The Soviet Campaign Against Pinochet’s Chile

Yesterday’s post was a review of some of the sources relating to the Sovietization of Chile under Salvador Allende after 1970 and the termination of that process in 1973 by General Augusto Pinochet’s military coup. Today’s post will focus on one particular source about the aftermath.

In 2018, Kim Christiaens published, “European Reconfigurations of Transnational Activism: Solidarity and Human Rights Campaigns on Behalf of Chile during the 1970s and 1980s”. Christiaens is an historian of contemporary and Cold War social movements and “international solidarity” activism, but he is also very clearly one of those activists, with the attendant radical politics, specifically a deep anti-Americanism and overt sympathy for Communism. All of which is to say, the insights from his paper about the extensive Soviet agitprop campaign using the screen of “human rights” in Chile after the 1973 coup come from an evidence-against-interest perspective that bolsters their reliability.

For instance, Christiaens writes:

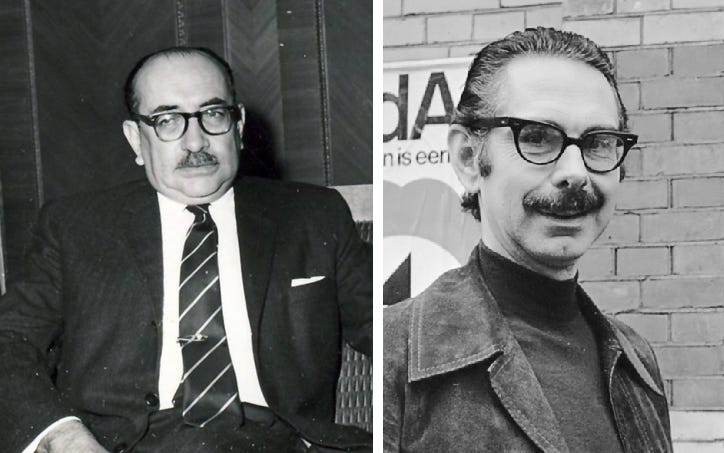

Communist Parties developed into a major organizational axis of campaigns against Pinochet. In many Western European countries, national Chile committees established by Communist Parties and peace movements connected to stage massive demonstrations and humanitarian campaigns. The large Communist Parties in Italy and France turned Rome and Paris into international centres of Chilean exile.

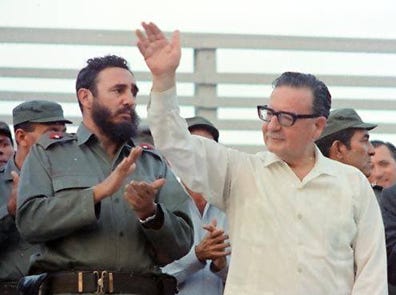

Communist Parties in the West and Communist regimes in the East had been able to profile themselves as allies of the Chilean Popular Unity [the “popular front” coalition Allende ruled through] ever since 1970. Visits of leading Popular Unity members to Eastern Europe and reciprocal visits cultivated the idea of close economic, political, and diplomatic cooperation between the Chilean Popular Unity and Communist Europe … The 1973 coup … allowed the Soviet Union and its allies to profile themselves as the main advocates of the Chilean victims.

Eastern European embassies and diplomats allowed leading figures of the Chilean Popular Unity to flee the country and welcomed hundreds of exiles in Eastern Europe. East Berlin and Moscow quickly became host to the international headquarters of newly created political structures of the Socialist and Communist Party [i.e., Allende’s PS and the Soviets’ PCC] in exile.

Christiaens takes for granted that these Communist campaigns were good things—and not only for raising issues of “human rights” and “peace”. Christiaens writes the above in the context of arguing that Communist agitation over Chile “allowed for East-West cooperation, and bridged rather than widened the distance between Western and Eastern Europe”.

One can sift Christiaens’s framing and analysis out, and retain the important point that much of the anti-Pinochet activism in Europe was organised by the Soviet-controlled Communist Parties, the Soviet colonies in the East, and the Allende government officials and supporters who had put themselves in the hands of the Soviets after they were driven into exile in 1973, either within the Soviet Empire itself or in settlements overseen by Soviet agents in the West.

