Where Did Islam Come From?

Assessing the historical claims and arguments in ‘The Sacred City’ (2016), by Dan Gibson

In 2016, the Canadian author Dan Gibson released a film, The Sacred City, which challenged the traditional story of Islam’s beginnings. Gibson’s primary argument is that the ka’ba, the sacral centre of the faith, was not always at modern Mecca, deep in the Hijaz region of central Arabia, but was originally located much further north, in the Levant, specifically in what is now Jordan. In this post, I will give an overview and assessment of this aspect of Gibson’s film. In a subsequent post, I will look at the theories in the last part of the film about how and why Islamic history on the ka’ba developed.

GIBSON’S CASE ON ‘THE SACRED CITY’

Gibson begins with there only being one mention of “Mecca” in the Qur’an. Muslim scholars and historians associate other Qur’anic terms with the city, notably “Becca” (or “Bakka”), which is treated as a synonym. What Gibson translates as the “Holy House” (al-Bayt al-Haram), the ka’ba, is assumed by Muslims to have always stood in Mecca, with the “Forbidden Gathering Place” (al-Masjid al-Haram) being the sacred zone surrounding it. The problem, says Gibson, is that the text of the Qur’an gives no reason to associate any of these terms with Mecca or the Hijaz.

The Prophet Muhammad is said to have had the first of the revelations that became the Qur’an in 610 AD and to have died in 632. Islamic historiography presents Mecca in the period preceding the Arab conquests as a bustling metropolis, a key stop on the trade route between Syria and Yemen, and its ka’ba as a focus for pagan pilgrims. Islamic records say that the umra, the “lesser” pilgrimage, predates Islam.1 “Al-Haram”—the “Forbidden”—refers to the fact that violence and killing, even of animals, was banned in the sanctuary space, usually marked out with stones, around a pagan shrine or temple, which was often located in a valley or remote desert. The Forbidden Gathering Place was, so Muslim history says, one of the few places the otherwise fractious Arab tribes united.2

In Gibson’s telling, there is no archaeological record in Mecca before 800 AD. Everywhere in the Arab world, says Gibson, when construction projects begin, somebody from the ministry of antiquities is present at the digging of the foundations because of the likelihood artifacts will be discovered. Mecca—despite Muslim belief it was the “Mother of All Cities” at the time of the Prophet, surrounded by great walls and containing many temples—has seen nothing like this, according to Gibson.

From the Qur’an, says Gibson, we get a picture of Muhammad being born in a reasonable-size city, able to raise men for caravans, and, crucially, the setting is an agricultural one. The earliest surviving biography of Muhammad, says Gibson, refers to the Prophet’s birthplace as one where there are grasses and grapes and trees: this is not Mecca. Gibson makes much of his study of ancient maps, and the fact Mecca is on none of them, an oddity if it was such an important economic and social locale.

This sets Gibson up for his main question: Are Muslims “facing the wrong direction when they pray”? He clearly thinks so, and says that the clues about the original location of al-Masjid al-Haram can be found within the Islamic canon.

The qibla (direction of prayer) is a significant part of Gibson’s focus and evidence. That there was a change in the qibla is undisputed in the fabric of Islam’s sacred history. He quotes the Qur’an reference to a change in the qibla (2:142-144):

The foolish among the people will say, “What has turned them away from their qibla which they were upon?” Say, “To Allah belong the east and the west; He guides whom He wills to a straight path.”

And thus We made you a middle umma [community], that you may be witnesses over mankind, and the Messenger be a witness over you. And We did not make the qibla which you were upon except that We might distinguish who follows the Messenger from who turns back on his heels. And indeed, it was surely burdensome [as a test], save for those whom Allah guided. And Allah would not be one to let your faith go to waste. Indeed, Allah is to the people Compassionate, Merciful.

Indeed, We see the turning of your face in the sky, so We will surely turn you to a qibla that you will be pleased with. So turn your face toward al-Masjid al-Haram, and wherever you are, turn your faces toward it. And indeed, those who were given the Book surely know that it is the truth from their Lord. And Allah is not unaware of what they do.

As Gibson notes, the original qibla location is not mentioned at all and the new location given only as “al-Masjid al-Haram”.

Muslim belief is that the Prophet changed the qibla from Jerusalem to the Hijazi Mecca in 623 AD, about a year-and-a-half after the exodus (hijra) of the early Muslim umma from Mecca to Medina. But, Gibson points out, this comes from much later sources, giving an example from the Hadith, the sayings and activities of the Prophet and the Companions (Sahaba), recorded by Al-Bukhari:

The Prophet prayed facing Bayt al-Maqdis [the Pure House, understood by Tradition to mean Jerusalem] for sixteen or seventeen months [after arriving in Medina] but he wished that his qibla would be the Ka’ba. … A man from among those who had prayed with him, went out and passed by some people offering prayer in another mosque, and they were in the state of bowing. He said, “I testify that I have prayed with the Prophet facing Mecca.” Hearing that, they turned their faces to the Ka’ba while they were still bowing.

This change of direction mid-prayer supposedly happened at the Mosque of the Two Qiblas (Masjid al-Qiblatayn) in Medina. Gibson says that when this mosque was stripped down in 1987, the original qibla wall—the one worshippers face in prayer—was indeed found to point north. Using GPS technology, Gibson tests where the original qibla walls for ten other early mosques face. The mosques date, he says, from 623 to 724 AD, and all-but one are spread throughout the Middle East.3 The one exception, interestingly, is in China, the Huaisheng Mosque in Guangzhou, which the film claims was constructed in 627 AD.4

In the words of the voiceover, the qibla directions of these eleven mosques “point to just one place”: Petra, in the south of what is now Jordan.

In building his case that Petra was the original location of al-Masjid al-Haram, Gibson pursues several lines of evidence. He begins by arguing that Becca/Bakka means “weeping”, and this was applied to Petra as it was a place of sadness due to persistent earthquakes. There was a particularly devastating earthquake in the Levant in 551 AD, heavily damaging Petra: recovery would have been ongoing twenty years later when Muhammad was born, says Gibson.

Gibson points out that Islamic history itself documents the Abbasids—the dynasty that seized the Arab Empire in 750 AD—being resident in, and coordinating their conspiracy against the Umayyads from, Humayma, twenty-five miles south of Petra.5 As the Abbasid claim to power was based prominently on their lineage, as descendants of the Prophet and the Quraysh, a tribe Islamic history identifies as based in Mecca, it is a noteworthy detail.6

Gibson next looks at a story in the earliest surviving biography of the Prophet. Abdullah, Muhammad’s father, came home from working in the field and asked his first wife to lie with him; she refused because he was dirty. He cleaned himself up and went to his second wife, with whom he conceived Muhammad. The interest for Gibson is that the narratives all use the same word for the substance Abdullah was caked in: teen (طين), which he translates as “heavy soil” (could also be “clay”). The point is it is a rich and moist substance found on cultivatable land, of which the Hijazi Mecca had none,7 while Petra was watered by aqueducts and thick with trees, fields, fruit, and gardens. Gibson says the biography additionally makes reference to the sacred city having walls, which Petra did and Mecca did not.

Marwa and Safa are described in Islamic sources as “mountains” in Mecca that believers are supposed to travel between seven times, and Al-Bukhari (d. 870), the Hadith scholar par excellence, says Muhammad did this in a rainwater course between the two, according to Gibson, who argues that this tallies well with the geography of Petra—a valley where the water runs across it, rather than through it—and less well with the two small rocks identified as Marwa and Safa in the Saudi capital today, which have no rainwater course between them.

From Al-Bukhari we get the following: “The Prophet went on advancing till he reached the thaniya [mountain pass or gap] through which one would go to them [i.e., the people of Quraysh]”. In a number of other places, Al-Bukhari references Muhammad entering Mecca via “thaniya” (ثَنِيَّة). Gibson observes that the Hijazi Mecca does not have such things, but anyone who has been to Petra likely entered it through a thaniya, the famous Siq.

Another story from the earliest biography presents one of Muhammad’s earliest followers, Tufayl ibn Amr, going to Mecca, being converted to Islam, then coming home and convincing his wife to take up the new faith. She is told to go to the temple of her former deity, the Nabatean god Dushara (or Dusares or Dhu’l-Shara), to “cleanse yourself from it”, which she does in the “trickle of water from a rivulet from the mountain” that runs through the sacred sanctuary surrounding the temple.8 For Gibson, this is further evidence: streams running from mountains is more Petra than Mecca on its face, but there is no record of a temple devoted to Dushara in Mecca, while such a temple, Qasr al-Bint, is located an hour’s walk from Petra.

Taking it all together—Dushara, the vast number of other temples, the thaniya, water streams, city walls, agricultural land, trees, grass, and the qiblas—Gibson is satisfied the Islamic records about the ka’ba in the first phase of Islam point to Petra, not Mecca.

GIBSON’S ARGUMENT FOR WHEN AND HOW

The obvious next question is, if the ka’ba started out in Petra, when did it change to Mecca, and in what circumstances? Gibson’s answer is: towards the end of the Second Fitna or civil war, which Gibson says began in 683 AD when Abdallah ibn al-Zubayr declared himself Caliph in opposition to the ruling Umayyads. Ibn al-Zubayr was based in the sacred city, says Gibson. The Umayyads, naturally, sent troops to suppress the revolt, beginning with a siege, whereupon (in the words of the narrator), “Ibn al-Zubayr then did a shocking thing: he destroyed the ka’ba”. Brought the news of the sudden death of the Umayyad Caliph, the besieging forces—which included members of the ruling dynasty—departed so they could sort things out in Damascus. The new teenage Caliph only lasted forty days before he died, too.9

Surveying this story, Gibson notes that the journey from modern Mecca to Damascus is over 850 miles as the crow flies. Even making heroic assumptions about the route and a twenty-mile-per-day pace of travel, that is a 43-day journey. Adding up the time taken for the messenger to get from Damascus to Mecca with the news of the Caliph’s demise, and the time taken to decide on a retreat and operationalise it, “there is simply not enough time”, Gibson says: the boy-Caliph would have expired before Umayyad troops reached Damascus, and the Islamic sources are clear this did not happen. “Mecca is too far away to be believable”, Gibson goes on. “This problem of distances plagues Islamic history … Mecca in Saudi Arabia is simply too far removed to fit many of the stories in early Islamic history.” If the ka’ba was in Petra, the journey to and from Damascus would be about fourteen days.

