The Russian Terrorist-Revolutionary Movement, 1866 – 1876: Nihilism, “The People”, and Defining Terrorism’s Purpose

Sergey Nechayev, the “Going to the People” Experiment, and Pyotr Tkachov

Previous articles in this series have covered the ideology of the Russian intelligentsia, the seedbed of the terrorist-revolutionaries; the 1825 Decembrist Revolt, the starting point of the revolutionary movement in Russia; and the formation of the Russian intelligentsia in the 1840s and its development into the 1860s. This article will look at the revolutionaries’ turn to terrorism in the 1860s. The next articles will examine: the expansion of the revolutionaries’ violence up to the Tsar’s murder in 1881, the State striking back and the entry of Marxism onto the Russian scene thereafter, and the culmination of the struggle in revolutionary triumph in 1917.

The Russian intelligentsia had emerged in the 1840s dedicated to the overthrow of the entire structure of Tsarism. The logic of cumulative radicalisation implanted by literary critic and novelist Nikolay Chernyshevsky had dictated a turn from literary agitation to active revolutionary methods, specifically terrorism, the objections of leading intelligént Alexander Herzen notwithstanding. The result was the first attempt to assassinate a Tsar in April 1866 by Dmitry Karakozov. This was the onset of a new phase of the Russian revolutionary movement.

Karakozov had not acted alone: he had been part of a secret revolutionary group, run by his cousin, Nikolai Ishutin, whose death sentence in 1866 was commuted by the Tsar (a detail those who present the Imperial Government as a proto-fascist regime might take note of). By some accounts, the group was founded in 1863, with an inner core called “Hell” and an outer circle called simply “The Organisation”. In truth, thanks partly to Ishutin’s wilful mystification, nobody really knows the structure of the Ishutin Society, even all this time later. It seems very unlikely, for instance, that the Society was one faction of a “European Revolutionary Committee” with branches in every State in Europe awaiting the order to murder their monarchs, as Ishutin told his cadres,1 but the Russian terrorist-revolutionaries would become highly integrated into a transnational infrastructure that extended as far west as Britain,2 and it is not impossible international links of some kind were forged in this period.

What is clear is what the group stood for. In ideology: socialism, violence as a virtue, and revolution to thwart industrialisation and constitutionalism in Russia, an idea that would gain increasing salience for the intelligentsia. And the conduct of its members accorded to the principles of Chernyshevsky’s “New Man”: self-sacrifice, ascetism to the point of renouncing family ties and not marrying, and the rejection of all conventional morals, expressed most clearly in its unscrupulous fund-raising methods (namely robbery; one member even planned to murder his father for the inheritance) and its use of deception (not least against its own members).3 The group, a component of the Russian Jacobin stream, was devoted to conspiracy in bringing off revolution and the rule of a despotic minority afterwards, with “Hell” at the centre of the new regime and the (largely non-existent) “Organisation” staffing the State. The economy would be nationalised, counter-revolutionaries exterminated to ensure equality, and officials in the new government who fell short would be removed by assassination.4

The Ishutin Society’s plans were exposed in open court by its members, as was the incompetence of the group. Most Russians were horrified, including the intelligentsia—initially. As the shock wore off, more and more of the intelligentsia came to see the Ishutin group as an inspiration, no-one more so than Sergey Nechayev, whose rise to prominence three years later was enabled by this change in mood.

THE LIVING LEGEND AND LASTING LEGACY OF SERGEY NECHAYEV

If people have only heard of one nineteenth-century Russian revolutionary, it is almost certainly Nechayev, and this quality of legend around him is something that existed contemporaneously. Nechayev’s presence was felt widely—in his own time and over the whole terrorist-revolutionary movement as it developed after him—and yet he was a shadowy, mysterious figure. The facts of Nechayev’s life, the content and sources of his ideology, and the influence it exerted: all of this is well known, as is the hypnotic spell Nechayev exerted over the few people who knew him directly. But a century-and-a-half later historians are no closer to finding the man himself. “Horror, fascination, awe, and reverence”: separately or in combination, writes Tibor Szamuely in The Russian Tradition, these reactions to Nechayev by his own revolutionary comrades have echoed down the decades. No matter how often Nechayev has been denounced or his memory repressed, there he still is, refusing to fit into any of the categories that contain the other ideologists and terrorists who put Russia on the path to the abyss of 1917.5

Nechayev’s Path to Revolution

Nechayev, born on 2 October 1847 (N.S.) to a serf and spending time working as a waiter, had “probably the most genuinely proletarian background” of the prominent Men of the Sixties, says Szamuely. Nechayev was educated in a fashion and his first serious job, from age-19, was as a religious teacher,6 an interesting parallel with his idol Chernyshevsky coming from a clerical family. The imprint of Christianity on the Russian revolutionary movement in general is profound. Nechayev was in Saint Petersburg when the Emperor was shot at in 1866 and reacted by declaring the event to be “the foundations of our sacred cause”, vowing to act so that Karakozov’s attempt would be remembered “as a prologue”.7 Nechayev joined the revolutionary milieu in late 1868 by becoming a “casual student” (i.e., attending lectures without being formally enrolled) in the natural sciences department of the university. Importantly, this was months after the accidental death of Dmitry Pisarev, the most serious ideologist of Nihilism in the intelligentsia, which created practical and ideological space for Nechayev. What Nechayev wanted to do was to forge relations with the radical intelligentsia among the student body and the revolutionary conspirators in their orbit, and that he did easily enough, even in this period of “repression”.8

The most important contact Nechayev made was Pyotr Tkachov (see below),9 with whom he would write a pamphlet in late 1869, Program of Revolutionary Action. Though drowned out at the time amid the wide circulation of revolutionary documents, the Program—with its call for political revolution to enable social revolution, its emphasis on conspiracy by “professional revolutionaries” to bring this about, and its ascetic vision for these conspirators (divorced from family, possessions, and sex) that extended beyond Chernyshevsky’s proposals for the “New Man”—set out in embryo the ideas Nechayev and Tkachov were to develop, which would dominate the ethos and practice of the revolutionary movement in its last forty years.10

In January 1869, Nechayev “disappeared”. This was common enough among the comrades, but Nechayev had left a crumpled note, apparently thrown undetected from a police van during his arrest. Then Nechayev managed to escape prison. Who could fail to be moved by the cunning and bravery? Except that it was not true—not a word of it. Nechayev, starting as he meant to go on, used deception even against his “own” people to establish his legend. With this story behind him, Nechayev quite freely journeyed to Switzerland and surfaced in March 1869, welcomed with open arms by Mikhail Bakunin, the Anarchist doyen and idol of many Russian revolutionaries, with his thrilling life, through the fires of Europe in 1848, imprisonment in Russia and exile in Siberia, his daring escape to Japan in 1861, his travel to the U.S., and return to Europe, preaching unrelenting rebellion against every sacred cow of polite bourgeois society and fighting against Karl Marx for control of the First International (1868-76). To Nechayev, however, Bakunin was a mark. Bakunin’s globe-trotting, and his deep internationalism that attached no more significance to Russia than anywhere else, left him seriously uninformed about—and largely uninterested in—his native land.11

It made it easy for Nechayev to convince Bakunin that there was a secret, centralised organisation in Russia poisoned for revolution, and to get Bakunin to jointly sign a series of manifestos and proclamations in service of this non-existent organisation. (Nobody else was fooled: not a single person applied to join when recruits were publicly called for.) What Nechayev had was Bakunin’s fanatical devotion to revolution. The fact that Bakunin’s notions of a spontaneous revolution led by brigands leading to a Stateless Anarchist Utopia bordered on childish was an asset to Nechayev—as was the fact that, while Bakunin remained a symbol for the revolutionaries, he never had serious ideological influence. There were no converts to persuade of a new way; there was simply Bakunin’s platform and name to build up Nechayev’s reputation and be used to get Nechayev’s ideas out.12

Nechayevism in Theory

It was in Geneva, between April and August 1869, that Nechayev wrote the most famous nineteenth-century Russian revolutionary manifesto, The Revolutionary Catechism,13 which Bakunin had contributed to.

The Revolutionary Catechism describes the revolutionary as a “doomed man”, with no interests, feelings, or property—“not even a name”. He has a “single thought, one single passion: the revolution”. To that end, the revolutionary becomes a “merciless enemy” of society, maintaining ties with it only insofar as it helps him “destroy it the more surely”. “He despises public opinion”, the Catechism says, specifically all conventional morality and the laws flowing from it. “Morality for him is everything that contributes to the triumph of the revolution. Immoral and criminal is everything that hinders it.” Revolutionaries must be ready to die and set aside all gentleness and sentimentality—friends, family, romance, even a sense honour. The revolutionary must be ruthless with himself and with others, but not for personal reasons: all must be subordinated within him to the “cold passion of the revolutionary cause”. Nechayev underlines: “Day and night he must have one thought, one goal—merciless destruction.” There is to be no friendship even within the revolutionary cadre. The fully initiated leadership core act in concert, Nechayev wrote, but the second- and third-degree circles of the revolutionary organisation are to be treated as “common revolutionary capital” at the disposal of the leaders: used wisely, yes, but without consideration for the individual humans. A comrades’ worth “is determined solely by the degree of his practical usefulness in the cause of all-destructive revolution”.

