism. The sect refers to “believers’ baptism”; its opponents see it “re-baptising” people. A more neutral descriptor would be Täufer (Baptiser). The Anabaptists drew on logical inferences in the teachings of Huldrych Zwingli, the Zurich Reformation leader killed with hundreds of his followers by a league of Catholic states in 1531, but the Swiss preacher personally was an unalterable foe of the Anabaptists, principally because their theology—by making baptism voluntary and the marker of belief—split the community into believers and non-believers, and Zwingli was as committed as the Roman Catholic Church to the idea of the whole society being within the Church.1

The Lutherans of the Holy Roman Empire had flirted with a populist approach to spreading their idea that salvation could be had sola fide (“by faith alone”), i.e. by believing the correct theology, as opposed to through good works, as Catholics taught. Where Catholics saw charity and other acts as intrinsic to the faith, Protestant polemic denounced this as letting people buy a ticket to heaven through deeds when Christ had so clearly set down that He alone was the “the way, the truth, and the life” [John 14:6]. The Farmers’ War—a massive, Anabaptist-inflected middle-class rebellion in the centre and south of the Empire from 1524 to 1525, whose suppression Luther had enthusiastically supported—spooked the Protestant Reformers and they turned firmly to the magisterial model, trying to capture local magistrates, namely the civil (which is not quite the same as secular) officers of the state, like local councilmen and Princes or Dukes, and the mainstream Reformation became a top-down process with a stress on order.

The Anabaptists—with their focus on free will of the individual and people’s behaviour in this life—were tactically in confrontation with the Lutherans, and theologically somewhat closer to Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. But the Anabaptists held in common with the other Protestants the belief that they could interpret the Bible for themselves, that the Spirit would work through them to reveal God’s true meaning, bringing the light of clarity by adhering to the text alone, piercing the darkness imposed by accumulated tradition and various corrupt authorities, state and clerical, that manipulated the text for their own ends. This approach to the text naturally yielded multiple sects, each claiming to have had the true doctrine revealed to them, and without the buffer of tradition or the guiding hand of authority some of these interpretations ended up in outlandish places. So it was with Anabaptism.

Protestant Zurich outlawed Anabaptism in 1526, even drowning four of them in the River Limmat, starting with Felix Manz in January 1527, the first martyr of the Radical Reformation. A few months later, the Catholic ruler of Austria, Archduke Ferdinand (r. 1521-64), a future Holy Roman Emperor, had Michael Sattler, the Benedictine monk whose Schleitheim Confession is the nearest the Anabaptists ever came to issuing a manifesto, executed for defiance of the Emperor and heresy. This was the Magisterial Reformation persecuting the Radical Reformation, exactly simultaneous with the old, Roman Church persecuting the Reformed believers.

The Anabaptists created an alliance with one magistrate within the Holy Roman Empire, Count Leonhard von Liechtenstein, which allowed them to control the town of Nikolsburg (now Mikulov in Czechia). In 1527, the Anabaptists abruptly lost their one foothold: the Catholic Habsburg Monarchy, with the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V at its helm, ordered Count Liechtenstein to clear out this nest of heretics and the man who was building up to be the “Anabaptist Zwingli”, Balthasar Hubmaier, was burned at the stake in March 1528. After this, the Anabaptists retreated into themselves, stressing their distinctness from the surrounding society, and the Biblical stories of the early Christians as a persecuted minority in a hostile world.2

It was in the context of the Anabaptists having been driven to a posture of self-conscious societal separatism that the Munster revolt took place. Jesus had said, “I came not to send peace, but a sword” [Matthew 10:34], and the radicals among the Reformers took this as instruction to assist in the ushering in of the Last Days.3

THE NEW JERUSALEM

The Reformation in Munster had been proceeding in conventional fashion, with Bernhard Rothmann as the city’s leading Lutheran preacher, churning out fierce anti-Catholic polemics. Franz von Waldeck, the Prince-Bishop of Munster, referring here to the whole principality of which Munster was the capital city, and even Emperor Charles V in faraway Vienna, had tried to repress Rothmann, who had, much to their chagrin, been protected—along with his teachings—by a vote of the city council in 1532. In early 1533, after an ill-fated attempt by Waldeck to use economic sanctions—confiscating saleable goods from merchants, for example—to pressure the socio-political elite in Munster into reversing course, full religious liberty was conceded to the city.

In the latter months of 1533, radical Reformers from the surrounding area began converging on Munster. Jan Matthys (or Jan van Matthijs), a baker from Haarlem, the very stereotype of a giant Dutchman, had become the Anabaptist leader in the Low Countries after Melchior Hoffman had been imprisoned in Strasbourg,4 and on 5 January 1534 he marched into Munster and declaring it “The New Jerusalem”. Matthys soon baptised over-1,000 people, including Rothmann.

