What Happens Now America Has Eliminated Another Islamic State “Caliph”?

Celebrate the demise of Amir Muhammad al-Mawla (Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi al-Qurayshi), but don’t expect too much from it

Nothing in Syria stays secret for long and last night, about 22:30 British time on 2 February (just after midnight 3 February Syria time), it became clear that the U.S. had launched a ground operation in Syria, of which there have only been a handful since the first in May 2015.

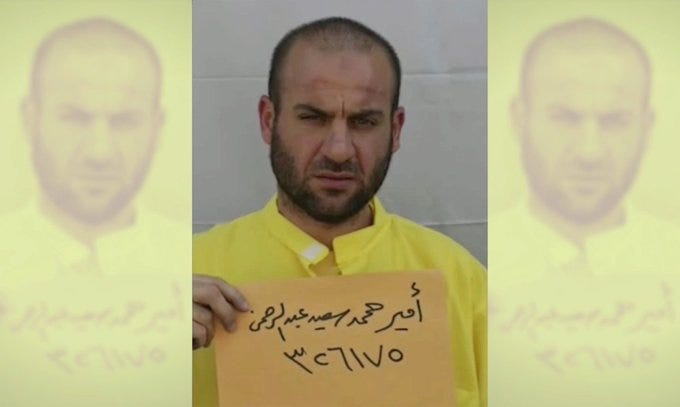

After much speculation, President Joe Biden announced in a brief statement just before 13:00 British time today that in the early hours of 3 February 2022, the Islamic State (IS) leader or “caliph” Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi al-Qurayshi, whose real name is Amir Muhammad al-Mawla, had died during an American raid on his hideout. Al-Mawla had been announced as the IS leader on 31 October 2019, after his predecessor, Ibrahim al-Badri (Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi), died four days earlier, on 27 October.

There are some obvious similarities between the raids that killed Al-Mawla and Al-Badri: both were found, unexpectedly (albeit less unexpectedly this time), in Idlib province in north-west Syria—Al-Mawla in Atma and Al-Badri about fifteen miles to the south in Barisha—and both killed themselves by detonating a suicide vest, rather than being killed or captured by U.S. special forces.

In Biden’s statement on the raid, he added only two points worth highlighting:

First, Al-Mawla blew himself up on the third floor of the safehouse in a massive explosion that murdered his own family, whom he had kept with him as human shields. For everything that IS and other jihadists say in public about the cruelty and ruthlessness of the United States, their actions show they know better: just as IS’s infamous spokesman Taha Falaha (Abu Muhammad al-Adnani) kept himself surrounded with children for weeks before his end in 2016—with the CIA only striking when Falaha ventured out alone—so with Al-Mawla, he knew the presence of his wife and children would prevent the U.S. launching airstrikes. Instead, the U.S. risked American lives to try to avoid civilian casualties.

Second, Biden made a reference to this operation being prepared “over the course of many months”. “It was months ago the US learned the leader of ISIS was living [in Atma]”, according to officials speaking to CNN. Other officials told NPR that the planning for this specific operation began “more than a month ago”, with the final go-ahead given by Biden on 1 February.

The significance of this is that it means Al-Mawla was in the sights of the Americans before 20 January, when IS began its attack on the Sinaa prison in the Ghwayran area of Hasaka city. It seems very likely that the timing of the raid to kill Al-Mawla is related to the attack on Al-Sinaa, which creates two options: (1) the U.S. had tracked Al-Mawla before the prison break, and decided to strike after the prison break to prevent IS moving its leader to safety; or (2) Al-Mawla somehow “surfaced” to U.S. intelligence after the prison break, perhaps because he attempted to move.

The Biden statement and the controlled leaks from his officials strongly point at option (1), but that creates another question: Since the Ghwayran prison attack last month was a replica of an attack that was thwarted in November 2020, how is it that the U.S. did not notice the rebuilding of such a large and deadly network in one of the key cities it nominally controls in Syria, while simultaneously having such good coverage of another area in northern Syria that it does not control as to be able to pinpoint and eliminate the caliph?

There are any number of conceivable answers to this; it would simply be useful to know which one was true. Biden chose to name-check for praise the U.S. partner force, the “Syrian Democratic Forces” (SDF), but the reality is that the Ghwayran episode has highlighted some very deep-rooted issues with the “SDF” regime, a serious problem since the U.S. is relying on that regime for its presence in Syria. Perhaps as pressing and rather knottier is the problem of IS having a refuge for its senior leadership in Idlib, a province nominally controlled by the Al-Qaeda-derived Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and for which Turkey has accepted notional responsibility. With the exception of these unilateral U.S. operations as and when intelligence presents itself, it is difficult to think there is a “solution” to the IS problem in Idlib—or the HTS problem, if it comes to that.

