The Petrov Affair: Australia’s Most Sensational Spy Case

Australians had no idea on 3 April 1954, seventy years ago last Wednesday, that a senior Soviet intelligence officer based at the Canberra Embassy had defected, and nobody had any way of knowing that the Soviet reaction was about to create one of the most dramatic stand-offs in the early Cold War. Even less predictable was the internal reaction by the Left-wing Labor Party, specifically its leader, which was to transform the defection into the most sensational and politically consequential spy incident in Australia’s history, remembered as the “Petrov Affair”.

FROM WORLD WAR TO COLD WAR

The Soviets and their Nazi allies had started the global conflagration in 1939, and inevitably turned on one another in 1941. The United States and Britain had taken the decision to rescue the Soviets from the consequences of their embrace of Hitler. The Australian Commonwealth, formed as a federation of the six British colonies on the continent in 1901 and refashioned as a self-governing Dominion in 1907, had obtained legislative independence in 1931, but remained an integral part of the British Empire at the outbreak of war.

Australia’s Second World War was truly global. A million Australians fought with the British Empire, some even flying planes to defend Britain during the darkest moment of the war, in August-September 1940, when Hitler had virtually completed his conquest of Europe and was trying to terrorise Britain into surrender via “the Blitz”. Australians endured defeat with the Allies in Greece in 1941 and played an important part in the success at El Alamein in 1942. Australia was involved in dislodging the Nazis from the Middle East.

Australia was significantly diverted to the Pacific theatre after the entry of Japan into the war in December 1941 and the fall of Singapore in February 1942, not least because the latter was so swiftly followed by air attacks on Darwin, the first attack on the Australian homeland in its independent history, the first of more than 100 Japanese air raids on Australia in 1942-43. Shortly after that, Japanese submarines appeared in Sydney Harbour. Australia became the staging ground for, and a major participant (along with New Zealand) in, the U.S.-led campaign to drive Japan from its conquests. A third of the 21,000 Australians captured by the Japanese perished. Australians were still fighting in Borneo when the atomic bombs broke Japan’s will.

Despite the Pacific War on her doorstep, Australia did not leave the European theatre after 1941. At great cost in lives, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) played an important combat role on D-Day, and supported various anti-Nazi resistance forces, such as the Jugoslav guerrillas and the Poles during the Warsaw Uprising. The RAAF’s provision of supplies to Warsaw in 1944—while the Red Army hung back to let the Nazis ravage the city—led to considerable admiration for Australia among Poles, and a large number of Poles who could not live under Communism moved to Australia at the war’s end, an important part of the background that created the setting for the Petrov Affair.

The Cold War is often dated to Winston Churchill’s speech in Fulton, Missouri, in March 1946. In truth, the Cold War began with the Bolshevik coup in November 1917. Vladimir Lenin had seized control of Russia with no concern for the country itself, merely the intention to use it as a launchpad for worldwide Communist Revolution, and he set about implementing this program in Europe immediately, pausing only when checked by force of arms. Russia became the Soviet Union and under Lenin’s chosen successor, Joseph Stalin, was transformed into the nerve-centre of a global apparatus of subversion.

Britain and America had continued to supply Stalin’s Red Army even after the existential crisis of 1941 had passed, empowering it to rape and massacre its way across half of Europe. What the Anglosphere envisioned as a “Grand Alliance” was seen by the Soviets as a monumental opportunity to bring down the “capitalist imperialists” from within, an opportunity exploited to the fullest, with the American government vastly infiltrated by Soviet spies and the British intelligence system turned inside out. When Churchill spoke, it was against the background of East-West political warfare at the Nuremberg Tribunal to finish with the Nazi war criminals, and the struggle to get Soviet troops out of Iran. The West would prevail in Iran, and in Greece the next year; these were the exceptions. China and North Korea fell to the Soviets, leaving a third of the surface of the planet—the bulk of the Eurasian landmass from the Fulda Gap to Peking—under Communist rule in 1945, with ongoing attempts to expand Soviet control into Western Europe and a resort to overt military aggression to try to expand in Asia.

It was in this crisis situation that the United States initiated a dual-track policy in 1947 of loyalty-security programs to comb the Soviet agents out of the State, and effectively a public education program to hinder the work of the Soviet intelligence services by inculcating an understanding of Communism’s methods and intentions in the American population, which was modelled significantly on the suite of policies (and laws) that neutralised the Axis fifth column during the war. The anti-Communist program was more difficult because it was having to undo the wartime propaganda about the friendly “Uncle Joe” and it competed with an elite intellectual climate much more sympathetic to Communism than it ever had been to Nazism. This latter problem is a crucial reason why the anti-Communist crackdowns after the two world wars are remembered as “Red Scares”, while the term “Brown Scare” did not stick in relation to President Franklin Roosevelt’s far more aggressive and legally dubious anti-Axis crackdown.

Telling the story of the early Cold War controversies over Soviet espionage—how much of a danger it was, whether the State was overreacting, the alleged misuse of national security threats for political purposes—as an American story summed up in the word “McCarthyism” is to misunderstand reality, though. For one thing, the first Western country to wake up to the internal Communist threat was Canada, after the 5 September 1945 defection of Igor Gouzenko, a cypher clerk for the GRU (Soviet military intelligence) at the Ottawa Embassy. Gouzenko’s revelations, aired at a high-profile Royal Commission beginning in February 1946, set out in considerable detail the methods and extent of Soviet espionage, and led to the prosecution of numerous Soviet agents.1 The process recurred throughout the West, as States—many of them fresh from totalitarian occupation and still trying to sweep rubble off the streets—sought to find stability and security in a new world, where Communism was on the march after the Soviet victory in the Second World War. The Petrov Affair was part of how this process worked itself out in Australia.

THE COLD WAR DOWN UNDER

At the outbreak of war in 1939, the Australian Prime Minister was Robert Menzies, then-leader of the conservative United Australia Party (UAP), who threw the country wholeheartedly into the anti-Nazi struggle. The Australian Labor Party (ALP) managed to form a minority government in October 1941 under Prime Minister John Curtin, an intriguing wartime leader under the British Imperial banner given his origins on the Marxist Left. Such an ideological background might well have been among the factors that made it so easy for Curtin to turn to America in December 1941, “free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom.” Curtin won a landslide victory in the Federal Election of 1943 and then died in July 1945, to be replaced by Ben Chifley, a figure of Clement Attlee-like stature in Australia, who won the 1946 election with a slightly reduced majority. In December 1949, with socialism working no better in Australia than it has anywhere else, the landslide went against Labor, bringing Menzies back to office at the head of a coalition consisting of the Liberal Party (Australia’s Tories), which he had founded in 1945 to succeed the UAP, and the older National Party (originally Country Party), an agrarian conservative outfit. Menzies was to become Australia’s longest-serving Prime Minister.2

There was a material discontent because of the inflation caused by Chifley’s policies, and Chifley trying to nationalise the banks played into an ideological theme of Menzies’ appeal, namely anti-Communism. Western populations in the late 1940s and early 1950s, especially the middle classes, were spooked by what had happened in Eastern Europe, and they wanted answers about how to prevent it happening to them.

The political debate roughly divided between the Left’s contention that Communism was a perversion of the ideals of social justice whose success could be attributed to it feeding on, as we would now say in “extremism” discourse, “grievances”—lack of economic opportunity, colonialism, ethnic discrimination, whatever—and the Right’s argument that Communism was an international movement with its headquarters in Moscow that existed as a logical culmination of liberalism or progressivism.3 Menzies was able to make this case against Chifley: that whatever his subjective intentions, he was objectively taking Australia down the road to serfdom, and his party was riddled with fellow travellers. Whatever one makes of the broader argument, on this latter point Menzies was able to exploit an unarguable fact—visible to all and originating before the Bolshevik coup—which bedevilled the Left all through the Cold War: an inability to create internal firewalls against Communists.4 As we shall see, this problem was even worse in the Labor Party than it appeared.

The argument over where Communism came from was also an argument about how to handle it. For the Left, the solution lay in ameliorating the grievances so that people were not attracted to the misguided answer Communism offered. For the Right, such a course was of marginal importance, since Communism did not arise as an internal phenomenon with mass support, but was imposed from outside by minorities—often through outright force. The solution for the Right, therefore lay, as it had with Nazism, in a fulsome ideological assault on Communism and energetic resistance to its aggression, militarily where necessary and through stringent security measures to neutralise its agents.

These had been the contours of the debate leading into the 1949 election, where Menzies ran on a platform of banning the Australian Communist Party (ACP). The Right’s perspective had gained traction in this period because of a violent coal strike, where the scale of Communist influence—out of all proportion to their small numbers—had become so evident. It was an influence recognised by Chifley himself, who invoked it as justification for using the Army to break up the strike.