No later than early February 1534, the Anabaptist presence in Munster had taken on a revolutionary character and by the end of the month the town council had been overthrown, formally through an election that the Anabaptists easily won with so many of their co-religionists having come to settle in the town over the previous weeks. The Anabaptists installed Bernhard Knipperdolling as Lord Mayor. Knipperdolling was a local merchant and disciple of Rothmann’s, who had bankrolled the preacher’s Lutheran agitation in earlier years.

Knipperdolling’s authority, generally rather nominal, was sufficient to persuade Matthys that his program for ethnic cleansing of Catholics and Lutherans in Munster should be modulated; where Matthys wanted to kill them all immediately, the ordnance issued on 25 February 1534 calling for the elimination of all “godless” residents of Munster, gave them a week, until 2 March, to depart.5 By early March 1534, the best estimates suggest about 2,000 Catholic and Lutheran Munsterites had fled their city, and about 2,500 Anabaptists from the surrounding areas had flooded in. Over the next fifteen months of Anabaptist rule, and siege, there were considerable fluctuations in the population number; the guestimates average out at about 8,000 total, with an even rougher breakdown: 2,000 adult men, 5,000 marriageable women, and 1,000 young children.6

There was some understandable resentment from the Germans in the city at the arrival of this Dutchman who proposed to tell them the proper way to practice religion. Hubert Ruescher, a blacksmith, declared in public before a crowd that it was “madness” this “stupid crazy liar” (Matthys) had called himself a prophet and seized the reins of government, despite knowing “nothing of the custom of this homeland”. Ruescher concluded that he was a dreadful prophet, “so often proven wrong in his predictions! My judgment is that as a prophet he gives shit!” Word of this outburst quickly got back to Matthys through the Anabaptist regime’s network of spies and Ruescher was dragged into a public square and murdered by Matthys with an axe and a handgun commandeered from the gathered crowd, the first victim of the Anabaptist regime. During the trial, the two alderman of the city, Herman Tilbeck and Henry Redeker, had worried aloud that things had gone a shade too far and that some kind of legal process was called for; they were promptly hauled off to prison. In the commotion, Matthys had somewhat lost the thread until another Dutchman, the illegitimate son of a village mayor, Jan Beuckelszoon,7 emerged from the crowd, brandishing a sword that kept others from reacting, to incite Matthys to finish what he had started. It was Beuckelszoon who had invited Matthys to Munster in the first place, having only himself arrived a few months earlier.8

With the willingness to kill demonstrated, the Anabaptists rather easily forced the registration of gold and silver possessions that were then confiscated as private property, money included, was “abolished”, i.e. seized by the Anabaptist regime.9 Food was likewise declared common property and the monasteries were looted.

This communistic impulse displayed by the Munster Anabaptists was not new in Christianity. In some ways, one could say the model of the Early Church was a form of Communism.10 As the Book of Acts [4:32-35] puts it: “The multitude of those who believed were of one heart and one soul; neither did anyone say that any of the things he possessed was his own, but they had all things in common. … Nor was there anyone among [the Apostles] who lacked; for all who were possessors of lands or houses sold them, and brought the proceeds of the things that were sold, and … distributed to each as anyone had need.” (Karl Marx’s slogan summarising socialism, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”, is self-evidently drawn from this Biblical passage, not that he seems to have realised it.) The fervent egalitarianism and utopianism, the belief in the perfectibility of man, of Pelagius (d. c. 420), Augustine’s great antagonist, was in the same communistic tradition, and the most prominent precursor to the Anabaptists in this vein is undoubtedly the Hussite faction around Tabor a century earlier. In the century that followed the Anabaptists, after the English King was killed and radical Protestant sects flourished under the republican Commonwealth, there were the Diggers.

There was a despotic bent to the Munster Anabaptists that was somewhat different to its predecessors, though. Front doors of homes had to be kept open at all times, abolishing private life.11 Two weeks later, on 15 March 1534, the Anabaptists banned the possession and reading of all books, except the Old and New Testaments, and tens of thousands of manuscripts were loaded onto large bonfires, a mass book burning in Germany that heralded the arrival of a totalitarian regime, almost exactly four-hundred years before its most infamous one.12

A REGIME UNDER SIEGE

Almost the entirety of the Anabaptist experience in Munster was conducted under a military blockade, albeit of varying severity over time. Prince-Bishop Waldeck, expelled from his capital, had reacted swiftly to quarantine the Anabaptist contagion, besieging the city of Munster on 28 February 1534 with his own Catholic troops and the landsknecht (German mercenaries). Waldeck received troops from neighbouring Princes to reinforce the siege: from the strongly Catholic Count of Hoogstraten Antoine de Lalaing and Archbishop-Elector of Cologne Hermann (who later had his own break with Rome); from the strongly Protestant Landgrave Philip of Hesse; and from the Duke of Jülich (and Cleves) John/Johann, who was somewhere in between.13 All rulers saw a threat in this radicalism spreading.

