Iranian Information Operation Against Syria’s “Interim” President Goes Wrong

What the leaked documents really tell us about Ahmad al-Shara’s life before the Syrian rebellion.

Two weeks ago, it became clear that Iraqi Prime Minister Muhammad al-Sudani would invite Syria’s “interim” president, Ahmad al-Shara, to the Arab Summit in Baghdad on 17 May. The Islamic Revolution that rules Iran also dominates the Iraqi State and installed Al-Sudani. There are tactical differences in any movement, however, and Tehran was evidently displeased with this move by Al-Sudani. Within twenty-four hours, the Iranians had leaked documents related to the time when Al-Shara was imprisoned in Iraq as an operative of the Islamic State movement. The purpose was to portray Al-Shara as a terrorist steeped in Iraqi blood, and in immediate political terms the Iranians got what they wanted. Shi’a Iraqis were furious, Shi’a political leaders released statements condemning the invitation, and there were calls for Al-Shara to be arrested if he set foot on Iraqi soil, culminating in Al-Shara’s trip being cancelled. Over the long-term, though, Iran’s information operation has weakened its position because the leaks do not quite show what the Iranians and their surrogates claimed.

AL-SHARA’S FATHER AND EARLY LIFE

During Al-Shara’s first interview with a Western media outlet, America’s Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), in 2021, he spoke at some length about his father, Husayn Ali al-Shara, and with good reason. Husayn has had an interesting life in his own right—he is still alive—and has clearly had a lasting impact on Ahmad, in ways conscious and unintended.

Husayn was born to an elite family in the Golan Heights in 1946, but became a militant pan-Arabist. Husayn fled Syria after the Ba’thist takeover in 1963 and spent the rest of the 1960s in Iraq, which was also under the Ba’th by the end of the decade. In that time, Husayn had been involved with the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and its war on Israel. Husayn returned to Syria in 1969 and after the “corrective coup” in 1970 was reconciled enough with the new regime of Hafez al-Asad to be given a job in the State oil industry as an economist and instructor. Husayn began his career as an author with two books on the politics of oil in the mid-1970s.1 Husayn resigned from the Syrian oil sector in 1979, taking a job at the Saudi Ministry of Energy as an economic researcher. This was at a moment of epochal significance for Saudi Arabia and the whole region.

Iran, the avatar of modernism and development, fell to an Islamic Revolution in January-February 1979 that drowned the country in blood and immediately began exporting its malady. One of the aftershocks was convincing the conspiracy-addled leaders of Moscow Centre that containing the contagion required the Soviets to conquer Afghanistan,2 the beginning of a decade-long war that triggered the first jihadist foreign fighter flow.

The intellectual and practical infrastructure for the pan-Islamist movement that created the “Arab-Afghans” had been building through the 1970s, concentrated in the Saudi Kingdom, where Islamist refugees, most of them Muslim Brotherhood operatives from Egypt and Syria, had gathered, and been allowed to focus their activism on global Muslim causes.3 This cadre had also begun fusing Ikhwani revolutionary political methods with Salafist/Wahhabist doctrines,4 a key step on the road to the creation of the “Islamic Awakening” (al-Sahwa al-Islamiyya) and the crystallisation of the jihadi-Salafist movement in the 1990s,5 two major challenges to the Saudi monarchy. This was in the future, though.

The immediate worries for the Saudi government were Ayatollah Khomeini’s Revolution externally and the potential it would activate “extremist” dissent internally, a risk highlighted in Saudi minds by Juhayman al-Utaybi’s apocalyptic sect occupying the Grand Mosque in Mecca for a fortnight at the end of 1979. Both concerns pushed the Saudi government to abandon any reformist ethos and lean on Wahhabism for legitimacy, domestically and abroad. Saudi Wahhabi missionaries, already active in the region and beyond with the tacit support of the U.S. to blunt the spread of Communism,6 now went into overdrive to counter the Iranian Revolution, drawing the Saudis into some very dubious enterprises, notably in Bosnia, albeit Iran did worse even there.

This was the atmosphere in which Ahmad Husayn al-Shara was born in Riyadh in 1982. His father, Husayn, never deviated from his convictions, even if he was hemmed in when it came to public expression of his views in his columns.7 But it is impossible to believe Ahmad spending his formative years in the Saudi Arabia of this era had no impact on his subsequent trajectory.

Husayn moved back to Syria and Ahmad saw it for the first time in 1989. The family settled in the Mezzeh area of Damascus, an “upscale” area as Al-Shara told PBS: “It had middle and wealthy classes, and we were considered middle class. … [T]he neighbourhood … was largely liberal. The Islamic leanings were weak, almost non-existent. So the environment I lived in was not directing me or pushing me towards the Islamic trend.” In the home, Al-Shara’s father continued to preach pan-Arabism.

