Can We Support Regime Change Even If It Is Delivered by Donald Trump?

For those of us who regard Donald Trump as dangerous and contemptible primarily because of his rejection of America’s Imperial responsibilities around the world, recent events in Venezuela raise a number of questions.

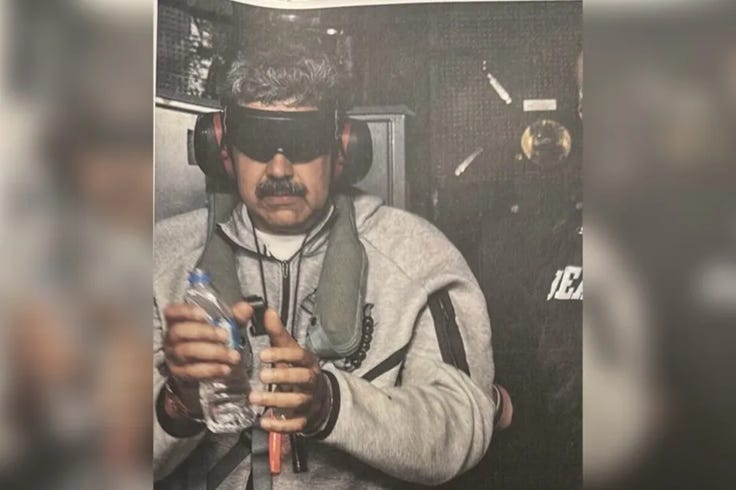

The first and most obvious question, as well as the easiest to answer, is whether we have been wrong all along. In a strictly military sense, Operation ABSOLUTE RESOLVE, the 3 January 2026 raid that deposed and captured Venezuela’s ruler,1 Nicolas Maduro, and transferred him to a prison in New York, was flawless.2 Not-coincidentally, this was the part that the Trump administration had the least to do with. The Generals whom Trump has menaced and the U.S. intelligence agencies Trump has compared to the Nazi secret police did their jobs. By contrast, as we shall see, everything the administration itself handled—from pre-intervention messaging to post-Maduro planning—has an unmistakeable air of shambles about it. This is hardly cause for a rethink about the nature of the Trump administration.

“Happy is He Who Keeps the Law”3

A question that must influence how we think about this is why Trump removed Maduro, and the administration has, in its most official documentation and presentations, put forward a legal rationale centred on the claim that Maduro ran a narco-terrorist apparatus which aggressed in various ways against America.

Trump added Tren de Aragua (TdA), a Venezuela-based transnational crime syndicate, to the State Department list of Foreign Terrorist Organisations (FTO) in January 2025, and in March claimed TdA was “perpetrating an invasion” and “conducting irregular warfare against the territory of the United States, both directly and at the direction, clandestine or otherwise, of the Maduro regime in Venezuela”.

The U.S. Treasury, in July, designated Cartel de los Soles, a “criminal group headed by Nicolas Maduro Moros”, as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist entity, which “provides material support to foreign terrorist organizations threatening the peace and security of the United States, namely Tren de Aragua and the Sinaloa Cartel.” Cartel de los Soles was designated an FTO under the same description in November.

In early September 2025, shortly after massing U.S. military assets became visible in the Caribbean, the U.S. started a series of airstrikes on vessels Trump said were operated by “confirmed narco-terrorists from Venezuela … headed to the US” with drugs. A month later, the U.S. was declared to be in “armed conflict” with these groups.

The unsealed indictment of Maduro makes reference to him having “partnered with narco-terrorists …, including TdA’s leader”, and at the press conference after Maduro’s apprehension, Marco Rubio—the U.S. Secretary of State and National Security Adviser, among other things—insisted that so far from an act of war, the U.S. had undertaken “largely a law enforcement function. … [A]t its core, this was an arrest of two indicted fugitives of American justice, and the Department of War supported the Department of Justice in that job.”

There have been all kinds of challenges to this case. Some doubt TdA is tied all that tightly to the Maduro government, though there is evidence in the other direction.4 It has been contended that Cartel de los Soles does not exist in any organised way, being merely a “slang term in Venezuela, dating back to the 1990s, for military officials who take bribes from drug traffickers”, which would appear to match the updated Trump administration language in the Maduro indictment.5

In targeting the drugs boats, the most publicly controversial aspect, the Trump administration initially claimed the strikes were preventing fentanyl being shipped to the U.S.,6 when the Venezuelan drugs trade mostly involves cocaine going to Europe. Accusations the strikes were illegal coexist with the reality that, whatever the scale of these shipments, the boats destroyed were trafficking drugs and they were operated by Maduro-backed cartels, their numbers padded out with paid “civilian” proxies.