On this point, Christiaens documents:

Already in the first few weeks after September 1973, human rights violations in Chile appeared on the agenda of a broad assortment of international organizations that were supported by the Soviet Union and socialist countries, including the World Federation of Trade Unions, the World Federation of Democratic Youth, and the International Union of Students.

As early as 22 September 1973, the World Federation of Democratic Youth and the International Union of Students staged a European Youth and Student Meeting in Paris. Gathering Communist youth groups hailing from fifteen Western European and seven Communist countries, this conference developed information campaigns, organized public campaigns such as demonstrations and petitions, collected money to aid the Chilean resistance, and called for the establishment of solidarity committees.

One of the principal fora became the World Peace Council. This Helsinki-headquartered international coordinating body of Communist-led peace movements was established in the late 1940s, developed a series of international campaigns against the Vietnam War and anti-colonialism over the 1960s, and transitioned in the late 1960s into a forum for campaigns on European security and cooperation. In the early 1970s, it successfully campaigned and was recognized at the level of U.N. [United Nations] institutions, for instance on the issue of anti-apartheid.

In late September 1973, the World Peace Council and affiliated Communist peace movements organized in Helsinki what was to be the first major international conference of solidarity with the Chilean resistance. The event was attended by leading figures of the Popular Unity in exile, delegations of Communist parties and governments, national liberation movements (including the South African ANC [African National Congress]), as well as by representatives of human rights NGOs (including Amnesty International and Christian NGOs) from all over Western Europe.

On the one hand, it is scandalous for a scholarly presentation to omit what we know from the Mitrokhin Archive of the World Peace Council (WPC) being a KGB front organisation, entirely financed and controlled from Moscow as a deception operation to blame the nuclear confrontation on Western warmongering.1 But, again, there is value in the tribute vice pays to virtue here. It is very helpful to have from someone so sympathetic such an open and detailed itemisation of the full range of active measures the Soviet Union undertook in the immediate aftermath of the Allende government’s overthrow, and how successful Moscow was in drawing in all the usual Western useful idiots and fellow-travellers, particularly the pacifist religious groups and “human rights” NGOs.

Christiaens (unintentionally) explains how the Soviets used the Chile issue to tighten the reins on some of its Communist Parties in the West that were showing dangerous signs of the “Eurocommunist” heresy in the wake of the crushing of Czechoslovakia in 1968, and to gain access to a wider pool of potential recruits in the radical Left milieu in Western Europe:

During the World Congress of Peace Forces staged in Moscow in October 1973, hundreds of representatives involved in campaigns on behalf of European security and cooperation since the late 1960s turned solidarity with Chile into a symbol that showcased the necessity of East-West détente to combat fascism. The conference was at the roots of an International Commission of Inquiry into the Crimes of the Military Junta, which, in cooperation with leading members of the deposed Chilean Popular Unity, staged a series of international campaigns against Pinochet over the 1970s and early 1980s. Similarly, in Paris in July 1974, delegations from “Socialist Europe”—on both sides of the Iron Curtain—staged a “Pan-European Conference of Solidarity with Chile” under the leadership of the French Communists and socialists.

Among the most interesting things Christiaens confirms is that the output of Western “human rights” groups about Pinochet’s Chile was contaminated with Soviet disinformation from the beginning. “[E]ven … established organizations such as Amnesty International … lacked partners on the ground, avenues for organizing solidarity, and information”, writes Christiaens. The Soviet front-groups—the WPC, the International Union of Students, and the World Federation of Trade Unions—stepped into this vacuum, Christiaens writes, taking the NGOs on guided tours that created “contacts between Chilean exiles [i.e., the Allendists] and Western European NGOs and social movements”. This process not-incidentally “buttressed the legitimacy and appeal of Communist-led campaigns”. Allende’s widow, Hortensia, was an important part of this.

Throughout Pinochet’s rule, Christiaens goes on:

Chilean exile organizations operating in Eastern Europe became key sources of information about the situation inside Chile—even for local groupings in the West.