The Anabaptist leader, Matthys, was killed early in this drama, on 5 April 1534 (Easter Sunday), when he took up an axe and led a party of about thirty men through the Ludger Gate, believing God had mandated him to play the part of Gideon with the besieging armies as Midianites.14 Matthys’ band—generally described in the various accounts as having “sallied forth”, wonderfully capturing the absurdity of the situation—was surrounded and annihilated, the man himself dismembered, in all senses. Matthys head was displayed on a pole high enough for all the city to see and, the next night, one of the soldiers “affixed [Matthys’ genitals] to the revolving gateway of the Giles Gate”.15

A NEW LEADER: BRACED FOR ATTACK AND SPY GAMES

The 25-year-old Beuckelszoon took over as the new prophet. Later pro-Catholic sources would claim that Beuckelszoon “began his messianic reign by running naked through the streets of Münster in a wild religious frenzy; he then fell into a silent ecstasy for three days.” This is not implausible. When composure and clothing returned, Beuckelszoon appointed twelve Elders (or “Judges of the Tribe of Israel”) as an executive committee to help him administer a city government that was heavily militarized in nature. A reign of terror began, with the death penalty now being applied for “blasphemy, seditious language, scolding one’s parents, disobeying one’s master in a household, adultery, lewd conduct, backbiting, spreading scandal, and complaining”.16

One of the first things the Elders’ council did, on 8 April, was to establish contact with the besieging troops, especially the landsknecht, calling on them to cease their unjust aggression and to join “the Kingdom of God”, which seems to have had some impact. With an assault looming, Beuckelszoon made personal speeches at communion meetings, stressing the obligation of believers to defend God’s Kingdom on earth to the death. It worked. When the Catholic troops attacked on 25 May, they found that the Anabaptists’ faith in their cause and morale high: the Mauritz and Jüdenfeld Gates held; one-hundred of the attacking troops and fifty Anabaptists were killed.17

In June 1534, a female agent of the Anabaptist regime named Hille Feicken left Munster in a column of refugees to attempt to enter the camp of the besiegers and assassinate Prince-Bishop Waldeck. In this, Feicken believed she was imitating the example of Judith, who used her wares to get into the tent of the Assyrian General Holofernes during the siege of Bethulia and behead him. Feicken’s operation was apparently supported by the Anabaptist Mayor Knipperdolling, with conflicting accounts about Beuckelszoon’s view.18 Whether Feicken was given away by one of the genuine refugees or because she was dressed just slightly too smartly is uncertain.19 In either event, she was put to death by Waldeck’s troops.

POLYGAMY AND SEDITION

In the summer of 1534, Beuckelszoon, relying on “visions” from on high to justify his various policies, demanded that all women of age be married, and—in a situation where the besieged city was lopsidedly female (the oft-given statistic is that the ratio was 3:1)—for men to take as many wives as necessary to make this happen.

Anabaptism has attracted a great deal of interest from Communists because of its doctrines and practice against private possessions; the rebels of the Farmers’ War were state heroes in East Germany, for example, and in the case of the Munster millenarian regime it has led to Marxist historians advancing secular apologetics for its behaviour. The imposition of polygamy is one such case: the argument goes that Beuckelszoon was really seeking a material outcome, namely social stability, in the only way he could in a sex-unequal environment. In reality, there is no reason to think it was anything other than an ideological decision. For one thing: it did not lead to stability.

The polygamy order brought the Anabaptist regime as near as it ever came to internal collapse, provoking such outrage that a group of conspirators led by one Heinrich Mollenhecke, a former alderman, led a coup attempt and managed to imprison Beuckelszoon himself on 29 July 1534. Unfortunately for Mollenhecke, the townspeople had already established their cult-like devotion to Beuckelszoon: a mob, led by one of the twelve Elders, Tilbeck, who had recovered from his objections at Ruescher’s lynching, stormed the prison to free the “prophet”. Over the next four days, up to 2 August 1534, about seventy people accused of plotting against the Anabaptist regime managed to demonstrate they had not been part of the initial conspiracy and were released, while Mollenhecke and forty-eight others were massacred after “trials” that declared them—by definition since they opposed His divinely-appointed regime—enemies of God.20

Beuckelszoon had sixteen wives by the spring of 1535, motivated less by sexual avarice as later Christian polemicists would suggest than politics, which is to say religion under a theocracy—preserving the political order is serving the religion by definition. Beuckelszoon married into many important Munster families and thereby implanted his regime on more solid foundations.21 That said, Beuckelszoon did attempt to take at least one more wife in a case that does seem a lot more like whimsy. Elisabeth Wandscherer had boasted that no man could control her, and Beuckelszoon decided to put this to the test. As feisty as advertised, Wandscherer, after briefly living with Beuckelszoon, gave back the various gifts she had been given,22 and openly criticised the by-then “King” for living, as one author put it, “in insane luxury, surrounded by his harem, as his followers starved and died defending him”.23 Beuckelszoon personally beheaded Wandscherer in the marketplace on 12 June 1535—just two weeks before the Beuckelszoon regime’s demise, as it transpired.24