Gibson turns next to Al-Tabari’s “History of the Prophets and Kings” (Ta’rikh al-Rusul wal-Muluk), one of the great works of Islamic literature, formatted as a year-by-year account dating back to creation, and a crucial source for Muslims about the early years after God’s final revelation. Gibson focuses on 70 AH (July 689-July 690 AD), a threadbare entry by Al-Tabari of just a few lines, in stark contrast to the extensive documentation for the years either side. Gibson’s argument is that “later editors censor[ed]” Al-Tabari’s Year 70, but that even what is left gives a hint at what happened.

Al-Tabari records that in 70 AH, Ibn al-Zubayr’s brother brought supplies to the rebels at the sanctuary, and what he brought was many horses and camels, seen by Gibson as useful only for moving people. Gibson contends that this was the moment where Ibn al-Zubayr took his “religious project” into high gear: granted breathing room by the lull in the war, he sought to buttress his legitimacy as caliphal claimant by rebuilding the holiest site in the Arab Empire—in Mecca, a safer location. In planting the ka’ba for the first time in the Hijaz, Ibn al-Zubayr had lost the holy city, but he was able to slightly veil this, in Gibson’s reckoning, by carrying with him the Black Stone (Hajar al-Aswad) supposedly left by Adam at the first ka’ba and placing it at the corner of his new ka’ba.

Ibn al-Zubayr was ultimately defeated and killed in 692, but Gibson believes the processes touched off by the civil war resulted in permanent changes to the ka’ba and qibla location. His theories about this will be explored in the next post.

ASSESSING THE PETRA THESIS

An obvious criticism of Gibson’s film is stylistic, namely its breathless tone. Gibson’s use of a phrase like exposing the “hidden truth about the Mecca mystery” might be forgiven—everyone has to market their work. However, when Gibson suggests he has come up with a “radical new theory” about the ka’ba’s original position, or says that “up until now no-one has ever questioned” whether it was in the Hijazi Mecca, he strays into being misleading. As anybody with an interest in this subject will immediately recognise, Gibson is following a trail blazed by the “revisionist” scholars of early Islam, such as John Wansbrough, Patricia Crone, and Gerald Hawting, who began their work in the late 1970s. By the first decade of the twenty-first century, the ossified consensus of academic Islamic Studies, which had long relied heavily on the received religious Tradition, was undone.10 Nor was Gibson the first to try to bring this scholarship to a popular audience: that was Tom Holland, about half-a-decade before Gibson’s film. The positive aspect of this for Gibson is that it means he is on firmer footing for some of his substantive claims than his critics allow. The negative is that it means he is not quite the lone maverick he makes himself out to be.

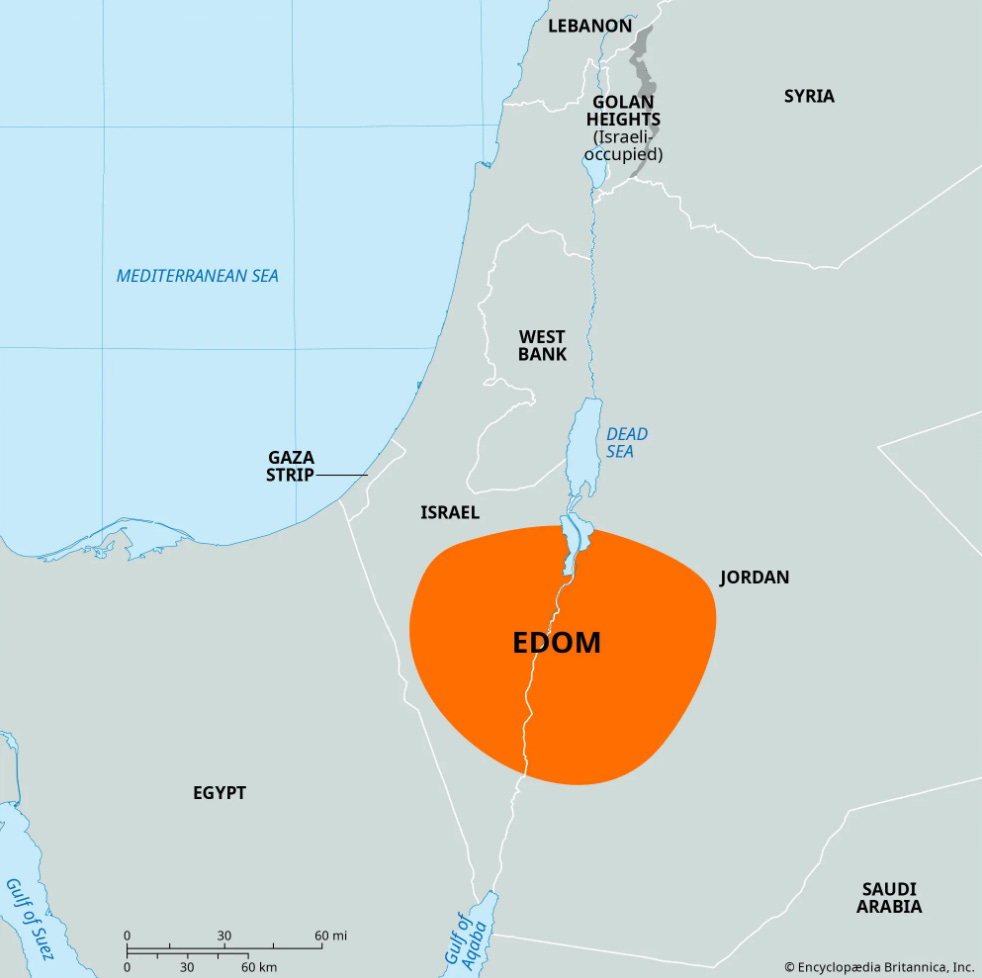

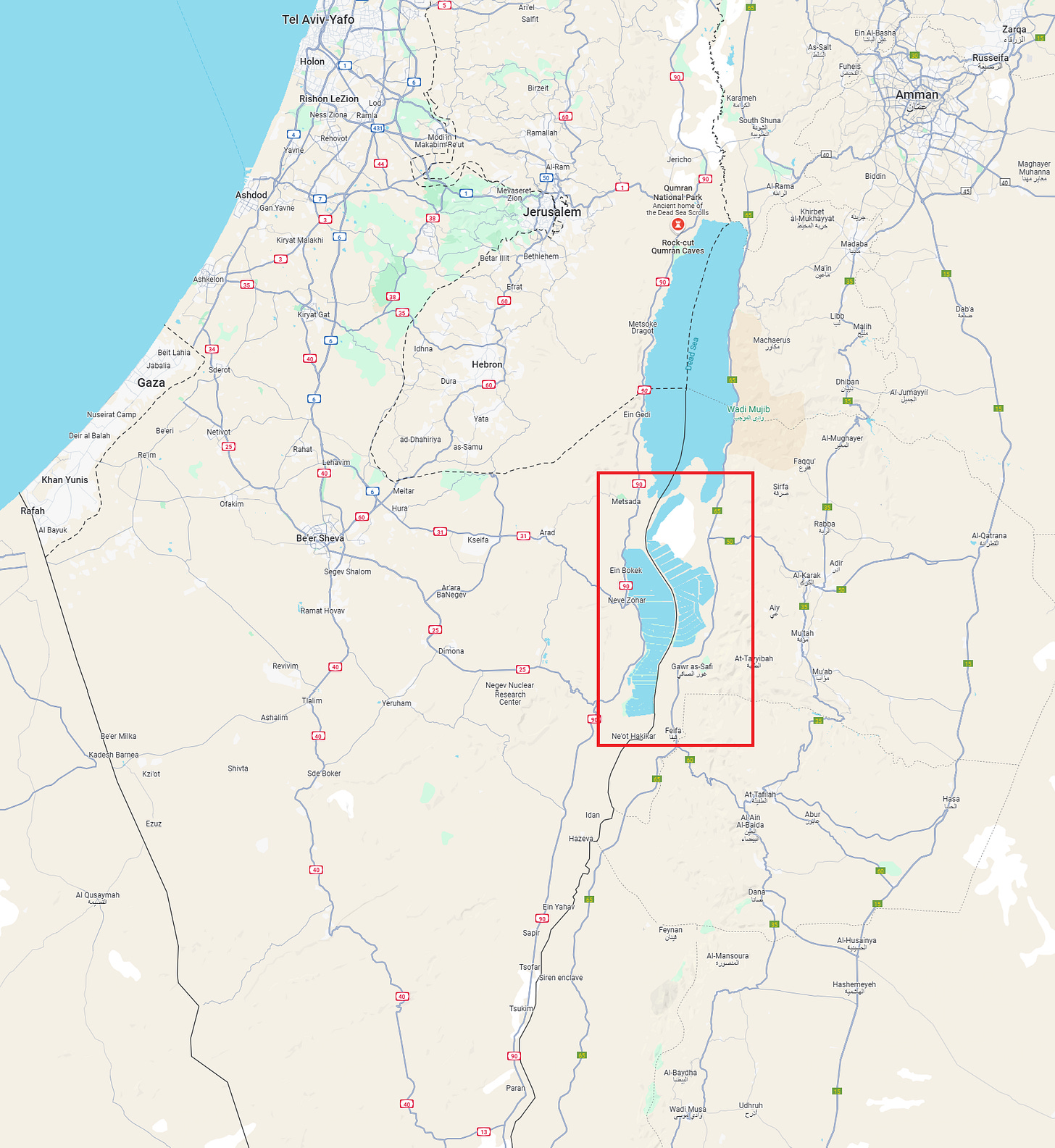

Gibson has clearly put an awful lot of work into this and he is, in my judgment, correct in the broad contours, and in some of the key details. It is overwhelmingly probable that the Sacred House (al-Bayt al-Haram), the ka’ba, and the Sacred Place of Prostration (as I would prefer to translate “al-Masjid al-Haram”), were located somewhere south of Jerusalem, roughly in the territory once known as Edom, comprising Nabataea and the Negev, what is now southern Israel and southwestern Jordan (an area which includes Petra). Gibson also lays appropriate stress on the agricultural context that is so clear in the early sources about al-Masjid al-Haram, which is critical evidence that the city under discussion cannot be the Hijazi Mecca.

Gibson’s primary weakness, however, is precisely on sourcing. Gibson has, obviously, been attacked, frequently viciously, for his arguments. There have been imputations of a sinister agenda behind Gibson’s work that seem unfair.11 The critics who have zeroed in on Gibson not being a professional historian seem to have more of a point—not in the sense of vulgar credentialism, but in terms of his skills, methodology, and assumptions. The issue is that there is no consistent approach to the Islamic sources, and the result is a muddle.