This is all going to matter at the trial of Maduro. The Trump administration is essentially using the precedent of President George H.W. Bush’s regime change in Panama around Christmastime 1989, which ended with General Manuel Noriega, already indicted by U.S. courts for smuggling drugs into the U.S., captured, convicted, and imprisoned in Miami. Noriega tried to politically embarrass the U.S. by drawing attention to his prior relationship with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), but this was no defence against the solidly-evidenced legal charges. There is a potential for more than political embarrassment as the courts start sifting the details of the claims the Trump administration has made against Maduro. In terms of explaining why Maduro now finds himself facing trial, though, none of this legalese matters very much.

“They All Look To Their Own Way, Every One For His Own Gain”7

In the pre-intervention U.S. messaging, the legalism around the drugs issue was used in an openly pretextual way: legal pronouncements followed politico-military steps, they were not the cause of them. Indeed, the whole exercise in public diplomacy (or propaganda, if you prefer) over Venezuela has to be one of the strangest on record. It came from nowhere and disappeared for long stretches of time; it ostensibly signalled that U.S. action was coming, while telegraphing that Trump was reluctant to actually do anything. The pinprick boat strikes mostly showed there was no serious desire to stop the flow of drugs, and if anybody missed that hint, Trump’s full pardon in December of the former president of Honduras, Juan Orlando Hernández, let everyone in on the fact that being a Latin American ruler involved in drug-trafficking into the United States was not to put oneself beyond the Trumpist pale.

The whole thing had a feel of make-believe about it and seemed likely to follow the course of so many Trump “policies”: Trump had had a brainwave—or been talked into one—and would create the sense of a crisis up to a point, then walk away claiming victory, while things remained as they were before. And perhaps that was the original intent.8 On the record of this administration, we should have a detailed account of the decision-making “process” over Venezuela leaked to one of the newspapers by the end of the week.9 In the meantime, we can see some of the broad trends behind this.

There is clearly a faction in the administration of more “normal” foreign-policy Republicans—the most identifiable one is Rubio—who have long seen Maduro as a nuisance for strategic reasons (we will come to what those are in more detail in a moment). And there is a cadre of similar inclinations in the administration’s orbit who are associated with, or who appear on, Fox News, one of the key sources of Presidential information, and thus have some ability to persuade Trump.10 The impetus for the Venezuela policy comes from this faction. We cannot know (yet) exactly how Vice President J.D. Vance and his faction were outmanoeuvred, nor exactly what arguments the pro-interventionists used to win Trump over, but it would be most surprising if Venezuelan democracy and security in the Western Hemisphere had much to do with it.

Trump has certain specific fixations—like loving tariffs and despising NATO—within a general vision of geopolitics that is zero-sum and exploitative. Actions recommended to Trump in these terms have a chance of being implemented. Beyond that, the “policy” arguments that resonate most with Trump are those that promise him personal gain: financial if possible, otherwise political, namely looking strong and receiving adulation for “successes”.11 In this latter category, spectacle outweighs substantive effect, always. Trump’s penchant is for quick military operations and “deals”, preferably with a ceremony where Trump is centre of attention. In the second term, the psychological need to put his Democratic predecessors in the shade, especially Barack Obama, has become increasingly important, too, manifested most obviously in Trump’s obsession with being given the Nobel Peace Prize (a not-unimportant factor over Venezuela). Judging by Trump’s victory lap press conference on Saturday, the interventionists found an argument over Venezuela that combined several of these elements: oil.12

“That Which Has Been Is What Will Be”13

Trump did make reference to the “animals” of Tren de Aragua in his 3 January press conference, accusing them of being behind the savage rape and murder of the 12-year-old Texan girl Jocelyn Nungaray in June 2024, and said the Maduro regime had not only “emptied out their prisons” to send “their worst and most violent monsters into the United States to steal American lives”, but had sent people “from mental institutions and insane asylums”.14 However, that all came later.

The first thing Trump said after his five-minute “no nation in the world could achieve what America achieved yesterday” opening spiel was:

As everyone knows, the oil business in Venezuela has been a bust, a total bust, for a long period of time. They were pumping almost nothing by comparison to what they could have been pumping … We’re going to have our very large United States oil companies, the biggest anywhere in the world, go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure, the oil infrastructure, and start making money for the country.