Labor eventually let the bill banning the ACP pass in late 1950—Labor had a narrow majority in the Senate—but the hesitancy of the party and the courts striking down the law in March 1951 played into Menzies’ hands in the April 1951 Federal Election, as did the Soviet attempt to conquer South Korea in June 1950, which required the deployment of Australian troops under the United Nations flag to prevent Stalin rounding out his victory in Asia, another vindication, as far as most Australians were concerned, of the Right’s argument that the Communist problem was rooted in armed minorities controlled from Moscow trying to impose their will on free peoples.

Menzies was able to argue in the 1951 election that with judicial activists more concerned about Communists’ civil liberties than national security and the Opposition at best unserious in confronting the Communist menace, only the Liberal-National Coalition (LNC) could be trusted to protect Australia. The public agreed: the LNC’s majority in the House of Representatives was reduced by five seats, but the LNC gained a six-seat majority in the Senate. After the election, in September 1951, Menzies held a referendum on changing the constitution to allow the banning of the Communist Party, which was defeated by the narrowest margin, with 50.56% against.

A side-note: Australia’s attempt to ban the Communist Party occurred several years before the legal prohibition of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) under the 1954 Communist Control Act. True, the U.S. had de facto outlawed the CPUSA in 1949-50 under the Smith Act that prohibited advocating the overthrow of the government. Still, it was part of a trend that became more pronounced as the twentieth century went on, where political ideas and themes innovated in Australia would be taken up in Britain and the United States.5

In March 1953, as a two-year Soviet antisemitic campaign was cresting, with signs of something truly horrifying in the offing, Stalin was struck down by a stroke—on Purim, as it happened. A few days later, Stalin died, and a power-struggle erupted in the Soviet Union. Stalin’s murderous, sexually predatory secret police chief, Lavrentiy Beria, was outpointed in a coup in June 1953—and put to death for treason in December 1953. One effect of the internal Soviet turmoil, in combination with Dwight Eisenhower becoming U.S. President in January 1953 and taking a more overt hard line with the Soviets, was the implementation of an armistice in Korea in late July 1953. Another effect was creating a measure of chaos within Soviet intelligence, which was to provide part of the context for the showdown over Soviet espionage Down Under.

THE EARLY CAREER OF VLADIMIR PETROV

In The Petrov Affair: Politics and Espionage, Robert Manne gives an account of the career of Vladimir Petrov, and the road to his defection in Australia in 1954.

Petrov joined Soviet intelligence in 1933 and worked as a cypher clerk, transmitting messages between the various stations of the NKVD (the KGB’s predecessor) in Stalin’s Empire. Huge numbers of NKVD officers were killed in Yezhovshchina (the Great Terror), but at its height, in September 1937, Petrov was promoted. After a spell in Urumqi, the provincial capital of Xinjiang in China, where an anti-Soviet rebellion was savagely crushed, Petrov was called back to Moscow in February 1938 to direct cypher traffic between Moscow Centre and NKVD units within the Soviet Union, mostly consisting of transmitting and receiving confirmation of the death lists to meet Stalin’s quotas. In this role, Petrov was a witness—and firm believer in the charges—at the last of the major show trials, the “Trial of the Twenty-One” in March 1938, which was Stalin’s means of disposing of, among others, Nikolai Bukharin, the leader of the Right Opposition, and Genrikh Yagoda, the NKVD chief who had set Yezhovshchina rolling, only for it to quickly consume him.6 As the worst of Yezhovshchina wound down, Petrov was moved into cypher work coordinating among the functionaries who oversaw the GULAG concentration camps and their slave labour inhabitants.

Petrov’s other half, Evdokia Kartseva, had to this point had a more impressive career than his and was certainly more valuable to Western counter-intelligence—she had served in one of the specialist cryptanalysis (code-breaking) sections of the NKVD, focused on Japan—but she had also had a very close brush with Yezhovshchina. In 1936, Kartseva had entered into a relationship with a man in her section Roman Krivosh, a man of Balkan origins who had been a cryptanalyst for the Okhranka, the Tsar’s political police, as had his father. This noble lineage and foreign origin meant Krivosh was on borrowed time. In 1937, months after the couple’s daughter was born, Krivosh was duly dispatched to a GULAG. Kartseva denied all knowledge of her husband’s imaginary treason; she was convicted anyway, but the verdict was overturned it seems after the intervention of someone high-up in the NKVD. Shortly before the tragic death of Kartseva’s young daughter in 1940, she married Petrov—a marriage of pure convenience, in best NKVD tradition. Petrov was attracted to Kartseva and unconcerned by the “blemish” on her record; she was looking for the security of a relationship with someone in good standing with the Party.

The Petrovs remained at their posts with the skeletal NKVD cypher staff during the Nazi siege of Moscow in 1941, and were rewarded with an overseas posting as Legals in the Embassy of neutral Sweden: “Here Petrov combined control of cyphers for State Security with … surveillance of Soviet citizens abroad. … He was also involved in a special investigation into the loyalty of the Soviet Ambassador to Sweden—the grand old lady of the October Revolution—Alexandra Kollontai. … Evdokia Petrova, freed from her specialist cryptanalytic work, blossomed in Stockholm into an all-purpose intelligence officer, working as State Security typist, accountant, cypher clerk and photographer, and even running two female Swedish agents in the field.”

The couple returned to Moscow in October 1947 and took up desk jobs with what was by then the Committee of Information (KI), an ill-fated attempt to combine foreign and domestic intelligence.

THE PETROVS ARRIVE IN AUSTRALIA

After three years back in Moscow, the Petrovs took up their second (and final, as it transpired) foreign posting at the Soviet Embassy in Australia in February 1951. One of the people to meet the Petrovs and get them settled was a TASS “journalist”, Victor Antonov. Soviet media outlets were always staffed by a significant number of intelligence officers, and the Soviets never lacked for agents at Western newspapers, either—a fact that was to become highly salient later on.

What the Petrovs quickly discovered was disarray in the Residency (intelligence station within the Embassy), with various sexual shenanigans and embezzlement. Several staff were recalled to Moscow, leading to Vladimir’s de facto promotion as he took over various responsibilities. In April 1951, Vladimir official became Third Secretary, with nominal cultural and consular duties that required frequent travel to Sydney and Melbourne, providing cover for his real job of surveilling the newly-arrived refugees in Australia from areas conquered by the Red Army, above all Poland and the Baltics, and cultivating, recruiting, and meeting agents from among them. The Soviets had proven adept at infiltrating anti-Communist émigré organisations since the Revolution took over Russia, beginning with the operations in the 1920s and 1930s to take apart the remnants of the Volunteer Army (“Whites”) that had fought to resist the Bolshevization of their country in the civil war. Petrov’s mission was in this tradition.

Evdokia had been charged with providing “clerical, cypher, and operational assistance” to the Residency. The staff shortage derailed Evdokia into filling in as typist and bookkeeper, including for the Soviet Ambassador, leaving little time for intelligence work.

On a trip to Sydney in July 1951, Petrov discovered a Polish Jewish doctor, Michael Bialoguski, who had been arrested in 1939 when the Soviets swept into Vilnius—then a heavily-Jewish Polish city, now the capital of Lithuania—and managed to escape to Australia in 1941. As Bialoguski was a Pole and was working with many Baltic refugees, he seemed a promising contact for Petrov. The KI experiment was terminated in December 1951 and Vladimir became acting rezident (“station chief”, in American parlance), promoted to a full colonel in the MGB, as it then-was (it became the KGB in March 1954). By this time, Petrov believed he had recruited Bialoguski, giving him the codename GRIGORII.

The problem was that Bialoguski was already an agent for Australia’s intelligence services, under the name DIABOLO, and had been for six years, being passed to the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO), the counterpart to MI5 and the FBI, when it was created in March 1949 on the initiative of Chifley. Menzies would establish the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS), the equivalent of SIS/MI6 and the CIA, in 1952. It is important to emphasise that Australian intelligence was not—and is not—nationally isolated. During the Second World War, Britain and her daughters—Australia, Canada, and New Zealand—had forged with the United States a shared intelligence system that was continued after the war and officially institutionalised in the UKUSA Agreement, not coincidentally signed in March 1946. This Five Eyes system, the backbone of which is signals intelligence (SIGINT), with collection tasks divided between members and the products shared, is unique in intelligence history: a cooperative information-sharing mechanism among States that (very nearly) do not spy on each another. Five Eyes was the highest priority target of the KGB throughout the Cold War, and one of the worst compromises would occur in Australia in the 1970s, though it was not discovered until after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Bialoguski, a physician with a line in illegal abortions, a skilled violinist, and an inveterate womaniser, had worked to infiltrate Communist front organisations for ASIO, becoming a member of the executive committee of the New South Wales Peace Council and a prominent member of the Russian Social Club, where he first met Petrov. Bialoguski spied on Petrov in the early stages through a young Russian woman, Lydia Mokras, a nurse on the Eastern Front until she was taken captive by the Germans. The experience does not seem to have done anything to help Mokras’ mental stability. Among Mokras’ strange behaviour was rather loudly hinting at gatherings that she was a Soviet spy—something she admitted was untrue in debriefings with ASIO later. But Mokras was Petrov’s mistress, and soon Bialoguski’s, able to confirm for ASIO that Petrov was a “big shot” at the Residency, even if much of the rest of her information was useless.