The Geography and Theology of Early “Islam”

The lack of a systematic approach to sourcing is behind the first of two extraordinary lacunae in the film: the nature of the Arab monotheism in the period Gibson is focused on. Gibson takes for granted throughout the film that Islam arose as a distinct entity that drove the conquests beginning in the 630s and formed the framework for the Arab Empire created in their wake. There is every reason to believe this is the wrong way around: that Islam is the outcome, not the cause, of the creation of the Arab Empire. Gibson seems to be unaware that this is even a debate in the scholarship.

Gibson’s view of Islam emerging ex nihilo is not unique: it derives from the faith’s own sacred history, which presents Islam emerging pristine with the Prophet and everything afterwards being a decline from this ideal.12 These Islamic accounts are the only narrative histories we have of Islam’s origins, an enormous problem for non-Muslim historians,13 and a large part of the explanation for critical scholarship being so tentative for so long.14 A common pre-1970s approach by source-critical scholars was pointing to the Qur’an’s self-evident inheritance from Jewish and Christian scripture, and positing ways that this matrix—the Levantine “sectarian milieu” of Jewish, Christian, and intermediary sects—had, as an external agent, exerted “influence” on Islam, conceived of as a discrete and coherent creed.15 Such secular sceptics generally assumed Muhammad authored the Qur’an, and, in explaining where he came by his ideas, the argument was that during his travels as a tradesmen in Syria, Muhammad encountered, usually in oral form, fragments of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, plus extra-Biblical materials and folkloric teachings, which were then amalgamated into the Qur’an.

The inadequacy of this explanation for the Qur’an’s formation is evident simply by reading it. The Qur’anic monotheism is, tellingly, “non-denominational”: it draws heavily from the Tanakh and the New Testament, but merges these elements as if the Jewish-Christian “parting of the ways” had never happened. The disregard for “orthodoxy” is even more evident in the Qur’an’s use of para-Biblical and post-Biblical material, where many of the incorporated traditions, including it seems the famous Dead Sea Scrolls,16 were already ancient and largely forgotten “heresies” to Jews and Christians by the beginning of the seventh century.17 This level of familiarity with Biblical literature is too sophisticated and wide-ranging to plausibly be attributed to the Qur’an author(s)’ incidental exposure.18 The Qur’an text, rather than showing evidence of “borrowings” from the Levantine sectarian milieu by a foreign and independent confessional group, bears witness to a community from the sectarian milieu,19 immersed in its Biblical assumptions and polemical practices.20

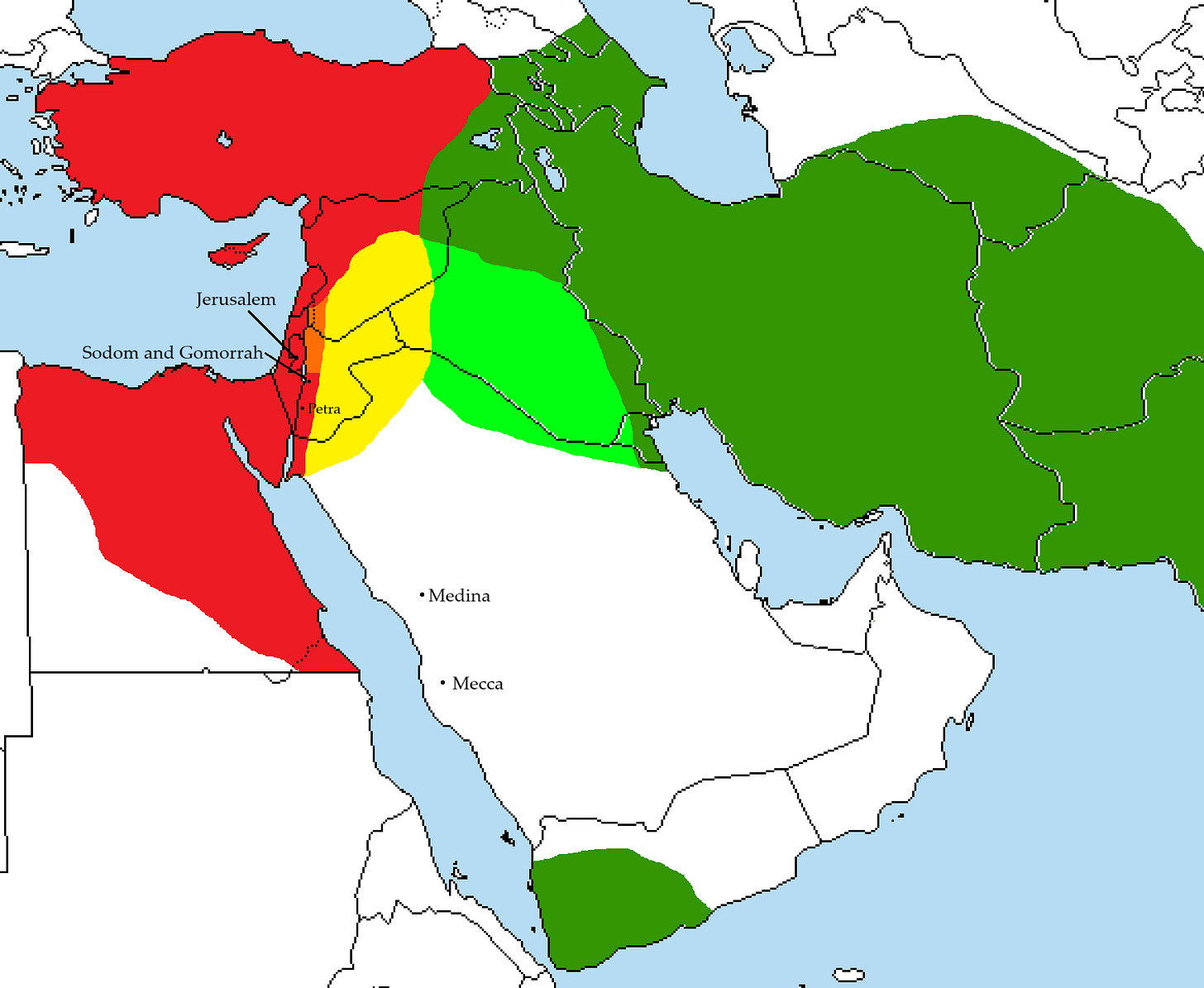

The question of how an Arab came into contact with Biblical ideas would hardly be a challenge at all if not for the Islamic Tradition, which presents a region on the eve of Islam where monotheism is confined to the Fertile Crescent and the Arabs exist in isolation from it in a wholly pagan Arabia.21 The non-Muslim sources agree about the geography of monotheism,22 but show there was a considerable Arab presence in this zone and that Arabs were no strangers to monotheism. (As we shall see, even the Qur’an shows Muhammad’s Arab opponents are Biblical monotheists.)

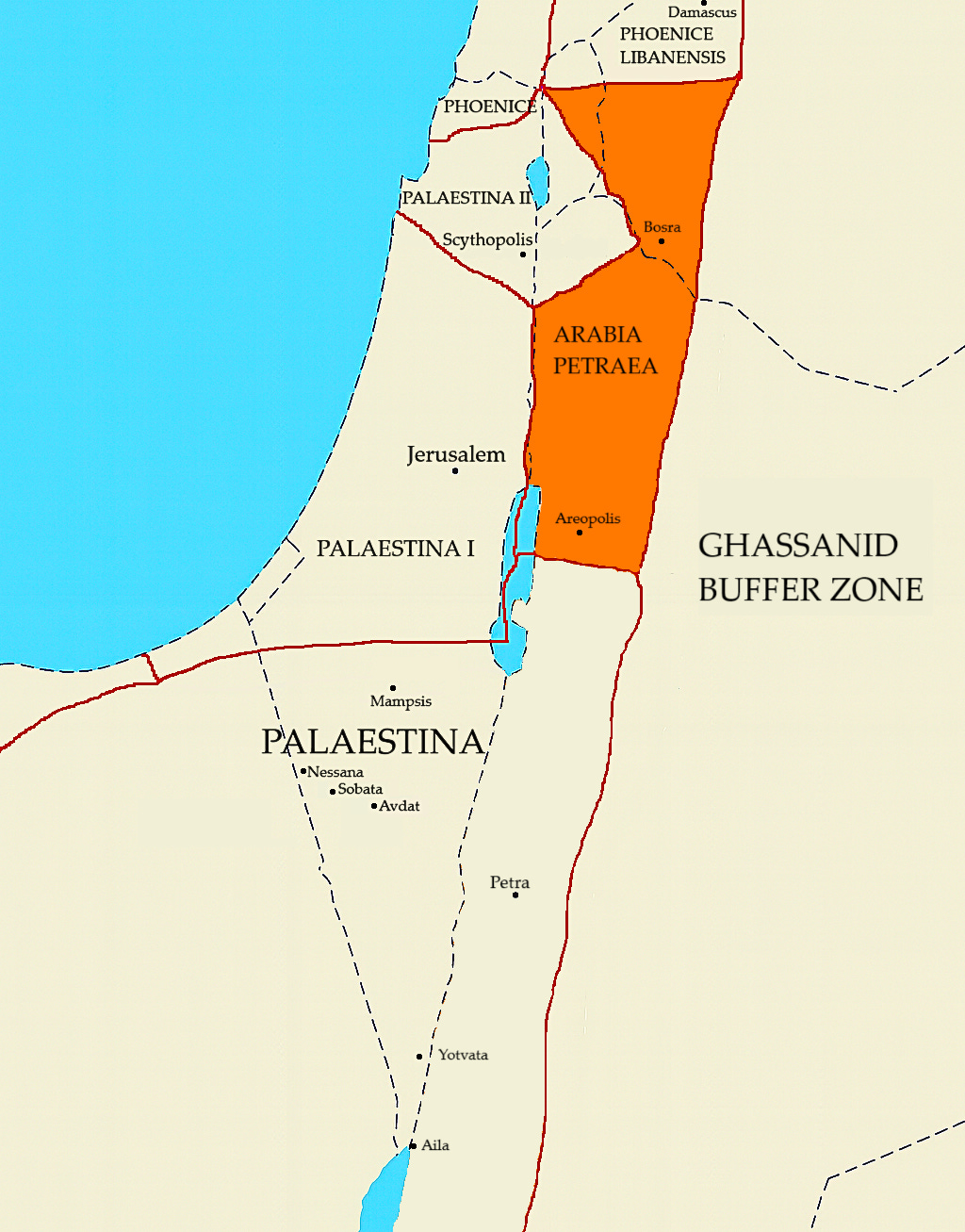

From the first decades of the fourth century AD,23 the Romans had been employing Arabs tribes as foederati, effectively mercenaries to protect the Empire’s frontiers and reinforce the legions.24 Roman gold, weapons, and military training drew nomadic Arab warbands north in significant numbers; made them more cohesive; and ultimately settled them in the Fertile Crescent, alongside the Jewish-Christian sectaries. The Arab adoption of monotheism was rapid, and the extent of the enthusiasm can be seen in it spilling back into northern Arabia.25 By the end of the fourth century, Roman policy evolved into a broader one of stabilising the periphery by allowing Barbarian foederati to settle within the Empire’s borders.26 The Ghassanid Kingdom, on paper a client buffer polity of Rome, became so integrated—especially in its devout Christianity and self-conception as the shield of God’s own realm—that in all practical senses it became part of the Empire. Indeed, by the sixth century the Ghassanid Kings exercised recognised authority over territory within the Roman frontier in Arabia Petraea, the province created from the annexed Nabatean Kingdom back in 106 AD, and many Ghassanid Arabs settled to the south and further into the interior, in parts of southern Syria that had been renamed Palaestina after the crushing of the Judean revolt.

