Salem on the Eve of the Witch Trials

This is the first of a three-part series looking at the Salem witch trials, which began 333 years ago this month. This first article will look at the creation of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, its nature, and the conditions prevailing on the eve of the witch panic. The second article will trace the outbreak of the witch panic in Salem, the issues that shaped its course as it spread through Massachusetts, and the trials. The third article will examine how the witch craze ended and why it has had such an enduring legacy.

EUROPE, THE AMERICAS, AND THE REFORMATION

The European discovery of the Americas, inaugurated with the Spanish landing in the Caribbean on 12 October 1492, was an extraordinary moment in human history, bringing together two populations that had developed in isolation for 11,000 years,1 unaware of each other’s existence for more than 500 generations.2 Even the most powerful Native polities, the Aztecs and the Incas, were swiftly overwhelmed: the superior Spanish technology was buttressed by vast numbers of Native allies eager to humble these aggressive, recently-formed Empires that had dispossessed them. More devastating than any military defeat was the diseases the Spanish had unknowingly brought with them, most notoriously smallpox.3 Lacking immunity, half or more of the American Natives perished.4

Native populations began physically recovering later in the sixteenth century, as the pandemics abated and the rulings of the Roman Catholic Church forced changes to Spanish governance. The lifeways of the Natives were gone for good, though. For structural reasons, paganism has never been able to effectively resist Christianity, and in the New World the Roman Catholic missionaries were particularly motivated to sweep away cults they regarded as manifestly demonic after the discovery of such widespread human sacrifice.5 The tradition of Christians combating Satan’s machinations in the Americas, thus the road to the Salem witch panic, had begun.

Spain was uncoupled from the Holy Roman Empire when World Emperor Charles V abdicated in 1556. Under Charles’s son, Philip II (r. 1556-98), Spain emerged, with its New World possessions and the treasures therein, as a superpower and leading combatant in the great civil war that was underway in Latin Christendom. The Protestant Reformation had begun in the 1520s and quickly splintered and spiralled into violence, within itself and against Catholics. The Reformers believed the Roman Church was comprised of the “scum of Satan”,6 whose interpretive monopoly had been corrupting the Christian people for a millennium by seducing them into unscriptural deviances like the worship of Saints and statues of the Virgin Mary. Christians should proceed sola scriptura (by scripture alone), the Protestant Reformers maintained: trusting the Holy Ghost, not the Roman cardinals and other agents of the Antichrist, to reveal the meaning of the Bible’s text. The dual effect, so important in setting the stage for Salem, was to make the Protestant movement highly schismatic—the Holy Ghost had a dreadful habit of revealing different things to different readers7—and intrinsically accepting of the idea of witches.8

The period of apparent calm and coexistence when Philip acceded would not last,9 not least because of Philip’s determination to prosecute the Counter-Reformation, officially proclaimed by the Papacy in 1563, in the most uncompromising fashion.10 If there was any one point of no return, it was the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1572, the Catholic French Monarchy’s extermination of the Huguenot (Protestant) leadership that triggered a genocidal wave of mob slaughter against ordinary Huguenots throughout the whole country. England’s heretofore realpolitik approach became impossible. It was in the context of Europe’s geopolitics being reformulated along strictly sectarian lines that the Pope blessed as a Crusade the Spanish Armada sent in 1588 to “recover” (conquer) England for the Roman Church. The respite at the end of the sixteenth century and beginning of the seventeenth was merely a period of recuperation for exhausted combatants before the final showdown of the Thirty Years’ War (1618-48), which ultimately convinced both sides that total victory was impossible and should not be attempted.

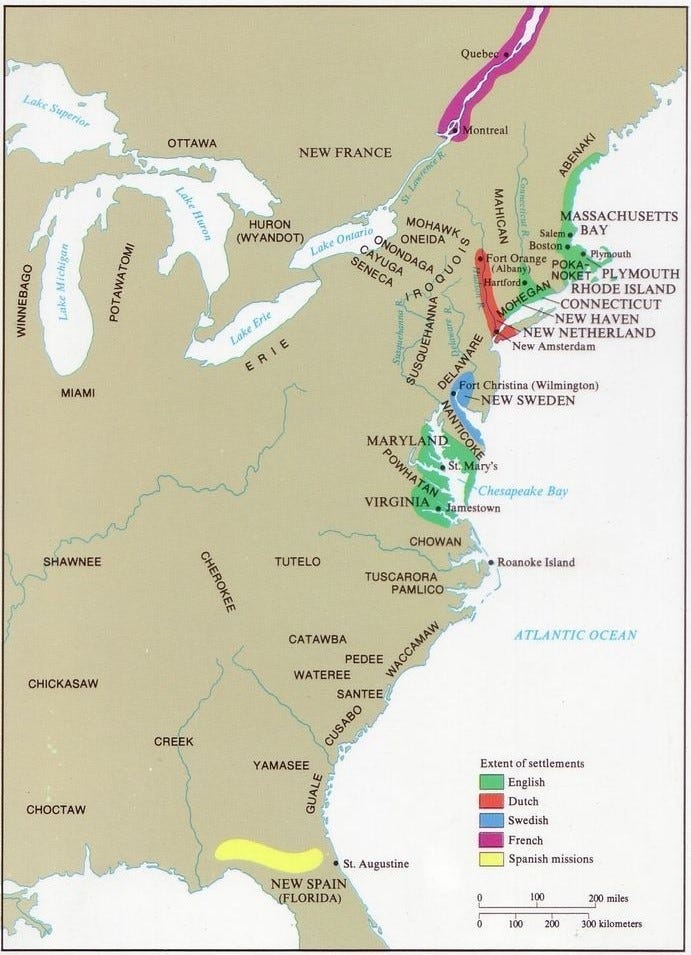

Throughout this period, many Europeans, often from fringe Protestant sects trapped between the Roman Church and the Magisterial Reformers, sought safety and religious freedom in America.11 This transformed America in two main ways. First, it diversified the European holdings—and brought the conflict implicit in that. Until the early 1560s, Europeans in the New World were overwhelmingly Spanish, with some Portuguese on the coast of Brazil and the French in Quebec—all of them Catholic. The arrival of Protestants thereafter was not readily accepted. For example, a terrible foretaste of what was coming on the Day of Saint Bartholomew was visited on the Huguenots in Florida by the Spanish in 1565.12 Second, it meant Europeanization in the Americas was expanding.