WHO WAS AL-MAWLA?

Al-Mawla had, before he became the caliph and took on the name Abu Ibrahim, been known as Haji Abdullah al-Afri and possibly as Abdullah Qardash, though this latter kunya was apparently challenged by Iraqi officials.

This is what was known of Al-Mawla’s biography at the time of Al-Badri’s demise:

[T]he U.S. Treasury released a Rewards for Justice notice … [that] described Al-Mawla as “a religious scholar” with ISIS since the time it was called Al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia (AQM) between 2004 and 2006, who “steadily rose through the ranks to assume a senior leadership role”. Al-Mawla is “one of ISIS’s most senior ideologues,” Treasury went on, and in this role he “helped drive and justify the abduction, slaughter, and trafficking of the Yazidi religious minority in northwest Iraq and is believed to oversee some of the group’s global terrorist operations.” …

According to Al-Arabiya sources, Al-Mawla was born in 1976 in Tal Afar (hence “Al-Afri”), a town west of Mosul that was a hot-bed of extremism long before the fall of Saddam Hussein, producing some of the most important ISIS operatives. Indeed, it seems Al-Mawla was close to the most important known figure of the underground jihadi movement in 1990s Iraq, Abd al-Rahman al-Qaduli (Abu Ali al-Anbari), the caliph’s deputy until March 2016. Al-Qaduli was born in Mosul but spent most of his time in Tal Afar. …

Al-Mawla’s position at the head of the Delegated Committee, the ISIS executive body …, [means] he is well-placed to take the leadership.

The work Feras Kilani has done corroborated much of this. Al-Mawla graduated with honours in 2000 from a Quranic studies course at university and then did his eighteen-months military service. Al-Mawla thereafter joined the jihadist underground before the Saddam regime came down, specifically joining Al-Qaduli’s jihadist outfit. In January 2007, Al-Mawla gained a master’s degree in Islamic studies and was soon afterwards, now known as “Professor Ahmad” (Ustaz Ahmad), an IS judge in Mosul. Kilani reports that in this period Al-Mawla began preaching in the Furqan Mosque in Al-Ba’th neighbourhood in western Mosul, where his father had once preached. Al-Mawla was arrested on 6 January 2008 and imprisoned at Camp Bucca, where he spent a year; by 2009, he was out.

Al-Mawla’s prison term has become a considerable source of debate and controversy because the U.S. government released three tactical interrogation reports (TIRs) involving Al-Mawla (see here, here, and here) in September 2020 and then released fifty-three more in April 2021. Most of the TIRs date to January and February 2008, though there are a couple from the summer of that year; there are heavy redactions in places, notably the last TIR dated 2 July 2008, which is completely blacked out, and ten TIRs did not see the light of day at all. The headline—literally: it was reported globally—was that Al-Mawla appeared to be “a prolific—at times eager—prison snitch”. One specific IS operative it seemed Al-Mawla had given up was, Mohamed Moumou (Abu Qaswara), a very senior IS official when the U.S. struck him down in October 2008.

My own view is that this was an attempted black propaganda operation by the U.S., and that anything Al-Mawla gave away was controlled, much more on the model of Manaf al-Rawi, the Baghdad wali (governor) arrested in 2010, an apparently cooperative turncoat, yet someone who continued the information operation that protected Al-Qaduli, whom the Americans had in custody without ever knowing it. Al-Mawla at one point, for instance, claims to be a Sufi, and effectively disclaims membership in IS entirely on that basis, yet at another moment claims to have only joined IS in February 2007 and risen to become deputy wali of Mosul in a couple of months. It would be notable if Al-Mawla really had joined IS when it seemed to be losing. However, when setting Al-Mawla’s self-contradictory testimony against the independent reporting that Al-Mawla was in the Iraqi jihadist milieu by 2002, it is clear how one has to weight the evidence. That Al-Mawla is speaking at such length to the Americans is certainly interesting, but not, I submit, for the substance of what Al-Mawla is saying. Rather, what is interesting is the way Al-Mawla is—in my judgment—dissimulating and even probing his enemies while appearing to cooperate.

Upon release, Al-Mawla, like so many others, went straight back to jihad. During the time IS held a statelet, Al-Mawla was something akin to the “justice minister”, reports Kilani, and was engaged in training clerics at Al-Imam al-Adham College in Mosul, where Al-Mawla worked closely with Al-Qaduli. By Kilani’s account, Al-Mawla was with the faction of (mostly foreign) hyper-extremists who pushed Al-Badri to implement the genocide against the Yazidis and enslavement of the survivors in 2014; interestingly, Al-Qaduli and most of the senior Iraqis in IS apparently opposed this, if only on prudential grounds that it might spark sectarian reprisals against their families.