The Roman-Persian truce reached in the aftermath of Julian the Apostate’s 363 AD invasion held, with one very brief exception, until 502, when a century of nearly continuous fighting opened. The main battlefield was the Syrian-Mesopotamian borderland between the two Empires, and the Sasanians had matched the Romans’ utilisation of the Arabs, taking suzerainty over the Lakhmid Kingdom back in the 330s. The Lakhmids, as Nestorian Christians, were slightly awkward coalition partners, but in many ways no more awkward than the Monophysite Ghassanids were for the Chalcedonian Byzantines.27 Arabs were by no means a majority on either side of the line, their numbers dwarfed by the mosaic of Jews, Greeks and other Hellenised peoples, Nabataeans, Assyrians, and Persians. But the shared Aramaic language and the variant forms of Christianity gave Arabs a place in the two quite coherent polities, and the Arabs’ military prowess made them outsize political players.

The plague that ravaged Rome and Persia in the 540s increased the relative power of the Arabs further by, on the one hand, reducing the imbalance in population between the disproportionately-affected urban Imperial heartlands and the desert periphery, and on the other hand increasing the Empires’ reliance on the Arabs for the war effort, their own manpower having been so grievously depleted. By the turn of the seventh century, austerity had forced the Romans to withdraw troops all along the border-zone of Palaestina and abandon some forts entirely.28 Large populations of hitherto unknown Arab tribes filled the vacuum. The settlers were designated foederati; it was in nobody’s interests to clarify whether they were truly friends of the Roman people or intruders being paid extortion money to take no more.29 In the Negev, south of the cluster of Nabatean towns around Avdat, Roman control was nominal, weaker in many ways than over the Ghassanid polity, and just as the distinction over the physical frontier was blurring, so in this area were the doctrinal frontiers, as the beliefs of the newcomers and older inhabitants mingled and mutated.30 In the final Roman-Persian showdown that erupted in 602, the Ghassanid and Lakhmid Kingdoms fell apart and when the guns fell silent in 628 the two exhausted superpowers were able neither to pay their former Arab clients nor resist them when they moved in to take for themselves.31

In sum, when looking at the mystery of how the developed Biblical monotheism of the Levant reached Muhammad in the seventh century, the starting point for orienting oneself is realising that the existence of the mystery is the problem. The geography is not at issue: the foundations of a creed as steeped in Biblical lore as Islam are securely located outside Arabia, in the Levant, specifically in and around Roman Syria.32 The mystery of Islam’s Meccan origins, on inspection, turns out to be part of the creed,33 a theologically inspired back-projection that is designed to be mysterious. An Arabian setting for the origins of Islam, a central guiding premise of the Tradition,34 puts a thousand miles of sand between the Prophet and the centres of monotheism: it insulates him from charges of fraud or imitation, and proves that Islam’s origins must be miraculous.35 An illiterate merchant proclaiming Biblically-complex prophecies in a pagan Hijaz does indeed seem to require a divine explanation. A Biblical holy man in the vicinity of Syria in Late Antiquity borders on cliché.36

Significant parts of the Qur’an are “ambiguous”, as no less a source than the Qur’an acknowledges.37 The Islamic Tradition that developed purports to tackle this problem: the biographies of the Prophet (Sira), the Maghazi literature on the military campaigns of the 620s-30s,38 the Hadith collections, the legal texts that went into developing the shari’a (Holy Law), apologetic works, and theological arguments (kalam). These various literary elements themselves imposed interpretations onto the Qur’an text that gained popular currency, and they formed the basis for explicit exegesis (tafsir) on God’s Word. Gibson treats the Qur’an and the Tradition as equivalent sources, a methodologically incoherent thing to do, since Tradition generally creates more of the past than it preserves.39 In the Islamic case, the glaring problem is that almost nothing in the extant Tradition corpus predates the ninth century,40 and the issues only multiply when it is factored in that virtually all of this theological scaffolding for emergent Islam was formulated in Mesopotamia,41 much of it by converts from among the conquered peoples, especially Persians and Jews.42

Muslim belief is that the Qur’an was revealed piecemeal to Muhammad during his lifetime by the Angel Gabriel.43 A major part of the tafsir is “occasions of revelation” (asbab al-nuzul) literature,44 which provided context and meaning to aya (verses) of the Qur’an that are often devoid of both, creating a rich profile of the Prophet and chronology of his career.45 Oftentimes, however, it is clear the explanations given by Muslim scholars for Qur’anic passages are based on no secure knowledge or even historical memory—that the Qur’an text and the exegesis are, so to speak, free floating, and their pairings effectively arbitrary.46 Whole battles and other events in the Sira look suspiciously like inventions to give a backstory to a Qur’anic aya, and the whole chronology is marred by “telltale signs of having been shaped by a concern for numerological symbolism”.47 In some cases, the exegetes confess bluntly to being baffled by the Qur’anic text they nevertheless supply a meaning to, complete with historical context, geographical setting, names of previously anonymous protagonists, and the rest of it.48 It is this accumulated Tradition, which tells us a great deal about Muslims in the late eighth and ninth centuries AD and little about Muhammad’s community in the seventh century, that has to be stripped away so the Qur’an can be read on its own terms.

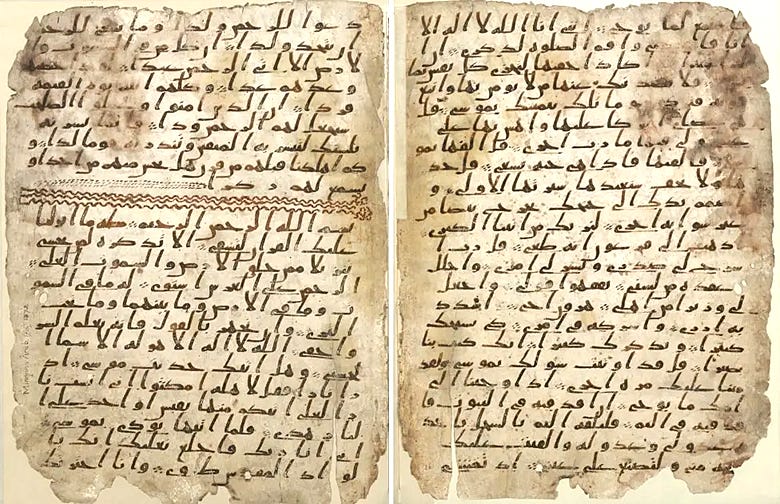

Now, using the Qur’an as a source for the Muhammadan and early conquest phases is not without problems. Nobody knows where, when, or how the Qur’an was canonised, nor even such basic details as what language it was first written in.49 The Tradition narrative, of an oral Qur’an that was stabilised in writing by the Caliph Uthman in 653 AD,50 is a just-so story where the question is what it conceals.51 One answer, most associated with Wansbrough, is that the Qur’an was codified simultaneous with the production of the Tradition in the ninth century, even if elements existed in some form earlier.52 Wansbrough documented the remarkable absence of jurisprudence derived from the Qur’an,53 and some shari’a ordinances contradicting Qur’anic prescriptions.54 The silence before the early eighth century about the Qur’an, in textual sources and inscriptions, is deafening.55

For all that, there is enough physical evidence to consider the late-codification theory highly unlikely, if not decisively overthrown. The consensus that the Qur’an is authentically Late Antique is reinforced by the failure of three generations of revisionists to find a hint of anachronism in its text.56 The very process of the exegetical Tradition gives strong evidence that the Qur’an originates early: what the Islamic scholars did was try to make sense of text that had come down to them, which they dared not alter, despite it confusing them, because they believed it to be the Word of God.57 If the Qur’an was of late origins, one would expect it to be less awkward from the standpoint of what became Islamic orthodoxy. That the Qur’an was preserved so carefully, and bears the stamp of its origins in Muhammad’s lifetime, makes it usable as a source, a precious speck of light amid the near-impenetrable darkness of Islam’s origins.

If one does what Gibson neglects to do and sift the sources to try to get back behind the later Tradition, what one finds in the Qur’an above all is an emphasis on strict monotheism within a Biblical universe. Another major Qur’anic theme is the imminence of the Day of Judgment, where unbelievers will be physically destroyed on earth and then consigned to Hellfire.58 Muhammad regularly threatens his opponents on this score, and they are shown taunting him because it has not happened.59 A correct understanding of angels’ place in God’s cosmos and the reality of resurrection round out the major Qur’anic propositions.

Muhammad in the Qur’an is a continuation of the line of Hebrew Prophets and Jesus.60 The Qur’an does differentiate its believers from Jews and Christians,61 but not in the sense of denying their scriptures come from God or categorically equating their doctrines with unbelief. “Our God and your God is One, and we are muslims [submitters] to Him”, the Qur’anic Prophet says.62 On the relatively rare occasions variants of “muslim” are used in the Qur’an, it is always like this, as a descriptor for “one who submits [to God]”, not a proper noun, and “islam” (submission) is used the same way. “Believers” (mu’mineen) is the term overwhelmingly favoured in the Qur’an for its votaries.63 The Qur’an treats Jewish and Christian traditions as a unified tapestry of divine revelations, while lamenting that some believers have lapsed into errors.64 Jews and Christians are not being called on to ‘convert’ but to ‘correct’ their beliefs, to reform and ‘return’ to the ‘true’ version of their own faith and the covenant with God that apparently existed before their partisan deviations.65 The Qur’an calls this pure and primordial doctrine Millat Ibrahim (the creed or way of Abraham).66 It is this indeterminate Biblical monotheism that Muhammad is preaching.