Nechayev called in the Catechism for the revolutionaries to infiltrate all sectors of society—business, bureaucracy, middle class, Russian Orthodox Church, the Third Section (secret police), and even the Tsar’s Winter Palace if possible. High officials are to be immediately exterminated, except those whose continued misdeeds will anger the people and push them towards revolution. Lesser nobles are to be blackmailed to assist and finance the revolution; lower officials and the liberals are to be exploited by pretending to their friendship until they are so compromised they can be used to “foment turmoil in the State”; other revolutionary conspirators outside Nechayev’s group were to be similarly manipulated; and women were to be used in every way: extorted where they were not signed-up revolutionaries, and female true believers used effectively as prostitutes to ensnare noblemen and liberals.

As for “the people”, their “complete liberation and happiness” was, of course, the purpose of the revolution, Nechayev wrote, but since “an all-destructive popular revolution” was the only means to that end, the immediate task was to put all the revolutionaries’ resources toward “the intensification and spread of the people’s miseries and evils until their patience is exhausted and they are impelled to a mass revolt”. Ideas—i.e., their own dream world—always took precedence over human beings for the terrorist-revolutionaries. “The worse, the better” would become the revolutionaries’ slogan, and the Nechayevist impress there is obvious.

Forging an “unconquerable, all-destructive force—this is [the purpose of] our entire organisation, conspiracy, and task”, Nechayev went on, saying, in a notion clearly drawn from Bakunin, that the most immediate ally the revolutionaries must enlist to this end is the “daring brigand world” of outlaws. Nechayev rejected any responsibility for formulating a vision of the post-revolutionary government: the revolutionary conspirators’ job was “fervent, total, universal, and merciless destruction”, since “the only salvation for the people is a revolution that destroys every kind of statehood down to its roots, exterminating all State traditions, orders, and classes in Russia”.

By the first years of the 1870s, “Nechayevism” was already recognised as a category, the only revolutionary current before “Leninism” to be named for an individual, with the partial exception of “Bakuninism”. The lexicography around, never mind the sources for, Nechayev’s ideology could be an essay of its own. Nevertheless, some brief points can be made.

The very name of Nechayev’s manifesto—a “catechism”—points to the Christian heritage Nechayev is drawing on, and the whole format of the brief document is a code of conduct for a monk-like cast of revolutionaries that synthesises the ideas of the intelligentsia developed in the twenty years since Chernyshevsky, presenting them without euphemism. That Nechayev’s goal was the destruction of a Christian society, and his description of the methods to get there was written in terms designed to frighten off anyone with a shred of Christian morality remaining to them, is only to reiterate the paradox of the French Revolution, the “Christian event par excellence”,14 and later of the Soviet Union,15 which unleashed Terror on the pillars of Christian civilisation, the Church included, in pursuit of the Christian mission that “the last shall be first, and the first last”.16

The word indissolubly linked to Nechayev’s name is Nihilism, and it is not unreasonable. “Nihilism” originated in the early 1860s as a term of criticism for the younger revolutionaries, the Generation of the Sons, and Nechayev was unquestionably one of the intended targets.17 Moreover, there was a doctrinal Nihilism, developed by Pisarev and popularised by the more simplistic Varfolomey Zaytsev, which Nechayev certainly embodied with his call to engage in the world only to more speedily destroy it and his demand that the true revolutionary “must hate everything and everyone equally”.18 However, Nihilism—even in the more developed, Pisarevian sense—was never a distinct or separate phenomenon in the Russian revolutionary context; it was a moral outlook derived from Chernyshevsky’s uncompromising utilitarian vision of the ends justifying the means, and as such was shared widely across the revolutionary spectrum.

Another descriptor for Nechayev is Jacobin: his debt to that tradition is self-evident in the Catechism, and it probably best-describes his broad alignment in the contemporary factional landscape of the terrorist-revolutionaries. Simply calling Nechayev a Narodnik is fraught since his conscious program was to reshape and redirect mainstream Narodism;19 the difficulty is that he was so successful, thus to speak of the Narodniks after Nechayev is to be speaking about Nechayevshchina at some level.

For the sake of completeness, it should be added that Nechayev was not an Anarchist. Claim otherwise, which still show up in academic works, are based largely on Nechayev’s association with Bakunin, and often use in evidence polemics of the period, particularly from Marx and his disciples, whose ignorance of Russian dynamics was as complete as their hatred for Bakunin and anybody they viewed as associated with him.20

Nechayevism in Practice

Nechayev returned to Russia in early September 1869,21 bringing with him a membership card for the fictional “World Revolutionary Union” signed by Bakunin; a rubber stamp in the name of “the Russian Section” of the alleged Union, Narodnaya Rasprava (“The People’s Retribution” or “The People’s Summary Justice”); a large amount of money taken from the nearly-dead Herzen under the false pretences that Nechayev would use it to make Narodnaya Rasprava into a reality; and a copy of the Catechism.22

Not quite 22-years-old, Nechayev set himself up in Moscow and presented himself as leader of the local branch of the non-existent international Union, which he claimed had four million men ready to strike simultaneously upon the given signal against every monarchy in Europe. (Note the similarity to the Ishutin Society, which was explicitly cited in the first issue of Narodnaya Rasprava’s journal as having “taken the initiative” that had to be capitalised upon.23) Nechayev recruited about eighty students in Moscow, mostly from the Agricultural Academy and Technological Institute, into a tight-knit, conspiratorial group entirely under his spell.24 There are signs Nechayev’s group was spreading: Nechayev’s most able deputy, Ivan Gavrilovich Pryzhov, had an easy way with “the people” in several surrounding towns thanks to his own peasant background; Nechayev spent time in Ivanovo; and there seem to have been recruits among the workmen at a munitions factory in Tula.25 Nechayev set the date for revolution on 19 February 1870, the ninth anniversary of the serfs’ emancipation. There was to be no revolution, not even a minor armed rising, and Nechayev’s whole “career” as an operational revolutionary lasted just three months—but its impact can hardly be overstated.

Nechayev in these months in Moscow, September-December 1869, cut a formidable figure: “feared and adored, mysterious and omnipotent”, as Szamuely describes him, and yet “Nechayevism” in practice was rather underwhelming. Nechayev spent most of this time trying to bring State repression on the students, his own members and others, by getting them expelled from university and imprisoned. As with his plans for “the people”, Nechayev’s operating thesis was that this would consolidate the student body into a revolutionary mass. Nechayev also took rival revolutionaries, such as Mark Natanson, off the board by planting seditious manifestos on them and then tipping-off the police. In the early morning of 21 November 1869, acting under Nechayev’s incitement, one of the revolutionary students, Ivan Ivanovich Ivanov, was beaten and shot to death, then thrown through the ice into a lake. Nechayev had told his comrades that Ivanov was a traitor; perhaps he believed it, but there is a strong suggestion the luckless Ivanov had made the mistake of beginning to question the leader.26 Either way, Nechayev was pleased to have the chance to bind—that is, trap—his group together by staining them with blood,27 a lesson that would live long after him among the revolutionaries. Police soon discovered Ivanov’s body and correctly concluded it was a political murder, arresting Nechayev’s group and a wider circle of sympathisers and collaborators. Nechayev himself fled, first to Petersburg at the end of November and then abroad in mid-December 1869, to London and Paris, before settling back in Switzerland.28

Nechayev was not quite finished yet. Nechayev reconnected with Bakunin, who remained entirely bewitched by the young man. Nechayev now used his status as a dare-devil hero of revolution, and the legend of his underground group inside Russia, to make a bid for the leadership of the émigré community. Bakunin did not mind—the principles Nechayev preached were joint principles, after all. As part of his campaign to bring down the Tsardom from the without, Nechayev published two intriguingly anomalous manifestos that appealed to the nobles to save themselves from the imminent peasant revolution by pre-emptively deposing the Tsar. More usual were appeals to students. Nechayev’s writings about his post-revolutionary vision in this period are interesting for showing signs his outlook was internationalising, increasingly incorporating Marxist elements, and the heavy tread of Russian Jacobinism, looking back to Pyotr Zaichnevsky’s “Young Russia” and expressing ideas Tkachov would soon flesh out—a foreshadowing of the road the Russian revolutionaries would take to victory in 1917.29