Returning to the oil theme a few minutes later, Trump struck a different note:

Venezuela unilaterally seized and sold American oil, American assets, and American platforms costing us billions and billions of dollars. … They took all of our property. It was our property. We built it. … We built Venezuela oil industry with American talent, drive, and skill, and the socialist regime stole it from us during those previous administrations, and they stole it through force. This constituted one of the largest thefts of American property in the history of our country.

This line was repeated at another point, and, allowances made for rhetorical excess, it is not unreasonable. Many countries with oil under their territory would not be oil-producing States without the technology, infrastructure, and know-how provided by the West. It gives the West some “right” to not have those investments expropriated and the wealth generated using them diverted to fund anti-Western activity.

Trump went on in three separate bursts to place oil at the centre of his plans for what comes next in Venezuela:

We’re going to be running [Venezuela] with a group … We’re going to rebuild the oil infrastructure, which will cost billions of dollars. It’ll be paid for by the oil companies directly. They will be reimbursed … We’re going to get the oil flowing the way it should be. … [W]e’re going to run it properly, and we’re going to make sure the people of Venezuela are taken care of. We’re going to make sure the people that were forced out of Venezuela by this thug are also taken care of. …

[W]e have to rebuild their whole infrastructure. … It’s actually very dangerous. It’s, you know, blow-up territory. Oil is very dangerous. … [W]e’re going to be replacing it, and we’re going to take a lot of money out so that we can take care of the country. …

[W]e’re going to be rebuilding, and we’re not spending money. The oil companies are going to go in, they’re going to spend money, they’re going to, we’re going to take back the oil that, frankly, we should have taken back a long time ago. A lot of money is coming out of the ground. We’re going to get reimbursed for all of that. We’re going to get reimbursed for everything that we spend. … [T]his is a very big evening that took place last night. … So what’s going to happen with Venezuela, I think, over the next period of a year is going to be a great thing, and the people of Venezuela will be the biggest beneficiaries.

It is silly to pretend, as so many do, that it is inherently ignoble and illegitimate for the U.S. to be concerned about oil resources, especially on the scale of Venezuela, being controlled by a hostile government.15 Still, in an ideal world, explaining that strategic and national interest would not involve the U.S. President putting on the record quotes like, “we’re going to take back the oil”, and “we’re going to take a lot of money out”, even if the sentence finished “so that we can take care of the country”.

Trump said half-a-dozen times the U.S. was going to “run” Venezuela. Trump indicated that a Proconsul was going to be appointed, before suggesting—while inclining at Rubio directly—it would be more of a Mandatory Committee: “[Venezuela is] largely going to be [run] for a period of time [by] the people that are standing right behind me”.16 Expanding on the Mandate premise, Trump said: “we are going to run the country until such time as we can do a safe, proper, and judicious transition”. Trump’s reference to the U.S. being “ready to stage a second and much larger attack if we need to” suggests this contingency, initially formulated for the snatch-and-grab of Maduro, is being kept in reserve, along with (for now) the oil embargo, to overcome any barriers that arise to this “transition”. Asked about the role of American troops in this, Trump said: “we’re not afraid of boots on the ground if we have to have”.

If not quite a plan, then, there is the concept of a plan there: for the U.S. to administer Venezuela until such a time as there is a responsible governing elite to hand over to, and to foot the bill by reviving Venezuela’s oil industry. The problem is: the U.S. does not administer Venezuela. And the Venezuelan opposition that expected to take on the task in alliance with the U.S. was unceremoniously cast aside during Trump’s press conference.

María Corina Machado won the primary to become the unity candidate of the Venezuelan opposition before the July 2024 election, but she was banned from participation by the Maduro regime, so Edmundo González stood in her place—and blatantly won, with nearly 70% of the votes, despite Maduro’s attempt to falsify the results. Gonzalez has been recognised as the legal President of Venezuela by many Western States, including the U.S., ever since. Yet Trump made no mention of Gonzalez at all and said of Machado that he had not been speaking to her and, though she was “a very nice woman”, “she doesn’t have the support within, or the respect within, the country”. Venezuelan oppositionists were shocked: Machado “has gone out of her way to please [Trump], calling him a ‘champion of freedom’ [and even] mimicking his talking points on election fraud in the United States”. A sticking point in relations was Machado dedicating her Nobel Peace Prize to Trump, rather than refusing the Prize and insisting it was given to Trump.17