Abraham is the key figure in the creedal framework of the Qur’an and the identity of its believers.67 The Qur’anic denial that Abraham was a Jew or a Christian is within the paradigm adumbrated above: the claim is that he was a non-factional submitter to the One God,68 the source of the primordial creed that Muhammad believed animated all prior prophets, which he is reviving, not inventing. “I am not a novelty among Al-Rusul [the Messengers or Apostles]”, Muhammad says in the Qur’an.69 It is this Abrahamic fulcrum that made the believers’ community in the earliest phases, if not quite “ecumenical”,70 open enough to include some Jews,71 and perhaps some Christians.72 Where other monotheistic post-Roman peoples had to struggle to construct an Abrahamic lineage by appropriating the Israelite legacy,73 the Arabs’ status as a Biblical people was uncontested: they descended directly from Abraham through his son, Ishmael, born to a concubine named Hagar.74 Muhammad’s followers are better thought of as “Ishmaelites” at this stage, bearers of the ‘original’ Abrahamic creed.75

For Gibson, this would have been another line of evidence associating early “Islam” with the Levant: all traditions about Abraham and his progeny surround the Jewish and Christian Holy Land, and the whole premise underlying the ka’ba—of a sacred site with Abrahamic origins worthy of pilgrimage—derives from those two monotheisms and centres on the same place.76 The Jerusalemite area was clearly regarded by the Ishmaelites as the Holy Land, theirs by blood right,77 and it was very pointedly the first target of the conquests, part of the evidence for the more Jewish character of the Ishmaelite creed at this point.

The non-factionalism of the Qur’an’s doctrine and dominant themes reflects the sectarian milieu, where the polemical and exegetical discourse defied the frontiers of orthodoxy so painstakingly erected over preceding centuries by rabbis and bishops at the Imperial centre.78 The sects existed on a Jewish-Christian continuum, many neither distinctly one nor the other, and the sects were often difficult to tell apart from each other. On occasion, however, and over time, the process of argument, charismatic leadership, and the intervention of external events, could refine the boundaries of one sect sufficient to crystalise it into something separate from the others.79 On the grandest stage of all, this was to be the story of the Ishmaelites. The Ishmaelite sect, having developed in a more Jewish part of the milieu,80 positively enthused Jews in the 630s,81 and there was some Christian sympathy, perhaps a factor in the rapidity of the conquests.82 Once Ishmaelites moved beyond the Jerusalemite Holy Land, however, their horizons broadened: the Jewish particularism gave way to a Christian universalism, and ultimately a communal universalism that was a fusion of the two, defined against both.83

Had Gibson followed this thread, he would have recognised that his question of when the ka’ba moved was subsumed in the question of when the Ishmaelites turned to a more exclusivist monotheism. And that would have avoided the second major lacuna, more unforgiveable than the first: the Umayyad ruler Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (r. 685-705).

The bizarre thing about the film is that it does identify the Umayyads’ war with Ibn al-Zubayr as an inflection point in the development of Islam, and correctly identifies the end of that war as the moment when the qibla changed from the original Sacred House to the Hijazi Mecca,84 but it manages not to mention Abd al-Malik at all. Perhaps this is an instance of bad faith: Gibson’s thesis, relying on fragments from Al-Tabari, that Ibn al-Zubayr moved the ka’ba to Mecca and first reoriented the qibla, falls to pieces under the weight of evidence that Abd al-Malik did both things as part of his broader project to separate the Ishmaelite creed from its Judeo-Christian seedbed.85 Perhaps it was a recognition that to even name Abd al-Malik in passing as the man who defeated Ibn al-Zubayr would raise awkward questions that led to the omission. Or perhaps it was just honest ignorance born of motivated reasoning that led to Gibson miss what should have been in front of his face.

Gibson’s Use of the Sources

In discussing the Qur’anic verses about the qibla change and the unreliability of the later Tradition that imposed a narrative of a move from Jerusalem to Mecca upon it, Gibson seems to get the dynamic described above. But then he invokes the earliest surviving biography of the Prophet, which was completed about 830 AD. Gibson does not mention this late date, and, worse, he names Ibn Ishaq as the author.

The document we actually have is Ibn Hisham’s Al-Sira al-Nabawiyya (The Life of the Prophet), which is formally a recension of Ibn Ishaq’s Sirat Rasul Allah (The Life of the Messenger of God), written seventy years earlier. The difficulty is that the period separating the two documents is exactly when the Tradition was being formulated, which radically recalibrated the nature of the creed and set in place the great contest for religious authority that shaped Islamic history between the caliphs and the ulema (jurists).86 With Islam in its “final form” beginning to emerge into the ninth century, a secular historian would always have had to suspect that Ibn Hisham, writing on the other side of this revolution from Ibn Ishaq, had reworked the prophetic biography to conform with the new understandings of Islamic theology, sacred history, and State power. As it is, there is no need for guesswork. Ibn Hisham states flatly: “Things which it is disgraceful to discuss; matters which would distress certain people; and such reports as al-Bakka’i told me he could not accept as trustworthy—all these things have I omitted”.87

Gibson raises the fact that Al-Bukhari is writing well into the ninth century AD, two-hundred years after Muhammad’s death, in the context of doubting his account that the qibla changed from Jerusalem, only to then quote Al-Bukhari several times later on for details about the Prophet’s city that Gibson believes point to Petra. This is not automatically invalid. For example, the so-called “Constitution of Medina” or “Medina Document” (Sahifat al-Medina), a treaty signed with Jews in Yathrib shortly after Muhammad arrived in the city in 622 AD,88 is only available in Ibn Hisham’s biography and the Kitab al-Amwal (Book of Revenue) by Abu Ubayd al-Qasim ibn Sallam (d. c. 838), literary products of Al-Bukhari’s era.89 Yet the consensus of modern critical scholars is that the Sahifat is genuine because its language is stylistically different from everything surrounding it and its contents are ideologically awkward for the Islamic orthodoxy that was stabilising in this period. So, there are fragments of authentic early material preserved in the Tradition. There is no evidence Al-Bukhari contains such fragments, though.

Al-Tabari is used by Gibson without noting that he was writing in 915 AD. Gibson is surely correct that Al-Tabari’s entry for 70 AH is influenced by later developments, but it is unlikely there was any “editor”: writing in the aftermath of Abd al-Malik’s reforms and the crystallisation of Islamic orthodoxy, what else was Al-Tabari going to write?

By looking at these parts of the Tradition, Gibson neglects the Qur’an, which contains the firmest evidence for his thesis.

Evidence Muhammad’s Ka’ba Was in the Levant

Gibson, it is true, does not wholly ignore the Qur’an, but the uses he makes only restate the problems. When Gibson raises the Qur’an’s lone mention of Mecca, he omits that the reference is to “the valley of Mecca”.90 In other words, the Qur’anic “Mecca” reference is not to a city, and thus is blatantly a separate location to “Becca/Bakka”. It is unclear why Gibson does not highlight this. Potentially the answer is that it undercuts his speculation that “Mecca” in the Qur’an is an interpolation.91 Even less clear is why Gibson, having undersold his own observation about the complete absence of Mecca in pre-Islamic sources,92 then fails to highlight that the first non-Islamic mention of Mecca as a city, in 741 AD, places it in Mesopotamia.93

The Qur’an contains extensive evidence for Gibson’s contention that Muhammad’s umma was in an agricultural setting, yet he mentions none of it. The enemies of the narrator of the Qur’an, the mushrikun, are described as cultivating “crops and cattle”.94 Sowing seeds and growing crops are lifeways for people in the city of the Qur’an community.95 The Qur’an speaks of Muhammad’s followers living in an area where water “poured down … abundantly” and “caused to grow therein grain, and grapes and clover, and olives and date-palms, and gardens dense with foliage, and fruits and herbage, a provision for you and for your cattle”.96 In another place, the God of the Qur’an says his people have been sent “water from the sky” that “brought forth with it the growth of every thing; … grain in clusters; and from the date-palm, … and gardens of grapes, and the olive and the pomegranate”.97 It is reiterated in the Qur’an that the people it is addressing grow olives and pomegranates.98

Animal husbandry and agriculture were not features of life in Mecca, as works that hew closely to the Tradition concede.99 The Meccan climate could theoretically have allowed dates to be grown there, but the lack of irrigation makes even growing that crop in the seventh-century Hijaz doubtful. Pomegranates could have grown at an oasis like Yathrib (Medina).100 The scale of the rainfall, the cattle, and the variety of crops is highly indicative of a Levantine setting, and the clinching detail is the olives: impossible to grow in Arabia, south or north, localised from Late Antiquity up to the present in the Mediterranean Basin, with what is now Israel and Jordan as core areas.101

It would have taken explication, but there is also the issue of al-mushrikun, “the associators”, themselves: when the Tradition-imposed notion that they are literal pagans is removed, what the Qur’an actually discloses is an argument among Biblical monotheists about the status of angels. Muhammad’s opponents are accused of shirk (association), in the sense of ascribing partners to God, because they supposedly believe angels are on the same level of worthiness to be worshipped as God, even that angels are manifestations of God or at least the offspring of God, “implying some sort of identity of essence.” Muhammad’s accusation of polytheism is, therefore, a polemical device, comparable to the way sixteenth-century Protestants accused Roman Catholics of being “pagans” and “idolaters”, with the difference that in Islam this polemic was literalised in the historiography written 150-plus years later by people who had no knowledge of the context.102 Muhammad arguing abstruse points of doctrine with the mushrikun, who otherwise share his whole conceptual universe—the same God, the same expectation of an imminent Last Judgment—is not surprising by the lights of the Qur’an, since it describes both sides of the debate as one people.103 And the debate itself, the rhetorical form and particularly the angelology, is very distinctive to the Biblical communities in and just beyond the frontier of the Roman Levant in Late Antiquity.104

On it goes. The one citation of the Romans in the Qur’an refers to them being defeated in battle “in a nearby land”,105 which is true from the vantage point of the Levant and untrue for those in the Hijaz. The people of Midian, named for a son of Abraham, whom Muhammad has multiple run-ins with in the Qur’an, are quite precisely located by the Classical geographers, east of the Gulf of Aqaba, near the modern-Saudi-Jordanian border.106 Another people Muhammad confronts, the Thamud, were based in Hegra (or Mada’in Salih) in northwest Arabia, 500 miles from Mecca.107 Moses is the most-frequently mentioned figure in the Qur’an by some way,108 the prophetic model Muhammad is overtly adopting,109 and he is famously associated with a Promised Land that is not in Mecca, but is in the same district where all these other clues point.