Bakunin could hardly have been more cooperative, but Nechayev wanted, as always, total control, and rifled through Bakunin’s papers to find material that would discredit and endanger the old man. Bakunin submitted to this blackmail for a few months, before finally breaking all ties with Nechayev in the summer of 1870.30 It was darkly funny that Bakunin, that devotee of destruction, who had gushed, “They are magnificent, these young fanatics, believers without God”,31 would write a few weeks later, on 24 July 1870, to his friend Alfred Talandier, in anguished and indignant tones about what this “pitiless” and “dangerous fanatic” had done to him (though, in fairness, even here Bakunin could not suppress his confused awe at Nechayev’s selfless dedication, his “life of a martyr”). For all of Bakunin’s posturing, he was a son of the nobility who dealt decently in personal relations. Bakunin might have put his name to the blood-curdling calls for violence Nechayev drew up, advocating a revolutionary Machiavellianism of deceit and the trampling of all conventional (Christian) morals even within the revolutionary cadre, but Bakunin was absolutely bewildered in dealing with someone who actually believed it.32 Nechayev subsequently gravitated towards Nikolay Ogarev, the old friend of Herzen.33

When Nechayev was arrested in Zurich in August 1872, in an operation orchestrated by the Russian Third Section,34 Bakunin swallowed his pride and joined the campaign against Nechayev’s extradition to Russia. The campaign failed: Nechayev was returned to Russia in October 1872 and was found guilty of murder in January 1873 by a jury in a brief trial that lived up to the hype of Nechayev’s reputation: the terrorist refused to recognise the court’s legitimacy, repeatedly obstructed proceedings, and had to be dragged from the courtroom—while shouting, “I am no longer a slave of your tyrant!”—after he was sentenced to twenty years hard labour and a life of exile in Siberia. Taking no chances, the Russian government simply “disappeared” Nechayev, scrubbing his name—from now on he was known as “Prisoner Number Five”—and putting him in the Alexei Ravelin of the Peter and Paul Fortress with no access to the outside world. It was mandated that Nechayev not even receive letters. But he did receive them, and that was the least of it. This concluding chapter of Nechayev’s life was perhaps the most extraordinary, and it certainly cemented his legend.

In January 1881, the Executive Committee of Narodnaya Volya, a Nechayevist terrorist group established in 1879, read a letter at one of its meetings from Nechayev, where he blessed their mission and called for them to secure his release, enclosing a detailed practical plan. It was as if they had seen a ghost. For the Men of the Seventies, Nechayev was a half-forgotten fable, and now here he was, his revolutionary zeal undimmed by eight years in the most formidable maximum-security dungeon in the country. Ultimately, the Narodovoltsy decided against an immediate move to spring Nechayev since they were concentrating on murdering the Emperor. Nechayev, true as ever to his own principles, accepted this without rancour as a wise use of revolutionary resources, and set himself to assisting their enterprise. This he was able to do because Nechayev had recruited practically the entire staff at the Ravelin; this was how he had set up a communications channel with the Narodovoltsy in the first place. It is a feat perhaps unique in all of history. None of the staff knew the others had been recruited; all spied on each other and reported to Nechayev. It is an extraordinary testament to Nechayev’s personal magnetism that he achieved this without a single assistant and without even the use of his name.35

The plans for the Narodovoltsy to break Nechayev out collapsed after they succeeded in assassinating Tsar-Liberator Alexander II in March 1881, and Nechayev’s efforts to get the guards themselves to release him were terminated in November 1881 when, probably because of a report by the one other prisoner in the Ravelin, the Imperial Government discovered that it had lost control of its premier prison. The guards Nechayev had suborned were removed—at their trials they uttered not one word of condemnation for the man they referred to only as “he”—and the new guards moved Nechayev into total isolation. Placed on very basic rations and kept in the dark, Nechayev died on 21 November 1882, six weeks after his thirty-fifth birthday and the thirteenth anniversary of the date he had murdered Ivanov.36

Nechayev’s Legacy

Though the charge of “Nechayevism” would become a staple term of condemnation in the polemics of the fractious Russian revolutionary movement, it would be a mistake to interpret this as a substantive rejection of Nechayevism. For one thing, on the subject of Nechayev personally, a determined ambivalence set in for the intelligentsia. The details faded; all that was left was Nechayev’s hypnotic, mysterious personality, and self-sacrificing devotion. It was conceded some of Nechayev’s methods had been dubious—the Ivanov murder stood out as a black mark—but, in a pattern that was to repeat, the general sense was that these were excesses in practice that did not detract from the nobility of Nechayev’s intent in theory. What the intelligentsia could not get around was that Nechayev had made operational the ideas of Chernyshevsky; built on the tradition of Pisarev, Zaichnevsky, and Ishutin; and that all that Nechayev had done was for the Cause.37 Speaking ill of Nechayev in revolutionary circles could cause consternation sufficient to raise the spectre of fist-fights even a quarter-century after his death.38

The ideological potency of Nechayevism, combined with the pragmatic fact that Nechayev had seriously thought through insurgent warfare in a Russian context, meant that as violence came to define the revolutionary movement in its last forty years the Nechayevist ethos gained ground and was dominant among the terrorist-revolutionaries by the turn of the twentieth century, if not before.39

Still, the only group that, for a time, acknowledged Nechayev as a predecessor was the one that mattered most: the Bolsheviks. As late as 1924, the official History of the Russian Revolutionary Movement by Mikhail Pokrovsky pointed to Nechayev as providing the “essence” of the Bolsheviks’ conspiratorial structure and the blueprint for their violent seizure of power.40 Vladimir Lenin, the Bolshevik leader, was an admirer of Nechayev’s, and one of the Lenin’s first major acts in power was taking the Nechayevian decision to massacre the Royal Family in no small measure to trap wavering Bolsheviks into remaining loyal to him.41 In time, as happens in so many successful religious movements, the origin myth of Bolshevism was re-written. The canonical story told of a clean apostolic succession from Marx, and since Marx had virulently attacked Nechayev (as part of Marx’s campaign against Bakunin) it meant Nechayev had to be purged. Nechayev was steadily written out of Bolshevik genealogy under Stalin and fully excised during Yezhovshchina in the 1930s, where he was condemned, like all the other victims, with hysterical lies of a kind the Tsardom had never contemplated.42

Pokrovsky’s memory fell with Nechayev’s, but he would be rehabilitated after Stalin’s death. Even Trotsky was rehabilitated, albeit after the demise of the Soviet Union. Nechayev alone among the architects of the Bolshevik Revolution remains officially buried. The remarkable aspect of this is that the retrospective Soviet repudiation of Nechayev has basically been taken at face value by Western scholars: it took decades for any dissent to appear, and to this day the academic consensus minimises the Bolshevik inheritance from Nechayev.

GOING TO THE PEOPLE: THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTIONARIES’ ONE BREAK FROM TERRORISM

The trial of the “Nechayevites” in 1871, the first of a series of political trials designed to discredit the revolutionary movement, became an international spectacle. The Russian government succeeded in showing the terrorists’ wickedness in design—printing The Revolutionary Catechism in full in the Official Gazette—and haplessness in execution. Despite the incensed public mood, the Russian security services and courts did a creditable job sifting the guilty from the innocent: of three-hundred arrested, only eighty-five were charged; fifty-one were acquitted, and thirty-four sentenced. There was a coda to this: the head of the Third Section since the Karakozov affair, Count Pyotr Shuvalov, forceful liberal though he was, saw the judicial verdict as grossly inadequate for the security of the State and used his administrative powers to send most of the acquitted to Siberia. Even here, however, there were signs of the new ways: this was reported in the press and Shuvalov bitterly criticised.43

Literature continued as a theatre where much of Russia’s public politics were played out and the serialisation of Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novel Demons (or The Possessed) in 1871-72 caused a sensation. I.I. Ivanov had been a friend of Dostoyevsky, once helping the great novelist make a trip to Europe, and Dostoyevsky became consumed with the case.44 Dostoyevsky had once been close to the radical intelligentsia, connected to Nikolai Nekrasov and Vissarion Belinsky around the time he published his first novel, Poor Folk (1845), and he was a member of the Petrashevskists when they were broken up in 1849, after which he spent five years in Siberia. This experience in Dostoyevsky’s early-thirties profoundly changed his political outlook, shifting him from universalist socialism to a Slavophile Orthodox Christianity.