The woman Trump is choosing to do business with is Delcy Rodríguez, Maduro’s deputy and now acting president. Rodriguez was oil minister from 2020 to 2024, and showed some technocratic competence, which has endeared her to the Trump administration, bewilderingly when it is considered what else is on her resume. Rodriguez is, like Maduro, a socialist fanatic and Cuban agent; the devoted daughter of a Marxist terrorist who murdered an American; and she was head of the Cuban-dependent SEBIN secret police. Rodriguez initially struck a defiant tone in public, saying Maduro remains “the only president”, before she extended “an invitation to the government of the U.S. to work jointly on an agenda of cooperation”. Likewise Trump, while warning Rodriguez would “pay a very big price” if she “doesn’t do what’s right”, then said: “She is essentially willing to do what we think is necessary to make Venezuela great again”. Who knows what this portends.

Even if Rodriguez does play ball, it is unclear what she is being asked to do. Some officials briefed that “the Trump administration is leaning on [Rodriguez] to coordinate a negotiated transition”, with the threat of a second intervention and the oil embargo as leverage over her and the military-intelligence apparatus. Another “senior U.S. official” said Rodriguez may not be “the permanent solution”, but envisioned a much longer timeline for the Trump-Rodriguez partnership, seeing Rodriguez as reliable in advancing and protecting U.S. energy investments. Rubio split the difference in public, saying the U.S. wants a democratic transition and hopes the Chavista elite and military barons have got the message not to follow Maduro in defying America—but he scoffed at the idea of quick elections, said the opposition does not exist inside Venezuela, and that immediate U.S. priorities are expelling the Iranians and getting the oil industry working, so there are resources for the Venezuelan population, of course.18

What this underlines is the fundamental situation as it now stands: Trump has removed the man at the apex in Venezuela, while leaving the Chavista system, with its Cuban colonial overlords, entirely in place.19 And the question of intentionality cannot be avoided.

There is simply no way Cuba’s Intelligence Directorate (DI), which controls the Venezuelan intelligence-security apparatus top-to-bottom, was not aware of the Trump administration’s outreach to parts of the “Bolivarian” regime in the months before ABSOLUTE RESOLVE. Of all the CIA’s failures, its performance against the DI is perhaps the worst. Simply outclassed, the CIA got its first genuine Cuban defector in the 1980s, a walk-in obviously, who revealed that the four-dozen prior Cubans the Agency believed they had recruited were DI (or DGI, as it then-was) dangles. It is hardly one for the DI hall of fame, but it was the Cubans who defeated the “Bay of Piglets” challenge to Maduro in 2020, and much more impressively Cuba continues to this day to have great success in the spy-war within America. The U.S. should have been operating under the assumption that Rodriguez’s engagement with “intermediaries”, who apparently “persuaded” Team Trump that she was the socialist to put their chips on, had been detected by the DI, even if the talks had not been publicly reported in October.20

So, what happened? Did Rubio, who directed a lot of these back-channels and heretofore seemed to understand the Cuban dimension, really convince himself he was talking to Rodriguez and others independent of the Cubans? That the “incompetent, senile men” in Havana had missed this one, that the CIA spy in Maduro’s retinue had neutralised the DI, and Rodriguez would or could expel the Cubans once in power? Did the U.S. know they were really talking to Havana, which is why their interlocuters were not “disappeared”, and make a deal on that basis? Could that explain the pervading sense of simulation over all this and why Maduro was so exposed on the night, despite the public build-up of American forces? Or did everyone get lost in a game where Trump’s impulsiveness was not factored in properly?

Whatever is going on here, this is not regime change—at best, not yet.

Final Thoughts

The strategic benefits to the United States and the broader West of eliminating the Chavista government in Venezuela are plain. The official support the Caracas socialists provide to narco-terrorists is real and does threaten Western societies. More immediately, this behaviour fuels the drug wars and destabilises Latin America, adding to the refugee torrent from Venezuela itself because of the ruin of the economy and the repression—with direct consequences for the United States. Venezuela has, since the days of Hugo Chavez, pursued instability as a conscious program. The Communist FARC terrorists in Colombia, for example, were able to draw on extensive assistance from Venezuela.21 More broadly, Chavista Venezuela has been a source of subversion across the region, using the country’s oil wealth to assist despotically-inclined anti-Western revolutionary movements in coming to power in previously Western-friendly, law-governed States. The spread of socialism in the Western Hemisphere has increased the scope for Iran’s activities on the U.S. doorstep, the Chavistas having turned Venezuela into the premier regional base for the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC),22 which has by definition brought in Russia and, in a quieter way, China, too. Of these three enemy powers in Venezuela, all of them with a vote about where this goes next, the administration has spoken, infrequently and in passing, about just one, Iran.