GOD’S KINGDOM ON EARTH

The episcopal troops made their second assault on the city on 30 August 1534.25 It was a narrower-run thing than what had happened three months earlier, but the city’s defences held and the attackers were repelled, creating considerable trouble for the discipline of the landsknecht-heavy Catholic troops.26

It was in the aftermath of this second victory that Beuckelszoon proclaimed himself King on 8 September 1534,27 indeed the “King of Righteousness Over All”, which, along with the imagery frequently used of Beuckelszoon as the successor to King David and his regime as the return of Zion and the fulfilment of the Book of Revelation’s promise of the thousand-year reign of the saints, made clear that what had started in Munster was not intended to stay there.28 Showing Beuckelszoon’s great skill in the use of propaganda for social control, he had prepared this announcement by having a goldsmith named Johann Dusentschuer “emerge” on the streets as a prophet as the August attack loomed, telling men who had only one wife to find another and in general demanding “Christian perfection” (as interpreted by the Anabaptists) to ensure victory. Once the victory had been achieved, Dusentschuer began to preach that Beuckelszoon should be King.29 As will be seen below, there can be little doubt Dusentschuer acted at Beuckelszoon’s behest: Beuckelszoon was very sensitive to anybody claiming the mantle of prophet.

Shortly after Beuckelszoon became King, there seems to have been a second, brief power-struggle, this time with his oldest associate, Knipperdolling. Knipperdolling seems to have had pretentions to prophethood, and also to have voiced some disquiet about the autocratic way Munster was being governed. After three days in prison, Knipperdolling seems to have gotten over his qualms.30

The twelve-member Elders committee was eliminated and the Anabaptist King appointed his Court. Down to the end, Knipperdolling served as Stadtholder, literally “place holder” and often rendered as “steward” or “viceroy”; in the context of Munster it meant Beuckelszoon’s deputy. Tilbeck became the Master of the Court. Bernard Krechting, a former pastor in Gildehaus, became the de facto commander in chief, keeping men at their posts guarding the wall. Bernhard’s brother, Henry Krechting, once a bailiff (Gaugraf) in Schöppingen, became Chancellor. Rothmann was the royal spokesman. The nine-member leadership council for the Anabaptist Kingdom comprised four foreigners (one of whom was King), four Munster natives, and one (Rothmann) who fit into both categories.31

Beuckelszoon’s Court was draped in fine garments of velvet and much gold and jewels. It was regalia as if designed by critics of monarchy, in the midst of siege and privation, with insult heaped upon injury by the fact that much of what Beuckelszoon and his associates wore had been expropriated from the population that was now going hungry. There does seem to have been some awareness that this situation created dangers for Beuckelszoon, but he had an answer: “Once the King, along with his Queen”, Diewer, the widow of Matthys and primus inter pares among his wives, “and all the King’s and the Queen’s servants had decked themselves out, they had it proclaimed to the common folk in the preaching that no one should get angry … because God had selected [Beuckelszoon and his retinue] for this and set them in their estate, and everyone should stick to the estate that was their calling”.32 Then there were the gifts, such as when “King Jan”, after he declared a general amnesty, held a great feast on 13 October 1534 on the Dom Platz (Cathedral Square), which by this time had been renamed “Mount Zion”. Thousands of people attended and were fed, admittedly with food paid for with money stolen from them.33 The will of God, periodic inducements (far less as the siege went on), and promises about the next life in exchange for their loyalty to Beuckelszoon’s regime in this life were the mechanisms by which the Anabaptist regime sought—and largely succeeded—in dampening down any tendency to populist fury.

THE MISSIONARY EFFORT

The last quarter of 1534 was devoted by the Munster Anabaptists to the missionary effort to spread their gospel, and in more concrete terms to create sister Kingdoms that would act to buffers to protect their own.

Some of the most important historical documents about the Munster regime were produced in this period, notably Rothmann’s two booklets, written in December 1534 and sent to the Netherlands for translation and distribution: Restitution, which explained the theological justification of the Munster Kingdom, and the Report on Vengeance and the Punishment of the Babylonian Abomination, which laid out the case for Christian (i.e. Anabaptist) violence against all non-believers.34

After Beuckelszoon had shown some contrition for the way he ruled at the 13 October banquette—even theatrically offering to surrender the crown—he had been reassured by Dusentschuer that God’s mission required him to stay in place and organise the preachers to spread the message.

In November 1534, a contingent of preachers, Dusentschuer among them, left the city in all directions in search of recruits. It was a disaster, not only in itself but it opened up a damaging counter-intelligence vulnerability that was duly exploited. All the preachers reached their assigned locations—and all except one, as the Anabaptists in the besieged city had no way to know, were promptly rounded up and most of them executed.