Demons was Dostoyevsky’s most potent judgment on his former comrades, and it was devastating. Nechayev appears as “Pyotr Verkhovensky”, and minimal artistic license was needed or taken in presenting his activities and beliefs. It was Dostoyevsky’s novelistic portrait that solidified Nechayev’s dark reputation in the popular imagination well beyond Russia, at the time and since. In this moment when even the radicals in Russia were trying to “distance” themselves from Nechayevist horrors put on public display in court, there was little attempt to defend Nechayev. What truly aroused fury was Dostoyevsky’s central premise: that Nechayev was an authentic product of the intelligentsia, which was rotten to the core in its yearning for catastrophe. Bad enough that Dostoyevsky said this of the Chernyshevsky-adoring youth of the Sixties; more wounding that he laid Nechayev at the door of the “out-of-date liberals”,45 the Men of the Forties, the Fathers of the intelligentsia, who had by now already been devoured by their Sons. The cut was deep because they knew it was true—the recently-departed Herzen had written as much—and that there was nothing they could do about it: the monster they had created was now out of their control.

The Revolutionaries Test Non-Violence

As happened after Karakozov’s attempt on the Tsar in 1866, the shock of Nechayev did temporarily induce changes in the intelligentsia: without any alteration in their ideology, they reacted against the Men of the Sixties by deciding conspiracy by a centralised organisation led in a toxic direction and “politics” was a dead-end; they fell back on the more orthodox Narodist idea that “social” revolution was the path. This outlook was reinforced by the suppression of the Paris Commune in May 1871 after just two months.46 In going back to the drawing board, the intelligentsia alighted on Pyotr Lavrov (1823-1900), a scholarly figure with a liberal streak on the Herzen model, who had been caught up in the dragnet in 1866 and then moved to Paris in 1870.

As ever, the herd of independent minds that was the intelligentsia changed course with startling rapidity and uniformity; disillusioned with one set of ideas that had the answers to all their problems, they fell to the next. Lavrov’s basic idea was that the intelligentsia needed to acknowledge that its privileges rested on the sacrifices made by the lower orders, meaning they had a moral duty to repay these debts, with the reparations taking the form of, first, educating themselves, then bringing this betterment and enlightenment to the people and guiding them to revolution. The time of derring-do Jacobin conspiracies and bloodshed was over; the time of “self-education circles” and “propaganda” (a then-new word) to transmit this knowledge to the masses was all the rage. The authorities were pleasantly surprised that the throngs of “eternal students” were undertaking something approximating academic study and made no effort to inhibit their work, such as setting up networks of student libraries. The groups that formed, most prominently the “Tchaikovskist circle”, created by Natanson and named for its most influential member, Nikolai Tchaikovsky, would prove to be incubators of the “professional revolutionaries” that appeared later in the decade, but at this time they were loosely organised and formally leaderless, a deliberate repudiation of Nechayevist iron discipline.47

Lavrov’s articles for Historical Letters, published in Petersburg in 1868 and compiled into a book in 1870, was now the intelligentsia’s bible, received with an enthusiasm not seen since Chernyshevsky’s What is To Be Done? A lot of historiography presents this period as one of pure idealism and moral uprightness, and it is true that Lavrov emphasised ethics—hence his sustained attacks on Pisarev and Nechayev (without naming them). But when examined, there was a lot less difference than met the eye. The Tchaikovskist circle was quite happy to fund itself by having a young girl, Pisarev’s sister no less, prostitute herself to an old man; she killed herself soon after. Liberalism and constitutionalism were still utterly rejected by Lavrov; the ends still justified the means; deception and wholesale violence against “enemies” were still licit in service of the Cause.48

Lavrov’s focus on the social dimension echoed classical Narodist doctrine back to Herzen and Chernyshevsky, but his substantive vision for a Stateless post-revolutionary Russia had more in common with Bakunin. Lavrov’s methods for revolution starkly opposed Bakunin, though. Lavrov insisted that the revolution had to be by the people. There was no more talk of a minority, however enlightened, moving events; revolution from above in any format was off the table. Revolutions could not made by small groups of conspirators, Lavrov preached: revolutions were the culmination of vast historical processes, in Russia’s case based on the holy obshchina (village community), where the intelligentsia believed Russian peasants lived in a natural state of socialism, and had to be undertaken by the majority. All the intelligentsia could do was prepare for the revolution and hasten the day by painstaking work among “the people” to make them understand that their happiness lay in destroying the existing system and building a socialist order on its ruins.49

The upshot of all this was one of the most extraordinary, bizarre, and, frankly, hilarious, episodes in the history of the Russian revolutionary movement. Preparations for “Going to the People”,50 as Lavrov had instructed (building on earlier—ignored—ideas by Herzen and Bakunin), were made in late 1873: university students began forming relationships with factory workers, learning trades like carpentry, and armies of revolutionary missionaries prepared to head into the towns and villages. The only description of this quixotic campaign is “religious”. Equipped with faith in the Russian peasants as nature’s socialists, in the early spring of 1874, thousands of selfless and self-motivated students poured out of the twin capitals to proselytise on a scale and with a zeal not seen since the Raskol (Schism) in the Russian Orthodox Church and the bringing of Christianity to Siberia in the seventeenth century. Yet the lack of central organisation, the very thing that made “Going to the People” so remarkable, meant there was no ideological or strategic uniformity. The students tried to dress and speak as peasants, and to share in their hardships as a form of atonement; some thought it through no further. Many students vaguely imagined they could gain the peasants’ trust and mobilise their latent socialism into a spontaneous mass-revolt, though how or when was disputed.51

“The Mad Summer of 1874” did not last long: within weeks, the revolutionaries were hit with the shattering revelation that, after three decades of discussing “the people” they idolised from every angle, they both knew nothing about the Russian masses as they actually were, and were wholly unable to reach them. A “Going to the People” lecture in a Ukrainian village, using Britain’s experience with enclosures as a scare story about constitutionalism, with its property rights, among other things, enraptured the peasants—but it did not worry them. To the peasants, the story showed the danger of powerful lords, and they had a Tsar who kept the nobles in line. Osip Aptekman, a revolutionary who lived to see the Bolshevik coup, watched in utter bewilderment as his subversive gathering turned into a lively discussion of the benefits of autocracy. Regicide was at best incomprehensible; the peasants found it easier to understand a Tsar without Russia than Russia without a Tsar. When the peasants did grasp what was being said, it provoked active hostility. Some dedicated students tried to persist into the autumn of 1874, and there was a second To-the-People effort in 1875, but by then hundreds of the revolutionary activists were in prison, handed over to the police by the peasants, quite often after being beaten up for their seditious ideas about replacing the Tsar-Liberator, a moral blasphemy to the peasantry and an idea they darkly suspected was rooted in an attempt by these interloping social betters (barin or “masters”) to return them to serfdom.52

The Fall of Pyotr Lavrov and Revolutionary Faith in “the People”

The fiasco of “Going to the People” sealed Lavrov’s fate. “Apart from Herzen, [Lavrov] was probably the only important Russian radical ideologist whose ideas bore even a limited resemblance to Western concepts of liberalism and democracy”, says Szamuely, which perhaps explains “why they left no lasting imprint on the Russian revolutionary movement”.53 The practical catastrophe of “Going to the People”, the imprisonment of hundreds of comrades, was matched by the embarrassment, an emotion that easily became rage, and the ideological shock. The rage was turned on Lavrov. Lavrov, while not suffering quite the same level of personal abuse as Herzen, was if anything more completely excommunicated. Sergey Kravchinsky (“Stepniak”), a proficient “practical worker” of the Narodniks who would in 1878 assassinate the head of Russia’s Gendarmes, General Nikolai Mezentsov, wrote to Lavrov in early 1876, “You are a man of reason, not of passion … that is insufficient”.54 But the effect went deeper than one man’s ideas.