Mokras aroused Petrov’s suspicion when he checked with the Centre and discovered she was not a Soviet agent. Petrov asked Bialoguski to spy on her, ironically. ASIO’s patience was also exhausted with Mokras—they told Bialoguski to drop her—and it made ASIO suspicious of Bialoguski ever-afterwards. At best, he had shown poor character judgment; at worst, he was a Soviet plant and was working with Petrov to draw Australia into some embarrassing debacle. ASIO counter-intelligence took over handling Bialoguski and in March 1952 even arranged for a spy, another Pole, to surveil their own agent. The problem with assessing Bialoguski’s ultimate loyalty was that all the “suspicious” things he did—building a closer relationship with Petrov and attending meetings at Communist fronts—were what ASIO needed him to do.

Bialoguski and Petrov spent a lot of time together from 1952 onwards, but any blurring of social and professional boundaries was mostly on Petrov’s side, where the need to cultivate his “source” was used to disguise to the Residency his use of official money to enjoy the nightlife (and women) of Sydney. Petrov seems to have barely gone through the motions of cultivating Bialoguski,7 while Bialoguski, who no doubt enjoyed these outings, never lost sight of his job, taking advantage of Petrov’s perennial over-drinking to find out about goings-on at the Embassy, including the distrust of Petrov’s superiors, displayed most obviously by his driver reporting on him. As early as February 1952 Bialoguski identified Petrov as a potential defector, or “Cabin candidate” in ASIO code. In May 1952, Petrov began staying over at Bialoguski’s flat in Sydney, usually passing out drunk, allowing Bialoguski to rifle his pockets for business cards, names and addresses written on scraps of paper, and anything else, all fully reported to ASIO. (On one—perhaps the one—occasion where Petrov was not blackout drunk, Bialoguski slipped him a sleeping pill so he could search his pockets.) None of it eroded ASIO’s suspicion of Bialoguski, however.

It was around this time Bialoguski came to realise ASIO’s distrust of him, accusing them (probably correctly) of bugging his telephone and searching his flat in his absence. Bialoguski’s request for an increase in payment—a persistent theme of his ASIO tenure—this time for the flat, which he said had already proven in its value, was refused, and he theatrically wrote a letter of resignation he clearly hoped would be turned down. When it initially was not, Bialoguski offered his services to the CIA. Bialoguski’s contact was reported to ASIO, and he was ultimately brought back in.

The Centre had criticised the Australian Residency generally in mid-1952 and reprimanded Petrov personally in early 1953, just before Stalin’s death. In April 1953, Petrov was recalled, set to return to Moscow in late May, but an eye operation kept him in Australia. ASIO finally gave Bialoguski the go-ahead to make an approach to Petrov about defecting, something Bialoguski had been pushing them to do for months—but Bialoguski was only permitted to do it in the indirect manner he had told ASIO would not work. The circuitous attempt to induce Petrov’s defection while he was in a Canberra hospital bed, with Bialoguski sticking to the ASIO script of, for example, highlighting the superiority of Australian healthcare, trying to get Petrov to come to the realisation by himself, was a dismal failure.

ASIO’S FIRST DIRECT APPROACH TO PETROV

Beria’s downfall, the news of which reached Australia on 10 July 1953, caused ASIO to change its mind about a direct approach to Petrov. Petrov’s delayed flight to the Soviet Union was cancelled altogether and the turmoil being reported at multiple Residencies in the West convinced ASIO this was the moment to make a move—without Bialoguski. Still doubting Bialoguski’s reliability, and regarding him as a “mercenary” who was over-eager and insensitive to diplomatic concerns, ASIO would make its own direct approach to Petrov. “The man ASIO selected to make the approach to Petrov was Bialoguski's Macquarie Street neighbour and Petrov’s eye doctor, H.C. Beckett”, writes Manne.

When Petrov went for his (needless, ASIO-arranged) eye check-up with Beckett on 23 July, Beckett said that returning to the Soviet Union “with all the changes taking place” after Beria’s removal seemed like a grim prospect: Australia was so much nicer, and he knew the “right people” who could help Petrov stay and maintain his status and income. Petrov did not react, remaining “poker-faced”, as Beckett later testified, but Petrov had got the message, and when he got into the car outside with Bialoguski the first thing Petrov said was that Bialoguski should be careful since Beckett “has some connection with the Security people”. Bialoguski quietly seethed at the pointed snub that had taken place, but dutifully reported everything to his handlers—only for some at ASIO to blame Bialoguski for telling Petrov of Beckett’s Security connection.

Petrov was furious at what had happened with Beckett, as he would remain for the rest of his life. Mostly Petrov was embarrassed. The encounter came atop the Centre’s criticism, and the taunts from colleagues at the Embassy, fuelling Petrov’s self-doubt about his abilities for “proper” intelligence work, most of his prior service having been desk-work. When Petrov returned to Beckett’s surgery for another pointless check-up the doctor had arranged on 22 August, Petrov loudly and insistently praised the Soviet Union when any comparison with Australia was brought up, decisively shutting down any attempt to turn him.

In September 1953, as it seemed Petrov’s defection was a “dead duck”, Bialoguski put in yet another request for increased pay and when it was refused, he blew up, as he had four months earlier, only this time he sought to take the matter directly to Prime Minister Menzies. That did not happen, but Bialoguski did have two meetings in Canberra with Geoffrey Yeend, Menzies’ Private Secretary. The exact content of these meetings is disputed, but the upshot was that ASIO told Bialoguski his service with them was at an end. Given the conspiracy theories that Menzies timed the announcement of Petrov’s defection for electoral purposes, Manne emphatically underlines that Menzies did not meet Bialoguski, did not even try to take any kind of control over the Petrov operation, and the outcome of these meetings was the dismissal of “the only man who could genuinely advance the cause of the Petrov defection”, an odd first move if one was planning to use Petrov’s defection to sway an election that was only eight months away.

Later, Petrov would claim his misery in the months after Beria’s fall was intense. As well as wallowing in his own sense of inadequacy, Petrov said his already poor relations with the rest of the Embassy staff—the Ambassador’s team, more than the Residency—neared breaking point. Part of this was because of his wife. Evdokia could be “sharp-tongued” with colleagues, in her telling mostly about their petty corruption, including that of Ambassador Nikolai Lifanov, and some of the malicious gossip about Evdokia was quite dangerous, such as “that she had placed a photograph of a film star in too close proximity to the portrait of Stalin on her desk”. Even more dangerous, Petrov said that he and his wife were falsely reported to the Centre for trying to form an anti-Party, pro-Beria faction at the Embassy.

As Manne documents, there is something not quite right in this picture. For one thing, Lifanov had been recalled in July 1953 and Petrov was optimistic about a fresh start with the new Ambassador, Nikolai Generalov. Likewise, the Beria angle to the story of Petrovs’ declining relations at the Embassy does not add up. Such an accusation at that moment would probably have been lethal, definitely so if made multiple times. Yet the summer-autumn 1953 period was when the Petrovs began, in collaboration with Bialoguski, a series of money-making schemes, some of them illegal under Australian law, never mind Soviet regulations.8 It is not the kind of risky behaviour one expects of people living in fear for their lives. These schemes also “complicate” Evdokia’s narrative that she incurred her colleagues’ wrath by being an oasis of probity in a desert of corruption.

The targeted hostility of Ambassador Lifanov towards the Petrovs seems real enough, and at least some of it was because Evdokia rejected his advances, the root of the problem with several other male colleagues. Evdokia’s blunt criticism of colleagues’ incompetence and corruption (however hypocritical the latter was) undoubtedly played a part, and there was some “honest” suspicion—not only from Lifanov—about her Western dress-senses and tastes in music and film. Lifanov certainly had a personal grudge against State Security, too, which he took out on both Petrovs.9 This was not the whole story, though. Some of Evdokia’s outbursts were needless and rude by any definition, and Petrov was not only less bureaucratically diligent than he might have been, creating strains on the Ambassadorial relationship, but a series of drunken escapades would have caused problems for Petrov no matter who was Ambassador.10

The obvious advantage for the Petrovs of the notion that they fell from grace because of accusations they were pro-Beria is that it makes it a story about the frightening ideological lunacy of the Soviet government, and deflects attention from any unseemly details about the Petrovs that might have contributed to the rupture. A further data point in assessing this account—told most insistently by Evdokia—is that it got more concrete over time, which is always a red flag. Another evidence-against-interest consideration is that this story meshed very well with ASIO’s political-bureaucratic needs in explaining its conduct—it vindicated their tactical decision to leave approaching Petrov until after Beria’s downfall.