This does leave the question of why Mecca was ultimately chosen, and we do not know and probably never will. Gibson’s argument that Ibn al-Zubayr moved the ka’ba to Mecca is unconvincing for various reasons, one of them being that his bid for power was based on a “back to basics” premise that, importantly, for the first time invoked the cult of Muhammad, a figure who had been forgotten for nearly half-a-century, partly it seems as a byproduct of the early Tradition conforming Muhammad to the Mosaic role he was acting out,110 telling of him dying before reaching the Promised Land, when he probably had not.111 Ibn al-Zubayr, an old man who had lived contemporaneously with the Prophet and was relying on him for legitimacy, seems unlikely to have given up Muhammad’s city. Abd al-Malik understood the power of the Muhammadan cult and annexed it after the defeat of Ibn al-Zubayr,112 enshrining the doctrine of prophetic authority out of which grew the Hadith and subsequent creedal evolution that resulted in Islam. All of which, admittedly, only replaces the question of why he chose Mecca.

Gibson mentions the existence of a pre-Islamic pan-Arabian ka’ba, and there is evidence that there was such a thing in the north at the time of Justinian (r. 527-565).113 It is possible this became the first Ishmaelite ka’ba and it certainly seems likely that the pre-existing sentiment for an all-Arab ka’ba was adapted by the new monotheism. What Gibson does not stress is that cubes (ka’bas) were common across Arabia as shrine objects, and there was another pre-existing habit, equally likely to hold over to the monotheistic era, of abruptly abandoning one ka’ba and turning to another.114

With Muhammad’s ka’ba physically demolished twice over, Abd al-Malik had a choice to make about where to locate the sacral heart of his Empire, and the knowledge that his subjects were habituated to accepting a move if he decided on one. There was every incentive to have it somewhere else, away from a restive town and at a clear remove from the holy city of the other monotheisms he was beginning to dissociate the Arab creed from. Maybe there was some tradition—whether remembered, recovered, or invented—linking Muhammad with Mecca that was a pull factor. At least as probable is that once a move was decided on, there was not much of a choice about the location. The number of options for a shrine that had the requisite heft by the metrics of pre-existing practice and the new monotheistic paradigm was likely limited, with the selection of Mecca being more default than design.115

So, Was it Petra?

For all the criticism I have made of Gibson, it bears repeating that, according to the best evidence we have, he is correct in the big picture that Islam originates in the area south of Jerusalem. In my judgement, his evidence goes no further than that. The textual evidence he adduces about the ka’ba’s location in Islam’s formative period points squarely to the Levant, and in his focus on the qibla he would have been better heeding his own warning that tracking its direction is “not an exact science”.116 Deficiencies in the presented evidence notwithstanding, he still could be correct. I happen to know that at least one of the great “revisionist” scholars believed al-Masjid al-Haram was in Petra.

If pressed, my own diffident, provisional conclusion is that the original ka’ba was somewhere remoter than Petra and further north, nearer the Dead Sea. The Qur’anic reference to the “distant path” travelled to get to the Sacred House,117 and the uncultivated valley nearby,118 suggests to me an isolated location out in the desert. Petra is too connected, populous, and green to match this description. Another indicator in the Qur’an is in a verse where Muhammad is threatening the mushrikun with annihilation if they do not shape-up. To emphasise the point, Muhammad draws attention to the fate of the towns that were wiped out after the inhospitable treatment of Lot: “Verily, you pass by them in the morning and at night. Will you not use reason?”119

Since the days of Josephus, in the first century AD, Jews and Christians had located Sodom and Gomorrah as being on the southern shore of the Dead Sea, which was itself often known as “the Lake of Sodom”.120 This conviction was entrenched, and marked in the very landscape, by the early seventh century. The Bible tells of Lot and his daughters taking shelter in Zoar, another of the “cities of the plain”, as God’s wrath is visited on Sodom and Gomorrah, but finding it too close for comfort and retreating to a cave.121 Zoar was identified in the fifth century as a town on the southeastern bank of the Dead Sea, modern Gawr as-Safi, and at Lot’s Cave, identified in a nearby mountain, a church and monastic complex had been erected.122 The widespread recognition and veneration of the Church of Saint Lot is evident in records from the sixth century.123 Muhammad arguing in the 610s-20s with people he describes as “pass[ing] by [the ruins of Sodom and Gomorrah] in the morning and at night”, therefore, places him in a quite specific location within the Roman Palaestina border zone.

Post has been updated to add some details about the Arab foederati

FOOTNOTES

One example given by Gibson from the Hadith: “The Prophet said, ‘Allah has made Mecca a sanctuary [or sacred place] and it was a sanctuary before me and will be so after me. … None is allowed to uproot its thorny shrubs or to cut its trees or to chase its game” [Al-Bukhari 23:432].

Gibson has a longer discussion of the structure of Arab paganism, saying that, as with its Greek and Roman counterparts, it meant Arab tribes and peoples had no issue with the idea that there were different gods in different places, and if they passed through those places they made obeisances to the local deities to avoid their wrath. A difference the Arabs had with Greco-Roman pantheons was an aversion to human or animal representations of the gods, according to Gibson. The Arabs tended to represent gods as geometric shapes like triangles or blocks. The upshot is that the Arabs took for granted that certain territories were sacred to certain gods, and more specifically that the central temple or shrine of these gods was more sacred still, with the precinct areas around the shrines where votaries gathered marked out as sanctuaries in which killing was forbidden.

Of Gibson’s eleven early mosques, the ten Middle Eastern ones are in: Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, Israel and the broader former Mandate Palestine, Lebanon, and Yemen.

On the dating of the Lighthouse Mosque in Guangzhou, Gibson is totally credulous, recycling the Tradition that it was built by Sa’d ibn Abi Waqqas, a Companion, uncle, and cousin of the Prophet’s who supposedly became the military leader of the Arab Empire after Muhammad’s death and is most celebrated in Islamic historiography for playing a leading role in the conquest of Iran. The mosque was almost certainly built later, perhaps as much as a century later.

Gibson does not go into this in too much depth for understandable reasons of space, but it is striking how much of a role Humayma plays in the Islamic story of the Abbasid rise to power. The lead organiser of the Abbasid Revolution, Ibrahim al-Imam, was a Humayma native and coordinated from that town the actions out in the east, in Khorasan, which ultimately swept the Umayyads from power. Ibrahim died just before the Abbasids prevailed, but his father, Muhammad al-Ibrahim—the great-grandson of Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib, an uncle of the Prophet’s, the namesake of the dynasty and the hinge of their claim to legitimacy—had two other sons who served as the first two Abbasid Caliphs, Al-Saffah (r. 750-54) and Al-Mansur (r. 754-75); both had been born in Humayma. The third Abbasid Caliph, Al-Mahdi (r. 775-85), Al-Mansur’s son, was also born in Humayma, reportedly in 744.

Gibson could have added that the Quraysh are difficult to locate at all outside the Islamic Tradition, but as we shall see this omission is of a piece with the rest of the film.

Gibson does not include this, but the biography is quite specific that “when they came to Mecca they saw a town blessed with water and trees”. See: The Life of Muhammad: A Translation of Ishaq’s Sirat Rasul Allah, trans. A. Guillaume (1955), p. 46.

See: Guillaume’s The Life of Muhammad, p. 176.

Ibn al-Zubayr, a man in his late 50s with a stellar reputation as one of the military leaders during the Arab conquests, and a grandson of the apparent first Rashidun Caliph, Abu Bakr, did indeed declare himself Caliph in 683, precipitating the major phase of the Umayyads’ war with him. There are a number of errors in Gibson’s chronology and details, though.

The Second Fitna, according to the Islamic historiography Gibson relies on, began a few years earlier with the appointment of Yazid I as the Umayyad Caliph in April 680. Ibn al-Zubayr refused to give bay’a (oath of allegiance) to Yazid, as did the Shi’i Imam, Husayn, the grandson of the Prophet and son of Ali, the fourth Rashidun Caliph. Ibn al-Zubayr and Husayn are said to have met in Medina, Ibn al-Zubayr’s hometown, and Husayn was invited to Kufa, where people sympathised with him. Husayn was ambushed on the way, cut down at Karbala on 10 October 680, an event commemorated every year by Shi’is with the Ashura mourning festival.

Ibn al-Zubayr evaded arrest in Medina and slipped away to the ka’ba city, where he set himself up as a rival. Seeing this, not unreasonably, as rebellion, in August 683 (again, all dates from the Tradition) Yazid dispatched troops to deal with Ibn al-Zubayr, whose forces retreated to al-Masjid al-Haram. The ka’ba was destroyed and technically perhaps Ibn al-Zubayr was responsible, but this seems misleading from Gibson. The ka’ba is reported to have been badly damaged in the fighting—some sources say by catapults, some in a fire—and Ibn al-Zubayr then demolished the remnants.

Yazid suddenly died in November 683 and the Umayyad army around the sanctuary melted away when brought the news, returning to Damascus to give bay’a to Yazid’s teenage son, Muawiya II, and jockey for position at the new Court. What Gibson gets out of sync is that it is at this point that Ibn al-Zubayr proclaimed himself the rightful Caliph—to succeed Yazid, not against him. Gibson’s claim that Muawiya II died after just forty days on the throne is unproblematic; the sourcing is very unclear on the exact length of the reign, but it was not longer than two months.

Fred Donner, ‘The Qur’an in Recent Scholarship: Challenges and Desiderata’, in Gabriel Said Reynolds [ed.] (2007), The Qur’an in Its Historical Context, p. 43.

Admittedly, all I know about Gibson is from this film and skimming some of his writings, but if he has an agenda one would expect to see it reasonably quickly. It might also be noted—as this article gets into—that Gibson’s errors result in him missing some of the best evidence for his own case. In other words, the errors are not all in one direction. It could be that he is an activist and incompetent—the combination is not unknown—but Occam’s razor suggests his mistakes are honest.

In Islam, “innovation” (bid’a) came to have roughly the same connotation as “heresy” in Christianity. See: Bernard Lewis (1982), The Muslim Discovery of Europe, p. 224.

Bernard Lewis (1995), The Middle East: A Brief History of the Last 2,000 Years, p. 51.

The physical danger that everyone understands as an impediment to critical examination of Islam in any form is a phenomenon of the last few decades. It cannot explain why the source-critical scholarship on Islam, which began in the mid-nineteenth century, remained so broadly reliant on the Islamic Tradition for a century and more. The issue was the sheer difficulty for non-Muslim scholars of constructing an explanation for Islam’s origins that does not rely on the Tradition. The evidence for Islam’s formative period outside the Tradition is so agonisingly thin that many scholars went only so far as reworking or reinterpreting material in the Tradition.