Later Christiaens notes:

Even in the 1980s, the programme Escucha Chile broadcast by Radio Moscow remained a key source of information for many local committees in Western European countries.

In other words, Western NGOs—and the Western media that relied upon them—were either being fed Soviet propaganda directly, from exiled Allende officials behind the Iron Curtain, or analysts and journalists were speaking to émigrés in the West who were informed by these same exiles.

The Soviet hand behind this propaganda offensive was not hidden:

Many of these initiatives [to connect Westerners, especially the NGOs, with “Chilean exiles”] were supported by Eastern European regimes, and most notably by East Germany.

A particularly successful instance was the campaign to free Luis Corvalán, the leader of the KGB-controlled PCC, who had been imprisoned after the coup, and around whom Moscow “active measures … sought to establish a secondary cult” after Allende’s death.2 The WPC was assigned to lead the effort to spring Corvalán, and according to Christiaens it “resonated all over Western and Eastern Europe, among Christian Democrats, human rights NGOs, and Social Democrats.”

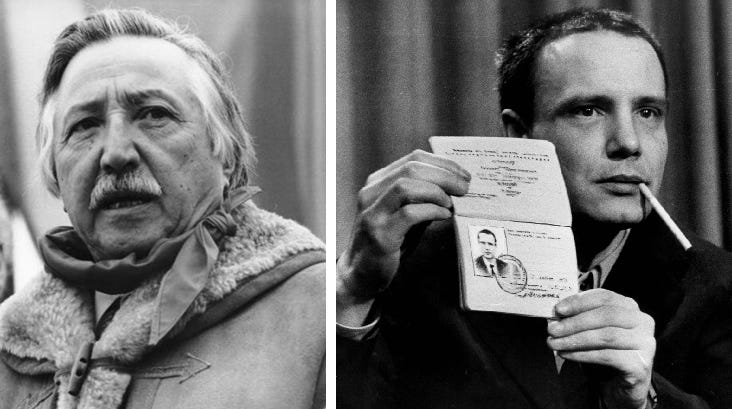

That being said, as Christiaens goes on to document, the release of Corvalán in 1976 proved to be something of a double-edged sword for the Soviets. The price Pinochet demanded was the release of Vladimir Bukovsky, a Dissident whose peaceful campaign calling for the Soviet government to obey its own written laws on free expression and other rights had seen him confined for twelve years to the labour concentration camps and psychiatric hospitals. It elevated Pinochet’s anti-Communist credentials quite considerably.

The WPC led the “Boat for Chile” stunt in 1975, supposedly to take “humanitarian aid” to Chile, something that Chile by then—out from under Allende’s economic mismanagement—did not, in fact, need. But it was a tried and tested formula, modelled on a similar Soviet operation over Vietnam years earlier, and it was successful as a mobilising and unifying tool for the Communist trades unions. The WPC’s foothold at the U.N. was obviously useful in ensuring Soviet propaganda reached a broader audience. One particular aspect of this was embedding the idea in public consciousness that Pinochet’s government was “fascist”—the term the Soviets used for all of their foes, but with a special emphasis over Chile.

Christiaens notes:

Campaigns represented Pinochet and his uniformed soldiers as SS officers, and when the new Chilean ambassador to France arrived in Paris, activists hoisted the Nazi flag. Chilean exiles contributed to this connection: iconic figures of the Chilean opposition, such as Allende’s widow and daughter, visited World War II memorials in the West and East, and when Chile Democrático [“Democratic Chile”, founded in collaboration with the Communists by Allendist exiles in Rome in 1973 to coordinate propaganda in Europe,] launched appeals for international solidarity, it did this by calling for the formation of an “anti-fascist front” after the example of the resistance against Nazi Germany.

Christiaens’s touching description of what was happening here is: “The idea of an anti-fascist struggle cultivated a common identity between Europe—East and West”. In plain terms, Pinochet’s image—which he was quite capable of damaging on his own—got blackened further with ludicrously false historical parallels, and the Soviets drew into their orbit a layer of ignorant, if well-meaning, people who attached themselves to the contemporary cause célèbre.