ENGLAND’S REFORMATION AND ARRIVAL IN THE NEW WORLD

While England was a slightly special case in this matrix—in the issues at stake and the timing of its religious conflict—it was broadly caught up in the same trends, of demands for (and resistance to) official Reform, and minoritarian flight to America.

Elizabeth I (r. 1558-1603) sought to compose England, after the rapid alterations in official confession that preceded her, with a compromise that left the Church of England, in the famous phrase, both Catholic (in structure) and Reformed (in theology). Protestantism of a really quite radical Calvinist kind bedded down remarkably quickly as the overwhelming majority religion in a country that had been known since the eleventh century as the “Dowry of Mary”, such was its devotion to the Virgin Mother, a tradition now dismissed as superstition and idolatry.

The battleline in England was, therefore, not Protestant-Catholic, but between those Protestants who accepted the Elizabethan Settlement (Anglicans) and those Protestants (“Puritans”) pushing for the Revolution to go further.13 Despite Elizabeth confronting Spain—the embodiment of evil above even France to English Protestants—the Puritan movement repeatedly challenged her and gained momentum throughout her reign, but the Puritans were marginal enough and the Queen adept enough that the issue was contained.

The English-language King James Bible produced in 1611 under Elizabeth’s successor, James I (r. 1603-25), was partly to accommodate the Puritans, but in general James took a hard line. “No bishop, no King”, James memorably told the Puritan representatives gathered for a conference with Anglican bishops at Hampton Court in January 1604, adding: “I shall make them [that reject my religious policies] conform themselves, or I will harry them out of the land”.14 In the event, they left of their own accord.

It was during James’s reign English settlements were established in the New World. There had been one earlier attempt to found a colony, on Roanoke Island in what is now North Carolina in the 1580s, but it had failed, resulting in one of the great mysteries of Colonial America. The colony founded at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607, stuck—just. The winter of 1609-10 would be remembered as “the Starving Time”, when the Jamestown population of 500 was literally decimated amid scenes of cannibalism. Then the English set down at Newfoundland in Canada in 1610. These two colonies remained largely Anglican and commercial, but an infrastructure and template now existed for those who wanted to leave England and begin again.

THE PURITAN MOMENT: SETTLING AMERICA, REVOLUTION IN ENGLAND

As Puritans despaired of reforming England from within, the idea of reforming from without took hold. In November 1620, the first Puritan settlement in America was established, the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts, whose initial inhabitants—enshrined as the Pilgrim Fathers—were transported aboard the Mayflower. James had been happy to see the Puritans go, and his son, Charles I (r. 1625-49), was of the same view. The small Puritan settlement created under John Endecott at Naumkeag (Salem) in 1628, just to the north of Plymouth Colony, was to become the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

The schismatic nature of the “hotter” Protestants was on display again here: the Puritans of the Plymouth Colony were “Separatist”, wanting total severance from a Church of England they saw as beyond redemption, while the Massachusetts Bay founders were “Non-Separatist” Puritans who sought to create a pristine godly community in the New World, insulated from the corruptions of England, which could guide the reform of the Church from the inside—hence the famed speech of John Winthrop about Massachusetts’ being created as “a city upon a hill”, a shining example to the rest of Christendom.15 This difference is why Massachusetts Bay had a Royal Charter granting nominal protection and broad autonomy, and Plymouth did not.

Puritanism grew rapidly in England from the 1620s, against the backdrop of the Thirty Years’ War, and made particular inroads in the English elite. Parliament became dominated by the Puritan gentry, with momentous consequences. Charles launched the intervention to vindicate the Protestant cause on the Continent that Parliament clamoured for—only for Parliament to refuse to fund it properly, leading to defeat and national dishonour. Parliamentary intransigence over the budget became habitual, and innovatory claims of Parliamentary authority, over areas as self-evidently outside their purview as foreign policy and the King’s domestic arrangements, were advanced.16 England’s latent fear of Roman Catholicism, in the shadow of the Spanish Armada and the Gunpowder Plot, became overt and at times quite hysterical among the Puritans by the late 1620s. Despite Charles I’s stringent measures against Jesuit infiltrators and any hint of Catholic proselytising, the Puritans increasingly diverted Parliament from governance issues to demands that private recusants be persecuted and focusing on fantastical “papist” plots. Inevitably, the conspiracy theories started centring on Charles’s French Catholic wife.17

The fusion of Puritan ideological and procedural radicalism was threatening the functioning and defence of the State. Having continued trying to find moderate partners in Parliament long after it was clear there were none,18 Charles gave up, beginning a period of Personal Rule in 1629 that lasted until 1640. Puritan accusations the Court was a nest of “popery” intensified.19 The King’s program to harmonise the Church under Archbishop William Laud did nothing to heal the divide, and in its tactics sometimes pushed away reconcilable elements.20 Convinced the “mischievous designs” of Rome were ascendant, a “Great Migration” took 20,000 English Puritans to the New World in these eleven years.21 (Winthrop’s speech was delivered in 1630, at the start of this wave of emigration, to a group of colonists about to depart England.) However, any hope that draining extremists out of the realm would reduce tensions was to be bitterly disappointed.