The one exception was Heinrich Graess and he was spared because he had been turned: sent back into the city to tell Beuckelszoon about all the Anabaptists he had recruited who were coming to rescue the city, Graess then left again to supposedly go and get them—and informed the Prince-Bishop of everything he could about the situation in Munster.35

PREPARING FOR THE END

The Munster revolt illuminated, among other things, the mechanics—a critic might say the dysfunction—of the Habsburg realm. Facing a security and ideological challenge from a city in open rebellion, with its tentacles spreading into neighbouring zones and threatening the fabric of the entire Empire, the matter was left to one Prince-Bishop and such friends as he could call upon. Only after a series of meetings with an expanding list of states and principalities was the Empire as such drawn in.36

In December 1534, at long last, the Empire, in its languid way, finally stepped in to help Prince-Bishop Waldeck, with a meeting in Koblenz voting to send Imperial troops to finish with the Anabaptist commune. In January 1535, command of the Munster siege was transferred to the Count of Limburg and Falckenstein, Wirich von Daun, a reliable soldier just back from the front against the Ottoman-Islamic Empire,37 the threat from which formed the apocalyptic backdrop in Europe in the early years of the Reformation that gave sects like the Anabaptists more purchase than they otherwise might have had.

Anticipating the final showdown, Beuckelszoon issued a Letter of Articles on 2 January 1535 that instructed “true Israelites” on the proper way to behave in battle. The document removes all doubt about the ambitions of the Anabaptist Kingdom. Some later historians argued that the idea the Anabaptists’ Munster regime was intended as a transnational enterprise was part of the Prince-Bishop’s propaganda to rally support for himself from neighbouring Princes, but Article One states plainly: “Only those governments that orient themselves by the Word of God [i.e. Anabaptism] shall be preserved”. Showing that the use of women by extremist groups is not a new phenomenon, the Anabaptist regime recruited at least fifty women into its armed forces. By February 1525, the somewhat porous siege of the last year was tightened and starvation began to set in. Famine had been avoided to that point by the meagre but important channels to the outside world; all such channels were cut off by April 1525.38

As the paranoia and desperation of the regime worsened, there were further “executions”, including of Clas Nordhorn, beheaded by Beuckelszoon personally after he confessed under torture to volunteering his services to the Prince Bishop (it might even be true). In total, about eighty people were “executed” during the sixteen-month Anabaptist rule in Munster. Still, Beuckelszoon did not try to stop those who wanted to flee. The problem was that after the first wave of refugees found themselves butchered and displayed on pikes outside the city walls, it seemed less dangerous to stay and risk death from starvation.39

NEWS FROM THE NETHERLANDS

In the midst of all this, in the evening of 10 May 1525, an Anabaptist insurrection broke out in Amsterdam (Wederdopersoproer) and forty or so rebels occupied city hall. The rebels appealed for a mass rising, and were largely ignored. This event helped cement the Anabaptist reputation for sedition and extremism. It also foreshadowed the closing scenes in Munster: the rebellion was crushed without pity on 11 May, killing about fifty people in total (half of them state militiamen); the mayor, Peter Colijn, was restored to office; and the rebel leaders were captured and hideously executed, their hearts cut from their chests and their corpses drawn, quartered, and displayed.40

ENDGAME IN MUNSTER

Some accounts of the end of the Anabaptist Kingdom in Munster report this as happening because the commune was “betrayed from within”, which is not quite right, or at any rate is not the complete picture. The Catholic-led forces knew where to assault the Anabaptist fortress because of assistance from Heinrich Gresbeck and Hans von der Langenstrate, who fled from Munster on the evening of 23 May 1535 and were not killed like the other refugees because they provided intelligence about the weaknesses in the Anabaptists’ defences.

It is quite difficult to label Gresbeck a traitor and nor was he “within” by this time. Gresbeck, a Roman Catholic, had worked as a joiner in Munster and left his city in 1530 in search of work, which he found partly as a mercenary abroad. Gresbeck had returned to Munster in February 1534 to protect his mother’s house from confiscation. Gresbeck had dissimulated, accepting baptism from the millenarians, yet never had any sympathy with the movement.41 A city native who did what he had to during a foreign-led occupation by fanatics he despised cannot really be said to be a traitor or deserter.