Al-Mawla’s support for, and involvement in, the Yazidi genocide was something Biden mentioned again today and the U.S. government has put it in sanctions notices and other public documents; it is possible this is one of those bits of information that has just been repeated so often it has become canonical, or else it might be based on more solid evidence, probably derived from intelligence, which is what makes the U.S. so coy about spelling out how it knows what it knows.

Kilani argues that as the tide turned against IS, with Al-Qaduli’s long-time friend, Fadel al-Hiyali (Abu Mutaz al-Qurayshi), and then Al-Qaduli himself being killed in 2015-16, Al-Mawla was in effect last man standing, and was kept away from battle by Al-Badri because Al-Mawla’s academic study of Islam made him an ideal candidate from among the survivors as successor. By the end of Al-Badri’s reign, Al-Mawla had already it seems taken over significant parts of the day-to-day running of IS. Al-Mawla’s own reign was distinctly unglamorous, but he retained control over 10,000 jihadists and this kind of data crunching does not really capture the extent of IS’s recovered influence.

WHAT NEXT?

In terms of the impact on IS, Al-Mawla’s death will surely cause some short-term disruption, and it is possible that there are further IS officials to fall: the IS spokesman, Abu Hassan al-Muhajir was killed hours after Al-Badri, clearly brought down by the same breach of security that had undone the caliph. Likewise, in both 2007 and 2016, the spokesman and media emir were killed or captured near-simultaneously. The overall impact will be minimal, however: the succession will be smooth and swift, and the new leader will follow along a program that IS has many times explained over the last two decades.

There are the traditional requirements for the caliph, like being from the line of Quraysh, and some things one can surmise about the characteristics of the next caliph: more likely to be a religious and/or judicial figure than a military one; probably a “legacy” member; unsurprising if he has an administrative background. But as Craig Whiteside has pointed out, “[IS has] achieved what many organisations struggle to achieve, by developing a core of humans who think enough alike that policy making and strategy execution become much simpler when compared to, say, the United States government and its bureaucracies that are more interested in fighting each other than a common foe.” For this reason, among others, speculation about the exact person to replace Al-Mawla is essentially pointless; it is also hopeless.

It is not only hopeless in the sense that the list of known candidates to become caliph when Al-Badri killed himself has been considerably thinned down. For a start, two people on the list were already ineligible: it transpired that Abu Ubayda Abd al-Hakim al-Iraqi was in fact Wael al-Ta’i, better known as Abu Muhammad al-Furqan, the media emir who had been killed shortly before Falaha in 2016, and Abd al-Nasir Qardash, whose real name might or might not be Taha al-Ghassani, was already in custody, not that we would know it for another eight months or so. In May 2020, Moataz Numan al-Jaburi (Haji Tayseer) was killed, and, in October 2021, Sami Jassim al-Jaburi (Haji Hamid) was arrested. (There is at least one addition to the list: Bashar Khattab al-Sumaidai, a.k.a. Haji Zayd, the head of the IS judiciary.)

It is hopeless in the sense that three times now—in 2006, 2010, and 2019—IS has chosen a complete unknown as leader. After the IS founder, Ahmad al-Khalayleh (Abu Musab al-Zarqawi), was killed in 2006, the IS movement managed to keep the U.S. guessing for a time about whether his successor, Abu Umar al-Baghdadi, was even a real person (he was, a former policeman named Hamid al-Zawi). Al-Badri did not make a proper speech for two years for security reasons; as it happened, Al-Mawla never got to make one.

None of this mattered. As a pair of scholars succinctly summarised after last time, “The Islamic State facilitates a transfer of legitimacy from the old leader to the new, protects the identity of the leader for as long as it can, and begins the posthumous elevation of deceased leaders into the movement’s folklore.”

The rebuilding work that has clearly taken place for IS at the centre (Iraq and Syria) under Al-Mawla, as well as in the “foreign” branches, particularly Africa and Afghanistan, plus the “spectacular” attacks like those at Kabul Airport and the Sinaa prison, will soon be utilised in narratives that, while containing truths, imbue Al-Mawla’s life with a quality of myth as a man who held the line and kept the faith in a time of darkness, leading to great things. Depending on who—as opposed to how many—IS released from Sinaa in this BREAKING THE WALLS operation that was one of the last things Al-Mawla ordered and the effect that ends up having, these myths will seem more or less credible, and thus be more or less potent in, first and foremost, ensuring that the office of caliph retains a legitimacy and majesty, and can, secondarily, inspire and mobilise jihadists.