In the face of revolt in Ireland and war with Scotland, Charles recalled Parliament in 1640, the fateful step that allowed the Long Parliament to lock itself in place and push England over the brink into Civil War in 1642, the last War of Religion, which ended with Charles being “executed” by the Puritan rebels in 1649. Instead of pacifying England, the Puritan colonies had served as a reserve base of support for the rebels. Hundreds and maybe thousands from the “Puritan diaspora” flooded back into England as the English Civil Wars loomed, and continued coming once the conflict was underway. Such returnees were among the key actors in making what had seemed an impossible dream a reality: a Puritan-ruled England with neither bishop nor King.22

Vindication seemed to be at hand for the Puritans. England was being remade according to the example of godliness preserved in New England, and the purity of the colonies was being rewarded with God’s material favour.23 Massachusetts had quickly established a thriving economy and by the early 1640s Boston was converting its economic power into political power, extending its control over New Hampshire and Maine to the north where the sources of wealth—furs, lumber, and above all fish—were located. Massachusetts had become an Imperial power in its own right, not merely the extension of one, and under the Commonwealth and Protectorate this expansionism was smiled upon from London.24

The Puritan idyll proved to be a mirage. In England, the Interregnum was a brief, chaotic, and futile series of experiments in redefining “the people” to fit the designs of the Puritan officers. With the death of Oliver Cromwell in 1658, none had the force of personality to hold back the tide in a country that yearned for a King. For Massachusetts residents, this was a personal failure and an ideological challenge. The Puritan conviction that they had been touched by the Spirit, made one of the elect “saints” bound for heaven, was not final. Tormented with self-doubt and feelings of unworthiness, Puritans constantly re-examined this presumption about themselves and their communities.25 To have their city upon a hill light the way for England’s reformation, only for it all to melt away so quickly, called into question their mission. Was it folly? Did they merely need to redouble their efforts? Could they? As the second generation came of age in New England, some doubted those without personal experience of conversion by the Spirit could carry the burden of the godly commune, and London was set to make that burden heavier.

RESORATION ENGLAND AND THE MASSACHUSETTS BAY COLONY

The Restoration in 1660 brought to power the slain King’s son, Charles II (r. 1660-85), who immediately began a global hunt for the Regicides, led at first, interestingly, by another returnee, a rebel defector, Sir George Downing, whose Anglo-Irish Puritan family raised him in Salem. This was a unique period, lasting over a decade, when kidnap and assassination operations abroad had a higher priority than at any other moment for England’s intelligence services.

Several of the Regicides fled to America—the best-known are William Goffe and Edward Whalley—and it was in the Massachusetts Bay Colony they hid from the King’s justice. The main problem for Royal agents pursuing Goffe and Whalley in the New World was the general sympathy of the American colonists for “the Good Old Cause”, the beginning of a problem for Royal authority in America that formed a key part of the context for the Salem witch panic—and, of course, in the long-term led to secession.26

Relations between England and the Massachusetts Bay Colony deteriorated for the remainder of Charles II’s reign.

Some issues were material. The difficulties of State finance that had been tangled into the religious divisions leading into the Civil Wars had plagued the Protectorate and afflicted Restoration England. One of Charles II’s answers—building on a Cromwell policy—was the Navigation Acts,27 This worked as far as England’s finances went, and hit the colonists’ bottom line hard.28 Additionally, a key objective of the Navigation Acts was to undermine Dutch naval supremacy. That worked, too—economically. Unfortunately, the Dutch responded with war (1665-67), as they had the first time (1652-54), the difference being that chroniclers could write of Cromwell having “made all the neighbour Princes fear him”. Nobody would say that of Charles II, a dissolute “merry monarch”, who was forced into a hasty peace treaty after the Dutch utterly humiliated him with the Raid on the Medway in June 1667. The Medway fiasco dented Royal authority in the colonies, and it was about to take another hit.

The expansion of New England by 1670 to accommodate a population over 50,000 increased tensions with the surrounding Native Americans. King Philip’s War raged from 1675 to 1678, one of the largest wars in the Americas since the arrival of Europeans. Though it ended with a decisive victory that secured southern New England and steadily assimilated the remaining Natives in the area into the English economy and culture, the cost had been terrible.29 Perhaps 2,000 Puritans were killed, many settlers were taken into slavery (and many settlers took slaves), and numerous villages burned to the ground. Moreover, the Native invaders had come close to taking Boston, fifteen miles south of Salem, which would have been terminal for the Colony. The experience of an existential challenge was no secular event for Puritans, and the religious interpretation had a dual effect.

On the one hand, the sense of cosmic danger the colonists felt during the war never lifted. Increase Mather—later an important figure in the Salem events—was far from alone in seeing the ravages the Natives inflicted on the “English Israel” as a warning from God, as a call to “see for what sins those judgments” had been sent and to root out these sins, lest the Puritan polities end up like the old Israel, demolished by heathens and their people scattered.30 The fear of physical annihilation was in some ways secondary to the fear that land won for Christ would revert to paganism—which to many English Protestants and certainly to Puritans often blurred with Catholicism.31 Indeed, Puritans often saw hostile “Indians” as joined to, or as agents of, “papists”, hellbent on the destruction of the True Reformed Faith.32

On the other hand, having prevailed, Puritans felt they must be broadly on the right track, albeit perfection could never be reached, thus God left Native “thorns” in their sides to admonish backsliding. Mather credited God’s “destroying Angel” for saving the colonies,33 and since England had provided no direct assistance, it seemed all the more plausible. This was a waymark in the trends of diverging interests on the Native issue—the non-Puritan authorities in England wanted peaceable relations, seeing the colonists’ expansionism as troublemaking—and New England outgrowing the Mother Country. But it was more than that. While the New Englanders were growing in confidence they could handle their own affairs, developments in and from London suggested that, if the Puritans wanted to keep the heavens onside, perhaps they should.

Charles II raised Puritan hackles with his Act of Uniformity (1662), reheated Laudianism as far as the Puritans were concerned, and antagonised the Puritans from the other direction with his Declaration of Indulgence (1672). While the latter act lifted legal restrictions on Dissenters (as Protestants outside the Anglican Church were now called), which the colonists might be expected to like, it also challenged the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s laws disenfranchising non-Puritan Protestants and—most importantly—it lifted restrictions on Roman Catholics. To make matters worse, when Parliament retaliated against the Indulgence with the Test Act (1673)—requiring State officials to take oaths abjuring Catholicism—the King’s brother, James, the Duke of York, resigned as Lord High Admiral, an admission he was a Roman Catholic. It fed into the deep suspicion that Charles II was a secret Catholic—and, for once, the Puritans were quite correct.