Yet, with every social cue and incentive pointing him towards liberal and secular ideologies, Al-Shara reacted against it from an early age. He was primed with the Islamist perspective, seeing his father’s prioritisation of Arabs over Muslims as the wrong way around. “[M]y father and I were not much in agreement regarding our ideas”, Al-Shara said on PBS, while adding: “for sure he influenced us. The love of Palestine, for example, … this was planted inside our home around the clock.” Ironically, by Al-Shara’s account, it was to be the Palestine cause that he and his father shared that hardened the division between them.

AL-SHARA’S JOURNEY TO JIHADISM

Al-Shara said in the PBS interview that the outbreak of the Second Intifada in late 2000, the terrorist war launched by the PLO (and supported by HAMAS) against Israel, “strongly influenced” his turn to radicalism. Still, at this point, at 18-years-old, Al-Shara says his “thinking” was “spontaneous” and “innate”, “not politicised or directed”. Al-Shara goes on: “Then someone advised me to go to the mosque and pray at the mosque and to commit to praying at the mosque”, which he did. Under the influence of “a virtuous shaykh”, Al-Shara found “that life has another meaning, different than the pure worldly meaning … So I started searching for this truth … in God Almighty’s book, the Holy Qur’an, [and] in the practices of the Prophet.”

When the September 11 attacks hit, Al-Shara was a year into his religious instruction, but in the interview twenty years later he downplayed the significance of this Islamist influence: “anybody who lived in the Islamic world, in the Arab world at the time who tells you that he wasn’t happy [on 9/11] would be lying to you”. Al-Shara quickly added, “I hope my words don’t offend innocent people who might be killed in any place … I don’t encourage it [feeling happy about 9/11]. But I try to explain, objectively, the state of the region at the time, and … I’m explaining my own feelings and the feelings of people around me during that time.”

It is notable that this same combination of the “Al-Aqsa Intifada” and the 9/11 massacre had a major impact in electrifying the Salafi Trend in Iraq that would later form the core of the Islamic State movement.

The independent Iraqi Salafis were greatly assisted by the official posture of Saddam Husayn, who was openly supporting the Palestinian suicide-killers and in early 2001 initiated a nationwide conscription effort for a new militia, Jaysh al-Quds (The Army of Jerusalem), which was supposedly going to go to the Holy Land and expel the Jews. The physical mobilisation of the population in tandem with the relentless State propaganda about Jaysh al-Quds, which by this point reflected the heavily Islamized nature of the regime, created something like a war hysteria in Iraq through 2001, where jihad was valorised, and Americans and Jews were defined as legitimate targets for violence. Many Iraqis were, therefore, primed to react to 9/11 with joy.

A savvier man than Saddam would have realised the danger he was in: that the risk calculus had just changed in Washington regarding the continuation of his regime, and that his strategic priority was reining-in the radicalism he had fostered and putting clear daylight between himself and Al-Qaeda. But that was not Saddam, who became the only ruler in the world to publicly welcome the 9/11 atrocities; even the Iranian mullahs and Colonel Qaddafi knew better than that. Late in the hour, Saddam still had a path to safety, but he “would not step out of harm’s way”.8

This recklessness was ubiquitous. Alongside trying to create a Salafi-infused religious current under his own leadership through the 1990s, Saddam had eased the repression of non-government Salafis, seeing them as a compliment to his program. One result was a process in which many Iraqis found they could take the Salafism without the Saddamism, even within the intelligence services and security forces. Senior officials begged Saddam around the turn of the millennium to change course and let them focus what resources there were on checking the Salafi Trend before it overwhelmed the State, but he refused, and, in doubling down on extremism after 9/11, the process accelerated.

The jihadist wing of the independent Salafis stepped up its da’wa (proselytism) in late 2001, and found a ready pool of recruits in Iraqis inflamed by an official discourse of jihadism, antisemitism, and anti-Americanism. Moreover, the jihadists could see that the Saddam regime was crumbling and turned seriously to preparing a unified military infrastructure that could hasten the advent of, and position the jihadists as the successor in, a post-Saddam era.

This was Iraq as it stood when the Islamic State’s founder, Ahmad al-Khalayleh, the Jordanian better-known as Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, arrived in Baghdad in May 2002. Iraq was not viewed contemporaneously as fertile ground for jihad, yet Zarqawi detected an opportunity. We can surmise what it was. Zarqawi saw what few outsiders could: the dual trendlines within Iraq, towards the implosion of the Saddam system and the rise of an increasingly powerful jihadist movement. The Anglo-American invasion in March 2003 brought forward the date where these two trendlines intersected, but that collision was in our future no matter what.