What made the 1970s a rupture point was the emergence for the first time of a significant cadre of scholars who argued for disregarding (at least most of) the Tradition. This produced broadly three forms of revisionism. First, those who worked on discrete aspects of philology, history, or archaeology without the assumptions of the Tradition, but made no attempt integrate their findings into the wider story. Second, those, exemplified by Wansbrough, who effectively argued that historical reconstruction was impossible and examined the Tradition as a literary canon. Third, those who attempted to piece together an alternative narrative of the origins of Islam. The results from this third category radically differ among themselves and many fell into a kind of epistemological no-man’s land, where their assemblage of the threadbare evidence is plausible, but not strong enough to gain a scholarly consensus nor obviously wrong enough to be definitively refuted.

By the twenty-first century, however, the revisionists had reshaped Islamic Studies as a field. The revisionists have not triumphed—their internal heterogeneity makes it difficult to imagine what that would even look like—but the Tradition-oriented pre-1970s consensus has been decisively broken. The outcome has been disarray to some extent—what some even call a “schism”—though methodologically there are signs of agreement coalescing around the study of the Late Antique context in which Islam emerged.

Gerald Hawting (1997), ‘John Wansbrough, Islam, and Monotheism’, Method and Theory in the Study of Religion. Available here.

There is a long-running debate about whether the Qur’an contains traces of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The textual evidence, notably in the Qur’an’s discussion of “the people of trench” (85:4-10), suggests so. The difficulty has always been more about the logistics. The oldest parts of the Dead Sea Scrolls were written in the late third century BC and the newest parts date to the late 60s AD, leading to the conclusion they were buried in the Qumran Caves, on the northern shores of the Dead Sea, early on in the Judean rebellion. The Scrolls were recovered in the 1940s-50s.

While the Tradition’s account of Muhammad being born and raised in the Hijazi Mecca makes it most improbable he would have discovered the Scrolls in the Judean Desert, that is what the Tradition is designed to do—to eliminate temporal explanations for Muhammad having access to Biblical monotheism. Even if Gibson were right that the Sacred House was in Petra, that is still 150 miles away; the possibility of an accidental discovery seems minimal. If the ka’ba was further north, nearer the Dead Sea, an accidental discovery might still be improbable, but perhaps there is some chance of the Qur’an author being directed to the Scrolls, on the heroic assumption any locals knew of the Scrolls half-a-millennium and more after their burial, and Muhammad or one his followers encountered such a person.

Of course, the logical problem here is that the Scrolls were discovered in the Qumran Caves. To get around this, the explanation would have to be that Muhammad put them back, despite no evidence of prior disturbance, or Muhammad found them at another location and it was he who put them in the Qumran Caves, or he never had contact with these specific Scrolls but found copies or fragments of copies somewhere else. The old standby of Muhammad picking up oral traditions on his travels might square this circle, if someone can come up with a theory—and ideally some evidence—for a nearby Jewish community holding to the apocalyptic, Qumranic ideas that, so far as we know, were obliterated centuries earlier. The complete lack of evidence means we are reduced to theories that rapidly accumulate so many layers of conjecture they seem more like the contents of a Dan Brown novel than the outcome of historical inquiry.

The Apocalypse of Abraham, a Jewish apocalyptic text probably dating from the early second century AD, mostly consists of a dialogue between Abraham and the Angel Yahoel, and its eschatological theology unfolds in a series of eschatological visions. The text is highly polemical and some of its main concerns are angelology and anti-idolatry. It is impossible not to notice a resemblance in format and themes between the Apocalypse of Abraham and the Qur’an, and some scholars argue that elements of the Qur’an text are drawn directly from the Apocalypse of Abraham, for instance in Sura al-Tawba (chapter nine). See: Gabriel Said Reynolds (2010), The Qur’an and Its Biblical Subtext, pp. 78-79.

The Qur’an story (4:157) that Jesus was not crucified derives from the Gospel of Basilides, a gnostic tract condemned as heretical by the Church Fathers as far back as the second century AD. The Qur’an (19:23) tells of Mary giving birth to Jesus under a tree, which is not only the kind of detail that was included in the Infancy Gospels, it is a detail from the Gospel of James, also from the second century, a widely-read text well into the early medieval period that significantly shaped popular Christian beliefs about the life of Mary. (The Protoevangelium of James was condemned and faded, but its contents were transmitted through The Book About the Origin of the Blessed Mary and the Childhood of the Saviour—or the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew—produced under the Carolingians, perpetuating a lot of the details and narratives into the popular Christianity of the High Medieval Latin West.)

For a good overview of this point, see Angelika Neuwirth’s lecture to the Institute for Advanced Study, ‘The “Late Antique Qur’an”’ (2012). Available here.

For the full argument, see: John Wansbrough (1978), The Sectarian Milieu: Content and Composition of Islamic Salvation History.

Indeed, a “considerable” part of the Qur’an is “the transcript of debates” in the Late Antique sectarian milieu. This has implications for the authorship, too: whoever physically generated what became the Qur’an text, part of what is going on in the text is the development of a creed as the Prophet interacts with an audience, sharpening arguments against opponents, while deepening his theology among a growing number of followers whose composition is changing. In that sense, the Qur’an is a sort of meta-transcript of the dual processes of evolution in the Prophet’s ideas and those ideas becoming a communal identity. See: Angelika Neuwirth, ‘The Qur’an’s Enchantment of the World: “Antique” Narratives Refashioned in Arab Late Antiquity’, in, Majid Daneshgar and Walid A. Saleh [eds.] (2016), Islamic Studies Today: Essays in Honor of Andrew Rippin, pp. 130-31.

Hawting, ‘John Wansbrough, Islam, and Monotheism’.

The fascinating exception is Himyar (Yemen), where a Jewish dynasty was established in 390 AD. The obliteration of paganism in the realm seems to have been thorough thereafter [Eric Maroney (2009), The Other Zions: The Lost Histories of Jewish Nations, pp. 92-93]. Reports of a terrible massacre of Christians at Najran in 523 led the outraged Christians of Ethiopia and Byzantium to intervene and install a Christian vassal in Himyar. This alarmed the Sasanid Persians, who formally annexed Himyar in 570, though ruled it more indirectly and did not insist on enforcing Zoroastrianism [Peter Sarris (2011), Empires of Faith: The Fall of Rome to the Rise of Islam, 500-700, pp. 139-45]. Thus, the centre of Arabia, with its nomadic tribes, was of little interest to the Romans and Persians, and remained in some isolation, though exactly how completely, we do not know [Holger Zellentin, ‘The Rise of Monotheism in Arabia’, in, Josef Lössl and Nicholas J. Baker-Brian [eds.] (2018), A Companion to Religion in Late Antiquity, pp. 157-80]. But the southwest and Red Sea littoral was a theatre of the Late Antique superpowers’ Great Game for two hundred and more years before Muhammad appeared, with all that entailed of cultural-religious influence on the Arabs therein.

Irfan Shahid (1984), Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fourth Century, pp. 115-17.

Foederati were formally allies of the Roman people, Barbarian tribes bound by treaty to Rome. The practice was an ancient one, dating back to at least the first century BC in the west, and there was little novel about its format when it was expanded to the east, albeit the Romans had previously seen the Arabs as too inveterately fractious to be of any use. The Arab foederati were enrolled in a “partnership”, a shirkat, which in the long-run would lead to Arabs being known as “Saracens”. See: Michael C.A. Macdonald (1995), ‘On Saracens, the Rawwafah Inscription, and the Roman Army’, in, M.C.A. Macdonald (2009), Literacy and Identity in Pre-Islamic Arabia. Available here.

Ilkka Lindstedt (2024), ‘A Map and List of the Monotheist Inscriptions of Arabia, 400-600 CE’. Available here. In terms of the vector for monotheism into northern Arabia, many settled Christian Arabs had relatives beyond the Roman borders, who lived semi-nomadically most of the year, but settled within the limits of the Empire or in its Arab client Kingdom during the winter, before heading back out in the spring. See: Greg Fisher, ‘Introduction’, in, Greg Fisher [ed.] (2011), Between Empires: Arabs, Romans, and Sasanians in Late Antiquity.

Peter J. Heather, ‘Foedera and Foederati of the Fourth Century’, in Thomas F.X. Noble (2006), From Roman Provinces to Medieval Kingdoms, pp. 108-33. Available here.

Richard Bell (1925), The Origin of Islam in its Christian Environment: The Gunning Lectures, pp. 18-28.

Mariana Castro (2018), The Function of the Roman Army in Southern Arabia Petraea, p. 76.

Tom Holland (2012), In the Shadow of the Sword: The Battle for Global Empire and the End of the Ancient World, pp. 283-85.

In the Shadow of the Sword, pp. 324-25.

Even in the more Tradition-reliant account, it is remarked upon how stunningly suddenly and totally the Ghassanid Arabs went from being “the bulwark of the Roman Empire and of Christianity” to being soldiers of Islam. See: The Origin of Islam in its Christian Environment, p. 182.

Stepping outside the assumptions of the Tradition, the answer might easily be that there was no “conversion”: the Ghassanids—or leading elements from the fallen Kingdom—may have seen the attraction of a creed that required of them little doctrinal compromise and entitled Arabs to the rule, and resources, of Palaestina, without the oversight of Constantinople and its condescending bishops who kept hectoring them about their “erroneous” understanding of the nature of Christ. In turn, if the Ishmaelites had footholds around southern Roman Syria and some substantial Ghassanid support within when they made their move on their Holy Land, what the Tradition casts as a grand invasion from faraway Medina might well have been more of an internal collapse, the implosion of a Roman authority that had only recently been restored after the Persian occupation and was only being upheld by Arab foederati whose payments had become irregular. If this is so, it would explain the archaeology, which finds that the “conquest did not create extensive destruction or long-lasting disruption”. See: Robert Schick (1998), ‘Archaeological Sources for the History of Palestine: Palestine in the Early Islamic Period’, Near Eastern Archaeology. Available here.

Gerald Hawting (1999), The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam: From Polemic to History, pp. 38-39.

The narrative of an Apostle formulating his Biblical creed in the Arabian desert, isolated from the urban fleshpots and free from all earthly inputs, even from other monotheists, communing with God alone, is not unique to Muhammad. The story emerges with Saint Paul, who went into the Arabian wilderness soon after his “conversion” to mediate and crystalise his teachings. All his life, Paul insisted he received his revelation from Christ directly and drew nothing from any other Christian. See: Galatians 1:11-19, and, The Origin of Islam in its Christian Environment, pp. 15-16.

The Sectarian Milieu, pp. 126-29.

In the Shadow of the Sword, p. 50.

Peter Brown (1971), ‘The Rise and Function of the Holy Man in Late Antiquity’, The Journal of Roman Studies. Available here.

Qur’an 3:7. The word used is “mutashabihat”.