After twenty years in exile in France, Charles II had taken up France’s official faith and returned to England as a client of its “Sun King” Louis XIV (r. 1643-1715), an arrangement formalised in a secret treaty in 1670. This fact is one reason why Charles II was so hesitant in dealing with the Popish Plot (1678-81), an episode of sheer anti-Catholic hysteria. Wild as the accusations of Titus Oates were, none were as unthinkable as the English King being a hireling of the French Monarch, and that was true. Charles II’s strategy was to avoid doing anything that invited anybody to look too closely at Royal affairs (at least the political and economic ones).

The Popish Plot itself, near-ubiquitously believed in New England, alienated the colonists yet further from London, and on the heels of King Philip’s War added to the colonists’ dread that their doom was near, brought about by Indian attacks from without and Romish corruption from within. Charles II’s actions afterward in trying to prevent another Oates destabilising the realm—essentially by centralising authority—only made things worse. The Massachusetts Bay Colony—on the basis of its laws penalising non-Puritans, among other things—was held to have violated the terms on which was founded by the Court of Chancery in 1684, and subsequently its Royal Charter was revoked, annulling its right to self-government and bringing it under direct Royal rule.

THE RISE AND FALL OF ENGLAND’S LAST CATHOLIC MONARCH

Matters went from bad to worse for the Puritan colonists when Charles II died and his brother became the overtly-Catholic King James II (r. 1685-88). James reorganised the English colonies as a single Dominion of New England ruled by a Governor, Edmund Andros, whose insistence on extensive religious toleration would have been resented even if he had not been so high-handed. The arrival of thousands of French Protestants in England in late 1685 after France’s “Sun King” put a final end to the Huguenot presence inflamed things further, activating the latent English Protestant sense that the Devil worked through the Roman Church and its Princes, like James II.

For the colonists, at least, the nightmare was short-lived. James II was autocratic, Catholic, and vindictively sectarian. He had, for example, immediately started Catholicising the army and bureaucracy, purging Protestants. It was a combination seemingly designed to embitter Whigs. James could have held the Tories, who will accept a lot from an anointed King, if he was not also clumsy. In audaciously trying to form an alliance with the Dissenters, the political centre collapsed.

In a coda to the Civil Wars, at the invitation of the Parliamentary elite, the Dutch stadtholder William of Orange landed in England in November 1688, putting James II to flight. Uniquely, when subsequently crowned as William III (r. 1689-1702) on 11 April 1689, it was a double coronation, alongside his wife, James’s own daughter, who became Queen Mary II (r. 1689-94). This episode, commemorated as the Glorious Revolution, is sometimes dismissed as a “Whig coup”, but it inaugurated the genuinely revolutionary process of leaching powers from the English Monarch and instituting ever-more total Parliamentary supremacy.34

Once news of the Glorious Revolution reached the Americas, residents and militiamen in Boston formed an orderly mob for a bloodless coup against Governor Andros on 18 April 1689. The Dominion was disbanded and Andros, the two-dozen or so Royal troops, and any identifiable Anglicans in Boston were imprisoned. The Governor and his troops were sent back to England. Notably, the proclamation of this regime change mentioned the “horrid Popish Plot” in its very first sentence, and framed their actions as a response to this scheme “wherein the bloody devotees of Rome” planned “the extinction of the Protestant religion”. The Bostonian putschists concluded by praising “the noble undertaking of the Prince of Orange to preserve the Three Kingdoms from the horrible brinks of Popery and slavery”, and vowed to work with him to restore their “English liberties”. The removal of Andros was almost the last thing the people of Massachusetts would agree on until the witch panic three years later.

THE FALLOUT OF THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION IN MASSACHUSETTS

In the wake of the Glorious Revolution, Massachusetts recovered self-government, with unhappy results.

William III’s reign opened with a bitter fight to defeat the Jacobite counter-revolutionaries backed by France gathered in Ireland,35 and the Williamite war spilled into the broader Nine Years’ War (1688-97), basically an effort by England, the Dutch Republic, and the Habsburgs (both Austria and Spain) to tame the French behemoth, a fusion of Protestant States’ anger over the Sun King’s persecutions and Catholic States’ concerns about his expansionism.

The Nine Years’ War reached the New World in February-March 1690, with the French and their Native allies attacking the English colonies. Here was the Puritans’ darkest fears confirmed: “Papists … in league with the Indians to massacre Protestants”.36 Franco-Indian raids, frequent and in force, displaced most of the people in the North of New England and the economy was in free fall. The Puritan colonies believed themselves to be in existential peril—again, barely a decade after the last experience.37 Attack—and ineffective Puritan counter-attack—continued throughout 1690 and 1691. A poor harvest in Massachusetts in late 1691—partly a result of simply being unable to reap their crops because of the raids over the summer—added to the physical hardship.38

On 25 January 1692, there was a terrible slaughter of Englishmen in York, about sixty miles up the coast from Salem.39 This was right around the time the witch panic was stirring, and the war continued all through the events over the next year. The psychological strain due to the constant fear of death was the least of it. The Puritans saw the war as God’s punishment for the Colony going astray, and if they had been misled it must be by the Devil amongst them. The stakes were cosmic. Failing to find and neutralise the Satanic infiltration would consign them to perdition—and generations after them, who would be deprived of the path to salvation offered by the Colony and its example.