One of the first people Zarqawi met in Baghdad was Abd al-Rahman al-Qaduli (Abu Ali al-Anbari), a dominating ideological figure on the Iraqi jihadist scene and in time one of the IS movement’s most important figures. Al-Qaduli had worked to knit together the Salafi underground, and directed it towards a particularly virulent anti-Shi’a sectarianism and a devotion to ostentatiously extreme violence—strategic-theological elements shared with Zarqawi and opposed by Al-Qaeda, part of the fundamental incompatibility that tore asunder the contingent mid-2000s alliance of the Zarqawists and Al-Qaeda. Al-Qaduli was well-placed to bring large parts of the Iraqi Salafi infrastructure under Zarqawi’s charismatic leadership. Zarqawi then travelled unhindered around central Iraq, and toured Syria, picking up recruits like Taha Falaha (Abu Muhammad al-Adnani), the spokesman and global terrorism director of the caliphate era, and setting up the “ratlines” that would bring the foreign fighters and suicide bombers into Iraq after Saddam was gone. Zarqawi was back in Iraq by late 2002, and remained at liberty despite Jordan repeatedly messaging Baghdad with intelligence on Zarqawi’s whereabouts and requests for his arrest and extradition.

Al-Shara entered the fray on the eve of the invasion of Iraq, arriving in Baghdad “two to three weeks before the war started”, i.e. late February or early March 2003, to join the thousands of other foreign jihadists who had gathered to defend Saddam. By then, Al-Shara had “abandoned his university studies, grown a beard and traded his student attire for the austere robes of a devout Salafi.” Notwithstanding Saddam’s imposition of a form of shari’a domestically and his long record of collaborating with foreign Islamists, including Al-Qaeda, Saddam was a taghut (idolatrous ruler) by the letter of jihadi-Salafist doctrine and his demise was ordained of God. Al-Shara does not mention any cognitive dissonance on this point, but his mind might have been put at ease by the audio statement from Usama bin Laden, in early February 2003, explicitly calling for jihadists to fight for the Iraqi Ba’th regime, despite it being a socialist infidel system.

The aspect of this that Al-Shara is understandably silent about: he was sent into Iraq with the assistance of Bashar al-Asad’s regime, which he toppled in December. One wonders how much time Asad spends in his Moscow exile lamenting the irony of launching the career of the jihadist who destroyed him. When the decision was his to make, however, Asad always abetted jihadism: having permitted Zarqawi’s activities in Syria over the summer of 2002, Asad continued enabling the Iraqi jihad throughout the American regency, as both sides have confessed, and even when the IS networks “flipped” as the rebellion took hold in Syria in 2011, Asad staked his survival on empowering the jihadists within the insurgency.

AL-SHARA AND THE IRAQI JIHAD

Al-Shara has described his role in the Iraqi jihad this way:

I went to Baghdad. I stayed there. Then I went to Ramadi. At the time the war started, I was in Baghdad. Then after some time, I returned to Syria. Then I returned to Iraq again. Then I went to Mosul and spent most of my time there. Then I was arrested, and I was put in prison. I was put in Abu Ghraib prison. Then I was moved to Bucca then to Cropper prison, in Baghdad airport. The American forces then handed me to the Iraqis, who put me in al-Taji prison. I was released from al-Taji prison after spending a total of five years in prisons. … I didn’t meet Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. … I was a regular soldier. I wasn’t involved in any major operations that I would [require me to] meet al-Zarqawi. … I was in prison during the Shia-Sunni war that … started around 2006[.]

The evidence we have suggests that Al-Shara is telling the truth about this.

Within Asad’s secret police apparatus, it was the Palestine Branch (Far Falastin) or Branch 235 of military intelligence that handled the jihadists and other terrorist groups—maintaining lines of contact, infiltrating, and manipulating them. The Palestine Branch file on Al-Shara was inaccurate in numerous details about his life where the Branch had not directly gathered the information, but it recorded calling Al-Shara in for a meeting in Damascus on 10 November 2003 because of his “illegal” departure to Iraq, and “illegal” re-entry to Syria. Reading between the lines, the Palestine Branch was debriefing Al-Shara: trying to find out what he had done in Iraq, who he had mingled with, and any organisational affiliations he had made. Important for our purposes, it means Al-Shara did, as he claims, return to Syria after his first sojourn to Iraq, which must have lasted less than six months in 2003.

The leaks about Al-Shara in mid-April appeared on Sabereen News, an ostensibly Iraqi social media platform, which first appeared on Telegram in January 2020, days after Qassem Sulaymani was killed, and which has been since late 2020 “the most influential … social media channel” for spreading propaganda on behalf of Iran’s “resistance” (muqawama) forces, the Shi’a militias that are integral components of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC).