The Soviet “anti-fascist” posture had a very successful history: it was a primary recruitment tool during the heyday of ideological agents in the 1930s,3 and the indoctrination skills of the KGB’s predecessors were such that only a minority of recruits came to their senses when the Soviets signed a Pact with the Nazis to jointly start the Second World War a few years later. It was still working by the 1970s. Idealistic Westerners, most of them young, got swept up in Soviet agitprop structures, and Moscow was able to broaden the political warfare, as Christiaens (in his roundabout way) notes, to include campaigns against the pro-Western authoritarian governments of Antonio Salazar in Portugal, Francisco Franco in Spain, and the Colonels in Greece.

The Soviets were able to convince a sizeable number of people that, like Chile, these three Southern European States “and, by extension, Western Europe were a victim of U.S. colonialism and imperialism”, Christiaens writes:

Campaigns benefited from the growing focus on the Third World: they cultivated the connection between two peripheries of “middling development” that were seen as one “zone of fascism” and as victims of American imperialism, neo-colonialism, and multinational corporations.4

The effect was not just an increase in attention on Portugal, Spain, and Greece, in turn forcing the Western democracies, responsive to their people, to bring various forms of pressure on all of them—while the far grimmer conditions in the East got no such increased scrutiny. The campaigns energised the Communists within those three States. “Spanish, Greek, and Portuguese oppositionists at home and in exile entered … [the] Communist-led peace campaigns”, Christiaens records. “After 1973, East Berlin became a meeting point between Chilean exiles and Greek opposition networks”. It was in Athens, in particular, that a lot of the protests and riots were carried out under the banner of “solidarity with Allende”, though there were similar scenes in Madrid and Lisbon, and the Communists in all three countries utilised connections with the Soviet-supplied Chilean Leftist exiles to further their cause.

This nearly led to catastrophe in Portugal, but the army managed to pull things back from the brink and abort a Communist Revolution. Christiaens, however, clearly agrees with the Soviets, who called the Portuguese Communists’ defeat a “coup” and made “parallels between Chile and Portugal”, and agrees with the Allendist exiles who used “the Portuguese events” to “discredit the Eurocommunist idea that Western democracy and socialism were compatible and to legitimize their cooperation with Eastern European state socialism.” What will surely strike most readers is that Allende’s officials, faced with growing opportunities for socialism to succeed via democratic means, saw only disappointment that undemocratic socialism had failed again and further reasons to work more closely with the Soviet Union.

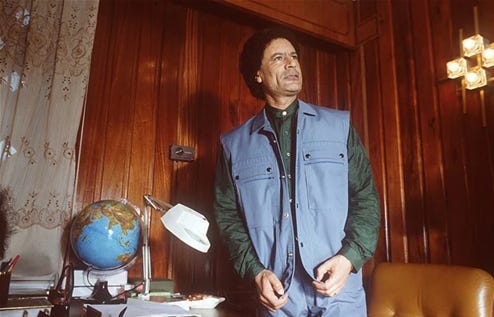

Christiaens documents the collaboration of the “human rights” campaigners against Pinochet with Colonel Gaddafi, an ally of the Soviets:

[T]he end of the Franco regime [in 1975] stimulated new campaigns against Pinochet. Galvanized by the refusal of the government of Adolfo Suárez to back U.N. action against Pinochet, from 1977 Spanish oppositionists rallied massive support in campaigns that united the Spanish Communist and socialist parties, Christian progressives, and trade union movements. With the support of the World Peace Council, Chile Democrático turned this national campaign into a global movement to isolate Pinochet and campaign on behalf of disappeared oppositionists in Chile. After a preparatory meeting in Benghazi in August 1978—financed by the Libyan Gaddafi regime—Chile Democrático staged a world conference of solidarity with Chile in Madrid in November 1978, which was attended by delegations of human rights groups, Social Democrats, Christian Democrats, and Communist Parties from all over the world.

The “Democratic Chile” activists were in Libya right around the time Gaddafi “disappeared” Imam Musa al-Sadr on behalf of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and Yasser Arafat, though there is no sign the activists raised this matter. It would have been impolite, not to say impolitic, given the funding arrangements, one supposes.