Whether it is as host and facilitator of the anti-Western Tripartite Axis or emitting refugees on this scale, Venezuela’s problems ceased to be “internal affairs” some time ago. The behaviour of the Chavista government has impinged on the “rights” to peace and security of other States, and entitled them to take defensive measures, even in terms of “international law”, which has been the single most unhelpful prism through which criticism has been levelled at the Trump administration’s deposition of Maduro. Political warfare waged in this legal guise has become a really bad habit of late and it is completely counter-productive over Venezuela: it is not possible to even inconvenience U.S. officials, as has happened to Israel, and it misses the point. It makes its advocates “sound pettifogging and irrelevant” and, to the extent they have long records of supporting liberal interventionism, unprincipled and in some cases unhinged.

The issue at hand is that regime change in Venezuela is a sound proposal, combining strategic and humanitarian imperatives in a way that should be able to command broad support, and Trump has delivered a personnel change which he is speaking of as an oil grab. In their own minds, U.S. officials like Rubio may truly believe they working for different reasons and ends, and this framing is a cruel necessity to get their noble project past the Leader. But the political cost to the United States of this framing, by encouraging the most cynical global interpretations of her conduct, is serious in itself, and the attempts by officials to pursue under-the-radar policies at variance with Trumpian rhetoric have repeatedly proven a mirage.

Maduro is out of power and in a prison cell: unambiguously this is a positive.23 As to everything else that has happened, and what will happen, there is a deeply unsettling level of ambiguity. If the only change in “Cubazuela”, beyond its new face, is Americans working in the oil industry—perhaps after donating to some Trump family enterprise—that will be much less positive.24 If the Venezuelan opposition, which does have networks and vast support inside the country, concludes Trump has formed a condominium with the regime and seeks to take matters into its own hands, it could result in massacre or civil war. And if the Venezuela raid emboldens Trump to attack Greenland and/or Canada that would be catastrophic.25

FOOTNOTES

It may be pure coincidence, but Trump seems to have had a lot of flexibility in choosing the date of the Venezuelan raid and chose the sixth anniversary of his operation to kill IRGC Quds Force chief Qassem Sulaymani.

Spare a thought for the “experts” who said Venezuela’s Russian-provided air defence systems were impenetrable, albeit one need not worry about them too much. Many are resilient types who said the same in Syria for nearly fifteen years and summoned the fortitude, despite being proven comprehensively wrong, to say it again over Venezuela anyway.

Proverbs 29:18.

See this report for a detailed argument Maduro was closely associated with Tren de Aragua. Handle with caution since it is clearly an activist product, while simultaneously being aware that there are a lot of motivated claims on all sides.

There is also the overarching problem that journalists and analysts, from the Cold War through the War on Terror to the present, have shown a persistent inability to recognise how extensive a role State intelligence agencies play in terrorism.

The indictment reads: “NICOLAS MADURO MOROS, the defendant—like former President Chavez before him—participates in, perpetuates, and protects a culture of corruption in which powerful Venezuelan elites enrich themselves through drug trafficking and the protection of their partner drug traffickers. The profits of that illegal activity flow to corrupt rank-and-file civilian, military, and intelligence officials, who operate in a patronage system run by those at the top—referred to as the Cartel de Los Soles or Cartel of the Suns, a reference to the sun insignia affixed to the uniforms of high-ranking Venezuelan military officials.”

For those who became politically aware in the 2000s, and have been trapped in an internal doom-loop ever since where any hint of foreign intervention conjures “Iraq” as the “one-word answer”, there was a slightly vertiginous moment last month when, amid talk of military action in Venezuela to halt the flow of fentanyl into the United States, the White House designated the drug as a chemical weapon of mass destruction (WMD).

Isaiah 56:11.