ASIO’S SECOND APPROACH TO PETROV

Petrov’s misery by early October 1953 was quite genuine. Ambassador Generalov arrived in Canberra on 3 October and had clearly read the files. Petrov sensed Generalov’s negative predisposition and within three days the Ambassador had submitted a negative report about Petrov to Moscow. (Petrov was shown the cable by one of his few friends at the Embassy, cypher clerk Pyotr Prudnikov.) We have independent evidence of Petrov’s state of mind here because he drowned his sorrows with Bialoguski, who maintained contact, despite being cut by ASIO. Petrov’s despair was increased on 20 November 1953, when Evdokia was sacked for reasons that remain unclear. Petrov now said it would be “better to work on the roads” in Australia—or to farm, a recurrent theme in his conversation—than to “live in daily fear of your life”. While the couple were contemplating suicide, Bialoguski felt Christmas had come early.

Bialoguski had got himself into what Manne calls understatedly a “rather delicate legal situation” in the weeks since his dismissal from ASIO: he had met another Soviet intelligence officer, ostensibly “offered” his services, and begun cultivating the man—without any official backing. Bialoguski had also been in contact with the Sydney Morning Herald, proposing to sell his story of infiltrating the Communist fronts that controlled the “peace movement” and his work with Petrov, whom he had mentioned by name. Had there been a Soviet agent at the Herald, or if there had been a leak from the newspaper, the Petrovs could easily have gone the way of Konstantin Volkov. Fortunately, neither was the case and now Bialoguski changed course.

Bialoguski got in touch with ASIO on 23 November to demand re-employment to complete Petrov’s defection, using his prospective story in the Herald as leverage (a cynic would say blackmail). The possibility that Bialoguski belonged to the Soviets, or was an unwitting agent of Petrov’s in a scheme to embarrass Australian intelligence, still concerned ASIO, but Bialoguski had a good hand. ASIO’s Director of Operations Ron Richards met with and re-hired Bialoguski on 27 November, raising his weekly wages.11

Bialoguski was now directly handled by Richards, rather than making contact with ASIO through intermediaries, and contact was much more frequent than it had been. Richards, in turn, was in close contact with Charles Spry, the Director-General of Security (head of ASIO), who took personal charge of the Petrov case at headquarters. Petrov’s defection now became the highest priority at ASIO, codenamed Operation CABIN 12. In early December 1953, a safe house was rented in Sydney to prepare for the seemingly imminent defection of Petrov and possibly his wife. There was a sense of deflation, however, when Bialoguski next met Petrov and reported that, though he was “still a worried man”, the “note of hysteria … at our last meeting had gone”. Bialoguski proposed, and ASIO approved, a series of active measures, so to speak, to get things moving.

On 12 December 1953, Bialoguski took Petrov to see the “Dream Acres” chicken farm outside Sydney on the pretext that Bialoguski had come into some money on the stock market and was considering buying the place. Bialoguski asked Petrov to accompany him to give advice, and during the visit had Petrov—using the assumed name “Peter Karpitch”—pretend to be his business partner, who would be co-owner if they purchased the farm. The aim was obviously to show Petrov the life he could have if he defected. On the drive home, Bialoguski offered to buy the farm, at a cost of £3,800 (equivalent to £130,000 today), for Petrov. Petrov said he needed time to think, and gave away no hint of seeing anything amiss, but, as Manne documents, “a crucial psychological line had been crossed”: Petrov must at this point have realised “there was more to Bialoguski than met the eye” and that “Bialoguski was now contriving in a scheme for his defection”.

Bialoguski’s “second gambit”, also approved by ASIO, was to arrange an “accidental” meeting between Petrov and Dr. Beckett outside the latter’s surgery on Macquarie Street. Manne explains:

Feeling himself and not ASIO to be in control of Beckett, Bialoguski’s view of the good doctor’s usefulness to the Petrov operation was now radically revised. His aim was now to boost Beckett in Petrov’s mind, to bring Petrov and Beckett together socially, and to use Beckett as the intermediary through whom Petrov would finally make contact with ASIO.

The two got on well, and on 23 December Petrov asked Bialoguski to arrange a lunch or dinner with Beckett. Bialoguski arranged this and the next day reported everything to ASIO, oddly believing they did not already know. Beckett, of course, had told them the moment he put the telephone down with Bialoguski. But this was part of the extremely complicated four-way relationship that existed at this point and provided the framework in which Petrov made the leap a few months later.

“In the strange triangular relationship of Petrov, Bialoguski, and Beckett, the question [was open] of who knew what about whom”, writes Manne. Beckett thought Petrov was “a disillusioned Polish Communist on the point of fleeing to London for musical and political reasons”, and that Petrov’s relationship with Bialoguski was simply that of a friend. What Beckett made of Bialoguski is more opaque. Bialoguski more-or-less knew Beckett was an ASIO agent, Petrov suspected it strongly, Bialoguski knew of Petrov’s suspicions, and Petrov knew that Bialoguski knew of these suspicions. Petrov had an inkling of Bialoguski’s ASIO connection after the Dream Acres episode, though how firm that suspicion was is impossible to determine. The fourth participant in this relationship, ASIO, had Petrov as its target and received reports on him from Bialoguski and Beckett independently, as well as their reports about each other.

PETROV LOSES FAITH IN THE SOVIET UNION

Petrov had a dreary Christmas in 1953. In the early hours of Christmas Eve, Petrov’s car had overturned in Canberra on his way back from a meeting with a spy he had recruited in the French Embassy, Ms. Rose-Marie Oilier. Petrov was nearly killed, but there was little sympathy from Ambassador Generalov, who made Petrov pay for his own replacement vehicle as he had not kept up the insurance on the old one. Whether this was because of a suspicion Petrov had been drinking (which he had not), was part of the general breakdown of relations, reflected a genuine irritation at Petrov’s bureaucratic slovenliness, or some combination of all of the above, it reinforced Petrov’s despondency and his darkest suspicions that someone at the Soviet Embassy was behind the crash as an attempt on his life.

Petrov was visibly in despair in the New Year, his former jovial nature replaced by a reticence and twitchiness. On 9 January 1954, Petrov’s first trip of the year to Sydney, he got very drunk with Bialoguski, and was taken back to the Dream Acres farm, whose baffled proprietors maintained their decorum in showing the two men around. On the journey back this time, Bialoguski was wearing a wire and when he asked Petrov if he planned to take over the farm, Petrov immediately answered “in April”. Pressed, Petrov specified “about the 5th”. ASIO now had a recording of Petrov expressing a desire to defect, which was not intended as blackmail—defectors secured thuswise are very messy for a counter-intelligence service—but as insurance, to neutralise their still-extant worst-case fears that the whole Petrov operation was a “wicked Bolshie plot”.

This development is devastating to the conspiracy theories about Menzies controlling the timing of events. Whether Petrov had fully defected in his own mind in early January 1954, it was the workings of Petrov’s mind that determined the date that was taking shape for his physical defection. Petrov was recalled to Moscow, and probably already had been by 9 January, with his replacement, E.V. Kovalenok, provisionally set to arrive on 5 April. Kovalenok was, like Petrov, only envisioned as a temporary rezident, with his main task being the creation of an Illegals network. Petrov’s nascent plan for defection involved following the handover procedure first.12

Petrov stayed at Bialoguski’s flat on 9 January and in the morning of 10 January—already drinking again—came into Bialoguski’s bedroom with a copy of the Sydney Morning Herald. After reading from an article on the social conditions inside the Soviet Union, Petrov added:

Look at that man! [Soviet Premier Georgy Malenkov] and his clique live in luxury, just as the Tsars did, while the masses of Soviet people grovel in poverty! Three million Russians refused to go home after the war. They were better off as prisoners of the Nazis! But if you go to Russia and say these things they’ll cut your head off! Look at Beria—killed after he himself had killed thousands Why shouldn’t Russians live and let live, open their frontiers, they can’t fool anybody anyway; foreign diplomats can see the whole thing for themselves. I will stay here, I will tell the whole truth, I will write a true story, I will fix those bastards.

This was the first direct evidence that Petrov had turned on the entire Soviet system, and was not merely angry about the Embassy intrigues that had caused his personal misfortunes. The quote—more precisely, a version of it—was to become rather central to ASIO’s version of events, giving Petrov’s defection a distinctly moral valence.

Victor Kravchenko—a Ukrainian-born Soviet military officer posted to Washington, D.C., as part Stalin’s U.S.-approved free-for-all raid on American industry under the Lend-Lease program—saw through Communism and defected in April 1944. Despite the advice of Joseph Davies, FDR’s Soviet-besotted chief adviser, that Kravchenko be handed over to Stalin’s killer squads, Kravchenko remained in the U.S., and in 1946 published a memoir, I Chose Freedom. This became the model for Western services handling Soviet defectors: the downsides to having a defector, rather than an agent-in-place, were offset by the opportunities for political warfare. And it was not wholly cynical.