As galvanic as Franco’s death was to the Communist agitation against Pinochet, it was equally—as ever—a source of division, Christiaens notes:

The model of a “negotiated transition” undermined the mission of exiles and international solidarity campaigns, which had played only a minor role in the downfall of authoritarian regimes in Southern Europe.

The comrades had insisted “armed revolution” was the only way: some of the Chileans and many of the European activists whose real goal had been the end of despotism in Chile grappled with the fact this was not true; the Soviet loyalists who had seen Chilean despotism as a recruiting device for Communism rationalised the facts away. Allende’s Socialist Party split on the point: Moscow’s men stayed in East Berlin under the fanatic Clodomiro Almeyda, and the “renovated socialists” led by Carlos Altamirano left to Paris. Altamirano’s reassessment was remarkable so soon after he had been a coordinator of the Communist terrorist squads for the Allende regime.

The Soviet influence operation using Chile ran into some trouble at the end of the 1970s, says Christiaens. The example of peaceful European transitions sapped some of the momentum from the Third Worldist, violent revolution model, exemplified by Vietnam, and many Europeans concluded democratisation without carnage was possible. There was also some popular attention given for the first time to Dissidents in the Soviet Empire.

An aspect of the Soviets’ campaign to brand Pinochet a “fascist” that Christiaens brings out, which is seldom remarked upon, is the way it was used against the internal Soviet Dissident Movement. For obvious reasons, the Dissidents were generally not sympathetic to Allende’s Soviet-aligned government, and their refusal to be drawn into pro-Allende, anti-Pinochet activism was used as evidence of their “fascism”, legitimising their repression to domestic and certain foreign audiences. The Allendist Chilean exiles, dependent on the Soviet Revolution, and their “human rights” campaigner allies flatly refused to bracket their own cause with the Dissidents. A proposal in 1978 to mark the ten-year anniversary of the destruction of the Prague Spring and the Pinochet coup was vetoed.

The obvious discomfort the Dissident issue caused within the Communist front-groups advocating for the Chilean anti-Pinochet opposition and the “human rights” organisations that had gotten so close to them discredited these Soviet propaganda organs in the eyes of people genuinely concerned with unjust human suffering. And it got worse after the rise of Solidarity, the Catholic trade union, in Poland in 1980. The repression of Solidarity and the imposition of military rule in Communist Poland by Wojciech Jaruzelski in December 1981 was a clarifying moment for the Chilean exiles, as well as about them.

While Corvalán and Almeyda congratulated Jaruzelski for rescuing socialism, Altamirano went to see Solidarity leader Lech Walesa in Warsaw in early 1981 and after the crackdown months later accused Jaruzelski of a “coup” akin to Pinochet’s, partly probably out of genuine belief, but also as a very helpful way of countering Pinochet’s propaganda that all of his opponents were Soviet-loyal Communists.

The Chilean opposition elevated a young trade union leader, Rodolfo Seguel, as the “Chilean Lech Walesa”. Seguel was invited to Walesa’s Nobel Peace Prize award ceremony in December 1983, and Walesa called for the release of Manuel Bustos, a leading Chilean oppositionist, and even for Communist trade unionist Alamiro Guzmán. The Polish opposition, in its turn, found the “human rights community” and parts of the Left beginning to listen to it. The idea of a common anti-totalitarian struggle outside the Cold War binary garnered some support—and did so beyond the Left. The Roman Catholic Church and non-Communist trades unions had become the leading elements of the anti-Pinochet opposition inside Chile by the early 1980s, and the Roman Church was integrally associated with Solidarity. The symbol of this in some ways was when “Pope John Paul II visited Chile in April 1987: he ignored the official programme and met with political opposition leaders and with representatives of all trade unions.”

The stubborn fact was, however, the “majority of Chilean exiles” continued to side with the Soviet Union, writes Christiaens: they branded the “renovated socialists” who sided with Solidarity and the Soviet Dissidents “instruments of U.S. imperialism” and continued to advocate for terrorist revolution, which by the early 1980s had new avatars in the South African ANC—whose Soviet-backed anti-apartheid campaign was reaching its height—and the Nicaraguan Sandinistas.