Not only had Lavrov’s concept of gradualist, popular revolution broken upon the rocks of reality; it had taken the intelligentsia’s belief in a mystical connection with “the people” down with it. The warning signs after the Karakozov affair that the intelligentsia was radically disconnected from “the people” could no longer be ignored. “Yet another break with the past was inevitable”, Szamuely notes. The revolutionaries concluded firmly and finally that revolution by the people was impossible: the peasants were not at a level of “development” or “consciousness” for this to happen, and no amount of socialist propaganda would make them so. Waiting on a mythical all-Russian rebellion would be the death of the revolutionary movement, with capitalist development proceeding so quickly and constitutionalism on the horizon. Revolution had to be made by a “small group [in] a small place”, as Kravchinsky put it. The need for an elite organisation and the urgency of revolution to derail capitalist-constitutionalist development: these were the conclusions drawn from the To-the-People experiment.55

Lavrov’s following was drastically reduced after 1874, but “Lavrovism” did not die immediately. Lavrov would continue to argue his case for half-a-decade. Unfortunately for Lavrov, his attempts to modify his doctrines to take account of the failures during “Going to the People” only underlined how unrealistic his program was. By the end of the 1870s, Lavrov was completely discredited. Lavrov would be drawn into a debate on revolutionary fundamentals that set out in the clearest terms the dividing lines in the revolutionary movement. All debates afterwards were variants on this great set-piece. Lavrov’s antagonist was Pyotr Tkachov, a name virtually unknown outside Russia.56

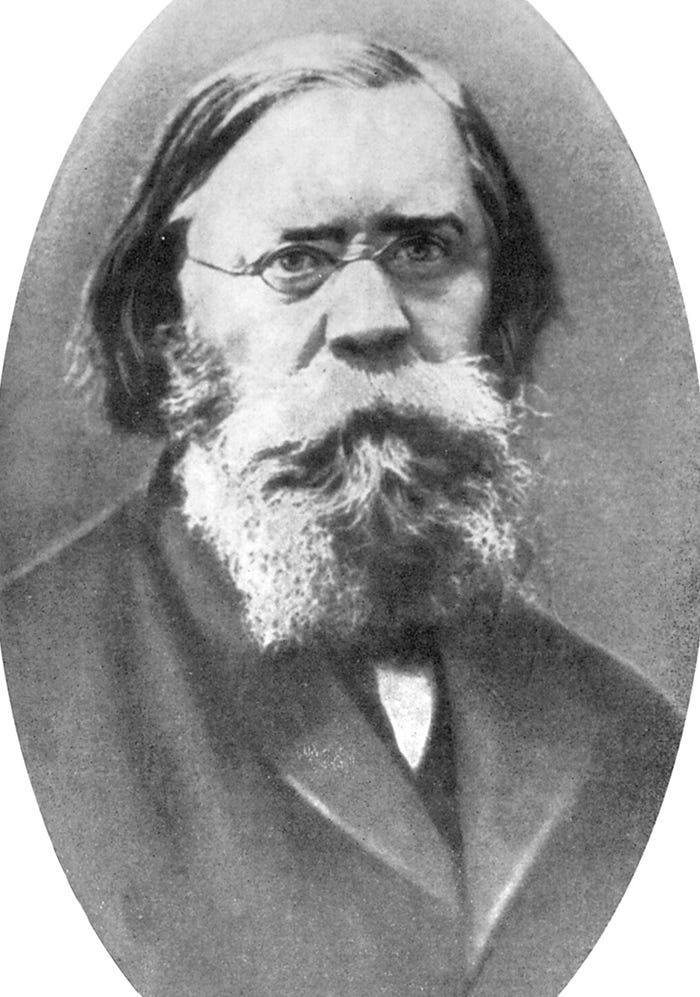

THE UNHERALDED ARCHITECT OF TERRORIST REVOLUTION: PYOTR TKACHOV

Tkachov, born to a petty noble family in 1844, joined the revolutionaries early: he was first arrested during the student strike in 1861. As a self-described Jacobin, Tkachov spent the 1860s outside the ideological mainstream and very much within the operational mainstream, alternating between journalism and jail. The turning point that launched Tkachov to prominence was his association with Nechayev: the two wrote the Program of Revolutionary Action and were close, though Tkachov, always “cold and rational”, writes Szamuely, “never seems to have fallen under [Nechayev’s] hypnotic spell”. Tkachov had been arrested in March 1869 and tried with the other “Nechayevites” in 1871, though he was not accused of complicity in Ivanov’s murder and was released sixteen months later. Unlike many others, Tkachov never wavered in his commitment to “Nechayevism”.57

In December 1873, Tkachov went into self-imposed exile, smuggled to Switzerland by the Tchaikovskists. Very briefly, Tkachov collaborated with Lavrov at Vperyod (Forward), publishing one article. Tkachov’s ideology had been formed before he left Russia and he had long been suspicious of Lavrov. Familiarity bred contempt: Tkachov came to see Lavrov as poisoning Russia’s youth with liberalism, which could only retard the progress of the revolution. Tkachov fell in with the Cercle Slave, a small, Jacobin-inclined Russo-Polish group in Zurich that disliked Lavrov and Bakunin equally, and it was probably with their financial assistance that, in April 1874, Tkachov published The Tasks of Revolutionary Propaganda in Russia, a full-scale denunciation of Lavrov, the opening shot in a six-year debate that split the revolutionary movement and which Tkachov ultimately won—decisively.58

Revolutionary Synthesis

Some studies of Tkachov take his lifelong self-description of “Jacobin” at face value, or lump him in with the “Blanquists”,59 and others describe Tkachov as “the first Russian Marxist”. What Szamuely convincingly argues is that all of these categorisations are superficial: what made Tkachov so innovative an ideologist was his blending together of Jacobinism, orthodox Narodism, and Marxism, a trendsetter for what was to come.

Tkachov took absolutely for granted the classical Narodist precepts, expressed from Herzen onwards, of Russia’s special advantages in building socialism—the obshchina as the nucleus and the country’s backwardness providing a blanker slate for the leap from village socialism to national socialism, without the thickets of legal-political tradition in Latin Europe—and that a revolution was imminent (or, more precisely as we shall see, could be) since “the people” were primed with a yearning to destroy the present order. Where Tkachov departed from the Narodniks was in his view that Russia’s advantages were not eternal facts, but a fluke of history. It is here that the Marxism comes in.60

The misperceptions about Tkachov and Marxism result from the fact that Tkachov was the first serious Russian student of Marx’s work—the first, indeed, to mention one of Marx’s books (The Critique of Political Economy) in Russian, in 1865. Tkachov saw Pisarev’s materialism as “vulgar”, while regarding Marx’s economic materialism as sophisticated and scientific. The key ideological consequence of this was Tkachov contending that Russia was unexceptional in its historical development: having proceeded on Western European lines toward capitalism, it would go all the way. Russia was catching up with the West quickly, in Tkachov’s estimation. Soon there would be a bourgeoisie, a social layer to root and protect a State that at present hovered precariously above society, and village life was already dissolving, with peasants heading for industrial work in the cities and those who remained being stratified by the spreading wealth in rural areas. Tkachov and Marx were united on this reading of events, which Narodism rejected, seeing Russia as unique and implicitly believing the obshchina had mystical regenerative capacities. The difference was Marx approved of this trajectory and Tkachov held to the orthodox Narodist view that this was the ultimate nightmare. Tkachov believed—and was the first to argue—that Russia was an exception to Marx’s theories that capitalist development was necessary before revolution. Revolution was an immediate necessity for Tkachov to prevent the industrial and inevitable constitutional development of Russia that would soon whittle away the obshchina on which he, like all Narodniks, rested so much of his revolutionary hopes for Russia.61

The method for Tkachov’s revolution—a tight-knit conspiratorial organisation seizing State power—was provided by Zaichnevsky, Nechayev, and the other Jacobins. Tkachov’s only criticism of Nechayev was the slipshod security and ineffectiveness of his konspiratsiya (tradecraft). But this is only half the story and leaving out the other half is what causes the confusion with Blanquism. The Blanquists believed in a minority revolt, i.e. a coup d’état isolated from the masses, posited in opposition to the Bakuninist notion of a spontaneous mass-peasant rebellion. Tkachov in effect combined the two. Tkachov’s concept was a minority-led revolution. Tkachov firmly believed that a revolutionary Übermensch, superior in education and morals, must be the active force in planning and execution, but he was equally firm that the masses should be mobilised—manipulated, if need be—into providing the numbers and power for the revolution to overwhelm the State. This is what would later be called “vanguardism” and is the reason Tkachov is sometimes called “the first Bolshevik”.62

This ideological fusion of Tkachov’s was potent and durable. Tkachov would not get much credit for it—second to Nechayev, he was among his contemporary comrades and has been in the historiography ever since the most controversial figure in the Russian revolutionary tradition. But Tkachov’s influence can be demonstrated by the impact of two of his fundamental insights.

The first is Tkachov’s argument that among the reasons Russia was better primed for revolution than Latin Europe was the weakness of the Tsardom. In the West, even large numbers of insurgents, whether it was 1848 on the Continent or the Irish eruptions against the British, had a hopeless task, let alone small numbers of revolutionaries, because the State—here Tkachov drew on Marx—was an expression of social forces and class interests; even the police and the army were woven into the fabric of society. The reverse was true in Russia. The State-above-society nature of Russia—the fact that everyone, from high officials to the clergy and business leaders depended upon the Emperor for their position—made the Russian State uniquely vulnerable. The state, “so to speak, hangs in the air”, as Tkachov put it. That the apparently mighty Russian State could be disrupted in a way no Western State could be by a relatively tiny number of well-organised terrorists was an insight successive generations of revolutionaries held on to.63

The second major way Tkachov shaped the revolutionary tradition was his view of the role of “the people” in the revolution, which was the central division among Russian revolutionaries—a far more accurate dividing line for categorisation than attempts which focus on “extremists” and “moderates”, methods and tactics, or ideology per se, since they all shared a “common framework of ideas”.64 Unlike mainstream Narodism, Tkachov had limitless contempt for “the people” as an active participant in the revolution.