Langenstrate, on the other hand, is something more like a traitor, though even he really doesn’t ever seem to have had any ultimate loyalty to the Anabaptist cause. A landsknecht, Langenstrate had fought for Bishop Waldeck’s army before defecting to become a bodyguard for Beuckelszoon, and then defecting again back to the Bishop’s forces in exchange for a promise of a cut of the war booty once the city was recaptured. There is a receipt showing Langenstrate received his cut in December 1536; he died very shortly after that.42

Both Gresbeck and Langenstrate took part in the storming of the city on the night of 24 June 1535, into the early morning of 25 June. Gresbeck swam across the moat at Cross Gate under cover of darkness with a foot bridge, allowing the Catholic troops to kill the sentries and get 300 men inside before the Anabaptists closed the gates. After awful street fighting, Beuckelszoon tried to sue for peace and safe exit for at least him and his inner circle. Instead, the landsknecht poured into the defeated city through the Jüdenfeld Gate and massacred between six-hundred and eight-hundred Anabaptists.43

Prince-Bishop Waldeck entered the city on 29 June 1535, though his moment of triumph was short-lived as he soon faced a mutiny over payment from the landsknechts, dissatisfied with the smallness of the war spoils available.44

The Anabaptist Chancellor Heinrich Krechting led a rear-guard action with about two-dozen others, barricading themselves in the market on 25 June. In exchange for laying down arms, Krechting and his men were given safe passage out of the city later that day, and he took the embers of millennialist Anabaptism with him into exile.45

AFTERMATH

Munster, a thorn in the side of the Catholic Empire even before the charismatic radicals displaced the Lutheran Reformers, was swiftly and ruthlessly re-Catholicised. One of the first acts of the restored Imperial authority was dealing with the Anabaptist rebel leaders, for whom there would be no mercy. This was not a controversial proposition, despite the religious divisions within the city, and between it and the principalities around it: both Catholics and Lutherans had an interest in making an example of the Anabaptist insurgents.

On 7 July 1535, several of the Anabaptist women, among them the Queen, were executed; generally the Anabaptist women were spared.46

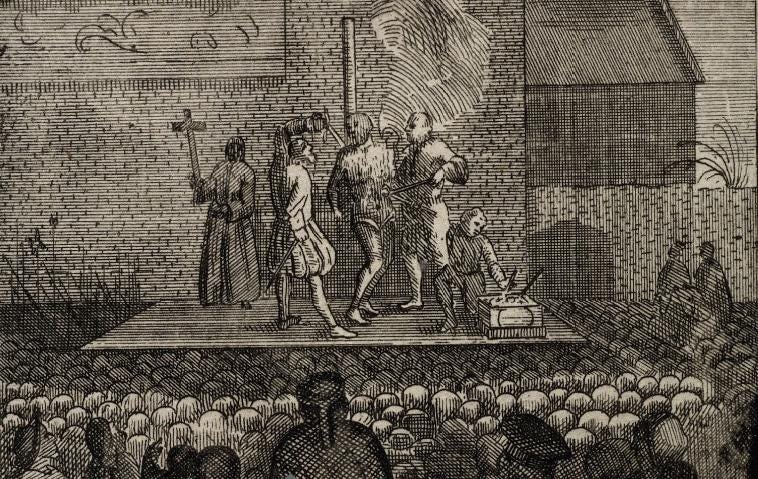

The major demonstration was the torture and execution of Beuckelszoon, Knipperdolling, and Bernhard Krechting in the Munster Prinzipalmarkt (principal marketplace) on 22 January 1536. The three prisoners were “chained to a post and made to wear spiked collars which dug into their necks as the skin [and ultimately their tongues were] ripped from their bodies with hot iron tongs. The torture lasted for a full hour as the executioners picked flesh from their bodies while being careful to keep the men alive and conscious throughout the ordeal. The idea behind this torture was that the pain endured by the body would be enough for the soul to recant so that the men were not cast into an eternal hell. They were finally executed by a dagger to the heart”. Knipperdolling, seeing this process applied to Beuckelszoon, tried to pre-empt it by choking himself to death with the collar. The executioner simply tied him down more tightly so he was unable to move.

After the men were dead, their bodies were put in cages and left to rot, hanging from the steeple of St. Lambert’s Church, a warning to all who would defy the Roman Church. The bones were removed from the cages about a half-century later, but the cages still hang from St. Lambert’s to this day. After the original tower of St. Lambert’s was demolished in 1800, it was rebuilt and the cages were put back. A direct hit from a Royal Air Force bombing raid on 18 November 1944 knocked down and damaged two of the cages, which were repaired and rehung when the church was fixed up in 1948.

The Munster experience was quickly written about, and its legacy was a lasting one. Merten de Keyser (d. 1536), the first French publisher of translations of the English Bible and the work of William Tyndale (d. 1536) and other English Protestants, produced a book just months after the regime went down in the summer of 1535.47 Gresbeck is the only person to set down eyewitness testimony to the events in Munster, writing about a decade afterwards, though his writings had no effect at all on the discourse around the Anabaptists in the sixteenth century: his work was only rediscovered and published in the nineteenth century, in 1853 to be exact.48 Gresbeck’s account has a clear purpose—to vindicate his decision to help the Catholic troops suppress the Munster Anabaptists—and as such it is open to historical challenge. The only other book that could lay claim to being by an eyewitness was published twenty years after Gresbeck’s, by Herman von Kerssenbrock, who had been in Munster as a child until the expulsion at the end of February 1534, when his Catholic parents left the city. In fact, however, though Kerssenbrock’s account is clearly coloured by his dislike of the Anabaptists, he does not rely on claims of first-hand experience. The book is a scholarly one in tone and intent, relying on primary documents in the main, including letters between the Anabaptist leaders and Prince-Bishop Waldeck.