Morality played a dominant part in some defections of Petrov’s era, such as that of Nikolai Khokhlov, who turned himself over to the CIA in West Germany in February 1954 when he could not go through with orders to assassinate the leader of a Christian anti-Communist émigré group.13 The embarrassment caused after Khokhlov went public on 22 April essentially ended the Soviet Union’s use of assassination abroad.14 Morality was less prominent with Yuriy Rastvorov, whose defection to the CIA in Japan was made public in August 1954. Rastvorov feared for his life in the post-Beria purges. Humans are complicated, though: morality does not stand apart from self-serving considerations, and over time the mix of motives can change. Many Soviet defectors came to emphasise the moral dimension. In speaking about it, they helped educate the West about the nature of the enemy and induce others in the Soviet Union to follow them, contributing to the difficulties for Soviet intelligence in furthering the Communist mission in the world, and keeping alive the idea of a Russia without Communism.

THE ENDGAME

Bialoguski took the initiative after Petrov’s 10 January 1954 outburst, and bluntly proposed to Petrov making contact with Australian intelligence, using the connection with Beckett. Petrov flaked on the meeting arranged for 15 January, but attended a dinner with Bialoguski and Beckett on 23 January, where Bialoguski subtly left the room, and Beckett told Petrov he could arrange a stay in Australia with financial and physical security. ASIO was now keen to make direct contact, and Richards briefed Beckett to this effect on 28 January. Richards then wrote to Colonel Spry that the operation, now in its “most crucial stage”, had to tackle the final barrier to Petrov’s defection: Evdokia.

ASIO had been unable to get a read on Evdokia during all of its time surveilling Petrov. Petrov asked Bialoguski to sound out his wife about the possibility of staying in Australia, which Bialoguski did during a trip to Sydney on 30 January. Acting under instructions from Spry to make the approach “very general and tentative” to avoid compromising himself, Bialoguski found Evdokia “formally” indignant about the idea of defection, vociferously expressing her belief in Communist theology, and worried about her mother and sister back home (she was less concerned about her father and brother). In the “informal” part of the conversation, Evdokia was rather consumed with the dress sense of Queen Elizabeth II, whose coronation had taken place seven months earlier. Petrov was disappointed, as was ASIO, which had no more understanding of the Evdokia enigma blocking their operation than they started with, but Bialoguski’s cover had not been blown, so at least the operation remained intact.

As ASIO awaited developments, Spry composed a paper, ‘Considerations Concerning a Possible Soviet Defector’. Comment was requested from Solicitor-General Kenneth Bailey and Alan Watt, the recently-departed Secretary of the Department of External Affairs (DEA, i.e., Foreign Ministry). The government was now made aware of the likelihood of Petrov’s defection. Spry took his paper to Canberra, where, on 9 February, it was discussed with the Minister of External Affairs Richard Casey, Watt’s successor Arthur Tange, and Attorney-General John Armstrong Spicer. Spry met Prime Minister Menzies on 10 February.

Interestingly, it was Professor Bailey who was the most “hawkish”, suggesting that the Australian government play hardball over offering Petrov asylum, now that Petrov had put himself in danger. Asylum should not be granted automatically, said Bailey, but should be contingent on Petrov providing valuable intelligence. It was also Bailey who saw the chance to make Petrov’s defection into what we would now call a teachable moment, suggesting holding a Royal Commission as “a fruitful means of propaganda”, and made a direct reference to Canada’s handling of the Gouzenko case. Spry was agreed that a Royal Commission was an excellent way to educate the public about Soviet espionage. As expected, the diplomats at DEA were the most trepidatious, hand-wringing about possible Soviet retaliation against the Australian Embassy in Moscow. Watt even worried aloud whether the Soviets would “disappear” one of the Moscow Embassy staff. Tange was less fearful, though no less finicky, hung up on the matters of protocol when the Soviets inevitably asked for access to their citizens.

Spry sent around a detailed plan how ASIO would run the defection on 17 February. Spry split the difference on Bailey’s version of hardball, offering Petrov protection and pay—and a farm if he wanted it (Dream Acres was still on the table)—without making these blandishments quite hinge upon Petrov giving up everything he knew, even if such a course was to be strongly suggested. Information from Petrov was to be taken in a form admissible in court. The safehouses were to be kitted out to cope if Evdokia defected as well. Known KGB officers at the Embassy, the TASS facilitator, and Moscow’s agents in the front groups Bialoguski had infiltrated were to be placed under surveillance, as was Bialoguski himself: ASIO’s suspicions about him had not abated. Bialoguski would get an “honorarium” of £500 (£17,000 in today’s money), shares of the profits from any book published about the Petrov case, and continued employment with ASIO—so long as he did not talk to the press, which really was the point of all this. It was hush money. It was decided the short prepared statement on the defection would be issued by the DEA. Finally, showing something of the mood of the moment, a quixotic ASIO briefing was given to the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) police to prepare themselves to handle a possible torrent of defectors from behind the Iron Curtain after the announcement was made about Petrov.

Bialoguski brought Petrov to a meeting at Beckett’s home on 19 February with the express purpose of getting in contact with Beckett’s “friend” in ASIO. After a round of drinks, Bialoguski asked Beckett on Petrov’s behalf about setting up a meeting with his ASIO contact, by now named as Richards. Beckett made sure to stress—for the sake of Bialoguski’s wire—that Petrov had to approach ASIO; the Commonwealth would not approach a foreign official. Beckett then telephoned Richards within earshot of Petrov and arranged a meeting for the next day. A toast was drunk to Petrov’s future in Australia, and Petrov and Bialoguski then set out in search of girls.

Petrov, however, left Bialoguski’s flat on 20 February before Richards arrived, and declined the offer relayed by Bialoguski for immediate “assistance”. Nor did Petrov attend the rearranged 26 February meeting. Unlike in August-September 1953, ASIO did not go into a funk about Petrov. The steps Petrov had already taken—including beginning to gather documents, some of which he had been entrusted to destroy—made it more likely than not that he had crossed the Rubicon. Headquarters understood Petrov needed to be slow-walked over the finish line, and ASIO—for all its doubts about Bialoguski’s ultimate loyalty and its belief in the disreputable nature of his motives—had confidence Bialoguski could get the job done.

When Petrov returned to Sydney on 27 February 1954, Bialoguski picked him up from the airport and began working him at once. ASIO had been concerned about his safety, said Bialoguski. There was no obligation in the meeting with Richards, Bialoguski went on: it had been made clear it was an “unofficial” contact. “Nobody has authority to force you to remain here”, said Bialoguski. “Don’t think there is any blackmail”; that was not the way of “Englishmen”, as Bialoguski referred to Australians. By 18:25, Petrov’s resistance was worn away: he told Bialoguski to telephone Richards, and Richards was soon at Bialoguski’s flat for ASIO’s first face-to-face meeting with Petrov.

At this first meeting, terms were hashed out: Petrov would be given full security and the Australian Commonwealth could extend up to £10,000 (£350,000 now). Bialoguski, ever-attentive to such matters, asked whether Petrov’s living expenses would be deducted from this sum. Richards assured him they would not. Petrov asked if the Commonwealth would object to a book or newspaper series. Richards said that, on the contrary, ASIO would encourage Petrov to write such things—it would be proof to them he had left “this other business” behind—and ASIO would even help writing them. Curiously, when asked about his position, Petrov omitted that he was the MVD rezident. The question of Evdokia was brought up. Petrov thought it was “50-50” she would come with him. As base as Petrov and his motives can seem when the story is examined closely, he was under no illusions the risk he was taking. “Oh, they would kill me”, Petrov said when Richards asked what would happen if Evdokia discovered his plan to defect and told the Ambassador.

After the meeting, Richards and Bialoguski came to the same conclusion: Petrov had been obviously nervous and remained skittish; he needed something “tangible”. On 3 March, ASIO signed-off on £5,000 (£170,000 now) and it was decided that Richards would show this to Petrov, in bundles of £10 notes, when they next met, which Richards did on 19 March in Bialoguski’s flat. At this second meeting, Petrov was much more sure of himself, sure he would defect, and sober (amazingly). Petrov mentioned documents and—when Bialoguski was out of the room—said they disclosed Australians who were spying for the Soviet Union. Richards made clear that if valuable documents on Australian traitors were brought to him, Petrov’s £5,000 would be doubled. But Richards also warned Petrov against taking any unnecessary risks to acquire documents.

Later pro-Labor conspiracy theorists would say the delay between the 27 February meeting and the 3 April defection was because ASIO was concocting documents with Petrov. Manne dismisses this. The 19 March meeting was the first mention of documents, and Petrov raised the issue. On the other hand, as can be seen with Richards’ offer to double the lump sum given to Petrov, ASIO was slightly misleading at the later Royal Commission in maintaining that there was no link between money and the provision of documents.

At the 20 March 1954 meeting in the Sydney safehouse between Petrov and Richards—their first without Bialoguski, arranged when he had been out of the room the day before—they talked espionage. Petrov confirmed there had been “very serious” Soviet penetration of the DEA during the Second World War, that at least one senior official had been a spy, and that the Australian Communist Party had been “involved in this business”. A notable part of this meeting was Petrov apologising for Bialoguski’s behaviour: “The doctor talks a lot about money for me. I am not worried about that—I trust you to take care of me.”