To pay for the war, taxes had to be raised in Massachusetts, and the franchise was expanded, in theory ensure consensus. In practice, it furthered divisions as it brought younger men to the fore, who were personally ambitious in a way the elders of the 1680s they displaced were not. Factions had multiplied and hardened as the colonists sought a settlement after the Glorious Revolution—a process analogous to the consolidation of the political parties in England after 1689. To have inexperienced men as the managers of this was not ideal, and Puritans saw the Devil’s hand in the escalating political turmoil, too.40 These problems were particularly acute in Salem, which was already notorious, even by the standards of Puritan colonies, for its infighting. Salem village squabbles could become generational feuds.41

Salem’s individual animosities had, by 1691, somewhat consolidated into one major, public dispute, which had become a central religio-political dividing line. The dispute was over the town’s minister, Samuel Parris, who had only arrived on 18 June 1689—and in whose home the Salem witch panic would begin.42 A faction wanted Parris removed, and they were gaining momentum. Parris had a difficult assignment. Salem had, after all, deposed numerous previous ministers, including George Burroughs (an important character in the story to come).43 But it is fair to say Parris authored some of his own troubles. Though a gifted preacher—Parris’s worst enemies would concede that—he was not skilled at the social side of the job. Disputes raged in Salem under his management, and Parris added to them by applying his rigorous standards to high-status Salem residents, chastising them in public for trivial offences, a seemingly-wilful targeting to take them down a peg or two.44 When Parris did unite Salem, it was against him: his salary was effectively withdrawn in October 1691 when most parishioners refused to pay him any more.

The social discord in Salem fuelled the deteriorating political situation: the government could come to no solution for the economy and effective war-making, and this bred further conspiracy and backbiting. Hope for stability emerged on 7 October 1691, when the negotiations between the Colony and the Crown were finalised. The new Charter granted unprecedented privileges, and granted to the Colony—to be renamed the Province of Massachusetts Bay—recognition of its ownership of Maine, and added to it the Plymouth Colony and Nova Scotia (now Canada). Less pleasing was the institutionalisation of religious liberty—Massachusetts would no longer be officially Puritan—and the re-establishment of direct Royal rule. Moreover, the status of Massachusetts’s legal arrangements remained unresolved, and there were grave doubts about the competence of the new Royal Governor, Sir William Phips. The news of Phips’s appointment arrived in Salem in late January 1692, and, whatever their misgivings, many looked forward to someone other than their current leaders running things. But Phips would only actually arrive in May.45 This meant four more months of ineffectual leadership. It was in this interval that mania took hold of Phips’s Province.

REFERENCES

When humans emerged, maybe 200,000 years ago, probably in East Africa, the two continents had been separated for tens of million years. However, 35,000 years ago, a land-bridge across what is now the Bering Strait became passable, and 15,000 or so years ago the first humans took the road to the New World. 11,000 years ago, “Beringia” was submerged again, and the populations of the Americas and Eurasia were separated.

There is one known exception: the landing of Norsemen (“Vikings”) in North America around 1000 AD. The Icelandic Sagas tell of an expedition led by Leif Erikson, son of the founder of the Norse polity on Greenland, reaching “Vinland”, which, from the description, appears to be Newfoundland in what is now Canada. The archaeology has since reinforced this presumption, discovering a site known as Meadows Cove (L’Anse aux Meadows). What the Norsemen established can be called a settlement or a colony, but is better described as an outpost: there was never more than 150 people present in the Cove at any one time. Most estimates are that the outpost only lasted five or ten years, though there are some who argue it lasted nearly a century.

At all events, the Norsemen did not venture very far inland in North America, much less colonise the whole continent: the impact—culturally, biologically, and otherwise—of this contact was negligible on both sides of the Atlantic. Erikson’s discovery came in the twilight of the “Viking Age”: by the time he had made it, Iceland had officially converted to Christianity and missionaries were hard at work on Greenland. Amid such upheavals, it is dubious whether anyone beyond Erikson’s homeland heard of his discovery, even in the remnants of the Norse world; there is no evidence anybody outside that ever heard of it until the twentieth century.

There is a widespread belief—summed up in the phrase “smallpox blanket”—that Europeans practiced essentially biological warfare against Native Americans, and, therefore, the ravages of disease were not a terrible unforeseen disaster, but a premeditated genocide. This is a myth, based on a common fallacy in conspiracy theories, namely “the assumption that you can infer subjective intention from objective consequence”. There is no evidence whatsoever that the Spanish even considered “pox blanket” tactics against the American Natives, and this is no surprise since germs were not widely understood in the sixteenth century. There is one single documented case, from much later, of a European power attempting such a thing.

In the nineteenth century, a letter was discovered from Sir Jeffery Amherst, commander-in-chief of the British forces in North America, to Colonel Henry Bouquet at Fort Pitt in Pennsylvania, during the French and Indian War, a theatre of the Anglo-French Seven Years’ War (1756-63), which was the first true world war. Amherst is quite explicit that in the desperate situation the British found themselves, “every stratagem” had to be used, including the transfer of items—blankets among them—contaminated with smallpox to the Natives. Bouquet responded equally explicitly that he would try, while “taking care however not to get the disease myself”. It is telling that this exchange of letters took place in 1763, a year after Marcus Antonius Plencic had made germ theory a part of the public discussion in Enlightenment Europe.

While we cannot be sure that Bouquet actually did attempt to pass smallpox blankets to Native Americans, unknown to either him or Amherst, William Trent, a trader and militia captain in Delaware, had already had the idea and put it into operation. (We know of the story from Trent’s diary.) But there is no evidence it worked. It is absolutely plain that the smallpox outbreak among the Natives around Fort Pitt in the spring and summer of 1763 had spread from other nearby Native populations. The historical evidence suggests Trent himself was aware he had failed. Philip Ranlet of Hunter College, who has written on this controversy, noted: “Trent would have bragged in his journal if the scheme had worked. He is silent as to what happened.” Moreover, there is grave scientific doubt the scheme could work.

The historical reality of British failure with this scheme is hardly a defence of them, of course: to have contemplated, let alone attempted, to spread indiscriminate death in this manner was an outrage to morals and the laws of war even by the standards of the time.