The Munster experience had a dual legacy: on the one hand, it converted the Anabaptists into peaceable and indeed industrious schismatics, with their descendants including the Amish, Hutterites, and Mennonites, and on the other hand it left a stain that non-Anabaptists could not—and/or would not—let go of, hence the great controversy for larger Protestant sects like Baptists and Quakers over claims that they partly derive from, or are influenced by, the Anabaptists. “Anabaptist” became a generic term of abuse throughout the Reformation for anything that seemed too radical and the long memory of the terrifying experience in Munster led to inoffensive Anabaptists being harried and killed by popular outpourings and state authorities throughout Christendom for decades afterwards.49 The persecution of the Anabaptists in the Old World long after the collapse of the Munster commune is why, by the mid-seventeenth century, such a large proportion of them had emigrated to the New World.

A MODERN PARALLEL?

Final thought: a few years ago, the Munster events were raised as a parallel to the Islamic State (ISIS), though the argument was threadbare about what connected these two episodes separated by half-a-millennium, a geographic continent, and the borders of a civilisation. To the extent it was suggested the two share an apocalyptic mindset, this is actively misleading.

Nonetheless, the parallel does have some validity in this sense: while talk of an “Islamic Reformation” is in the category of the not-even-wrong—it is simply meaningless to speak of such a thing in reference to a different civilisation that will not track Christian history—one can say that some of the same processes that were active in the Reformation are now at work in Islamdom. Two stand out.

Firstly, the Wahhabist/Salafist roots of ISIS’s theological-interpretive approach place a great emphasis on the scripture, on literalism, and on stripping away custom and practice that have accumulated across the centuries in order to “purify” the faith, and this mirrors the Protestant approach. Second, an explosion in literacy and the dissemination of information. Just as the Protestant Reformation will forever be associated with the printing press, jihadi-Salafism could not exist as it does now, as one of (if not the) fasted growing Islamic currents, without the internet.

ISIS, then, in establishing a revolutionary state based on a literalist interpretation of scriptures, attracting to itself layers of supporters that include the newly literate and foreign converts, alongside more weighty intellectuals, and trying to export its revolution, only to provoke the alignment of essentially warring parties against it, can be said to have echoes of the Anabaptist regime in Munster.

The most interesting thought experiment is whether the aftermaths will have any parallels. The Munster Anabaptists not only clipped their own wings but provided a cautionary tale that shaped the Protestant Reformers ever-afterwards as they sought to right the wrongs inflicted by the Roman Church. Whether ISIS, as memory and symbol, can serve the same role in restraining future radicals seeking change in the unjust situation of the modern Middle East, by mentally closing off certain paths known to end in destruction, at least if taken to their endpoint, time will tell.

The original post can be found here.

REFERENCES

Diarmaid MacCulloch (2009), A History of Christianity, p. 622.

MacCulloch, A History of Christianity, pp. 622-3.

MacCulloch, A History of Christianity, pp. 623-4.

Hoffman had been imprisoned as a revolutionary after his theological views turned apocalyptic. Claiming theological descent from the great proto-Protestant Czech priest Jan Hus, who had been burned alive by the Roman Church in the centre of Prague for his heresy in 1415, Hoffman said the End of Days would take place in 1533 and begin in Strasbourg. It was two of his followers—Matthys and Jan Beuckelszoon—who led the Munster rebellion in 1534, believing that Hoffman had been right in general and wrong in the specifics of time and place.

Gergely Juhász (2014), Translating Resurrection: The Debate Between William Tyndale and George Joye in Its Historical and Theological Context, p. 281.

Paul Ham (2018), New Jerusalem: The Short Life and Terrible Death of Christendom’s Most Defiant Sect.

Beuckelszoon is variously known as Jan Bockelson, John Matthisson, John van Leiden, or John of Leiden.

Hermann von Kerssenbrock (2007), Narrative of the Anabaptist Madness: The Overthrow of Munster, the Famous Metropolis of Westphalia, pp. 531-2.

Kerssenbrock, Narrative of the Anabaptist Madness, p. 532.

Tom Holland (2019), Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind, p. 517.

Juhász, Translating Resurrection, p. 281.

Kerssenbrock, Narrative of the Anabaptist Madness, p. 534.

John Roth and James Stayer [eds.] (2011), A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, p. 242.