This genre begins with the Kitab al-Tarikh wa al-Maghazi (Book of History and Campaigns), often called simply Kitab al-Maghazi, completed by Al-Waqidi (d. 822) shortly before his death, perhaps to coincide with the bicentenary of the Islamic calendar (815-816 AD).

Moses Finley (1965), Myth, Memory, and History, p. 295.

There are some fragmentary traces of the Islamic Tradition remaining to us from the second half of the eighth, but nothing substantial. Even texts attributed to the late eighth century typically exist only in ninth-century versions. A classic example is Ibn Ishaq’s Sira (c. 760 AD), which nominally survives in Ibn Hisham’s recension, dated by Tradition itself to around 830. Moreover, Muslim Tradition has a habit of attributing important theological texts that were formed over considerable periods of time to great figures of the past, which has led some scholars to suspect that works conventionally thought to be authored by figures in the early ninth century were actually stabilised into their extant forms later. See: Norman Calder (1993), Studies in Early Muslim Jurisprudence.

The Sectarian Milieu, p. 49.

The Persianate influence on Islam in general is extensive and obvious. Many hallmarks of Islam’s “golden age”, from the “Round City” of Baghdad to the “House of Wisdom” library, are modelled on Persian predecessors. (The city was even designed under the direction of a Persian astrologer, Al-Naubakht—and a Jewish astrologer, Mashallah.) Once the Tradition stabilised, Muslims had come to believe apostates should be executed, prayers should be said five times a day, and cleaning their teeth with a miswak was pleasing to God. The Qur’an says hell is the punishment for apostasy (2:217; 3:86-88; 16:106-109) and prescribes three prayers per day (24:58), while keeping silent about dental hygiene. Sidestepping the question of how Sunna could be formed in defiance of the Qur’an if the Book was the source of communal identity, it is no mystery where these ideas came from: all were features of Zoroastrian creed and custom.

The parallel between Rabbinic Judaism and Islam in resting on the twin pillars of revealed scripture (Tanakh, Qur’an) and an interpretive tradition (Oral Torah, Sunna) is striking. Perhaps it is a coincidence that the earliest and most influential school of Islamic law was formed in Kufa, thirty miles north of Sufa, home to one of the two greatest yeshivas in existence. Perhaps it was incidental that so many ex-rabbis became ulema, tracing isnads and producing shari’a codes. Islam setting aside the Qur’anic advice (24:2) to lash adulterers in favour of the capital sentence recommended by the Tanakh (Deuteronomy 22:21): perhaps also contingency. A more parsimonious reading of the evidence is that Jewish converts brought their legal-doctrinal assumptions with them and embedded them in the fabric of emergent Islam.

See: In the Shadow of the Sword, pp. 405-10.

Muslim creed (aqeeda) holds that, while the Qur’an was verbally revealed to Muhammad verbally by the Angel Gabriel (Jibril) over twenty-three years (610-32 AD), the Qur’an itself is “uncreated” (ghayr makhluq), having existing eternally as the “speech of God” (kalam Allah), one of His attributes. There was a challenge to this view by the Mu’tazilites in the early ninth century in Abbasid Iraq, and for a time Mu’tazilism was supported by the Caliphs. The Mu’tazilites losing official patronage in 847 AD was part of a larger story of the Caliphs losing their sacral role to the ulema, a process that—inevitably, in an Empire where “religious” and “political” authority were fused—leeched the Caliphs of temporal power.

This narrative about the method of the revelations is used to explain a feature of the Qur’an that strikes any reader: its disjointedness. The Qur’an is sometimes called “the Muslim Bible”, but this is a category error.

The Tanakh and the New Testament are narrative texts that contain the names of contemporary figures, indicating the dates; stories take place in or near identified cities and geographic landmarks, giving the place; episodes in the surrounding world are mentioned (e.g., the Roman census in the Gospel of Luke); the social landscape is documented (e.g., the presence of groups like priests, soldiers, even tax collectors, and the cultural practices specific to them); and journeys are described in concrete and chronological terms. In short, Jewish and Christian scripture is grounded in time and space, which allows historians to triangulate with external evidence to assess the reliability of claims about the socio-political environment, i.e., whether the material authentically originates where and when it claims, or is a later back-projection.

The Qur’an is a record of prophetic speech, most of it in the context of sectarian polemic. Even where the Qur’an gives “stories”, the narrative is “episodic”, as Wansbrough puts it (The Sectarian Milieu, p. 14). For an example, see the Qur’anic description of the confrontation with Pharoah and his magicians (7:103-126, 20:56-73, and 26:34-51). The emphasis is on speech: the Qur’an narrates what was said by Pharoah and God’s representative to the didactic end of showing the triumph of God’s will and doctrine. That overlapping renditions of the episode recur throughout the Qur’an makes the point in another way: the polemical theology is the point. There is little internal sense from the Qur’an of when or where events happen, nor how they come about, i.e., the causes of events and even their chronology is opaque. Biblical episodes from before Muhammad appear only to reinforce his creedal message, and any details that appear about the Qur’anic Prophet’s ministry—narrated by Muhammad or God—appear incidentally as the Qur’an text sets out his arguments against opponents. It is these incidental shreds—and the fragmentary non-Ishmaelite sources from the first decades—that historians must work with to try to reconstruct what happened and why to turn the Roman-Persian Near East into an Arab one.

Some of the most celebrated parts of Muslim orthodoxy come from the Tradition imposing meanings on Qur’anic verses that are far from self-evident. The idea of Muhammad being illiterate, for example, comes from two Qur’anic verses: 7:157 and 29:48. The former refers to “the ummi Prophet”, often translated as “unlettered”, but it can also mean “lacking a scripture” in the sense of not being Jewish or Christian, and in the context of the rest of the aya this would seem to make more sense. Elsewhere in the Qur’an (25:4-6), it is strongly implied Muhammad can read and write, and Ibn Hisham’s biography suggests the same thing. See: In the Shadow of the Sword, p. 528 (footnote).

John Wansbrough (1977), Quranic Studies: Sources and Methods of Scriptural Interpretation, p. 69.

Fred Donner (2010), Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam, p. 51.

The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam, pp. 32-35, 39-43, 51-55.

Donner, ‘The Qur’an in Recent Scholarship’, in, The Qur’an in its Historical Context, p. 29.

Islamic historiography says the Qur’an circulated orally in the Prophet’s lifetime, was written down soon afterwards, and existed briefly in seven ahruf (forms) until Uthman chose one and burned the rest. The Uthmanic recension was not, however, even according to the Tradition, the complete end of Qur’anic variance, but the differences were said to be insignificant after the tenth century, when Ibn Mujahid delineated seven canonical qiraʼat (readings) of the Qur’an (later expanded to ten), and there is no reason to disbelieve this aspect. The differences in the post-tenth century versions of the Qur’an do seem to be genuinely minor: vocalisation, grammar, and the occasional word. The 1924 Cairo Edition has become something akin to a “standard” Qur’an, but variance has not been totally suppressed.

Quranic Studies, pp. 45-50.

John of Damascus, an Arab Christian born in Damascus c. 675 AD under the Umayyads, was a senior civil servant in the latter years of Abd al-Malik’s reign and became a monk c. 730, before dying in 749. John took a great interest in the creed of those he called “Ishmaelites” and around 735 he wrote a detailed polemical refutation in Concerning Heresies. John refers to Arab “scriptures” (plural), and calls them “The Women” (Al-Nisa), “The Table” (Al-Ma’idah), and “The Heifer” (Al-Baqarah), which are all suras (chapters) of the Qur’an, and to “The She-Camel”, which is not a sura, though some of the contents John describes appear in scattered allusions in the Qur’an. Having written more extensively about the Ishmaelite “heresy” than any of the others, John’s tract still leaves us more questions. It seems so unlikely that somebody who had been so close to the Caliphal Court could be unaware of the Qur’an. And yet the implication of John’s writing is stark: Muslims were following a collection of separate books that had not yet been canonised into the Qur’an very late in the Umayyad period. See: Daniel Janosik (2016), John of Damascus, First Apologist to the Muslims: The Trinity and Christian Apologetics in the Early Islamic Period, pp. 106-10.

Another Christian writer, nearly half-a-century on, Timothy I, the Patriarch of the Church of the East, engaged in a debate with the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mahdi (r. 775-85), and in that discussion Timothy does explicitly name the Qur’an and speaks of features, such as the “disjointed letters” (al-huruf al-muqatta’at) at the beginning of some chapters, that are recognisable at the present day. See: Alphonse Mingana (1928), The Apology of Timothy the Patriarch before the Caliph Mahdi, pp. 36, 67-68. At the same time, there are quirks. Timothy quotes a Qur’anic verse he identifies it as being in Sura Isa, i.e., Jesus (p. 41). The verse (19:33) is in Sura Maryam now.

Quranic Studies, p. 44.

Islamic law settled on the death penalty for adultery, but the Qur’an (24:2) is unambiguous that adulterers, male and female, should be lashed one-hundred times.

In a very early source from outside the Islamic literary Tradition, in the 640s, an emir seems to speak of the Torah as the Ishmaelites’ Holy Book. Under Muawiya (r. 661-80) there is not sight nor light of a Qur’an. Muawiya considered himself “Commander of the Believers”, but what he meant by “Believers” is distinctly opaque. Even in the time of Abd al-Malik (r. 685-705), when the first contours of something recognisably on its way to Islam appear, the nearest we get are inscriptions on the Dome of the Rock that contain the earliest text paralleling Qur’anic verses, but the inscriptions raise nearly as many questions as they answer. See: In the Shadow of the Sword, pp. 367-70, 389-90.

The Dome of the Rock inscriptions do not exactly match the Qur’an text, and there is no citation of the Qur’an in the inscriptions. It leaves open the possibility that these pericopes were in circulation as divine revelation, but had not yet been canonised in the Qur’an. The inscriptions themselves—stressing strict monotheism and Muhammad’s role as Messenger on the exterior, polemically anti-Trinitarian on the interior—are missing the Qur’anic verse (17:1) that would be interpreted as demonstrating Muhammad had ascended into heaven from Jerusalem. Perhaps the exegesis had not happened yet. The foregoing assumes the inscriptions date to the time of Abd al-Malik, which cannot be taken for granted. It is uncontested even in Islam’s sacred history that the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mamun edited the inscriptions c. 836 AD. The Tradition insists all that Al-Mamun did was to chisel off Abd al-Malik’s name and add his own, and it is most unlikely there were wholesale changes at this point in the ninth century, but we cannot know this is all he did, introducing further uncertainty. See: Christel Kessler (1970), ‘Abd Al-Malik’s Inscription in the Dome of the Rock: A Reconsideration’, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Available here.