Watching the pre-intervention Venezuela messaging, there was a strong sense—as with so much of the Trump administration—of reality television, or more precisely professional wrestling. Maduro had been cast as the heel, and was playing the part. Trump was confronting him and we had some specifics about what Maduro had done wrong—the drugs, the repression, sending migrants from Venezuela’s “prisons and insane asylums”—but these were expressed as pallid data points. It felt like a storyline where the reveal was still to come. Hints had been dropped that the claims Maduro rigged the 2020 election against Trump were making a come-back: top angles always work best when they rely on personal issues, and a deep backstory the audience has already encountered is even better. Still, however the story was resolved, it seemed everyone would get home safe.

One of the ways Maduro apparently worked himself into a shoot was by misunderstanding where the verbal lines were. Trash talking is obviously key to any good storyline, but it is—or was, before the era of comprehensive scripting—one of the areas of pro wrestling where the line between fantasy and reality gets blurriest. Promos are aimed at the characters, but the person playing the character can get legitimately upset if they think liberties are being taken that either make a mockery of their character or, worse, use the guise of kayfabe to attack them personally. According to The New York Times, Maduro’s miscue on this score was staging musical events where he claimed a commitment to “peace”, which “helped persuade some on the Trump team that the Venezuelan president was mocking them … So the White House decided to follow through on its military threats.” And really, anybody who participates in a singalong to John Lennon’s “Imagine” deserves everything they get.

(Suggestive that something like this occurred was Trump himself telling Fox News on 3 January that by the end Maduro “wanted to negotiate … and I didn’t want to negotiate”. Incidentally, in the same interview Trump said excitedly: “I watched [the raid], literally like I was watching a television show.”)

Trump said the plans for the Venezuela raid were not disclosed to Congress ahead of time because “Congress has a tendency to leak”, which it does. But the leakiness of his own administration is such that The New York Times and Washington Post had been informed about ABSOLUTE RESOLVE before it began.

For example, Jack Keane, a retired Army general and Fox News contributor, has played an important role in preventing Trump’s Ukraine policy being even more catastrophic than it has been.

The use of “policy” here should be understood as a shorthand, because the methods by which actions are ordered by Trump have little resemblance to the process of investigation, debate, and reflection, within a framework of constitutionalism and public interest, that usually attend an American Presidential decision.

The U.S. National Security Adviser (NSA) is among the officials who spend the most time with the President and by the nature of the job—the need to be trusted to intuit what the boss wants and why—they tend to understand Presidents best, and therefore produce the most insightful memoirs. (Probably the only rivals in this regard are speech writers.) John Bolton was Trump’s NSA from April 2018 to September 2019, and has explained Trump’s operational procedure this way:

[Trump] doesn’t have any kind of philosophy about national security or anything else that I can think of. He certainly doesn’t have a grand strategy. He doesn’t even do policy in the way we understand that term in Washington. He approaches pretty much everything on a transactional, ad hoc basis. … [H]e sees things through the prism of how his decisions affect him and whether they benefit him—he can’t tell the difference between his own personal interests and the national interest, if he even understand what the national interest is. He believes, and has said publicly, that he thinks if he has good relations with a foreign Head of State, then U.S. relations with that foreign State are good—as if the likes of [Vladimir] Putin and Xi Jinping and Kim Jong-un are affected by that kind of personal consideration. …

[Trump] envisions himself as a big guy, a big tough guy, [and] he likes other big tough guys. He listens to Putin, he listens to Xi … Information is not important to him. He doesn’t absorb it. … And he doesn’t particularly listen to the options. He makes up his mind, and then he wants to act on it. … He has basically no history in his mind. … [W]hat you get in a Trump administration [is] a crazy mixture of individual transactions, one by one which benefit Trump and maybe some of the people he’s dealing with, without any consideration of their larger implications.

This War on the Rocks piece is also a decent overview of how to think about Trump, particularly this: “There is a powerful impulse among the political and expert classes to map presidents onto familiar strategic categories. People in Washington like doctrines because they make the world legible. … The problem is that Trump does not actually fit any of these boxes, yet we’ve seen people call him a realist, Jacksonian, and isolationist, even fairly recently. Trump may be surrounded by people who have doctrines and ideologies, but … Trump himself does not have one when it comes to foreign policy. His views are not organized into a coherent theory of international politics, nor are they disciplined by consistent assumptions about power, interests, or restraint. This makes him unusually hard to read, especially if you have your own strong priors or believe Trump’s priors reliably predict future behavior.”