Tkachov lambasted the widespread Narodist ideas of “popular genius” (that “the people” knew better than the revolutionaries) and “popular self-education” (that “the people” would or could “get wiser”, i.e., become revolutionaries). Popular discontent could be a resource in the revolution if stoked and harnessed properly, through emotional appeals since revolutionary “consciousness” was very low among “the people”, Tkachov argued, with the corollary that most Russians were so accustomed to obedience they would only join the revolutionaries after the government was defeated, and even then this would most likely be expressed in an initial spasm of destructiveness before they lapsed back into customary ways.65 Tkachov making this argument when Lavrov was at the height of his influence, as thousands of Russian students were fanning out across the Empire to inculcate socialism in “the people”, ensured it was all the more effective: as the intelligentsia rebounded from its disillusionment when Lavrov’s ideas failed, Tkachov’s prophetic utterances were right there, corresponding to a reality they had experienced at first hand and offering them the new answers.

Tkachov’s view of the peasantry as an inert mass, some of which could be induced to participate in revolution by a combination of a conspiratorial revolutionary elite, Lavrov’s propaganda (or missionary) work, and agitation (or incitement),66 was vindicated in the Chigirin district near Kiev in 1876-77, when a group of Narodniks directed by Iakov Stefanovich managed to draw about one-thousand peasants into a conspiracy by handing out a fabricated “Secret Imperial Charter”, signed by the Tsar and dated February 1875, purportedly calling on the peasantry to form “Secret Militias” and rise in rebellion to overthrow the nobility who had frustrated the full implementation of the Emancipation Decree. This was (as they could not know at the time) the one success the Narodniks ever had in organising the peasantry, and it was based on the tradition of blatant deception dating back to the Decembrists and developed through Ishutin and (the supposedly reviled) Nechayev. The only complaint raised by some of the intelligentsia was that it had dissipated resources and got a number of revolutionaries arrested. The deportation of one-hundred illiterate peasants to Siberia did not register with the intelligentsia. Most enduringly, the Chigirin affair was seen as proof-of-concept for elite conspiracies.67

The further implication of Tkachov seeing the people as incapable of liberating themselves—of not even knowing that they needed to be liberated—was that the revolutionary minority that executed the revolution would retain power afterwards. Tkachov understood that the peasants were conservative by nature and if power was shifted into their hands the last thing they would do is build socialism. The revolutionary minority, controlling the State, would have to impose socialism. It was at this point—once the revolutionaries were in power, not before, as Lavrov believed—that Tkachov saw propaganda having an important role in reshaping the masses. But Tkachov was not so naïve, nor so dishonest, that he claimed re-education would be enough.68

The violence inherent in this system was not obfuscated: Tkachov, logical as ever, accepted and advocated it. It was explained that this Terror was for “the people’s” own good—just as a revolution from above in the interests of the people was entirely different to one for bourgeois interests. In contrast to much of the Western historiography down to the present day, which portrays the Tsardom as a quasi-totalitarian, Tkachov, a man who lived under it and “suffered” at its hands, criticised the Imperial Government for its softness and scrupulosity; under his regime, the space and favourable conditions given to State opponents, the legalistic precision and procrastination, would all be done away with to “swiftly and irrecoverably” eliminate enemies.69

Russia had heard arguments for a minoritarian revolutionary dictatorship, from the Decembrist leader Pavel Pestel, who imbibed the ideas at source from the French Jacobins, and from his heirs like Zaichnevsky, but never as forthrightly as this.

The Great Debates

Lavrov might have thought of Tkachov as an upstart schemer, but Lavrov was perceptive enough, even at the pinnacle of his influence, to understand that a Russian revolutionary movement that had stampeded so quickly and unanimously in his direction could stampede away from him just as easily. Lavrov’s response to Tasks was immediate and comprehensive. In To the Russian Social-Revolutionary Youth in 1874, Lavrov directly accused Tkachov of reviving the dreaded spectre of “Nechayevism”, attacked Tkachov’s central thesis by supporting the Marxist line that capitalist development would not impede socialist revolution, and rejected with great force the notion of minoritarian dictatorship.70 This response bought Lavrov only a few months. In November 1875, Tkachov started a journal, Nabat or “The Tocsin, the allusion being to the need for an immediate call to action as time was slipping away. Though it was never quite as successful as Herzen’s Kolokol, Nabat emerged in the context of the post-To-the-People despondency, a platform for the lone Cassandra who had said the whole project was folly, giving Nabat an influence out of all proportion to its circulation.71

Lavrov’s 1876 book, The State Element in the Future Society, was an attempt to answer his critics—to admit the need for some changes, while holding to his fundamentals. Lavrov was trying to square the circle of his antagonism to the State with his vision of a nation-wide revolution leading to a “libertarian”, Anarchist Utopia that could protect itself and its people. The summarise: Lavrov conceded an organisation would be needed for revolution and this would be a minority that would have to work in secret, use some violence to take power, and would have to hold on to power “temporarily” afterwards, albeit Lavrov suggested this organised minority should come from “the people” and only include “a small proportion of the intelligentsia”. Since Lavrov was one of the few revolutionaries who feared despotism, yet remained as hostile to law and constitutionalism as the rest of the intelligentsia, the only safeguard he could come up with to ensure the revolutionary minority relinquished power at the appropriate time was their own good nature—the selflessness and devotion of Chernyshevsky’s “New Men. Lavrov’s proposal for internal security was similarly unrealistic: what he called “direct people’s summary justice”—which strangely echoed a Nechayev slogan—was mob rule. Lavrov explicitly praised the American “Wild West” as a template. Lavrov piled contradictions one upon the next: he wanted a new world and abstract (Christian) morality; revolution without organisation; and a regime without rulers. It was a pitiful attempt and Tkachov was pitiless in response.72

Tkachov had earlier mocked Lavrov because if his scheme of educating people into socialism worked it would obviate the need for a revolution at all—and how could Russia reach Utopia without a cleansing bloodletting? Now, Tkachov sarcastically welcomed where Lavrov had come to see things his way: conspiracy, force, seizing power, a revolutionary government, and a minoritarian one at that—all of these things Lavrov had dismissed as Nechayevite lunacy a few years earlier. Tkachov taunted Lavrov for his half-heartedness and hesitancy in accepting these necessary measures, and then mercilessly took apart the rest of Lavrov’s scheme, which was, even by the standards of the Russian intelligentsia, the most fantastical flight of unreality. Relying on an organisation as broad and loose as Lavrov suggested would require a conspiracy so vast the secret police would easily discover and neutralise it. Lavrov’s worries about repression sullying the “justice” of a revolutionary government were dealt with summarily by quoting the unchallengeable Chernyshevsky: “whatever is useful for society” and promoting “human happiness” is “just”. Lynch law would obviously lead to civil war without end. And so on.73

There was no doubt among the Russian intelligentsia that Tkachov won the debate. The dissolution of the First International in July 1876 and Otto von Bismarck’s ban on the social democrats, the largest such party in the world, in October 1878, accepted without even token socialist or working-class resistance, reinforced Tkachov’s arguments against evolutionary socialism.74 Szamuely’s view was that both Tkachov and Lavrov were correct “in their own ways”, as demonstrated by 1917, and both “were infinitely nearer the mark than any ‘scientific’ Marxian analysis and prediction”.75 Tkachov was “prophetic down almost to the smallest detail” about how revolution would occur in Russia,76 and Lavrov was right about the dangers of such an eventuality from the perspective of someone who understood “freedom” in terms not wholly dissimilar to a Western liberal. What makes Lavrov a “tragic figure”, writes Szamuely, is that having been so perceptive in his diagnosis of the kind of system a minority-led revolution would create—it “would all come to pass, exactly as had foretold”—he remained so much “a prisoner of the Russian [revolutionary] tradition”, its assumptions and its prejudices against law and constitutional safeguards, that the only “antidote” he could offer “was ludicrously inadequate”.77

As important as Tkachov’s debate with Lavrov was his crossing of swords with Friedrich Engels, the bill-payer of Marx’s endeavours and one of Lavrov’s patrons. Enraged by Tkachov’s Tasks, Engels fired off a polemic against Tkachov in October 1874, consisting mostly of sneering personal attacks, intending to put this “immature schoolboy” in his place. Engels was to discover the Streisand Effect before it had a name. To Engels’ immense surprise, Tkachov replied in an “Open Letter”, saying that Engels had attacked him primarily because he saw him as an ally of Bakunin (which was true), despite Tkachov rejecting Bakunin’s central tenets of spontaneous peasant revolution and abolition of the State, and that Engels knew nothing about Russia (which was also true).78 Without omitting the jeers, and encouraged by Marx, Engels returned with a more substantive response in April 1875 that designated Tkachov a Bakuninist acolyte, poured scorn on the obshchina and other ideas of Russian specialness, as Marxists always had, insisting that without a bourgeoisie and proletariat Russia was further from socialism than Western Europe. Tkachov’s belief otherwise “only proves that he has still to learn the ABC of socialism”, Engels concluded.