Peter Fibiger Bang, C. A. Bayly, and Walter Scheidel (2020), The Oxford World History of Empire, pp. 473-75. In terms of the actual numbers, as against the proportions, of Native inhabitants killed by pathogens, there is some uncertainty. Older estimates of the total pre-Columbian Native population—in North and South America—were around 120 million, relying mostly on documentary evidence and projections. More recent estimates, based on harder evidence that technological advances have opened up, point to a much lower total around 40 million. See: Kyle Harper (2021), Plagues Upon the Earth: Disease and the Course of Human History, pp. 252-53.

Fernando Cervantes (2020), Conquistadores: A New History of Spanish Discovery and Conquest, pp. 208-09.

Martin Luther (1545), Against the Roman Papacy, An Institution of the Devil. A lengthy excerpt can be found here.

Luther was challenged on this central element of his theology right at the beginning of his Revolution, in late April 1521, while he was in Worms for the Diet where he was made to answer to the Emperor for his preaching, the great confrontation that is the true beginning of the Reformation. At a dinner, Luther was questioned by Johann Cochlaeus, a Christian humanist who had some sympathy with Luther’s critiques of the Roman Church: How could Christianity retain any integrity if everyone was entitled to interpret it for himself? Luther’s answer was that the Spirit would ensure the meaning of God’s Word was illumined. Cochlaeus found this inadequate and pressed the point, following Luther back to his room to continue the debate. Luther never got any further in explaining how disputes in interpretation would be settled, and the self-evident danger of chaos augured by this insouciance remade Cochlaeus into one of Luther’s most ferocious opponents, especially after his dread was realised in the Farmer’s War in 1524-25, a massive uprising in southern Germany by Protestants who had very much done their own research.

As Cochlaeus later explained his view: “How will the Scripture be the principal and only Judge in the Council (as the Lutherans want it to be), since by itself the Scripture neither forms an opinion, nor understands it, nor is able to express it? In saying this I would by no means detract from the Sacred Scripture, which I … hold as sacrosanct, and on which I depend, and from which, as a knowledgeable and prudent man, I would not depart by even a finger’s breadth. But in controversies I do not demand Scripture’s true meaning from Scripture itself, since it does not know how to speak; but rather from the Holy Fathers, who spoke after they were inspired by the living Spirit of God; or from the Roman Pontiff, whom Christ Himself questioned concerning his faith; or from a General Council, in whose midst Christ Himself is and the Spirit of Truth emerges … For that Spirit lives, not in the dead letters, but in the living Body of Christ, which is the Church, which [the Spirit] directs as the soul does the body … Divine Scripture orders that in controversies we should go, not to the mute Scripture, but to the Highest Priest … Thus Christ orders us to hear not silent letters, but the Living Church.”

See: Elizabeth Vandiver, Ralph Keen, and Thomas D. Frazel (2002), Luther’s Lives: Two Contemporary Accounts of Martin Luther, pp. 298-99.

The spasms of Protestant iconoclasm that were frequently the provoking incident for popular violence in the early phase of the Reformation often focused on Marian statues, associated by Reformers with sorcery. In Catholic perception by the end of the Middle Ages, Mary verged on displacing the Holy Spirit in the Trinity, and she even somewhat overshadowed Jesus—the Blessed Mother could, after all, command the Son to do as she wished. Protestants denounced wholesale the cult of the Virgin, believing the only way a mortal woman could compel God Incarnate was by channelling the Devil’s capacity for trickery, thus statues of Mary were an improper attempt to divert people from the worship of God to the worship of a human and/or a celebration of one of Satan’s instruments. See: Allison P. Coudert, ‘The Myth of the Improved Status of Protestant Women: The Case of the Witchcraze’, in, Elaine G. Breslaw [ed.] (2000), Witches of the Atlantic World: An Historical Reader and Primary Sourcebook, pp. 318-20.

The fissiparous nature of the Protestant movement is a feature that persists to this day. The so-called Peasants’ War launched by radical Protestants in Germany in 1524-25 as the sects tested out the logic of the new ideas solidified a basic division between Magisterial Protestants like Martin Luther who wanted a top-down Reformation—by capturing the magistrates—and the Radical Protestants who wanted a bottom-up revolution that challenged the whole structure of medieval Europe. Luther’s condemnation of the “peasants” was highly controversial at a time when the radicals were gaining ground. The radical Protestant Anabaptists in Munster in 1534-35, however, inspired such horror that Protestant and Catholic Princes combined to put them down, and the pendulum swung back, empowering Magisterial Protestants who wanted an orderly Revolution. In 1546, the Emperor, acting in collaboration with the Pope, made the first effort to forcibly stamp out Protestantism in Germany, but had drawn back in 1552, agreeing to the “whose realm, his religion” (cuius regio, eius religio) formula.

In England, the very next year, Mary I (r. 1553-58) became Queen, displacing her zealously Protestant brother and ruthlessly trying to restore Catholicism, a persecution that would live long in Protestant memory. Meanwhile, the centre of gravity on the Continent had shifted to France, where the First War of Religion between the Catholic Monarchy and the French Protestant minority broke out in 1562. The official proclamation of the Counter-Reformation in 1563 sharpened the battlelines as France went through eight more rounds of war up to 1598. In the background, a Protestant rebellion that would grind away for eighty years had already begun in the Spanish Netherlands—an important aspect of the story of the Spanish Armada that often gets left out. England had been isolated and menaced after the Pope excommunicated Elizabeth I and incited her overthrow and murder in 1570. Obedient Catholics within England made multiple efforts to comply with the Pope’s order, and abroad a Catholic Crusade was clearly being readied as Spain brought France under its influence. Elizabeth had little choice in extending support to the Dutch Protestants in 1585, but it was a de facto declaration of war, a pretext under which to send the long-planned Armada, and a grievance that kept alive an undeclared Anglo-Spanish war until 1604. Throughout it all, atrocity and counter-atrocity piled up, polemicised and exaggerated, widening the breach and hardening antagonistic identities.