Oil has long had a special place in Trump’s predatory imagination. While Trump falsely claims he opposed the invasion of Iraq, he did later conclude he wished Saddam Husayn had been left in power. But, “once there”, said Trump referring to Iraq in 2013, the U.S. should have “kept the oil”. Trump was focused on Syria’s oil as early as 2012, a year into the rebellion. When Trump administration officials were scrambling to prevent the Leader withdrawing U.S. troops from eastern Syria in late 2019, it was to the oil card they turned. In the case of Venezuela, Trump has been “thinking” this way since 2017 at the latest, when he told his intelligence officials Venezuela is “the country we should be going to war with” because “they have all that oil”.

Ecclesiastes 1:9.

It may well be—indeed, many people are saying—that Trump is under the misapprehension that “asylum seekers” come from mental asylums, but at this press conference he had some quite exacting thoughts on the subject: “The reason I say both … A mental institution isn’t as tough as an insane asylum, but we got them both.”

That “war for oil” is an accusation on the Left—and increasingly on what passes for the Right—is bizarre. The underlying premise is that oil is not worth fighting over, and this is a flight from reality. There can be bad wars for oil, of course: Saddam’s annexation of Kuwait is an obvious case in point. But there are positive such ventures, too. A war that takes the oil resources of a State out of the hands of a gang of corrupt ideologues who use the income for anti-Western subversion, and gives control to a government that increases flows to the world market while using the revenue to benefit its population, is not a war that benefits America alone.

It is not wholly reassuring that even in theory, without the ability to impose a Proconsul on Venezuela, Trump is so unclear about who exactly will be playing that role and what their duties will be. If there was any one mistake that undid America’s plans for post-Saddam Iraq, it was not establishing firmly the mission for Mr. Paul Bremer before he landed in Baghdad.

A person “close to the White House” told The Washington Post flat-out that Machado accepting the Nobel Peace Prize was the “ultimate sin” that has doomed her in the post-Maduro situation: “If she had turned it down and said, ‘I can’t accept it because it’s Donald Trump’s,’ she’d be the President of Venezuela today.”

Trump officials and surrogates obviously deny this, and some of them tried to counter this report by laying out a series of political and prudential reasons why Machado was dumped in The New York Times this morning. But when reading the Times report, what is obvious is that a lot of the adumbrated problems were a result of the administration not engaging and coordinating with Machado; the problems did not cause the non-engagement. And the claim that trying to install Machado “could further destabilize the country and require a more robust military presence inside the country” than the alternative of working with the Chavista regime is, while definitionally true, baffling. Of course leaving the regime alone is less likely to cause instability than trying to replace it, but then why order a mission to abduct the ruler?

An easy way for the Trump administration to signal concern for the Venezuelan population would be highlighting the 900 political prisoners in Maduro’s jails and warning of dire consequences if they are harmed. It is instructive that not even Rubio shows any interest in this.

Rubio said in a television interview, “It was Cubans that guarded Maduro”, and Cuba’s Communist government would appear to agree, publicly claiming that thirty-two of its soldiers and other nationals were killed fighting for Maduro. Echoes perhaps of the Cuban Praetorians, acting at that time as cutouts for the Soviet Union, who failed to defend socialist tyrant Salvador Allende in Chile in 1973. Or not. Time will tell.

The Miami Herald reported in October that Qataris were (at least among) the intermediaries Rodriguez and her brother Jorge, president of the Venezuelan National Assembly, were using to communicate with Trump:

[The] initiatives in recent months aimed at presenting [the Rodriguez siblings] to Washington as a “more acceptable” alternative to Nicolás Maduro’s regime … [and] sought to persuade sectors of the U.S. government that a “Madurismo without Maduro” could enable a peaceful transition in Venezuela …

Qatar, which has close ties to the Venezuelan government and has been accused by U.S. officials of sheltering Venezuelan funds, played a key role as intermediary. All proposals were routed through … Doha, where … Rodríguez maintains “a significant relationship” with members of the Qatari royal family and hides part of her assets. …

According to sources, the proposals were presented to the White House and the State Department by U.S. Special Envoy Richard Grenell, who earlier this year met with Maduro at the Miraflores Presidential Palace in Caracas and helped secure the release of several American citizens whom Washington considered wrongfully imprisoned by the regime.