One package of the documents from Sabereen disclose that Al-Shara was arrested by the U.S. in Mosul on 14 May 2005, and Al-Shara successfully deceived his captors that he was an Iraqi from Mosul, born in 1980, named Amjad Muzafar Husayn Ali al-Nuaymi. Given prisoner number 174793, Al-Shara was held at Camp Bucca. Al-Shara was then handed over to the Iraqi government on 6 April 2010, and moved to Taji Prison. Al-Shara was released on 13 March 2011, two days before the conventional date for the beginning of the Syrian uprising. This all basically tallies with Al-Shara’s account.

The lack of mention in the documents of Abu Ghraib—officially the Baghdad Central Confinement Facility—is neither here nor there. The documents we have are not comprehensive, and in any case Abu Ghraib was a holding jail, where those arrested were processed before being sent on to the prison where they would serve their sentence.

There is a slight discrepancy in Al-Shara saying he was in prison for “a total of five years”, when the documents suggest it was nearer six, but one can understand how such a mistake can be made with Al-Shara speaking from memory more than a decade after his release. Moreover, if we had the complete records, it might be that Al-Shara spent some months at Abu Ghraib before serving a term that was more like five years at Bucca.

“Most of the information available [about me] on the internet is false”, Al-Shara said to PBS. A case in point: the reports that Al-Shara went to Lebanon in late 2006, after Zarqawi was killed, and helped out Jund al-Sham, cannot be true: Al-Shara was in prison. The specific context of Al-Shara’s remark was denying he had met Zarqawi. From the evidence we have, and what we know of IS’s security protocols, it is more likely than not that Al-Shara is telling the truth about this, too.

The outstanding discrepancy is the mention of Camp Cropper, a prison generally for high-value detainees, among them Saddam, who was held there until he went to the gallows in December 2006. Al-Shara was not of high-value when taken into custody in 2005. The leaked documents seem pretty solid that Al-Shara was never imprisoned there; he spent all his time at Camp Bucca. It is unclear why Al-Shara said he was held at Camp Cropper.