The Soviet-orchestrated Sandinista triumph in Nicaragua in the annus horribilis for the West of 1979, six months after the fall of the Shah of Iran, gave Moscow Centre the mainland Latin American base for the export of Revolution they had been denied by Allende’s ouster.5 The Centre’s use of its Allendist assets after 1979 allows a glimpse of what would have happened if the Revolution had been completed in Chile. The Soviet-loyal Chilean émigrés “not only participated in the [Sandinistas’] armed struggle on the ground”, as Christiaens phrases it, but were “pioneers” in creating “solidarity movements” (a propaganda infrastructure) for the Sandinistas “in many European countries”.

The Soviets did not believe in State borders and the operational reality of their global terrorist-revolutionary infrastructure reflected this: the countries the Soviets colonised and the agents they recruited were not recognised in “national” categories, but merely as additions to the transnational movement, to be moved from front to front around the world as needed. (The Islamic Revolution in Iran, not coincidentally, works the same way at the present time.) A concrete case of this can be seen with Raúl Pellegrin (a.k.a. “Comandante Rodrigo” or “Benjamín”), a Chilean trained on the Soviets’ Cuban outpost. Pellegrin was sent by Moscow to Nicaragua in 1979 to assist the Sandinista Revolution, and then moved in 1983, under the banner of the “armed wing” of the Chilean Communist Party, to be part of the terrorist underground in Pinochet’s Chile, where he was killed in 1988.6

Christiaens records (in so many words) that the radical chic of the rekindled terrorist movements, especially in Latin America and Africa, fronted for the Soviets as ever by Fidel Castro and bolstered by the “anti-racist” element of the ANC’s messaging, combined with the re-energised “peace” movement in Europe, got the Soviet influence infrastructure within the West back online in the early 1980s.

The anti-nuclear activism of the 1980s was a notable success for the Soviet Union, with its definition of “peace” being to prevent (and later have withdrawn) NATO’s Cruise and Pershing missiles, which had been deployed in response to the Soviets stationing tactical nuclear missiles that were of absolutely no concern to the peaceniks in the Warsaw Pact States. In Britain, the leading campaign entity, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), was entangled with Soviet intelligence,7 which provided guidance and the secret funding that allowed the CND to function, passed to it by the KGB-controlled Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). It has to be said, there was that much secrecy about this: the overlapping membership was quite brazen—the CND secretary-general was a CPGB apparatchik as late as last year—and CND was embedded in the milieu Soviet front-groups like the WPC and World Council of Churches.8

Chile per se, then, somewhat faded from public view through the 1980s, even as the Communist influence networks the exiled Allendists had helped foster in Europe were in one of their most active phases. But Moscow Centre never lost sight of Chile. In 1987, Almeyda was clandestinely smuggled into Chile by the KGB and the East German Stasi. The “German Democratic Republic” (DDR) was frequently used by Moscow to interface with its terrorist assets, and the DDR had played a special role in rebuilding the Soviet infrastructure in Chile after the Pinochet takeover because, for reasons not completely clear, the DDR was the only Communist entity allowed to keep its Embassy open. Almeyda connected up with the Soviet-run PCC terrorist apparat inside Chile that Pellegrin had joined, and it continued functioning right to the end—its last political assassination was in 1991, after Chile’s democratic restoration and months before the Soviet Union went out of existence.9

In the end, as we now know, the violent revolutionaries were thwarted in their fantasies of bringing Pinochet down and adding Chile to the Communist camp. Democracy returned to Chile by the kind of Spanish transition they despised: General Pinochet staged a referendum on his continuing rule in October 1988, lost it, negotiated a civilian constitutional framework to replace him, and left office in March 1990. Similarly, the Communist attempts to capitalising on the post-Pinochet State’s weaknesses and disorders came to naught.

Proving once and for all that the Allendist alliance with Soviet Communism was not contingent—not that Christiaens ever says otherwise—even after Pinochet was gone and Chile’s democracy restored,

Many former exiles and new political leaders in Chile feared rather than welcomed the consequences of the collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe in 1989-1991.