Petrov and Richards met again on 21 March, the third time in as many days, once again in Bialoguski’s company. The main outstanding issue was Evdokia. Petrov said she was worried about her family within the Soviet Union, and about their fate if they defected: “My wife says that we are like the Rosenbergs if we stay”, said Petrov, referring to the American traitors, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who had been executed on 19 June 1953. It was at this meeting that Petrov decided to defect without Evdokia. The plan was for ASIO to approach Evdokia with a note from Petrov as she left the country, but Petrov’s defection would not be announced until after Evdokia had left to avoid any Soviet attempt to use her as a hostage, or in the worst-case kill her in the Embassy. Only the practicalities remained. Petrov said Bialoguski would retrieve his beloved Alsatian, “Jack”, which Richards did not much like, but Richards’ focus was drawn more to Petrov setting a tentative date of 2 April for the defection, after a handover to his successor.

Richards had told Petrov on 21 March that he could defect there and then; he merely had to sign the form requesting political asylum. A day or two to tidy up, and perhaps collect more documents, would have been reasonable. Two weeks absolutely was not, in Richards’ estimation. But in the meetings on 23, 25, and 26 March, Petrov moved from evasiveness about his defection date to insistent on 3 April, and nothing Richards said about the danger this was putting Petrov in budged him, not even after a note was sent to the Soviet Embassy suggesting part of Petrov’s plans had leaked. The source of the note was never traced. Richards and Petrov had a brief meeting on 30 March, and on 31 March Petrov’s hand was finally forced: after an Embassy party, charges were brought against Petrov, one of them insubordination, and Petrov’s desk and safe at the Embassy had been raided, with documents discovered there out of place, though fortunately not the documents he had been gathering to defect with.

At a panicked meeting on 1 April, Petrov told Richards he would travel to Sydney the next day and never return to the Embassy, that he would at last sign the request for political asylum Richards had been carrying for a month, and meet with Colonel Spry. Overnight, 1-2 April, ASIO kept watch on the Soviet Embassy to see if there was any unusual movement indicating a move against Petrov.

After flying to Sydney on 2 April, Petrov had another brief meeting with Richards in the flat where they had met on 20 March: Petrov unfolded a copy of Pravda to show Richards some of the documents, in English and Russian, that had been taken from the Embassy. Petrov at last mentioned that he was an MVD officer. Richards left Petrov at the flat at about 16:00, as Petrov wanted to sleep, and when Richards returned, at 18:00 on 2 April 1954, Petrov finally signed the request for political asylum. Just after 20:00, Colonel Spry called in to meet Petrov for the first time. Petrov stayed overnight 2-3 April at Bialoguski’s flat. Bialoguski had been out-of-the-loop since 21 March, and the plan was to ensure he remained so.

Petrov left Bialoguski’s flat in the morning of 3 April 1954, and Manne describes the final day:

[Petrov] went to Mascot to greet a Soviet party, which included his successor Kovalenok. Kovalenok’s first words on the surface were reassuring. All would be well for him when he returned to Moscow. Petrov, who had been a member of [Soviet intelligence] for more than twenty years responded privately to these assurances with alarm. His worst fears seemed confirmed. An ASIO party, which included Richards, picked him up at Mascot. Petrov, however, had one final official task to perform—a handover of money at the Kirketon Hotel to a Soviet party on its way to New Zealand.

Arrangements to drop him off and pick him up were improvised hastily. Richards looked on anxiously as Petrov, document-satchel in hand, left him once again. When he completed his work at the Kirketon, Petrov, suspended for a moment between his past as an intelligence officer and his future as a defector, had a beer or two in freedom … [then] returned to the waiting ASIO car (inside which nerves were on edge) and was driven to the safe house on Sydney’s north shore. On arrival Richards handed Petrov £5,000 and Petrov passed Richards the documents in his satchel. He had now defected.

DEBRIEFING PETROV AND RESCUING HIS WIFE

Petrov was debriefed for six hours on 3 April, writing twenty pages about his life and career at the Soviet Embassy, and about the documents he had brought with him. Even once translated, some of the documents were difficult to make out without Petrov’s explanation. The documents dated from 1943 through Petrov’s time as acting rezident.

An immediate find that was to become famous as “Document J”, written inside the Soviet Embassy by the Communist “journalist” Rupert Lockwood in May 1953, named the sources Soviet intelligence had in the Australian press corps. One of them was Fergan O’Sullivan, the press secretary for the leader of the Labor Opposition Herbert Evatt since April 1953. There was also “Document H”, written by O’Sullivan. It was clear as crystal O’Sullivan was a Soviet spy and the information he had passed to Moscow when he worked at the Sydney Morning Herald was assessed by the Centre as valuable. Rather tellingly, while O’Sullivan was sympathetic to the Australian Communist Party—that much was obvious to ASIO, which had met Evatt twice over its concerns about O’Sullivan’s associations—he had never been a formal member. So far from being an exculpatory fact, this is an indication of O’Sullivan’s importance to the Centre, which advised those it had talent-spotted as potentially high-flying agents to abstain from any direct ties to the local “fraternal” Party.

The information about O’Sullivan was taken to Prime Minister Menzies on 4 April by Spry and Richards. Menzies does not seem to have known who O’Sullivan was; his main concern was to get Petrov’s documents translated. Spry very likely raised the issue of a Royal Commission at this point. Menzies was somewhat sceptical, but Spry’s arguments—the Canadian precedent, producing a report highly esteemed by all Anglosphere services; the legal necessity, since ASIO could not subpoena those who must now be asked questions; and the vital chance for public education, at a moment when the consciousness of the Communist problem had somewhat dipped—won Menzies around. By 11 April, when Menzies was sent the list of names of Australians the KGB had codenames for—not all of them spies—he was sure a Royal Commission would be needed.

11 April was also the day the Soviets sent two KGB “couriers” from Rome to bring Evdokia and Philip Kislitsyn, another KGB Legal and a seeming friend of Petrov’s, back to Moscow. The Embassy had realised quite quickly what had happened,15 and the games were ended on 13 April, when Prime Minister Menzies told his Cabinet about the defection in the morning, told the Soviets at midday, and told Parliament—and thus the nation—in the evening. At the Cabinet meeting, Menzies had informed his colleagues there would be a Royal Commission, and he explicitly banned any public mention of the spies uncovered, including O’Sullivan, before the election. This honourable conduct was twinned with the mischievous decision to delay the announcement in the House until after Evatt had taken a scheduled flight to Sydney, leaving Labor in some disarray in responding to the news.

Some would later see this discourtesy as impactful on Evatt’s reaction to the Petrov defection, but this mixes up cause and effect. Evatt, like so many on the Left throughout the whole Cold War, simply did not take Communist subversion seriously, part of what had allowed such a serious security problem to develop in his own office (see below).16 It was the government’s knowledge of this counter-intelligence problem—of the company Evatt was keeping, in outline if not in the specifics—that meant the Leader of the Opposition was not trusted with a classified briefing as Petrov’s defection neared, and that was why Evatt was surprised by the news. At root, Evatt only saw Communist subversion as a problem to the extent it was used by the Right—a view held so strongly Evatt could not fully hide it.17

The Soviets publicly claimed Petrov had been kidnapped on 15 April. Dismissing this as “ludicrous”, Menzies remarked that it would be the “singular good luck” of ASIO to have “pick[ed] up the victim at the very moment he was walking down the street with some hundreds of documents”. The Soviets had not even officially asked for access to Petrov.

The last act of Operation CABIN 12 was to be a direct approach to Evdokia and Kislitsyn. Knowing what flight they were leaving on, ASIO brought Britain’s MI5 into the operation so the approach could be made during the stopover in Singapore. The rending of garments in the External Affairs Department about “Australia-Soviet relations” after Petrov’s defection was already overwrought, bordering on undignified; another defection (or two) in Australia was considered more than the constitutions of senior DEA officials could bear. Petrov prepared the way by sending notes, on 16 April (Good Friday) and 17 April, respectively, asking to meet his wife and encouraging Kislitsyn to “take the path of freedom”.

Generalov forced Evdokia to write a reply saying she would not meet her husband as she feared an ASIO trap.18 As with so much Soviet discourse, the kidnapping accusation against Australia was projection. Evdokia and Kislitsyn, after thirteen days locked in single rooms at the Embassy, were dragged to Mascot Airport in Sydney on the evening of 19 April, flanked by the two KGB “couriers” and “First Secretary” A.G. Vislykh. Though the Soviets had decided to use commercial air traffic, Evdokia was told she would be shot if there was any attempt to escape and the KGB minders were armed. ASIO had officers, led by Richards, stationed in a room Evdokia and Kislitsyn had to pass through in case either wanted to make an application for asylum before leaving, and Petrov was hidden at the airport, too, in case his wife demanded to see him as proof he was safe.