In the struggle with the Islamic State over the last twenty years, a recurring problem has been the West judging the conflict by metrics—the amount of territory IS holds, say, or the number of leadership losses—that are oftentimes actively misleading about the strategic decisions IS makes and the true extent of its financial infrastructure and the socio-political influence it wields. As a thing in itself, there is everything to celebrate in Al-Mawla’s destruction; revenge has been taken on someone who took the lives of countless innocent people and is responsible for things far worse than murder. More caution is needed about what this means, though, since we have been here before.

UPDATE (4 FEBRUARY)

While Idlib might seem like hostile terrain for IS, the group has been able to establish networks in the province because the mass-displacement of people by Bashar al-Asad’s regime—supported by Russia and Iran—has swelled the population in Idlib to three million, more than double what it was before 2011, and the newcomers are from all over Syria and beyond. In other words, it is no longer strange in Idlib for there to be strangers, allowing IS’s operatives to pass unnoticed.

UPDATE (6 FEBRUARY)

Jenan Moussa of Akhbar al-Aan reported that the house Al-Mawla was killed in had been rented starting on 6 March 2021, by a Syrian IS operative, who used the name Mustafa al-Shaykh Yusuf. Yusuf initially signed for the lower two floors of the compound, and moved in with two women, believed to be his wife and sister. A handwritten note on the contract, dated 20 March 2021, shows Yusuf expanding his tenancy to include the top (third) floor. U.S. intelligence would later reveal that Yusuf had used the kunya Abu Ahmed al-Halabi. Al-Mawla moved to Idlib shortly after this, sometime around late March 2021. Yusuf was killed in the raid that killed Al-Mawla, according to Moussa.

By coincidence—or not—the compound in which the previous caliph, Ibrahim al-Badri (Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi), was found had been rented by a man variously identified as Abu Mohammed al-Halabi and Salam Haj Deeb; it is not clear whether Abu Mohammed and Deeb are the same man (IS operatives use multiple names), nor is it clear if either name refers to Yusuf, and it remains very murky what relationship the man who purchased Al-Badri’s safehouse in Idlib had with Al-Qaeda’s Hurras al-Deen branch.

Adding a further layer of intrigue, it is possible that Yusuf was IS’s official spokesman, Abu Hamza al-Qurayshi.

UPDATE (10 FEBRUARY)

The picture of Qurayshi that emerged from the surveillance is that of a hands-on commander who was firmly in charge of his organization … “He was very much in command,” a senior Biden administration official said of Qurayshi …

Sometime [around March 2021], Qurayshi took up residence in the modest third-floor apartment with a rooftop view of fields and olive trees. To evade his many pursuers, the Islamic State leader adopted rigorous security protocols, U.S. officials said. In addition to banning cellphones and Internet connections, he relied on couriers … But that arrangement ensured visits by strangers to Atma …

The officials said Qurayshi — distinctive because of the leg, which CIA analysts think was amputated after injuries suffered in a 2015 airstrike — was sometimes spotted outside the house, or when taking brief strolls through the olive trees. Word eventually made its way to informants who work for the Syrian Democratic Forces …, current and former U.S. officials said. Intensive surveillance began immediately afterward, with Kurdish watchers following the arrivals and departures of armed men who trudged upstairs to meet with Qurayshi.

The surveillance was expanded to include some of the U.S. government’s most sophisticated remote cameras and sensors, most of them on drones operated by the Defense Department, the officials said. … By late September [2021], U.S. Special Forces teams had begun training for a raid on the house … Those preparations entailed regular rehearsals with models, including a full-scale mock-up of the dwelling … An airstrike against the house was considered but quickly ruled out … On Dec. 20, the president met with his national security team to formally approve the operation against Qurayshi, officials said. …

By 1 a.m. local time on Feb. 3 — 6 p.m. Feb. 2 in Washington — helicopters carrying two dozen members of the elite force were hovering over the house in Atma.

A crucial piece of this is confirmation that the “SDF” did play an important role in leading the U.S. to Al-Mawla.

In an event like Al-Mawla’s killing, every actor tries to get in on the political spoils. To give only two examples: surrogates of Turkey and HTS have tried to get into circulation the idea that they had some role in bringing down the caliph.

For Turkey, the intention is both to deflect blame for another IS caliph turning up in an area they have accepted some kind of responsibility for, and to deny the “SDF”—the cover name under which their sworn enemy, the PKK, operates in Syria—any credit for this operation, in hopes that over time the U.S. can be decoupled from the “SDF”.

For the “SDF”, this outcome is a timely one, since questions had been asked of them after the IS attack on the prison in Hasaka in January 2021 released hundreds of IS jihadists, and the “SDF” leader himself conceded that the “SDF” had failed grievously in the run-up. Those questions will now either go away, at least in the public discussion, or will at least be balanced (and thus minimised) by mention of the “SDF” role in getting Al-Mawla.