Interestingly, Grenell was described as “advising the administration to engage Maduro in negotiations to defuse the escalating diplomatic standoff”, suggesting again that the option of reaching some face-saving “deal” while dropping the whole Venezuela Question remained open until quite late in the day.

FARC: Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia).

Iran’s messaging over Venezuela was on display particularly via Ansar Allah (or “the Houthis”), the IRGC’s Yemen-based unit, as explained by Fatima Abo Alasrar. Of note:

Iran, Lebanon, Yemen, and other Axis countries were saturated with language that elevated Maduro as a symbol of resistance to the West …

On December 2nd, 2025, a full month before American helicopters descended on Caracas, the Houthi-controlled Saba News Agency published a 21-page strategic analysis paper on Venezuela. … The paper states explicitly that the Venezuelan crisis is no longer an internal political dispute, nor a counternarcotics operation, but part of a wider confrontation between Washington and the “rising powers, China and Russia, in the geopolitically sensitive space of the Caribbean.”

In Houthis’ media telling, Venezuela survives because the military remains unified with the state, the opposition holds social presence but lacks institutional capacity, and external patrons such as China, Russia, Iran can provide alternative financing and trade networks that blunt the sanctions regime. The parallel to Yemen is left unstated but unmistakable. …

For Iran, the relationship isn’t merely rhetorical. Venezuela has been a sanctions-evasion partner since at least 2020 … This is the “grey zone” the Houthi research paper describes: states operating between American power and emerging alternatives, using the overlap between Russian, Chinese, and Iranian networks to create maneuvering room. …

When Hezbollah links Venezuela to “Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Iran,” it’s not engaging in rhetorical excess but it’s constructing a unified field of what is essentially an American threat to them in which all resistance is the same resistance.

Many American allies have been wary of being drawn on Maduro’s apprehension. Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky handled it the best, saying while laughing somewhat uncomfortably: “Well, what can I say? If it is possible to deal with dictators like that, just like that, then the United States of America knows what to do next.”

While cryptocurrency is often accused of having “no” utility, this is most unfair. The criminal community has demonstrated a dazzling array of uses. For Trump personally, this has involved setting up a series of crypto mechanisms that allow foreign powers to bid for his attention and favours. Inevitably, there is a jobs for the boys dimension. Over Venezuela, this appears to have involved someone involved in the raid to grab Maduro leaking information to a friend, who then made $400,000 by placing a series of bets on Polymarket predicting Maduro’s downfall about two hours before Trump gave the order. In the stock market, this is called “insider trading” and is quite a serious crime; the crypto industry is free of such oppressive regulation.

Within hours of Maduro being arrested, Katie Miller, the wife of Trump’s deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller, had put out a tweet with Greenland covered in an American flag and the single word, “SOON”. Trump was asked about this shortly afterwards and waffled about the post, before saying: “But we do need Greenland, absolutely. We need it for defence.” Denmark took it seriously enough to officially protest, noting that threatening NATO allies is no way to behave and an actual invasion would destroy he Alliance. Britain spoke in similar terms in giving public backing to the Danes. After this, Trump returned to the point yesterday. “I think that Greenland is very important for the national security of the United States, Europe, and other parts of the Free World”, Trump told NBC, adding he had “no timeline” for military action, but that his intent was “very serious”.

Trump says many things designed to shock or which he otherwise does not mean in any material sense. But Trump also says many things he really is serious about which get discounted because they seem so outlandish. It is impossible to know which category invading Greenland falls into, but Trump’s preoccupation with the idea means it cannot be assumed he is trolling, and anyone relying on the officials in this administration to prevent Trump acting recklessly is madder than they are.

An interesting and insightful piece. Whilst I am more supportive of the Trump administration (mainly due to the hope that Trump can somehow help to defeat the reactionary plans of Labour in the UK to destroy freedom of speech and because his administration is more likely to be supportive of European states that pursue policies of restricting immigration), I am also concerned about what happens next. It does feel as if some of these foreign policy adventures are motivated by a need to achieve some "victories" whilst Trump's domestic agenda is getting bogged down by lawfare.

With the Right and the whole "war for oil" slogan, I have often felt that one of the greatest weaknesses of those on the Right who opposed the war in Iraq was their inability to create their own comprehensive narrative to explain their opposition to it. Instead, it feels as if the anti-war narrative of the Left was just accepted whole-heartedly by many on the Right, which has since then helped to spread anti-Semitism and Third Worldism among the Right.