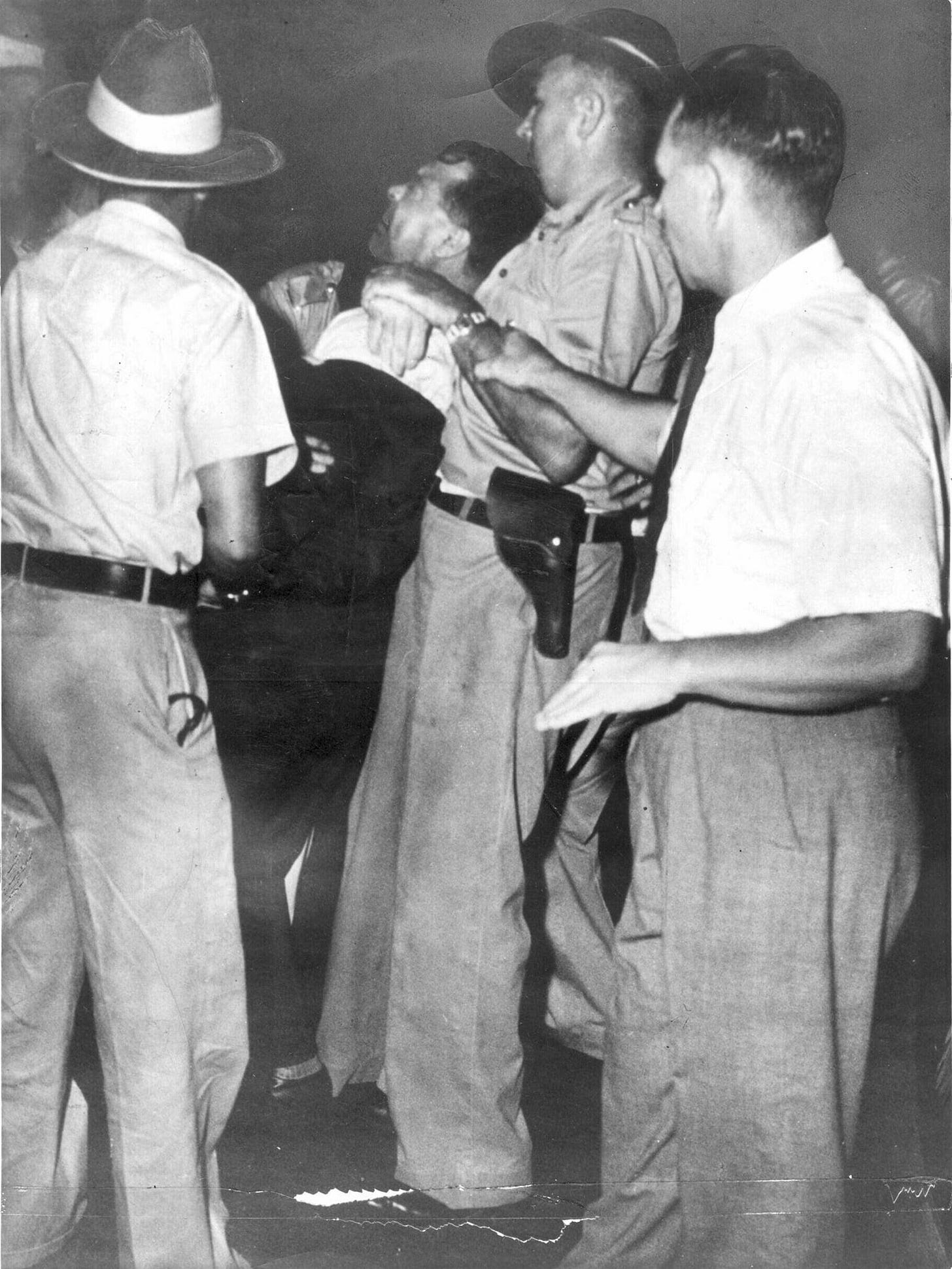

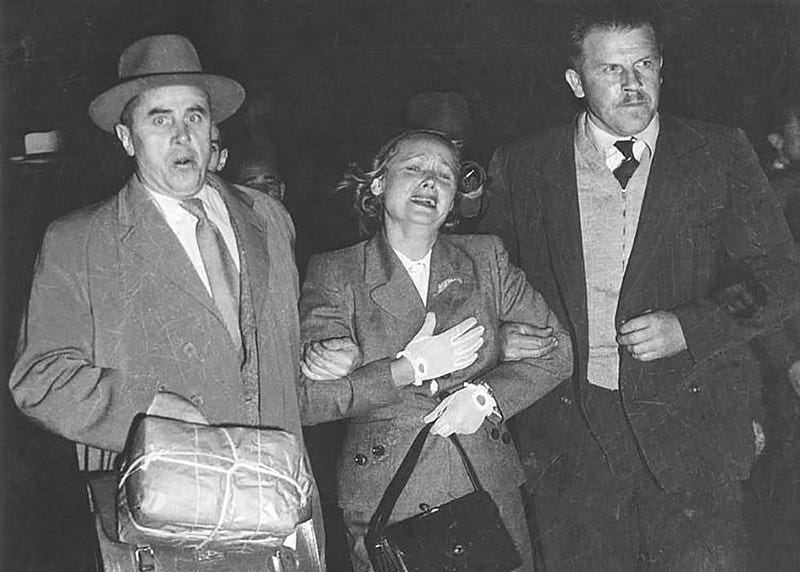

Meanwhile, outside Sydney Airport, a large crowd, mostly of refugees from the Soviet Union and the Captive Nations, were boisterously protesting what they (correctly) saw as an attempt to forcibly transfer two people to a dreadful fate. Chaos broke out after Evdokia and Kislitsyn were taken through the wrong gate, to domestic flights rather than international, bypassing the room with Richards’ team in, and the Soviet party was then confronted with a rioting crowd that had broken through the fence. Evdokia and Kislitsyn were narrowly pulled onto a plane as the refugee demonstrators tried to free her, as they saw it. Evdokia was the particular focus of the crowd, doubtless for subliminal “damsel in distress” reasons, and she was certainly hurt as she got onto the plane by her guards holding her so tightly. Whether it was just a shout of pain, or she had called out for help, witnesses were divided upon.

At about 22:00 on 19 April, Menzies ordered ASIO to make the direct approach to Evdokia and Kislitsyn at Darwin Airport, where the plane would have to land to refuel, and the Prime Minister announced this intention in a press conference shortly after midnight. Spry managed to get in touch with the plane captain, who confirmed Evdokia was hurt, frightened, and had explicitly told him she wanted to stay in Australia. Using the legal pretext of the Soviet “couriers” carrying weapons on a plane—illegal under Australian law and not protected by diplomatic immunity—ASIO now had grounds to approach and disarm Evdokia’s and Kislitsyn’s guards. It was hoped the guards would stand down peacefully; it was possible there was about to be a shootout at an Australian airport.

When the plane landed in Darwin at 05:00 on 20 April 1954, all passengers had to leave during refuelling. The Soviet party was the last. Confronted immediately by the ASIO team and local police on the tarmac, there was a scuffle after one of the KGB couriers tried to reach for his gun. The other minder put up rather more token resistance. Kislitsyn contemptuously rejected the offer of asylum there and then. Evdokia was paralysed by indecision; she knew nothing good waited for her in Moscow, but she was not sure her husband was alive. She asked the Australian official speaking to her if he could not make the decision for her and kidnap her. It was suggested that letting Evdokia speak to Petrov on the telephone was the easier option, which she did at about 07:00, insisting it be in the room with her minders. After the call she loudly announced that was not her husband, who was already dead, and she would be returning to Moscow—though she winked at the Australian official who had previously questioned her. With one last throw of the dice, Evdokia was asked if she would like a private meeting—an offer she had refused once—and this time she accepted. Evdokia said she wanted to stay in Australia, but would sign nothing until she had seen her husband. Kislitsyn and the KGB officers flew home. Evdokia was reunited with her husband.

The mood was euphoric in Australia—and beyond. In the Anglosphere, especially, it was a clear-cut case of good triumphing over evil, of light over dark. “The fearless Christian action of the Australian government” has “lifted high the torch of freedom the world over”, British Conservative MP Conservative Henry Kerby wrote to Menzies, expressing the popular sentiment of the moment. The Soviets summoning the Australian Ambassador in Moscow on 23 April and telling him his mission had to leave the country within three days, then recalling their Embassy in Canberra, brought an apocalyptic mood to the DEA, but for everyone else the severance of Australia-Soviet diplomatic relations only added to the sense of righteousness about what had been done.

THE PETROV AFFAIR

The 29 May 1954 Federal Election, which a Gallup Poll in March had predicted favoured Labor, went Menzies’ way, albeit quite narrowly, his 69-52 majority reduced to 64-57. For this, Evatt and many Laborites would never forgive Menzies. The Petrov defection was declared a modern “Zinoviev Letter”, or, by the more distraught comrades, a Reichstag fire. This is nonsense. It was silly to suggest Menzies could have avoided announcing the Petrov defection before the election—the Soviets would have thrown their very public fit in mid-April no matter what Menzies did. All that would have been achieved by not announcing it on 13 April was that the Soviets would have been able to shape the narrative by announcing it first.