Most of the Anabaptists who survived the Munster experience, for example, fled to America and transformed into a peaceable and industrious community.

The French Huguenots had read their situation accurately as early as 1552, when Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, their great leader whose assassination on the Day of Saint Bartholomew in August 1572 was the signal for the mob rampage against Huguenot civilians, tried to create a refuge in Brazil. Coligny then tried twice more, directing the attempt by Jean Ribault at Charlesfort to found a Huguenot colony in South Carolina in 1562, which had to be abandoned within a year, and the effort of René Goulaine de Laudonnière to set up at Fort Caroline in Florida in 1564, which also only lasted a year because the Spanish destroyed it.

In terms of the practical issues that Anglicans and Puritans fought over—the existence of bishops, vestments and ceremony in church, the liturgy (embodied in England in The Book of Common Prayer)—there was considerable similarity with the Catholic-Protestant conflict on the Continent, and the Puritans saw the issues as the same. Bishops and what would later be called High Church practices were seen by Puritans as corrupt remnants of “popery” that needed to be uprooted.

Keith E. Durso (2007), No Armor for the Back: Baptist Prison Writings, 1600s-1700s, p. 25.

An encapsulation of the difference was given by the first minister of Salem, Francis Higginson. As Higginson set sail in May 1629, he said to the other passengers: “We will not say, as the Separatists were wont to say at their leaving of England, ‘Farewell Babylon, Farewell Rome!’, but we will say, ‘Farewell dear England! Farewell the Church of God in England, and all the Christian friends there!’ We do not go to New England as Separatists from the Church of England, though we cannot but separate from the corruptions in it, but we go to practise the positive part of church reformation, and propagate the gospel in America.”

Kevin Sharpe (1992), The Personal Rule of Charles I, pp. 7-9.

The Personal Rule of Charles I, pp. 301-05.

The Personal Rule of Charles I, pp. 38-45.

Puritan propaganda presenting Charles I as a crypto-Catholic who wanted to impose absolutism on England worked with several points early on, most obviously his Catholic wife and the leeway she was given to practice, and outsize attention was given to the “Continental” aesthetic at Charles’s Court. The King’s Personal Rule and the Laudian reforms—rejecting elements of radical Calvinism, focusing on beauty and uniformity in the liturgy, and reinforcing episcopal authority—were seen as concrete proof of an effort to re-Catholicise England and make it a slave of the Pope.

The Personal Rule of Charles I, p. 745.

Harold Wood (1963), Church Unity Without Uniformity: A Study of Seventeenth-Century English Church Movements and of Richard Baxter’s Proposals for a Comprehensive Church, pp. 68-69.

Among the important Puritan figures who returned to England, there was Hugh Peter, who had run a church in Salem. Peter acted as what we would nowadays call a “propagandist-recruiter”, a radical religious preacher roving the land stirring otherwise apathetic people to violence. Peter maintained a high status throughout the Interregnum—he was, for example, the man who gave the sermon at Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell’s funeral in 1658. Peter was one of the most recognisable rebels to Royalists, a hate figure with few equals, ensuring his doom after the Restoration.

Another example is Sir Henry Vane. Arriving back in England in 1639, after four years in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Vane took a seat in Parliament in 1640 and became a leading presence, helping make war unavoidable, since he reliably backed the most radical and destructive option at every point. Vane was, inter alia, a prime mover in the judicial murder of the King’s favourite, Thomas Wentworth, the Earl of Strafford, in May 1641.

The Puritan disdain for the commercial colonies like Virginia was less because of their wealth than a perception they were idolising money, focusing so intently on its accumulation and the luxuries it brought that they had ceased to make sufficient effort to suppress moral vice: “Mammon, not money per se, was the thing to be avoided”. Money as a reward for upholding true godliness was seen as quite natural by the Puritans. Edward Winslow, soon after disembarking from the Mayflower, said New England was a place “where religion and profit jump together”. See: Emerson W. Baker (2014), A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Trials and the American Experience, p. 47.

A Storm of Witchcraft, pp. 47-48.

David Ross Williams (1987), Wilderness Lost: The Religious Origins of the American Mind, pp. 48-49.

The fundamental division between the Thirteen Colonies and the Mother Country at the time of the rebellion that led to the separation—the thing that made all efforts at de-escalation so difficult since neither could properly comprehend the other—was that three-quarters of the English settlers in America were Nonconformists, while this strata represented a mere tenth of England’s population. See: Andrew Roberts (2021), George III: The Life and Reign of Britain's Most Misunderstood Monarch, p. 237.

It was this fact that led Louis Hartz to argue in The Liberal Tradition in America (1955) that the American Republic was founded as a “fragment” broken off from seventeenth-century England, and the common pattern of humanity is that when the likeminded are surrounded by the likeminded, they become more likeminded still. Puritanism had always been a minority in England, and after 1660 one looked at askance, its time in power written into the national memory as a period of dour tyrants and its ideas associated with chaos and sacrilege. Puritanism’s sharp decline in England, and the interplay of an ideologically diverse population, produced a cultural evolution that made eighteenth-century England a very different place to what it had been at the time of the Civil Wars. By contrast, the homogeneous Puritan communities of America preserved the ideas of the Commonwealth and Protectorate, and lamented their demise. It is impossible not to notice that during their 1775-83 rebellion, the colonists phrased their arguments in terms that could have been lifted from defences of the Good Old Cause written in England a century earlier. And once the Republic was founded, its political culture—in everything from the obsession with the written Constitution (the first of which had been implemented by the Protectorate in 1653) to the societal religiosity and constant fear of Roman Catholicism—has remained a very recognisable product of seventeenth-century Puritanism.

The Navigation Acts encouraged self-sufficiency and domestic revenue by preventing English good being transported on foreign ships; only allowing the colonists to sell tobacco, sugar and other “enumerated goods” to England; and ensuring foreign goods bound for the colonies first passed through England to be taxed.