Still, there was a human dimension to this ideological devotion. Almeyda was appointed Chilean ambassador in Moscow in 1991, shortly before the long nightmare of Bolshevism was terminated, and was soon joined by the longtime DDR administrator, Erich Honecker, who, wanted for high crimes in newly-reunified Germany, had made a run for it. Honecker’s former masters at the KGB sheltered him until the Soviet collapse, after which the new Russian government wanted him out. It was Almeyda who stepped in to offer Chile as a refuge for the (very) old criminal. There was a danger for a time that Honecker would face justice, but it passed, and in January 1993 he landed in Santiago, where he died as peacefully as liver cancer allows in May 1994, aged 81. The PCC organised Honecker’s funeral.

FOOTNOTES

Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin (1999), The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB, pp. 341, 427, 485.

Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin (2005), The World Was Going Our Way: The KGB and the Battle for Third World, p. 86.

The Sword and the Shield, pp. 84-85.

Christiaens mentions that what had in fact made General Franco and Salazar so tolerable to so many for so long was “[t]he association of the main Spanish and Portuguese opposition movements—headquartered in Eastern Europe—with the Soviet Union, as well as their Stalinist tendencies”, which “made them an unattractive cause”, even for European Leftists, but he does not dwell on this. Nor does the revived “memories of … Spain during the 1930s” trigger any introspection from Christiaens.

The World Was Going Our Way, pp. 116-125.

The Soviets’ “fraternal” PCC had established an “armed wing” as early as 1974, when the Party was in Allende’s government, and in exile it expanded. The PCC military cadre finally publicly announced itself in December 1983 as the Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front (Frente Patriótico Manuel Rodríguez, FPMR), named for one of Chile’s independence heroes. This nomenclature was part of the effort to disguise FPMR’s foreign loyalties and increase its local popularity by positioning it as “nationalist”—another tactic adopted by the Islamic Revolution with its Hizballah unit in Lebanon and other “external armies”. The claim from FPMR was that it was a separate organisation to, and merely aligned with, the PCC. Very few were convinced in Chile, and nobody in the U.S. took this seriously.

The first declared action of FPMR/PCC, which had been in Chile since 1980, was the abduction of a journalist, who was released on Christmas Day 1983. The FPMR carried out various robberies and bombings across Chile in early 1984, and twice—in January and March—the FPMR briefly took over radio stations to broadcast Communist propaganda. The first confirmed murder inside Chile by FPMR was in June 1984, when the “guerrillas” stormed a train in Linares. On 19 July 1985, the sixth anniversary of the Sandinista conquest of Nicaragua, the FPMR detonated a car bomb outside the U.S. Embassy in Santiago, murdering a bystander.

In 1986, FPMR began a wave of assassinations. In April 1986, FPMR murdered a senior official of the Independent Democratic Union (UDI), a Pinochet-supporting conservative civilian party. Pinochet himself was nearly killed by FPMR in September 1986, and there was another near-miss against General Gustavo Leigh in March 1989, during the transition to democracy, which fortunately was not derailed. Two other military-intelligence officials were not so lucky in 1989 and 1990, nor was the UDI’s founder, Jaime Guzmán, murdered by FPMR as he left a Catholic University after giving a legal lecture in April 1991. This was after the restoration of democracy that was the claimed goal of FPMR’s violent campaign.

FPMR was undoubtedly reasonably successful as a terrorist movement, though after the attempt on Pinochet its apparatus was inside Chile was devastated. But politically the result of FPMR’s activities was to remind Chileans of the dangers of the Communist Party. Frightened by the prospect that FPMR was going to use the protest movement to push Chile down the road that had been averted in 1973, the democratic opposition scaled back its attempts to pressure Pinochet for a quicker transfer of power in late 1986 and accepted El Tata’s terms for a more gradual transition to democracy.

See: Mark Ensalaco (2000), Chile Under Pinochet: Recovering the Truth, pp. 149-150.

The Sword and the Shield, p. 434.

Lung-chu Chen (2015), An Introduction to Contemporary International Law: A Policy-Oriented Perspective, p. 420.

See footnote 6.