Here was the first open clash between Narodism and Marxism. Marxism was held to have triumphed utterly, a view that would be given credence by two subsequent developments. First, this foundational debate—where the views were stated most honestly—would be replicated in various forms later in the nineteenth century by which time all factions involved called themselves “Marxist”. Second, Soviet historians would write up the debate as a devastating theoretical blow against Narodism and many in the West followed their lead. As Szamuely remarks, it is an “altogether … remarkable instance of the triumph of theory over reality”. The only sense in which Engels won was within the hermetic world of Marxist ideology, which of course he knew best. In Russia as it actually was, it was Tkachov who described reality, and foresaw and guided the Tsardom’s unravelling.79

Tkachov’s Long Shadow

Tkachov’s revolutionary career was short, like that of his one-time collaborator and ideological kin Nechayev (albeit not so short). Tkachov arrived as a central ideological node in the intelligentsia in 1874, and departed in 1880 when Nabat folded after Tkachov physically left Russia for France. In 1882, Tkachov contracted a mysterious brain illness and was confined to a sanitorium in Paris, where Tkachov died on 4 January 1886, aged forty-one. Hardly anyone attended Tkachov’s funeral, but Pyotr Lavrov did and delivered a warm eulogy, “magnanimous to the last”.80 (Lavrov died in the same city almost exactly fourteen years later.) But Tkachov’s impact was enormous. Under Tkachov’s guidance, the “Jacobin” creed was rediscovered by the Russian revolutionaries and they would never lose sight of it again.81

Tkachov himself was subject to damnatio memoriae—again like Nechayev, albeit again not so extreme. Among Tkachov’s own generation, his rebellious conduct in the highly conformist milieu of the Russian intelligentsia left scars that were never forgiven, and for subsequent generations, his shockingly honest writings contained a cynicism self-conceived idealists could not endorse. The substance of Tkachov’s ideas stuck, though,82 even if, in general, Tkachov would join Nechayev as an unspoken factor in revolutionary thought and practice, and explicit mentions of “Tkachovism”, whether by Narodniks or Marxists, tended to be accusations. The exceptions to this were telling. Narodnaya Volya and the Bolsheviks, the two most successful terrorist organisations, represented heterodox versions of Narodism and Marxism, respectively, and neither “bothered to conceal their admiration for many of Tkachov’s views”.83 It was through the latter of these that Tkachov secured an import place in the history of Russia, and ultimately the world, because of the influence he had over Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the terrorist-revolutionaries in their hour of triumph.

The interaction of Marxism with the Russian revolutionary tradition writ large is complicated and will be explored in detail in a subsequent article. For now, what is relevant is that the Marxist thread in Tkachov’s ideology was unorthodox because it was grafted onto Narodnik foundations with which it directly conflicted in important ways, that the “dialectic” as Marxism was integrated with and came to dominate the nomenclature of the terrorist-revolutionaries’ development after Tkachov left much of the Narodnik scaffolding standing, and thus it is no surprise that “Lenin’s Marxism was sui generis”, since he was the culmination of this movement.84 The Soviet Revolution tacitly conceded as much, naming its official theology “Marxism-Leninism”, an acknowledgment that Lenin had modified Marx’s doctrines. When Lenin’s actual life history is examined, it becomes clear Tkachov was a vital source of these modifications.

In Lenin’s formative period, while banished to Samara in 1891-92, he was taken under the wing of followers of Tkachov, Zaichnevsky, and other “Russian Jacobins”. In public over subsequent decades, Lenin, ever-sensitive to charges of ideological deviation and heresy, never objected to the accusations of “Tkachovism” and “Jacobinism”. On the contrary. Lenin’s public references to Tkachov were always favourable. In What Is To Be Done? (1902), the Bolsheviks’ revolutionary blueprint pointedly named in honour of Chernyshevsky, Lenin writes that the way “to seize power” was shown “by the preaching of Tkachov”, and in the summer of 1917, at the most critical moment of Lenin’s life, he published an article saying: “The Jacobins gave France the best models” and Jacobinism was “the only way out of the present crisis”. In private, Lenin read Tkachov, told his associates that Tkachov was “closer to our viewpoint than any of the others [in the revolutionary tradition]”, and recommended “familiarising yourself with Tkachov’s Nabat” to new recruits as the “basic” roadmap of the Bolshevik Party. Vladimir Bonch-Bruyevich, a close friend and head of Lenin’s private office, personally at Lenin’s side right through the turmoil of the Revolution its attendant civil war, wrote in his memoirs: “It is an irrefutable fact that the Russian revolution proceeded to a significant degree according to the ideas of Tkachov.”85

Marxist lexicography was too entrenched among the terrorist-revolutionaries by 1917 for Lenin to call his comrades to urgent revolution in Tkachov’s preventive terms, but Lenin’s stress on the opportunity of the relatively weak Russian bourgeoisie and the peasants suffering under the “survivals of feudalism” in the agrarian realm was obvious in its implications: both advantages were fading and action had to be taken quickly before further industrialisation and capitalist development foreclosed the possibility of revolution. This was consistent with Lenin’s earlier alarm at the agrarian reforms of Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin. At the meeting where Lenin convinced the Bolshevik Central Committee to initiate the coup, it was pure Tkachov. Lenin had little to say about the “objective conditions” and showered abuse on those who wanted to wait until the Bolsheviks had majority support to guarantee success. “Seizure of power is the point”, Lenin thundered, and History gives no guarantees. A chance was on offer and some of “the people” would assist as subordinate elements of the Bolshevik enterprise. Dealing with the rest of the people “will be clarified after the seizure”.86

During Lenin’s reign, Pokrovsky and other official Soviet historians were relatively open about the Bolsheviks’ debt to Tkachov. Lenin’s enthusiasm for Tkachov was genuine, and in any case Tkachov, as a student of Marx at a time when that was rare, the feud with Engels notwithstanding, was easier to integrate as an ideological—and especially operational—progenitor than Nechayev, who was still being acknowledged in this period, and not merely because of the extent of his influence on Tkachov. During Stalin’s “tidy-up” of the Bolsheviks’ origin myth, Tkachov was pruned, along with Nechayev, from the phylogenetic tree.87 Stalin’s purpose was to make the Bolshevik Party a straightforward descendant of Marx. The irony was that Marx the man had, soon after denouncing Tkachov, accepted he was correct—without ever admitting it.88

REFERENCES

Tibor Szamuely (1974), The Russian Tradition, p. 247.

Anna Geifman (1993), Thou Shalt Kill: Revolutionary Terrorism in Russia, 1894-1917, pp. 195-206.

The Russian Tradition, p. 247.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 247-248.

The Russian Tradition, p. 251.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 251-252.

Franco Venturi (1966), Roots of Revolution: A History of Populist and Socialist Movements in Nineteenth Century Russia, p. 361.

Stephen Carter (1991), The Political and Social Thought of F.M. Dostoevsky, p. 236.

Variously transliterated Pyotr Tkachev (or Peter Tkachev) and Pyotr Tkachyov.

The Russian Tradition, p. 252.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 252-254.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 253-256.

The title can also be translated as “Catechism of a Revolutionary” (Katekhizis Revolyutsionera).

The phrase is from Ernst Bloch. Quoted in: Philipe Buc (2015), Holy War, Martyrdom, and Terror: Christianity, Violence, and the West, p. 106.

Tom Holland (2019), Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind, p. 533.

Matthew 20:16.

Few of the Men of the Sixties adopted the “Nihilist” label for themselves, except for a brief period later in the decade and with some irony in most cases. “Nihilism” died out in the discourse even as an epithet within Russia by the 1870s, though it was used in Western reports about the Narodniks into the 1880s.

Anna Geifman (2010), Death Orders: The Vanguard of Modern Terrorism in Revolutionary Russia, p. 142.

A paradigmatic example of Nechayev’s relationship to the Narodniks can be seen in his views of the Decembrists. Nechayev embraced the Decembrist Revolt as a model of action. Nechayev wished the Decembrist conspirators had succeeded in exterminating the Imperial Family, placing him squarely in the mainstream of Narodism, which traced its lineage back to that set-piece confrontation on the square in Saint Petersburg in 1825 (and the forgotten roving rebellion in Ukraine). However, Nechayev faulted the Decembrists, as no orthodox Narodnik would, for being excessively invested in “theories”.