In Judges 7, Gideon, one of the Old Testament prophets, is faced with a host of Midianites surrounding Israel from the north, and God whittles down Gideon’s army—sending home the 22,000 who are “fearful and afraid” and another 9,700 who drink incorrectly from a river—until it is just 300 men left, before sending them out to defeat the Midianites. God explains that there had to be this imbalance in the forces “lest Israel vaunt themselves against me, saying, ‘Mine own hand hath saved me’,” i.e. it had to be clear that the victory was God’s work not man’s. (Earlier in the Bible, in Numbers 31, it is the Midianites who are the victims of one of the most atrocious episodes: after Moses’ armies defeat the Midianites and massacre every adult male, enslaving everyone else, God causes a plague to break out among the Israelites because he had demanded that the Midianites be annihilated entirely. Moses tells his troops to “kill every male among the little ones, and kill every woman that hath known man by lying with him. But all the women children, that have not known a man by lying with him, keep alive for yourselves” (Numbers 31:17-18). This massacre is carried out and then the concubines and livestock are divided up between “the Lord’s tribute” and the Israelites.)

Kerssenbrock, Narrative of the Anabaptist Madness, p. 538.

Juhász, Translating Resurrection, p. 281.

Roth and Stayer, A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, pp. 238-9.

Roth and Stayer, A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, p. 240.

Von Ranke, History of the Reformation in Germany, p. 437.

J. Denny Weaver (1987), Becoming Anabaptist: The Origin and Significance of Sixteenth-Century Anabaptism, p. 89; Roth and Stayer, A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, p. 241.

Roth and Stayer, A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, p. 244

Leopold von Ranke (1857, translated to English in 1905), History of the Reformation in Germany, p. 437, available here.

MacCulloch, A History of Christianity, p. 624.

Von Ranke, History of the Reformation in Germany, p. 437.

Von Ranke, History of the Reformation in Germany, p. 437.

Roth and Stayer, A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, p. 242.

This was not entirely unprecedented in the short history of the Anabaptist movement. On a much smaller scale a few years earlier in Lautern, near Blaubeuren, an Anabaptist leader named Augustin Bader “became convinced he was a prophet, inspired by the apocalyptic theology of Hans Hut”, an Anabaptist preacher in southern Germany who died (it seems genuinely accidentally from asphyxiation during a fire) while in prison in December 1527, “and the Jewish Kabbalah. In a mill at Läutern …, Bader gathered a handful of followers, proclaimed his infant son the new Messiah, and had robes and golden ornaments made to reflect this kingly status.” Beuckelszoon was thus not an innovator in this matter.

Juhász, Translating Resurrection, p. 281.

Roth and Stayer, A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, pp. 242-3.

Richard Heath (1895), Anabaptism: From Its Rise at Zwickau to Its Fall at Münster 1521-1536, p. 195.

Christopher Mackay [translator and editor] (2016), False Prophets and Preachers: Henry Gresbeck’s Account of the Anabaptist Kingdom of Münster; Roth and Stayer, A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, pp. 243-4.

Mackay, False Prophets and Preachers.

Heath, Anabaptism, pp. 159-160.

Roth and Stayer, A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, pp. 245-6.

Roth and Stayer, A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, pp. 245-6.

Von Ranke, History of the Reformation in Germany, pp. 439-40.

Roth and Stayer, A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, p. 242.

Roth and Stayer, A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, pp. 246-7.

Roth and Stayer, A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, pp. 247-9.

Charles Caspers and Peter Jan Margry (2019), The Miracle of Amsterdam: Biography of a Contested Devotion.

Heath, Anabaptism, pp. 159-160.

Peter G. Bietenholz and Thomas Brian Deutscher [eds.] (2003), Contemporaries of Erasmus: A Biographical Register of the Renaissance and Reformation, Volumes 1-3, p. 417.

For the 600 estimate, see: Roth and Stayer, A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, p. 249. For the 800 estimate, see: Michael Clodfelter (2017, 4th ed.), Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015, p. 14.

Roth and Stayer, A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, p. 249.

Based in Lingen after the fall of Munster, Krechting tried to reignite the cause and in 1538 found himself the undisputed leader of the radical wing of the Anabaptists after Jan van Batenburg was executed that February, two years to the month after the Munster rebel leaders were put to death. The “Batenburgers”, largely confined to the Netherlands, were known as the Zwaardgeesten (sword-minded) by their critics, which included most Anabaptists by this point, disillusioned with revolution on earth after the Munster experience. The Duchy of Oldenburg, where the radical Anabaptists were sheltering under the tolerance of Count Anton, was defeated in war by the Bishopric of Munster later in 1538 and all efforts to re-do Munster by seizing direct power fizzled when there was no popular reaction to Krechting’s moves toward rebellion. Krechting more or less drops out of history after that, though seems to have undergone a change in views, dying as a man of status in 1580 and his descendants went on to be part of the political elite in Bremen.

Roth and Stayer, A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521-1700, p. 249.

Juhász, Translating Resurrection, p. 282.

Mackay, False Prophets and Preachers.

MacCulloch, A History of Christianity, p. 624.

To "sally forth" was not a comic phrase in sieges of the 16c. Mattys's sally was certainly an ill-planned disaster, the sort of dark comedy that we moderns imagine when we use the phrase. This was an excellent essay.