Moreover, it is simply untrue that Menzies used the Petrov case as a weapon during the campaign. With the exception of one vague leak on 18 April about Labor officials implicated in the Petrov revelations, and one false American-sourced story four days later about Labor MPs being recruited as agents, there was nothing in the press to damage Evatt from the Petrov defection. Neither of these stories swung the election and more to the point, as Manne concludes, “The self-denying ordinance Mr Menzies and his Cabinet swore on April 13 concerning the suppression of names mentioned in the Petrov documents was scrupulously maintained throughout the period of the election campaign.”

Lockwood’s role in authoring “Document J” soon became public and to pre-empt the next revelation, O’Sullivan confessed to Evatt about his treachery on 3 June 1954, whereupon he was immediately fired. From Manne again:

Progressively from this moment, Dr Evatt … abandoned himself to the darkest suspicions concerning real and imagined enemies and to an absolute faith in his powers of intuition. … Politically speaking, this is the turning point … Without Dr Bialoguski there may have been no Petrov defection. Without Dr Evatt there would have been no Petrov Affair.

The Royal Commission on Espionage, set up in April 1954, held its first post-election hearing a week after O’Sullivan’s resignation.19 Commission hearings ran until August 1955. The final report was published in September 1955. The Petrov documents were authenticated by the Royal Commission, as was the extensive Soviet espionage in Australia they revealed: the recruitment and even heavier surveillance of émigrés, the political influence operations through co-opted politicians and journalists, and—up to at least 1948—grave breaches in government departments, particularly External Affairs. Through O’Sullivan, the Soviets had nearly acquired a spy at the heart of the Australian State. The capture and disclosure of Soviet tradecraft—inter alia, how Moscow used Embassies, “journalists”, and the “fraternal” Communist Parties—allowed Australia and her allies to be more successful in guarding against such breaches.

Petrov’s documents had limitations because of compartmentalisation—Petrov saw little of the GRU network that handled some of the more military matters and essentially nothing of the Illegals network—but the outline of Soviet priorities, practice, and progress was there. Canberra had not fully appreciated that access to British and American intelligence and military plans, notably during the Korean War and over Red China more generally, put Australia so high on Moscow Centre’s list. After Petrov, Australia became fully seized of the fact that its access to, and role in formulating, Anglosphere political-strategic decisions affecting the Communist powers meant it was seen by the Centre as an adjunct to the U.S., with all that entailed in terms of the scale of Soviet espionage. The Soviets, of course, were equally interested in discovering—and exacerbating—any differences within the Anglosphere. Then there was the constant hunt for science and technology.

What the Royal Commission is mostly remembered for, however, is Evatt very publicly losing his mind before its investigators. O’Sullivan’s confession meant Evatt could not quite go down the line of American fellow travellers, whose outright denialism that Alger Hiss and Ethal Rosenberg were spies persists to this day. Instead, Evatt came to believe O’Sullivan had been planted on his staff, and that a conspiracy had been unleashed against him involving Menzies, ASIO, and Catholic anti-Communists within the Labor Party grouped around the Catholic Social Studies Movement and its leader, B. A. Santamaria, the towering figure of Victoria Labor politics.

It was at the Royal Commission, during the questioning of O’Sullivan in mid-July 1954, that it was revealed the full translation of “Document J” showed there were two more Soviet spies on Evatt’s staff: assistant secretary Albert Grundeman and his private secretary Allan Dalziel. Evatt took this as a personal affront, a vindication of his claims that the Commission was an instrument of “McCarthyism”, a “witch-hunt” and a “show trial”, controlled by Menzies. Evatt’s sense of reason on this front was not helped by him being banned from appearing before the Royal Commission on 7 September 1954 after he made a series of extraordinary attempts to derail the evidence-gathering process with his conspiracy theories.

Evatt had said he said he would represent Grundeman and Dalziel before the Commission, and began what was formally a cross-examination of O’Sullivan on 16 August 1954 that quickly spiralled into the presentation of an elaborate theory that O’Sullivan was an author of “Document J”, as well as of “H”, as part of a “conspiracy”—he used the word directly—against him, Evatt, to sway the 1954 election, rather than any effort to pass information to the Soviet government. The commissioners who expressed scepticism, or simple bewilderment at what was happening, were attacked for creating a “political … atmosphere”. Evatt was given access to the whole of “J” a few days later, declaring triumphantly he had proven it was not written by Lockwood, and by this time Lockwood was at it, too. Dropping his initial claim to have written parts of “J” that had been “recast”, Lockwood now said he had not written a word of it. Evatt got lost in an excursion about how the document was stapled together, at one point said “J” was a forgery, and eventually said Petrov was O’Sullivan’s co-conspirator and, indeed, blackmailer. Evatt was oddly cautious in only accusing Richards of “negligence” in not detecting the forgery. It was self-contradictory and, frankly, mad. The commissioners were given access to cotemporaneous ASIO reports, Beckett, and Bialoguski, which quickly collapsed Evatt’s position(s), leaving him raving outside the court about a “Police State”.

Menzies had been unnerved that Evatt was succeeding in destroying public perceptions of the Petrov case. Evatt’s colleagues were worried he was destroying them; he had not even told them he was going to the Royal Commission or left any instructions for the party on Parliamentary business. The Santamaria wing of Evatt’s Party had had enough by March 1955, and broke away to form the Australian Labor Party (Anti-Communist). Evatt’s erratic behaviour got worse over the next year, until in August 1955 he directly accused ASIO and Menzies being part of the conspiracy to not only cost him the 1954 election, but set up a “secret police” that repressed non-conformity in Australia.

The end of the line for Evatt was 19 October 1955, after the Royal Commission report, when Evatt got up in the House of Representatives to say that Menzies’ government had made three foreigners (the Petrovs and Bialoguski) rich, while “the nation has suffered heavy loss in trade, and the breaking of diplomatic relations with a great power”; engaged in “corrupting … an officer of a foreign government” for political purposes unrelated to security in a way that was “unprecedented in British countries”; and Evatt could prove the Petrov documents that allowed this abuse of power were fabricated, because Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov—Stalin’s most loyal representative to the world, the man who signed the pact with the Nazis to start the Second World War—had told him so. “For a moment the House sat in stunned silence … Then the House erupted in … laughter from both sides.” Evatt soldiered on through the taunts, laying out a vast conspiracy. When Evatt finally stopped talking, large numbers of his own MPs literally had their heads in their hands.

Menzies rose to the occasion a week later, on 25 October. Speaking to the House, Menzies refused to be drawn into a point-by-point refutation that would make it seem there was something in what Evatt had said, and spoke as an elder statesman, as much in sorrow as in anger, that someone previously so respected had behaved so irresponsibly:

The Leader of the Opposition has, from first to last in this matter, for his own purposes, in his own interests and with the enthusiastic support of every Communist in Australia, sought to discredit the judiciary, to subvert the authority of the security organization, to cry down decent and patriotic Australians and to build up a Communist fifth column. I am, therefore, compelled to say that in the name of all these good and honourable men, in the name of public decency, in the name of the safety of Australia, the man on trial in this debate is the right honourable gentleman himself.

Menzies was speaking for more than just Australia. ASIO acquired great prestige for managing the Petrov defection, around the world and particularly with its Five Eyes partners. As a recent assessment after the declassification of documents in the Petrov case explained, “The dividends lasted decades. The intelligence supplied by the Petrovs’ helped Western intelligence agencies identify hundreds of Soviet operatives around the world, as well as providing invaluable insights into Russian tradecraft.” ASIO, just half-a-decade after its founding, was more trusted by the Americans, the lynchpin of the entire Western Alliance, than British intelligence, the source of the “Cambridge Five” breach, the damage from which was still being assessed and repaired in 1954. The British position was not helped by the evidence from Petrov that several British diplomats had spied for the Soviet Union.

In terms of Australia, the effect of the Petrov Affair on her politics would last more than a generation. The Split had led to the spectacle of Evatt’s Labor colleagues decrying their (former) leader supporting Communists and traitors. The door was wide open for Menzies to call a Federal Election in December 1955, where Evatt was harried from meeting to meeting by shouts of “Molotov”. Menzies increased his majority to 75-57 in the House. Evatt still would not call it quits, and was only finally dislodged after taking Labor to a worse defeat in November 1958, an election amid a pretty serious global economic downturn that damaged incumbent governments almost everywhere else in the West. Evatt’s departure in 1960 alone could not undo the damage, though: the Labor Split was not automatically healed, nor was the public perception that Labor was unserious on national security undone. Labor’s next election victory was 1972, and even that was fleeting. It would take until the 1980s for Labor to seriously return to power.

REFERENCES

Gouzenko’s defection, two years before the loyalty-security programs began in the U.S. and five years before Senator Joseph McCarthy—that godsend for the Soviet Union and its fellow travellers—appeared on the (inter)national stage, revealed to Canadians the vast scale of Soviet infiltration in their country. The two-dozen prosecutions included Communist Party members, including an MP, and some Soviet agents in the military. The documents Gouzenko brought with him also contained hints of how bad things were in the U.S., specifically pointing to the State Department and (though he was not named) Alger Hiss.