See: Christopher Read (1979), Religion, Revolution, and the Russian Intelligentsia, 1900-1912, p. 372.

There are superficial similarities in Nechayev and Bakunin advocating violent revolution that destroyed the State and society, but in method and intended outcome they were polar opposites. Nechayev redefined morality as whatever served the cause of an elite conspiracy leading to a revolutionary despotism. The Bakuninite Anarchists wanted a spontaneous popular revolution leading to a Stateless federation, and while this degree of upheaval had been considered frighteningly reckless by the Men of the Forties, the objection was basically tactical: Bakunin was arguing his case in conventional moral terms, using words like “freedom” in a way that would be broadly recognisable to a Western liberal and speaking of concepts like voluntary association.

This is not to say Nechayev had noadmirers among the Anarchists. He did, as he did across the rest of the intelligentsia since he was not a factional figure and his ideas were rooted in mainstream Narodism as Chernyshevsky had defined it. Perhaps the most notable Anarchist supporter of Nechayev was “Bidbei”, a privileged son of the capital who founded the Beznachalie Group during the terrorist revolt in 1905. Bidbei’s real name was Nikolai Romanov, oddly—the same name as the Emperor. Bidbei’s devotion to Nechayev was ostentatious and reflected in his behaviour, making him something of a black sheep even among the violent criminality of the revolutionary scene in the 1900s. See: Thou Shalt Kill, p. 135.

Albert Loren Weeks (1968), The First Bolshevik: A Political Biography of Peter Tkachev, p. 66.

The Russian Tradition, p. 258.

Religion, Revolution, and the Russian Intelligentsia, 1900-1912, p. 373.

Charles Ruud and Sergei Stepanov (1999), Fontanka 16: The Tsars’ Secret Police, p. 34.

Religion, Revolution, and the Russian Intelligentsia, 1900-1912, pp. 379-380.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 258-259.

Death Orders, p. 75.

Religion, Revolution, and the Russian Intelligentsia, 1900-1912, pp. 380-381.

Religion, Revolution, and the Russian Intelligentsia, 1900-1912, pp. 382-385.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 260-262.

Religion, Revolution, and the Russian Intelligentsia, 1900-1912, p. 364.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 260-262.

Ogarev was the person at Herzen’s side in 1827 when Herzen swore himself to revolution. The duo were walking in the Sparrow Hills above Moscow, ruminating on the Decembrists, according to Herzen. Later, Ogarev helped Herzen set up and run Kolokol, an incredibly influential revolutionary journal, published out of London from 1857 to 1865 and then Geneva from 1865 to 1867. Though banned in Russia, Kolokol circulated widely, reportedly being read by Tsar Alexander II himself. The termination of Kolokol was a marker that the Generation of the Fathers had been displaced as the dominant force of the intelligentsia: the journal condemned the assassination attempt against the Emperor in 1866, immediately lost a huge proportion of its readers, and then haemorrhaged subscribers to the point it had to close the next year.

For Nechayev to secure Ogarev’s collaboration in re-launching Kolokol in 1870, months after Herzen had died, was, therefore, an immensely significant political victory. Through Ogarev, Nechayev had a link—and a claim—to Herzen’s legacy, to the very foundations not only of the intelligentsia in the 1840s but the revolutionary tradition itself in the 1820s, and a tacit endorsement for his criticisms of where Herzen had gone wrong from the weightiest of sources.

Religion, Revolution, and the Russian Intelligentsia, 1900-1912, p. 381.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 262-264.

Michael Prawdin (1961), The Unmentionable Nechaev: A Key to Bolshevism, chapter eight.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 264, 268.

Religion, Revolution, and the Russian Intelligentsia, 1900-1912, p. 137.

Death Orders, pp. 75-76.

The Russian Tradition, p. 268-269.

Death Orders, p. 125.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 268-270.

Fontanka 16, pp. 34-37.

Amy Ronner (2021), Dostoevsky as Suicidologist: Self-Destruction and the Creative Process, p. 183.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1872), Demons, p. 394.

The Russian Tradition, p. 271.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 271-276.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 276-278.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 278-279.

The Russian phrase, “Хождение в народ”, might literally be translated as, “Walking into the People”.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 279-280.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 280-283.

The Russian Tradition, p. 272.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 285-286.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 285-286.

Michael Karapovich (1944, July), ‘A Forerunner of Lenin: P. N. Tkachev’, The Review of Politics. Available here.

The Russian Tradition, p. 288.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 288-289.

Named for the French revolutionary theorist Louis Auguste Blanqui (1805-81).

Karapovich, ‘A Forerunner of Lenin’; and, The Russian Tradition, pp. 288-291.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 291-305.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 291-305.

In Tkachov’s writings in the late 1860s, where he was arguing for the necessity of political revolution, against the idea that social revolution could begin itself or be instigated by propaganda, he wrote: “It is absurd to expect a natural transition from the old regime … Everyone ought to know that this transition requires a certain jump”. Tkachov went on to try to ground this argument for “jumps” in historical precedent, and cited the 1524-25 Peasants’ War, a massive, Anabaptist-inflected rebellion actually of the better-off peasantry in Germany at the dawn of the Reformation. Tkachov had picked up this precedent from Engels’s The Peasant War in Germany (1850). Tkachov’s argument was that the rebels had not failed because of inherent weaknesses and the extremism of their program. Rather, said Tkachov, the rebellion failed because of disorganised and indecisive leadership, and not uniting around the extremism of Thomas Muntzer, giving too much space to the burghers and other moderate elements who tried to improve the existing system instead of uprooting it. “[T]hose men whose opinions are generally considered to be Utopian actually are much more practical than those timid reformers who enjoy the reputation of wise and farsighted statesmen”, Tkachov concluded. See: Karapovich, ‘A Forerunner of Lenin’.

The Bolsheviks absorbed Tkachov’s basic worldview, of course: Lenin’s revolution was premised on his organisation with cult-like discipline, regarded as extreme even by the other radical socialists, bringing off a minoritarian coup that cascaded into an apocalyptic civil war, which would give him tabula rasa to implant Communism. And the Peasants’ War would become a particular reference point in the Bolshevik world, part of the History they were vindicating. This was especially notable after the Bolshevik conquest of East Germany and the creation of their “German Democratic Republic” (DDR) colony, where a cult was fostered around Muntzer.

350 streets in the DDR were named for Muntzer, as were mines, industrial plants, schools, even a regiment of the National People’s Army. In 1956, a highly influential DDR film portrayed Muntzer as the heroic leader of the “peasants and plebians”, while Martin Luther—whose opposition to the rebels is infamous—was cast as a class traitor and collaborator with the aristocracy. Muntzer appeared on the DDR currency down to the end, and in an enormous painting—46-foot tall and 404-foot wide—by Werner Tübke of the Battle of Frankenhausen (1525), completed in 1987 and named The Early Bourgeois Revolution in Germany. Instructively, the former Franciscan monastery church in Mühlhausen was transformed by the DDR in 1975 into “one of the most important monuments to the German Peasants’ War” and “an important place for worshipping Müntzer”. See: Gianmarco Braghi and Davide Dainese (2022) [eds.], War and Peace in the Religious Conflicts of the Long Sixteenth Century, p. 128.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 296-297.

The Russian Tradition, p. 306.

Karapovich, ‘A Forerunner of Lenin’.

The Russian Tradition, p. 291.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 322-324.

Karapovich, ‘A Forerunner of Lenin’; and, The Russian Tradition, pp. 302-306.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 302-313.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 292-294.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 300, 315-316.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 307-314.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 307-314.

The Russian Tradition, p. 314.

The Russian Tradition, p. 307.

The Russian Tradition, p. 297.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 310-311.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 294-299.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 299-301.

The Russian Tradition, p. 315.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 300-301.

Karapovich, ‘A Forerunner of Lenin’.

The Russian Tradition, p. 315.

Karapovich, ‘A Forerunner of Lenin’.

See also:

Orlando Figes (1996), A People’s Tragedy: A History of the Russian Revolution, 1891-1924, pp. 137, 145-146. “It was not Marxism that made Lenin a revolutionary but Lenin who made Marxism revolutionary”, is Figes’s rather striking formulation (p. 146).

Richard Pipes (1960, Oct.), ‘Russian Marxism and Its Populist Background: The Late Nineteenth Century’, The Russian Review. Available here.

Simon Clarke (1998, Jan. 1), ‘Was Lenin a Marxist? The Populist Roots of Marxism-Leninism’, Historical Materialism. Available here.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 316-318.

Karapovich, ‘A Forerunner of Lenin’.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 318-319.

The Russian Tradition, pp. 379-85.

Fascinating and impressive article. I never knew any of it.