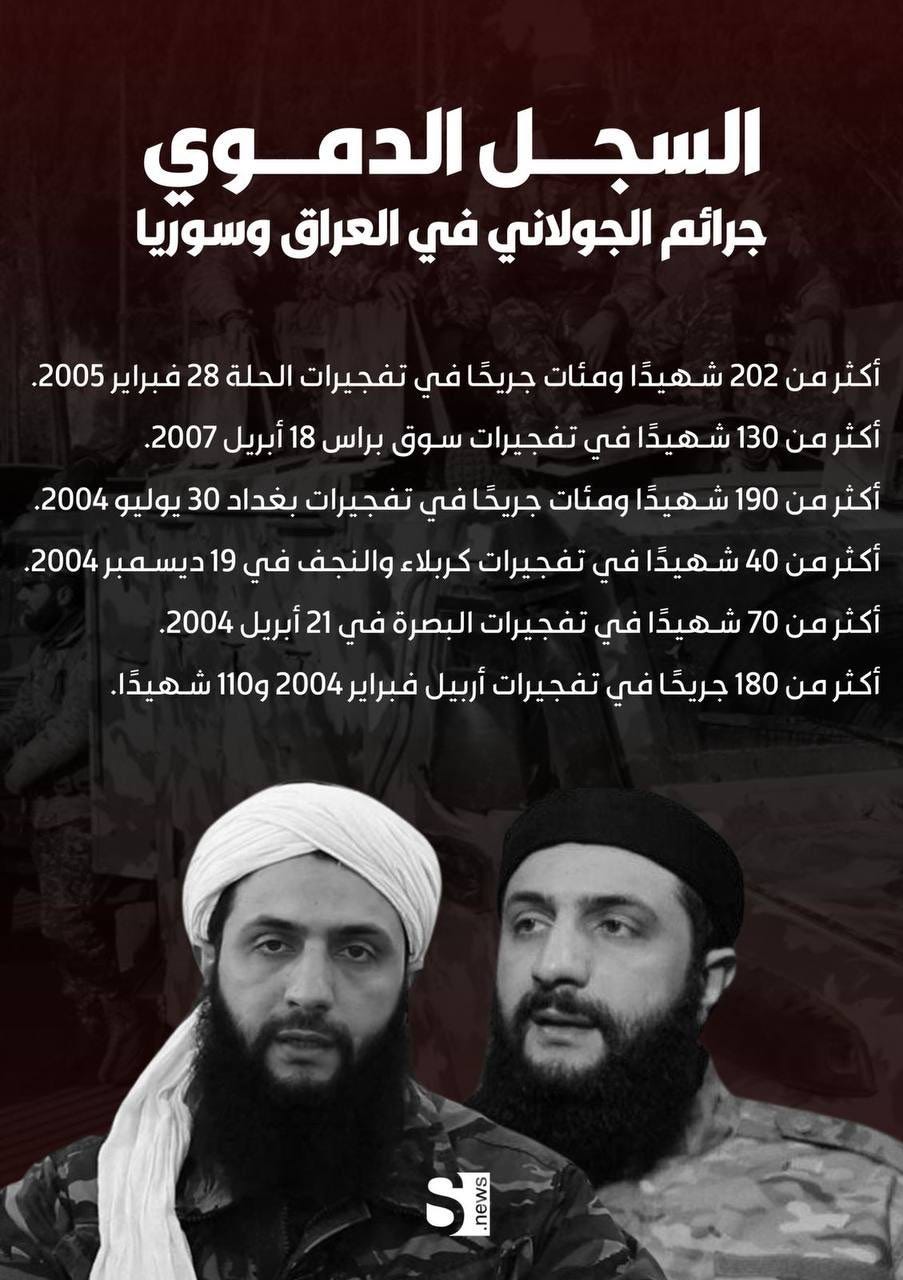

The crucial contemporary political dimension is that Iran has released these documents intending to buttress its claims that Al-Shara was personally involved in a litany of terrorist atrocities against Iraqi civilians, especially Shi’is. Sabereen has been circulating a poster with the title, “The Bloody Record: Al-Jolani’s Crimes in Iraq and Syria” (see below). “Al-Jolani”—fully, “Abu Muhammad al-Jolani”—is the kunya by which Al-Shara was best-known after 2011.

The charges laid against Al-Shara are:

Killing 202 people and wounding hundreds more in the Hillah bombings on 28 February 2005.

Killing more than 130 people in the market bombings across Baghdad on 18 April 2007.

Killing more than 190 people and wounding hundreds in the bombings in Baghdad on 30 July 2004.

Killing more than 40 people in the Karbala and Najaf bombings on 19 December 2004.

Killing more than 70 people in the Basra bombings on 21 April 2004.

Killing 110 people and wounding more than 180 in the Erbil bombings on 1 February 2004.

The second one, the marketplace attack, is false on its face: Al-Shara was in prison by then. The others are at least in a plausible time-frame, though we do not know when Al-Shara entered Iraq the second time, except that it was after November 2003. Clarity on that might rule Al-Shara out of personal involvement in some of the earlier atrocities listed for 2004. In the meantime, the Iranians have unintentionally exculpated Al-Shara from any accusations he was directly involved in Iraq’s sectarian civil war or IS’s operation to blow up the Askari Mosque in Samarra in February 2006 that started it.

Where the Iranian leaks backfired most spectacularly is in the document Sabereen leaked about Al-Shara’s release. Al-Shara had been held under the terrorism law (Article 4), it is explained, and “was released on 3/13/2011 due to there being no request for him from [i.e., he was not wanted by] any investigative authority and the lack of sufficient evidence against him”.

This is not dispositive: the list of dangerous jihadists the U.S. and Iraq held and then released because they never understood their biographies is depressingly long, and had baleful consequences in revitalising IS after the 2007-08 setbacks. But it does mean that on the current evidence—the evidence the Iranians themselves provided—Al-Shara is not the hands-on mass-murderer depicted in Iranian propaganda, and the balance of probability is that Al-Shara is not individually responsible for the specific crimes Sabereen charges him with. Moral and character judgments about Al-Shara for his past with IS—and views about his culpability in “international law” terms, if one goes in for that kind of thing—are rather separate, of course.9

THE JABHAT AL-NUSRA PROJECT

A lot had happened while Al-Shara was in prison from 2005 to 2011, most of it seemingly negative for IS: Zarqawi had been killed; the Zarqawists had ostensibly dissolved ties with Al-Qaeda and declared their State; the tribes and some insurgents had turned on IS and, with American support, dismantled the group’s territorial control and flushed IS out of many of its sanctuaries; Zarqawi’s successor, Hamid al-Zawi (Abu Umar al-Baghdadi), had been killed; the organisation virtually decapitated; and the new emir, Ibrahim al-Badri (Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi), was in deep hiding for security reasons.

Beneath the surface, however, the IS movement was into a recovery, as Al-Shara will have known, given the nature of the U.S. prisons. The worst of the Sahwa experience was behind them. Al-Zawi had done the hard work of reassessing the handling of the tribes, and set in place offensive operations that were gaining IS military and political momentum in Iraq, eroding and co-opting the Sahwa militias and positioning IS to capitalise on the impending American withdrawal, without the need for Al-Badri to do much. And right as Al-Shara emerged from prison, Syria was opening up before IS.

IS decided to hide its hand in Syria, given the negative coverage of its activities in Iraq over preceding years, and created a front group it called “Jabhat al-Nusra li-Ahl al-Sham” (The Support Front for the People of Syria), the advanced guard of which entered Syria in the summer of 2011 with Al-Shara at the helm.10 The first Al-Nusra attack in Syria, a twin suicide bombing outside buildings of Asad’s military intelligence agency in Damascus, took place on 23 December 2011, and Al-Nusra’s existence was formally announced on 24 January 2012. By the summer of 2012, Al-Nusra was taking a leading role in the Syrian insurgency, and by the end of the year its widespread popularity among anti-Asad populations was self-evident.