The American colonists grumbled about the Navigation Acts, but they never became a big issue in the seventeenth century and the first half of the eighteenth because the Acts were never very seriously enforced. England (and subsequently Britain) simply had too small a direct presence in the colonies to stop the smuggling. Britain’s attempt from the mid-1760s onward to rationalise the colonial governments and uphold the laws as written, specifically the Navigation Acts, was experienced by many colonists as an intolerable “new” financial burden, and would cited in the charge sheet against London as the colonists moved towards the 1775 rebellion.

New England’s 1675-78 war was with a tribe that had previously been friendly, but became less so under a new chief, Metacom, known to the English as “King Philip”, hence the name of the war. Raids by Metacom’s war bands into southern New England exploded into full-scale war in June 1675. Metacom was killed in August 1676 by a Christian Native, a symbol of the way the war was won: as much by Natives accepting the Puritan offer of integration into the Colony as battlefield successes. A truce was signed in August 1677 and peace formalised the following spring. See: Daniel R. Mandell (2010), King Philip’s War: Colonial Expansion, Native Resistance, and the End of Indian Sovereignty, pp. 118-19.

Michael G. Hall (1988), The Last American Puritan: The Life of Increase Mather, 1639–1723, pp. 121-22.

Jenny Shaw (2013), Everyday Life in the Early English Caribbean: Irish, Africans, and the Construction of Difference, pp. 28-31.

Tim Harris and Stephen C Taylor [eds.] (2013), The Final Crisis of the Stuart Monarchy: The Revolutions of 1688-91 in their British, Atlantic and European Contexts, p. 215.

Kathryn Gin Lum (2022), Heathen: Religion and Race in American History, pp. 43-44.

In 1771, Jean-Louis de Lolme famously wrote in The Constitution of England (1771) that the British “Parliament can do anything except make a man a woman and a woman a man”. The validity of this quote has been challenged in recent years, but just about remains true. Notably, the quote originates a century earlier, in 1648, with Philip Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, a Puritan rebel who had once been a favourite of Charles I’s (and James I’s before that). The Glorious Revolution in effect imposed the rebels’ understanding of King-in-Parliament three decades after they had apparently been defeated.

“King Billy” is best-remembered in Britain to this day for his victory over the fallen James II in Ireland, specifically the Battle of the Boyne (July 1690). Unsurprisingly, this is most remembered among Protestants in Northern Ireland and among nonconformists on the mainland.

Edward Howland (1877), Annals Of North America V1: Being A Concise Account Of The Important Events In The United States, The British Provinces And Mexico, p. 150.

A Storm of Witchcraft, pp. 65-66.

Marilynne Roach (2002), The Salem Witch Trials: A Day-by-Day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege, pp. 43-44.

Mary Beth Norton (2002), In the Devil's Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692, pp. 103-11.

A Storm of Witchcraft, pp. 64-65.

Marion L. Starkey (1949), The Devil in Massachusetts: A Modern Inquiry into the Salem Witch Trials, p. 7. Available here.

Parris had a slightly unusual background for a minister. Born to Puritans in London in 1653, Parris was moved to Boston, Massachusetts, shortly after the 1660 Restoration. Parris gave up theological studies at Harvard in 1673 and went to Barbados, after his father died, to invest his inheritance in a sugar plantation. A hurricane in 1680 put paid to this enterprise and he began looking for a ministry to provide a steady income. Offered the post in Salem, Parris delayed nearly a year until he accepted and arrived in June 1689, partly because he was playing hard to get as a negotiating tactic for a higher salary, and partly out of genuine hesitancy because of Salem’s reputation for communal strife and its record of defenestrating ministers. See: The Devil in Massachusetts, pp. 7-8.

One of the deposed ministers of Salem was Roger Williams, a fascinating figure in his own right and a historically indicative one. One of the earliest Puritan émigrés, Williams had ministered to Salem, despite being a Separatist, from 1631 to 1635, when he was expelled after being convicted on charges of sedition and heresy. Williams religio-political views included a belief that the land belonged to the Natives, a gross affront to the Puritan conviction that the land was given to them by God to create a New Israel.

Williams went south and in 1638 founded the Rhode Island colony, where he also inaugurated the Baptist sect, which emphasised individuality and choice in a Christian’s relationship to God in ways the Puritans found disturbing. A primary point of contention (as Baptists’ name suggests) was the Baptist insistence on adult baptism, a radical doctrine drawn from the Anabaptists (though Baptists largely deny any connection because of the horror attached to the Anabaptists’ memory.) Another major conflict was over Church-State relations: the Puritans in effect, if not quite in theory, combined them; the Baptists demanded total separation.

Soon, however, Williams declared himself free of any affiliation—he held with no “organised religion”, as we would now say—and became a “Seeker”. In this, Williams was an early mover in the trend now so visible of Protestants pushing the inherent features of their creed—individualism, belief as a personal choice, desacralising the public realm—to the logical terminus of removing God from the picture altogether.

As an aside, Williams’ replacement in Salem was none other than Hugh Peter, the Puritan returnee to England in the 1640s who played such an important role in instigating rebellion, ensuring he found himself among the unforgiveables excluded from the King’s mercy after the Restoration. And it was one of Peter’s former parishioners in Salem, Thomas Venner, who led the uprising in London in January 1661 that represented the last gasp of the Commonwealth. Venner’s pitiful band was mostly comprised of his own Fifth Monarchy Men, with some Baptists and Quakers joining them.

See: A Storm of Witchcraft, pp. 46, 214-15.

The Devil in Massachusetts, pp. 7-8.

A Storm of Witchcraft, pp. 66-68.

Barbados is the most important comparator to Massachusetts Bay for understanding the relationship of these early English colonies to the London metropole because it was settled by a different demographic. The planters in Barbados were Royalists. They faced a different existential threat (the Spanish). After the war against the king, they resisted the Atlantic mercantile policies of the Cromwellian state, set in place by the John Fowke-Maurice Thompson clique, that invited the wars with the Dutch. We should talk about it in a podcast sometime!