Explaining how Al-Nusra/IS established such a strong politico-military presence in Syria in 2011-12 is the easy part.

As mentioned, the Asad regime had hosted the IS movement on its territory for nearly a decade. Asad’s support for IS’s jihad in Iraq specifically involved enabling training camps in eastern Syria, where IS has the deepest roots in the country to this day, and facilitating travel between the east and the capital. We have direct evidence of IS leaders wounded in Iraq being transferred to Damascus hospitals and allowed to stay in the city afterwards as late as 2010. IS leaders were brought from the eastern sanctuary to Damascus so Asad’s secret police and the jihadists could jointly plan terrorist attacks in Iraq, and foreign fighters who arrived at Damascus International Airport were transported to the Mukhabarat-overseen IS bases in the east before they were sent over the border to ravage post-Saddam Iraq. In short, IS by 2011 was intimately familiar with traversing the Iraq-Syria border and the route from eastern Syria to Damascus: IS had operatives in place all along the way, and when IS transitioned from collaborating with Assad to fighting him, the switch could be flipped easily and effectively enough to allow strikes on fortified targets in Asad’s capital a short while later.

More intriguing is the evidence that IS was deploying some of its most senior and capable officials into Syria, in areas outside those tacitly agreed-upon by Asad, before the uprising began. In late 2010, IS’s overall deputy, Samir al-Khlifawi (Haji Bakr), was sent to Aleppo. Around the same time, another important IS military official, Adnan al-Suwaydawi (Abu Muhannad al-Suwaydawi or Haji Dawud), a colleague of Al-Khlifawi’s in the same air force intelligence unit during the Saddam days, was released from prison and went straight to the same area of Syria. We know very little of what this IS cell was doing in northwest Syria, but IS had always seen strategic potential in Syria’s geopolitical alignment and sectarian make-up and power structure. Perhaps, as with Zarqawi in Iraq in 2002, IS in 2010 intuited that in Syria the moment of opportunity was at hand.

The more seemingly puzzling question is: How did Al-Shara have the status to be appointed to lead the Nusra gambit? On paper, Al-Shara was an inexperienced young man when imprisoned and had only recently been released after more than half-a-decade off the battlefield. Why would IS trust him to oversee their operations in a whole new country?

Al-Shara gives the broad answer himself. “The prison played a part in the intellectual development of ISIS members, and what they’ve reached”, Al-Shara explained, adding that many of his fellow IS prisoners were “trying to turn the prison into an Islamic Emirate”, coercing inmates with “hideous measures” and even murder. Al-Shara disclaims any involvement in such things, saying his “methodology differed completely from that of others”. He rejected force, “largely”, in imposing Islam, and instead “tried as much as possible to spread the correct ideas. He continued this program to “educate people about the true concepts until I gained some popularity among the prisoners”.

Leaving aside whether Al-Shara was involved in intimidation and violence in prison, it is well-known that Camp Bucca was disastrously maladministered and functioned as an extension of the Islamic State: there were even cases of IS operatives deliberately getting themselves arrested to go into Bucca to take up positions within “the State” behind the wire—and not coincidentally to gain safety from the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), plus three meals per day at American taxpayers’ expense. IS’s bureaucracy ran as smoothly within the prison walls as outside them: the hierarchy was enforced, talent was identified, members were trained-up ideologically, slackers disciplined, and hard work and success rewarded with promotion. Al-Shara’s account alludes to his rise through the ranks in prison. The vagueness is perhaps borne of the mechanism by which this happened.

Al-Shara was imprisoned with Al-Qaduli, the ideologist Zarqawi met in Baghdad in May 2002 and who would have succeeded Zarqawi had he not been arrested in April 2006. IS had managed to conceal Al-Qaduli’s identity from the Americans, but the jihadists inmates knew who he was and Al-Shara became close to him, referring to Al-Qaduli in letters as “my beloved father”. Al-Qaduli certainly had powers of promotion and even by later IS accounts, after Al-Shara had “betrayed” IS in their perception, there is no effort to conceal that Al-Qaduli was impressed with Al-Shara.

The crucial general fact to understand is that IS operatives released from prison did not have to be re-vetted and reintegrated: IS detainees continued in their roles for “the State” in the prisons, and were not only kept abreast of developments outside the walls, but participated to some extent in the decision-making that brought these developments about. Just as Al-Shara will have known the course of IS’s jihad from 2005 to 2011 in real-time, the name Al-Shara made for himself in prison would have been known to IS’s leaders before he left prison, as would the backing he had from Al-Qaduli. This is why he was trusted for the Syria expedition.

The story Al-Shara tells of the specifics in putting the Nusra project together reflects this. Al-Shara says he won over another “important leader” in prison, and this man “got out of prison four months before me”, i.e., December 2010. This leader “was assigned the northern state [or northern province: wilayat al-shamal], which included Mosul and its outskirts”, one of the highest positions in IS at the time, a role that involved direct communication with Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

This “important leader” Al-Shara bonded with in prison was Fadel al-Hiyali (Abu Muslim al-Turkmani or Abu Mutaz al-Qurayshi), a close and old friend of Al-Qaduli’s. Al-Hiyali had been a senior official in Saddam’s security apparatus until Al-Qaduli converted him to jihadism. When Al-Qaduli began forming armed cells of jihadists in Iraq in early 2000s, he led the ideological training and Al-Hiyali was the military trainer. The duo had then joined Zarqawi straight after the regime came down and ascended the ranks side-by-side—doing their time in prison together, shaping the conditions for the caliphate declaration, and by the time of their deaths in 2015-16 Al-Hiyali was governor of Iraq and Al-Qaduli was governor of Syria. Only the caliph outranked them.

Back in the early months of 2011, according to Al-Shara, Al-Hiyali used the direct channel he had with Abu Bakr to prepare the ground for a plan he and Al-Shara had discussed in prison. Al-Shara says he met Al-Hiyali two days after his release and they wrote up the plan as a fifty-page proposal that was sent to Abu Bakr. Al-Shara then met in person with Abu Bakr and was given the go-ahead, as well as some money, supplies, weapons, and six men.11 Al-Shara slightly bemoans that this was some way short of the one-hundred he initially asked for, but he was somewhat misleading in saying, “I came with only six people”, as if IS had nobody else in Syria in the summer of 2011.

Post has been updated/corrected in the introduction. At the time of publication, Iraq’s government had pressed ahead with an official invitation to Al-Shara, despite the domestic furore. Subsequently, Al-Shara himself decided against the risks of making the trip.

NOTES

The sources for Husayn al-Shara’s biography are basically two: what his son said in 2021, and an account Husayn himself wrote as part of one of his books, which was written up by Al-Jumhuriya late last year. The fuller story is:

Husayn was born in 1946 in Fiq, a town in southern Syria near the border with Israel, where his father, Ali Muhammad al-Shara, owned most of the land. In his teens, Husayn reacted against this elite upbringing and was caught on the wave of Arab nationalism. Thrilled by Egypt’s ruler, Gamal Abdel Nasser, the icon of pan-Arabism, Husayn supported the “union” of Egypt and Syria in 1958 in the so-called United Arab Republic (UAR). The UAR amounted to an Egyptian occupation of Syria, but Husayn did not see it that way: he welcomed the imposition of nationalist socialism and protested against the military coup in Damascus in September 1961 that liquidated the UAR. Husayn also opposed the takeover of Syria by the Ba’th Party in 1963 and was imprisoned for four days. The Ba’thists were forced to release Husayn by popular protests, and he fled the country to Jordan. Intending to travel on to Cairo, the political situation in Amman was prohibitive, so Husayn went to Iraq, where a radical republic on the Nasserist model had come to power in a sanguinary revolution.

Husayn was ostensibly a student in Iraq, studying engineering, but in his spare time he took up with the fedayeen of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) after it was created in 1964 and had an unspecified role in its terrorism campaign against Israel. The defeat of the second Arab attempt to destroy Israel in 1967 had consequences beyond the ideological for Husayn: his father was displaced in the fighting, and was unable to return home afterwards because the war finished with Israel holding the Golan Heights and the Arabs refused to negotiate the peace that would have secured its return. Husayn’s opposition to Ba’thism at home did not apply in Iraq: the Ba’th seized Baghdad in 1968 and Husayn stayed on without issue to complete his studies, returning to Syria in 1969. Perhaps demoralised by the Six-Day War, Husayn does not seem to have continued his association with the PLO, by now run by Yasser Arafat, thus was not involved in the “Black September” episode in 1970, when the PLO’s coup attempt in Jordan was thrown back and then the group was thrown out—decamping to Lebanon, where the PLO had started another civil war within half-a-decade.

After spending a year as an English teacher in Deraa, Husayn was on good enough terms with the Syrian Ba’th regime—newly headed by Hafez al-Asad—to be given a job in the State oil industry, studying the economics of the sector and training civil servants. He was not, however, on good enough terms to be allowed to take a seat on the Qunaytra local council in the 1973 “elections”. In the aftermath of the Arabs’ third failed war to eliminate Israel, amid the discovery that oil could be used as a political weapon, Husayn published his first book, Oil Between Imperialism and Development, and a second book a few years later, Petroleum and Arab Money in the Battle of Liberation and Development.

Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin (2005), The World Was Going Our Way: The KGB and the Battle for the Third World, pp. 386-419.

Thomas Hegghammer (2020), The Caravan: Abdallah Azzam and the Rise of Global Jihad, pp. 107-10.

Stéphane Lacroix (2011), Awakening Islam: The Politics of Religious Dissent in Contemporary Saudi Arabia, pp. 51-52.

Hassan Hassan (2016, June 13), ‘The Sectarianism of the Islamic State: Ideological Roots and Political Context’, Carnegie Endowment. Available here.

In a 2018 interview with The Washington Post, Saudi Arabia’s current de facto ruler, Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman, made reference to “[Saudi] investments in [spreading Wahhabism in] mosques and madrassas overseas [being] rooted in the Cold War, when allies asked Saudi Arabia to use its resources to prevent inroads in Muslim countries by the Soviet Union.” There are obvious reasons to be cautious with the testimony of MBS, but in this case there is a wealth of independent evidence to support what he says.

Husayn al-Shara was a columnist from 1980 to 1986 at Al-Riyadh, the “semi-official” newspaper of the Saudi Court, and from 1986 to 1988 at Al-Jazirah, where there was a little more flexibility.

Fouad Ajami (2006), The Foreigner’s Gift: The Americans, the Arabs, and the Iraqis in Iraq, p. 54.

As late as December 2002, a year and more after 9/11, Saddam was being given one final chance to comply with the United Nations disarmament program. The consequences for defiance were plain for all to see: an enormous American-led force was amassing on his border, and this time, unlike 1991, it had been plainly stated that if hostilities began those troops were coming to Baghdad to make an end of Saddam. In the event, Saddam not only rejected the chance to save himself by handing over duplicate and false documents, on the day he handed over the documents he issued a public statement calling for a common front of “jihad” with “the mujahideen” against the Americans, the British, and the Jews.

If one believes in “international law”, it is possible to argue Al-Shara is guilty of everything IS did while he was a member, thus between about 2003 and 2013, since he had entered into the organisation’s “common plan”. This “joint criminal enterprise” (JCE) doctrine, innovated at Nuremberg and derived from America’s “conspiracy” laws used to fight organised crime, is dubious in the extreme and was controversial from the beginning. The French, for instance, opposed it root-and-branch. The most high-profile recent application of the JCE paradigm was Bosnia, and it produced a number of scandalous decisions.

Morally, the central fact is Al-Shara did join the Zarqawists and his explanation that this was the follies of youth is unconvincing. Al-Shara was 20-21 when he first went to Iraq. From 2003 to 2005, IS had, inter alia, already begun the video beheadings, shot down female members of the provisional government, levelled the offices of the United Nations and the Red Cross, massacred Shi’a pilgrims on their holy days, and slaughtered Iraqis who tried to participate in the democratic process. Al-Shara was 20-23 in this period, was in Iraq for some of it, and returned to Iraq and stayed in the field fighting for IS through it all. Al-Shara was part of “the State” behind the wire from 2005 to 2011 and went straight back to work when he got out of prison thereafter, now aged about 29, which adds a caveat to his non-involvement in the 2006-08 sectarian civil war; at a minimum, IS igniting that war and mercilessly prosecuting it was not a dealbreaker for Al-Shara, and how could it be? Such strife was the core of Zarqawi’s strategy in Iraq, as everyone had known since early 2004.

Al-Shara’s break with IS in 2013 had an ideological dimension, but Al-Shara’s personal status and power were rather more salient as proximate causes. That Al-Shara broke with IS to join Al-Qaeda qualifies any credit he is to be awarded, even if he did later seemingly wriggle out of his obligations to Al-Qaeda, too.

It has been reported many times that Al-Nusra’s advanced guard went into Syria in August 2011, though a captured senior IS operative said it was July 2011.

The story of Al-Nusra entering Syria with a seven-man advanced guard has been known for some time. Of the six men with Al-Shara, one, an important Iraqi veteran of IS, is well-known to have been Maysar al-Jabouri (Abu Mariya al-Qahtani), and another was Iyad al-Tubaysi (Abu Julaybib), a Jordanian-Palestinian and brother-in-law of Zarqawi’s. The other four were reportedly Bassam Ahmad al-Hasri (Abu Umar al-Filistini), a Palestinian IS operative who had been imprisoned in Sednaya until Asad turned him loose with hundreds of other jihadists in the spring of 2011; Mustafa Abd al-Latif al-Saleh (Abu Anas al-Sahaba), a Jordanian-Palestinian with extensive experience in Syria working as an IS facilitator and foreign fighter recruiter; and two Syrians, Anas Hassan Khattab, another regional facilitator, and Saleh al-Hamawi.